Biggles’ Last Flight: the flying career of Captain WE Johns

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Biggles’ Last Flight: the flying career of Captain WE Johns

This piece originally appeared in the 100th edition of the WFA's landmark print journal 'Stand To!' The author has enhanced this digital version to include links and more photographs.

To read back copies of Stand To! online, members will need to go to the Login page

Biggles, as many readers will know, was a fictional character created by William Earl Johns (who wrote as ‘Captain’ WE Johns) and was based on Johns’ service with the RFC and RAF in the First World War. Although currently out of fashion, these stories were – in the 1950s and 60s – very popular. Surprisingly, the very first Biggles stories were not intended for children, but for an adult readership. When these early books were reprinted in the 1950s some details were changed to accommodate the younger readership Johns had acquired, for instance a prize of a case of whisky in the original of “The Balloonatics” was changed to a case of lemonade.

The first Biggles story “The White Fokker” was published in the magazine Popular Flying in 1932; a number of these stories were collected as The Camels are Coming, which was first published later that same year. Johns continued to write about Biggles’ service in the RFC/RAF during the First World War until 1939. In this period he produced 63 RFC/RAF short stories plus two full length Biggles books (numbers vary according to different sources - Johns was a blatant self-plagiarist, and recycled many of his stories in later years). Whilst other non-RFC/RAF ‘Biggles’ books were produced in this period, these are few in number.

The cover of the first Biggles book The Camels are Coming. It was first published by John Hamilton Ltd in September 1932, priced 7/2d. Image courtesy of www.biggles.info

Although the character of Biggles was fictional, Johns admitted that he was based on a number of individuals with whom he had served in the war. In the foreword of The Camels are Coming, Johns wrote that Biggles was “a fictitious character yet he could have been found in any mess during those great days of 1917 and 1918.”

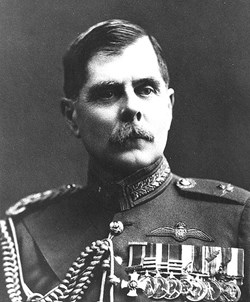

One of the contenders for the source of the Biggles character was Arthur Bigsworth who had gone to sea with the Royal Navy in 1901 at the age of 16 and later trained as a pilot. In May 1915 he became the first airman to attack a Zeppelin at night. Three months later he took on a submarine (according to German records the U-boat did not sink despite some sources saying it did). The citation for the DSO he was awarded for the attack on the submarine read: "Squadron-Commander Bigsworth was under heavy fire from the shore batteries and from the submarine whilst manoeuvring for position.

Arthur Bigsworth of the Royal Naval Air Service. Was he the basis of Biggles? Image courtesy of www.rafweb.org

Nevertheless, displaying great coolness, he descended to 500 feet, and after several attempts was able to get a good line for dropping the bombs with full effect." Johns later used the Zeppelin and submarine incidents in two of his Biggles books.

Despite his own relatively short period spent on a front line squadron, Johns was able to use the anecdotes that he had heard into the foreword of some of his books.

The third Biggles book, and the second of the First World War books Biggles of the Camel Squadron (1934) contained thirteen short stories. Images courtesy of www.biggles.info

The Rescue Flight (1939) was one of only two full length Biggles books set on the western front in the Great War. Image courtesy of www.biggles.info

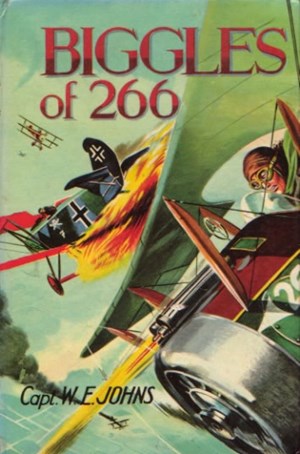

Biggles of 266 (1956) is almost identical in content to Biggles in France (1935). Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Johns’ real anecdotes in Biggles

Johns, in his foreword to The Camels are Coming sets the scene by telling some anecdotes related to the RFC and RAF. He tells, for example about Lothar von Richthofen, the brother of Manfred, the Red Baron, who “shot down over 40 British machines” but was killed “in a simple cross country flight after the war”. He also refers to “Captain ‘Jock’ McKay of my squadron [who] survived three years of air warfare, only to be killed by archie [anti aircraft fire] an hour before the Armistice was signed”. Captain Donald Mackay is the officer Johns refers to, he was injured on 10 November by anti-aircraft fire during an attack on railway sidings; his observer, 2/Lt Harry Gompertz managing to land the machine. Mackay succumbed to his wounds the following day. He is buried at, Jœuf some 40 miles north of Nancy.

Captain Mackay's headstone in Joeuf Communal Cemetery

He also relates “Gordon … made a good landing, but bumped on an old road that ran across the aerodrome, turned turtle and broke his neck”. The Canadian 2/Lt Ralph Gordon was killed when returning from a raid on Kaiserslauten on 25 September 1918 and is buried at Charmes Military Cemetery, 25 miles south of Nancy. His observer, 2/Lt S Burbidge survived the crash.

Charmes Military Cemetery. Image courtesy of the CWGC

In the foreword to Biggles of 266 Johns tells the story of the American pilot Frank Luke “the champion balloon buster” (a pilot who specialised in attacking enemy observation balloons) who was killed after landing his aircraft in order to get a drink of water at a stream. It seems that Johns’ version of the story is inaccurate, Luke had in fact been injured and had landed as a result of the injury – although the story of him drinking from the stream may have come from French civilians. Luke is now buried at the Meuse-Argonne American Cemetery..

Above left: Frank Luke. Image courtesy of Airforce-Magazine.com

Above right: 'Last Kill of the Day' by Ivan Berryman / Cranston Fine Arts

Another anecdote Captain Johns tells is that of a “Colonel Strange” who fell out of his machine whilst it was upside down … “But hanging on to his gun he managed to climb back, right the machine and fly home”. This story is confirmed by the Keep Military Museum’s article on Louis Strange.

On 10 May 1915 there occurred another of those Boys' Own feats with which Louis Strange is associated. At an altitude of 8,500 feet above Menin he was pursuing, in one of the new Martinsyde S1 single-seater scouts, an Aviatik 'belonging to von Leutzer's Squadron from Lille Aerodrome'. Trying to change a used ammunition drum for his Lewis gun, he found it was cross-threaded. Sterner measures were called for and, standing on his seat in the cockpit, he gripped the control column with his knees and tried again. Disaster struck: the aircraft stalled, flipped into a spin and Strange found himself hanging upside down, gripping the useless drum and hoping desperately that he hadn't managed to loosen the thread. 'I kept on kicking upwards behind me until at last I got one foot and then the other hooked inside the cockpit. Somehow I got the stick between my legs again, and jammed on full aileron and elevator; I do not know exactly what happened then, but the trick was done. The machine came over the right way up, and I fell off the top plane and into my seat with a bump.' Although his frantic kicking had smashed all the instruments, he managed to return to base ... The Germans reported Strange as having been shot down but were disappointed not to find any confirmatory wreckage.

Above: Captain (as he was at the time) Louis Strange. Image © and courtesy of the Imperial War Museum

Strange was “criticised by his CO for ‘causing unnecessary damage’ to his instrument panel and seat in his efforts to regain the cockpit.” [‘Aces High’, Alan Clark, Fontana, London 1973, page 34-35]

Another identifiable casualty is Lt Alfred Edward Amey “who fought his first and last fight beside me [and] had not even unpacked his kit.” This brief statement is somewhat inaccurate but bears further explanation; it also knits into the last of the stories in The Camels are Coming called “The Last Show” which may be based on Johns’ own experiences, in this story Biggles is shot down and captured on the last day of the war.

Johns' early war

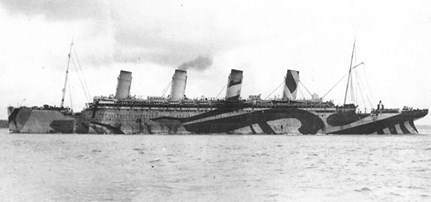

A pre-war territorial in the Norfolk Yeomanry, William Johns was, in 1915, posted to Gallipoli, and sailed on HMT Olympic (a sister ship to the Titanic). The regiment landed at ANZAC cove on 10 October 1915.

HMT Olympic in ‘dazzle’ camouflage. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

The regiment was withdrawn to Alexandria, Egypt, in December to defend the Suez Canal. Johns was trained as a machine gunner and transferred to the Machine Gun Corps in September 1916 before being sent to Salonika where he contracted Malaria. It was while he was in hospital in Salonika that he decided to apply to join the Royal Flying Corps and was accepted, gaining a temporary commission in September 1917.

2/Lt WE Johns. Image courtesy of the Twickenham Museum

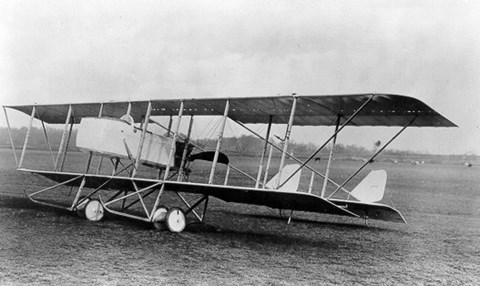

Johns was sent back to the UK to learn the basics of flight at No 1 School of Aeronautics at Reading, before learning to fly at the nearby aerodrome at Coley Park, where he trained in a Maurice Farman Shorthorn.

A Maurice Farman Shorthorn. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

In January 1918 Johns was posted to the No. 25 Training Squadron (Johns was based at the school’s overspill facility at Narborough some 20 miles from the main base at Thetford) as a flying instructor – this was no sinecure as the attrition rate in flying schools was exceptionally high, and it is understood that Johns (or his trainee pilots) wrote off three aircraft in as many days. He described the death in a flying accident of his best friend at the time, Arch Farmer, who died when the RE8 he was flying suffered a mid-air structural failure. Despite not having a parachute, Farmer jumped out of the falling aircraft.

Johns pictured in a flying suit whilst an instructor. He is standing in front of an RE8. Courtesy of www.lowestoftjournal.co.uk

In April 1918 Johns was posted to Marske by the Sea on the Yorkshire coast, the commander of the station being nicknamed Gimlet, a name Johns was to use in another series of books. Marske was the home of No 2 School of Aerial Fighting (a unit where pilots learned the art of aerial combat).

Aircraft hangers at Marske by the Sea. These are almost certainly original buildings dating from the First World War. Image courtesy of Paul Francis / Wikipedia

Johns’ posting to 55 Squadron, RAF

After being ordered to proceed overseas on 20 July 1918, Johns reported to the Hotel Cecil (the RAF Headquarters in London) and from there was instructed to proceed to Lympne in Kent.

The Hotel Cecil in London

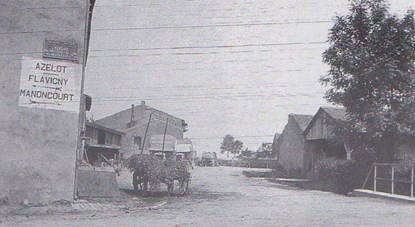

Johns' route from Lympne to Azelot from Lympne to Azelot was one he told in a number of articles in the 1930’s. Using google mapping, Johns' route from Lympne to Azelot can be tracked.

After waiting at Lympne for three days, he decided to proceed to France under his own steam and hitched a lift in a Handley Page O/400 bomber which took him as far as Marquise.

A Handley Page O/400 bomber. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Arriving at Marquise he needed to get to the RAF base at St Omer, but was only able to get a lift to the distant Le Bourget, near Paris. Hitching another lift to a place he hoped was near St Omer called Courban, Johns was to be lucky to escape with his life; approaching Courban, (which was later home to the US 840th Aero Squadron) the pilot crashed, destroying the plane and killing himself. Johns escaped unhurt. Undeterred, he again hitched a lift, this time to Xaffévillers and again was involved in an accident, when the pilot crashed whilst landing. Unhurt, but with his kit lost, Johns was told that the nearby 55 Squadron was in need of pilots. Johns therefore agreed to be taken (by road) to the squadron’s aerodrome at the nearby village of Azelot, which was about eight miles south of Nancy.

Azelot Village, near Nancy - then

Azelot Village, near Nancy - now

Arriving without his kit or any paperwork, Johns was gladly accepted as a replacement for the losses the squadron had suffered on 20 July, when four pilots (Young, Butler, Baker and Pollock) had been killed.

The commanding officer was Major Alec Gray and the squadron’s flight commanders were Capt DRG Mackay DFC (mentioned above), Capt BJ Silly MC, Capt F Williams MC, and Capt JR Bell. Johns operated from the airfield just north east of the village which 55 Squadron (flying DH4s) shared with 99 and 104 Squadrons (which flew DH9s). He later described Azelot and the airfield:

A white dusty road, with little mirabelle trees rambling along the sides... fat, shuffling figures in great clumsy boots... the smell of sheepskin... engines idling, tickeratock, tickeratock, like reapers hurrying in a cornfield...

[Cross & Cockade, vol. 24, no. 4, 1993]

There are just four first World War Graves at the Azelot Communal Cemetery, being members of the Indian Labour Corps who died in early 1918.

The DH4 that Johns was about to fly had been nicknamed ‘The Flaming Coffin’ due to aircraft’s propensity to catch fire (the main fuel tank was situated between the pilot and the observer). Despite this, the DH4 was highly advanced for its time. Johns stated that he thought it “one of the finest machines that ever went to France”.

A computer generated image of a pair of DH4s taking off. The markings are authentic to 55 Squadron’s ‘B’ flight. This and similar images (below) are courtesy of www.riseofflight.com

Johns continued his opinion of the DH4:

At the time of its introduction, no faster machine flew in France, and it was not until 1918 that the enemy produced fighters which surpassed it in speed and climb… It was one of the few [bombers] that dared operate on long distance shows without an escort, and its manoeuvrability was on a par with many single seat fighters of the period.

[‘The Day’s Work’, Wings: A Book of Flying Adventures, 1931 (By Jove, Biggles, page 53)].

The three squadrons at Azelot were part of Maj-Gen Hugh Trenchard's Independent Force, RAF.

Trenchard was appointed GOC Independent Force, RAF on 15 June 1918 with his headquarters in Nancy. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

The Independent Force, RAF was an early attempt at a strategic bombing campaign by units of the (now merged) RFC and RNAS. The force was made up of both day and night bombing squadrons and was based in the Metz-Nancy region, well to the south of the British sector of the Western Front. Its main targets were strategically important railway and industrial centres on the Rhine between Strasbourg in the south and Koblenz in the north. These missions were sometimes as far as 100 miles distant. The attacks were made on the German cities of Frankfurt, Mannheim, Cologne, Coblenz, Duren and Mainz. These bombing raids were highly dangerous and subject to constant attack by the German air force.

Records of the time are incomplete and it is possible that he took part in a raid as soon as 31 July. Other records suggest Johns’ first mission was on 2 September. In later years Johns described some of the raids he took part in, occasionally giving incorrect dates, and later adding extra information. All of this prevents a totally accurate picture of Johns’ service to be provided. Nevertheless, his knack of telling highly engaging and amusing anecdotes of this period enabled his readers to gain a superb flavour of what it was like to be in aerial combat in the First World War.

The bombing raids of 55 Squadron in summer 1918

55 Squadron DH4s on a mission. Image courtesy of www.riseofflight.com

Johns described his first reaction to aerial warfare:

The first dog fight I was ever in…we were sailing along all merry and bright, and the next minute the air was full of machines, darting all over the place…I looked around nervously at my gunner but he was an old hand and merely gave me a pitying glance…Then he sent a stream of tracers in the direction of the rapidly approaching scouts to let them know he was ready for them… I didn’t see where they came from or where they went. I didn’t see where my formation went either. By the time I had grasped the fact that the fight had started and was looking to see who the dickens was perforating my plane, the show was all over. Two machines lay smoking on the ground and everybody else had disappeared. Whilst I was considering what the dickens I should do I suddenly discovered that I was flying back in formation again! The fellows had come back to me pick me up and formed up around me…The leader gave the signal for the bombs to be dropped, and we turned for home. I knew I should get it in the neck when we got back for behaving so foolishly – and I did.

[Passage combined from pieces in The Modern Boy, 5 December 1931 and ‘Adventures in the Air’ The Modern Boy’s Annual 1934 (By Jove, Biggles, page 55)]

He was to be involved in a number of these raids, one of which proved to be very costly: “We had a bad show on August 16, losing Campbell, Fox, Brownhill, Madge, McIntyre and Bracher …. Roberts was wounded but managed to get down”.

[Popular Flying, May 1935 (By Jove, Biggles, page 57)]

This was the result of a bombing mission on Darmstadt. During August alone, 55 Squadron lost 15 aircrew killed plus five wounded and five missing.

A number of incidents at Azelot may have been the basis for some of Johns’ later Biggles stories. For instance, in Popular Flying May 1935, Johns described the British aerodrome being the target of a German bombing raid. This seems to have taken place on 31 August when four casualties (Sgt GE Nye, Sgt H H Wilson, Sgt JH Lowe, Chief Mechanic R Dawson) were sustained. The raid on the airfield is the basis to the Biggles short story “The Battle of Flowers” which was first published in Popular Flying, in October 1932. In this story a German bomber destroys one of the pilot’s flower beds. Another incident at Azelot involved a German pilot becoming lost and attempted a landing on the aerodrome; realising his mistake he tried to escape but was shot at and forced to land. This seems to be the basis for “The Zone Call” in The Camels are Coming.

Johns described another raid – this time on Stuttgart – in a piece which was originally published in Twenty Years After:

The enemy machines begin to take more definite shape as we draw nearer and it is presently possible to make out the shark like fuselages of the Albatrosses and Pfalz, as well as a few Fokker triplanes. Five minutes later a line of enemy fighters, painted in yellow and blue stripes, come down with a roar and a rush. We know them well. They’re the crowd sent down from Metz. In an instant the air is filled with the staccato of machine guns, as if a nest of rattlesnakes has been disturbed – as indeed they have…. Tracer bullets criss-cross lines across the clear blue sky, ours are white – their’s are blackish – and you can smell them as you go through them.

Albatros D.Va from 1918. Image courtesy of Wikipedia

Pfalz D.III. This type was obsolescent by 1918. Image courtesy of Wikipedia

Fokker Triplane. Image courtesy of Wikipedia

After dropping their bombs, the British formation is attacked on the homeward flight. Johns continues his account:

….the real fireworks are about to begin….Taca-taca-taca-tac. I look across at the machine beside me. The gunner is crouched over his Lewises. Tracers pour from the twin barrels as three machines attack him together, all from different angles. My heart lurches as a burst rips through my own machine, and the altimeter simply disappears in a cloud of splintered glass.

DH4s of 57 Squadron fight off Albatross DVs of Jasta 18. This encounter took place in October 1917. Image courtesy and copyright of www.russellsmithart.com

I look over my shoulder to see what is happening. Cox is firing downwards, first to one side, then to the other. So that is the game! I gently press my right foot on the rudder bar, just enough to swing the tail aside, and disclose a blue-nosed Albatross that has crept up beneath my elevators. He is in the open now and Cox plasters him at point blank range. He jerks up, stalls slowly over onto his back, and falls like a stricken bird.

[Twenty Years After edited by Major General Ernest Swinton. George Newnes Limited, London, 1938]

On 2 September 55 Squadron attacked Buhl aerodrome twice on the same day. Johns flew with his usual observer/gunner 2/Lt FN Coxhill. (Johns mis-remembered him as 'Cox' in the above account).

After some poor weather which prevented flying, another raid took place on 14 September, the target being the railways lines at Ehrang which at this place went through a bottleneck. The aim of the raid was to throttle off supplies to the front. Johns was flying with a new observer as Coxhill had gone ‘sick’ with toothache. The replacement observer/gunner was 2/Lt Amey.

Johns and Amey were in the air again the following day, 15 September; the target for this raid was the Daimler works at Stuttgart, nearly 100 miles behind the lines. Coxhill, having recovered from his toothache was assigned to a different pilot. Johns was flying with Amey for a second time. Setting off at 7.20am, the formation was not troubled by enemy aircraft, although three of the original twelve aircraft had to turn back before crossing the lines due to mechanical problems.

DH4s from 55 Squadron

The raid was not a success, the factory was undamaged, but nearby houses were hit by the bombs, causing some civilian deaths.

That night, after a party in a hotel in Nancy, Johns found himself stranded when a fellow officer who had offered him a lift back to base failed to turn up. This was a potential embarrassment for Johns as he was due to fly another mission the following morning. Using his initiative, Johns managed to obtain a lift in an American ambulance, however, they got lost and found themselves at a remote country house. One of the occupants of the house was a young girl with the ‘face of an angel’. The girl became the basis of Marie Janis in the Biggles short story “Affaire De Coeur” (a story within The Camels are Coming) and she again featured in one of Johns’ last books Biggles Looks Back (1965).

After obtaining directions to Azelot, Johns returned to his base at 3.30am on Monday 16 September. Although married with a wife and child back in the UK, Johns had every intention of returning to the house. Nine hours later at 12.20 pm, and no doubt with the young girl on his mind, Johns took off again for another mission. The squadron had been ordered to attack the Lanz Aero works at Mannheim. With a flight time to the target of just over two hours, they were, as ever, in danger of being intercepted.

The Lanz works. Image courtesy of Lanz-Bulldog.

Johns’ last flight

55 Squadron took off. Flying in two formations, each of six aeroplanes, Johns (piloting a DH4, serial number F5712) was part of Captain ‘Jock’ Mackay’s formation. The leader of the other formation had difficulty with his engine and as a result the six aircraft in the second formation failed to rendezvous with Mackay’s group and returned to base.

Despite this, the six aeroplanes in Mackay’s flight pressed on, climbing away from Azelot and crossed the front line near Raon-l'Étape and headed towards Saverne. It was at about this point that Johns' DH4 seems to have been hit by ‘archie’.

Johns recounted the story in a number of articles in the 1930’s: ‘Shot Down from 20,000 Feet!’ The Modern Boy 2 February 1931; ‘My Most Thrilling Flight’ Popular Flying June 1932; ‘Why I am Still Alive!’ Answers, 11 August 1934; and finally in Popular Flying June 1936. [By Jove, Biggles, page 87.]

I was watching a string of what appeared to be gaudy butterflies crawling along the ground; now and then the sun flashed on their wings. It was a full squadron of Fokker DVIIs trailing us and climbing fast. There was a bit of ‘archie’ about, nothing to worry us, but the odd chance came off. There was a terrific explosion almost in my face, and a blast of air and smoke nearly turned my machine over. I tried the controls anxiously and all seemed well but a stink of petrol filled my nostrils and I glanced down; my cockpit was swimming with the stuff.

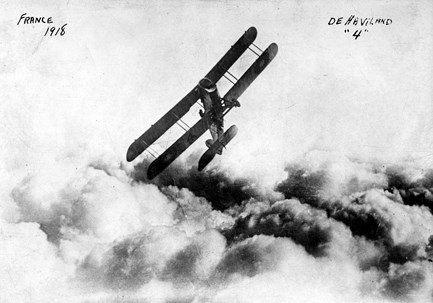

Biplane above the clouds. Handwritten on photograph front: "France, 1918, De Haviland '4

Johns’ fuel tank had been holed. Petrol flooded through the DH4, and Amey bravely (or possibly foolishly) fired a green Very light to signal that they were having to turn back. Thankfully this did not set the aircraft on fire, and Johns, jettisoning his bomb load (which would have been either a single 230lb bomb or two 112 lb bombs) pulled back on the control column of his damaged machine in an attempt to out-climb the fighters. Below him were seven Fokker DVIIs – it was possible that his aircraft may be able to make the front lines, where at least he would able to come down in friendly territory.

A modern day replica of Fokker D.VII. Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

With a petrol vapour trailing from his stricken machine, Johns was in serious danger of facing the death that all pilots fear the most – being caught in a burning aeroplane without a parachute.

A depiction of DH4 of No 25 Squadron (note the crescent marking on the fuselage) being attacked by a Fokker D.VII. Although an excellent painting, an explanation is needed here: The D.H.4 is showing No 25 Sqn’s crescent marking, which was discontinued in March 1918, being attacked by a Fokker D.VII of Jasta 15 (red nose and blue fuselage), a type that came into front line service after April 1918. More particularly, in the DH4 in question, A7442, had served in No 57 Sqn before going to No 25 Sqn on 7 August 1917. The machine was damaged in a rough landing on 24 October 1917 at Boisdinghem aerodrome during a practice flight. It was removed to a Repair Park and was re-built as F5830 in June 1918 and it returned to No 25 Sqn; it force landed on a road near Hangard on 7 October 1918. The (different) crew members survived both of these incidents.

Johns describes what happened next:

The leader came in with rush and I touched the rudder-bar to let his tracer go by. A bunch of them came up under my elevators and I kicked out my foot, slewing Amey round without losing height, to bring his guns to bear. The Fokkers came right in and I give them credit for facing Amey’s music. One turned over, a second spun out of it, but another came right in to point-blank range; Amey raked him fore and aft without stopping him. Others came down on us from above.

Inevitably, despite his advantage in height, the enemy planes overhauled his damaged bomber. Amey fired at the Germans using his Lewis guns, but the Germans returned fire and Amey was hit, falling to the bottom of the cockpit. Now without a gunner to fend off the Germans, Johns’ fate was sealed. Johns continues the account:

Sick with fright and fury, I looked around for help, but from horizon to horizon stretched the unbroken blue of a summer sky. Bullets were striking the machine all the time like whip-lashes, so I put her in a steep bank and held her there while I considered the position. For perhaps five minutes we tore round and round, the enemy getting in a burst now and then and me ‘browning’ the whole bunch of them, but I could not go on indefinitely. My ammunition was running low and I was still over forty miles from home…. Things looked bad. To try to make forty miles against ten or a dozen enemy machines (several others were joining in the fun) was going to be difficult. In fact, I strongly suspected that my time had come.

[Popular Flying June 1936 via By Jove, Biggles, page 87]

Johns was also hit by a bullet and his instrument panel was destroyed. His only hope was to try to land the DH4 before it burst into flames or was destroyed by the circling Germans. Johns put the machine into a spin to lose height and to try to shake off the Fokkers. Pulling out of the spin at 8,000 feet, Johns was no doubt devastated to discover a Fokker had stuck with him – this German proceeded to put a burst of machine gun bullets into Johns’ engine. Using all his skills, Johns somehow maintained control and the DH4 remained in the air.

Passing from a steep bank, Johns—formerly an instructor at No. 2 School of Air Fighting, Mart—stunted the heavy Four like a scout until he was down to about 8000 ft. When he pulled out a striped Fokker was clinging to his tail, and with that revelation came a Maxim burst through the new 375 hp RR Eagle VIII —probably the first engine of its type to fall on Germany. Power vanished, and Johns spent the next minute in tugging up the gashed nose. The machine's final swoop carried it straight for a peasant and his horse, who separated abruptly. Next in line was a clump of trees ...

[Extract from The first of Many: The Story of the Independent Air Force, RAF by Alan Morris, Jarrolds, London, 1968]

A computer generated image of a Fokker D VII. The markings are fictional but indicate the sometimes bright colour schemes adopted. Image courtesy of www.riseofflight.com

As he approached the ground, a line of trees came into view. Unable to avoid them, Johns crashed into them and was thrown against the front of his cockpit, causing him to burst his nose on the butt of his Vickers Machine Gun. He had – against all the odds – managed to bring his machine down. Bleeding from various injuries, Johns came round to find himself faced with German soldiers who proceeded to punch him.

Using 'Google Maps', the line of Johns’ final flight can be roughly tracked.

Leutnant Georg Weiner, who was in command of Jasta 3 claimed he had downed an aircraft at 1.30pm on 16 September near Alteckendorf. It is believed that this was Johns’ machine. Weiner was to end the war with a total of nine victims – which was enough for him to be classified as an “ace”.

Leutnant Georg Weiner. Image courtesy of CollectiveHistory.com

Whilst Johns had been attempting to dive for the lines, he had seen in the distance a lone British aircraft which had been brought down in flames. It is possible that this was a DH9A, crewed by Sergeant A Haigh and Sergeant J West of 110 Squadron – which was also raiding Mannheim at about the same time as Johns’ 55 Squadron.

Taken to the nearby village of Ettendorf (which is north of, and adjacent to Alteckendorf) along with the body of the dead Amey, Johns was taken to the village school and informed he would be shot.

Ettendorf School in 2013

To reinforce this, his captors put him through a court-martial. However, despite the threats, he was sent off to a Prisoner of War Camp for the remainder of the war.

The remaining five DH4s of 55 Squadron continued their flight to Mannheim and delivered the attack on Lanz Aero works. Arriving over the target at 2.35pm, from a height of 16,000 feet they dropped three 230lb and four 112 lb bombs, this caused very little damage. Although enemy aircraft were spotted on the return journey, the formation was not engaged.

A (U.S.-built) DH-4 releasing bombs. The USAS chose the British DH4 for mass production. It was the only US-built aeroplane to see service on the Western Front. Image courtesy of earlyaeroplanes.com

Captain WE Johns after World War 1

But for his flying ability, and a large slice of luck, it is certain that Johns would have been killed and have been buried alongside the unfortunate Lt AE Amey. Johns remained in the RAF after the war, and became editor of a number of magazines. His wartime experiences in France, although brief, gave him suitable material to create ‘Biggles’ – a character who became an icon for many. Johns’ ability to ‘paint a picture’ is an impressive legacy, and is exemplified by the following from Biggles Learns to Fly (1935):

Biggles looked over the side and caught his breath sharply as he found himself gazing into a hole in the clouds, a vast cavity that would have been impossible to imagine. It reminded him vaguely of the crater of a volcano of incredible proportions. Straight down for a sheer eight thousand feet the walls of opaque mist dropped, turning from yellow to brown, brown to mauve, and mauve to indigo at the basin-like depression in the remote bottom. The precipitous sides looked so solid that it seemed as if a man might try to climb down them, or rest on one of the shelves that jutted out at intervals…

William Johns died on 21 June 1968 whilst working on Biggles Does some Homework. It may have been that this was going to be the last Biggles book as the storyline for this centred around Biggles contemplating retirement.

William Johns. Image courtesy of www.lowestoftjournal.co.uk

55 Squadron

When the Independent Force was formed in June 1918 to carry out strategic bombing of targets in Germany, 55 Squadron developed tactics of flying in wedge-shaped formations and bombing on the leader's command.

DH4s flying in a wedge-shaped formation.These are post-war US-built DH-4Ms, which had metal framed fuselages, 400hp Liberty engines and DH9-style rearranged cockpits; quite different to the DH4s of the RAF.

The combined defensive fire of the squadron flying in close formation deterred attacks by all but the most determined German fighter pilots. Although suffering heavy losses, the squadron continued in operation and was the only day bombing squadron in the Independent Force which did not have to temporarily stand down owing to aircrew losses. Although 55 Squadron was just one part of the Independent Force, RAF (which at its maximum only consisted of nine squadrons), and the weight of bombs delivered by later standards was tiny, the attacks made by 55 and other squadrons were the forerunners of the strategic bombing attacks of Second World War.

Below is the list of fatalities of 55 Squadron from July 1918 to the Armistice, highlighted is Johns’ observer/gunner, 2/Lt Amey.

David Tattersfield

|

Surname |

First Name / initial |

Age |

Date of Death |

Rank |

Cemetery |

Grave |

|

CURRIE |

W H |

|

16/07/1918 |

2/Lt |

Charmes Military Cemetery |

I. A. 10. |

|

WHITELOCK |

CHARLES RAILTON |

20 |

16/07/1918 |

Lt |

Charmes Military Cemetery |

I. A. 9. |

|

BAKER |

WILLIAM EDWARD |

|

20/07/1918 |

Sjt |

Niederzwehren Cemetery |

I. H. 2. |

|

BUTLER |

REGINALD ARTHUR |

24 |

20/07/1918 |

Lt |

Niederzwehren Cemetery |

I. H. 3. |

|

POLLOCK |

J F |

|

20/07/1918 |

2/Lt |

Charmes Military Cemetery |

I. A. 11. |

|

YOUNG |

CHRISTOPHER |

27 |

20/07/1918 |

Lt |

Niederzwehren Cemetery |

I.A. 1. |

|

STEWART |

R |

20 |

12/08/1918 |

2/Lt |

Charmes Military Cemetery |

I. A. 13. |

|

LEWIS |

S E |

|

13/08/1918 |

Sjt |

Charmes Military Cemetery |

I. E. 13. |

|

BRACHER |

HERBERT HECTOR |

18 |

16/08/1918 |

2/Lt |

Sarralbe Military Cemetery |

C. 12. |

|

McINTYRE |

JAMES BENNETT |

24 |

16/08/1918 |

Lt |

Sarralbe Military Cemetery |

C.11 |

|

BROWNHILL |

ERNEST ALBERT |

25 |

16/08/1918 |

2/Lt |

Niederzwehren Cemetery |

II. A.1. |

|

MADGE |

WILLIAM THOMAS |

19 |

16/08/1918 |

2/Lt |

Niederzwehren Cemetery |

II.A.2 |

|

FOX |

JOHN ROBERT |

20 |

16/08/1918 |

2/Lt |

Ingwiller Communal Cemetery |

|

|

LEE |

J A |

18 |

25/08/1918 |

2/Lt |

Charmes Military Cemetery |

I.A.18. |

|

ALLAN |

ALEXANDER S. |

24 |

27/08/1918 |

Sjt |

Charmes Military Cemetery |

I.A.17. |

|

HICKES |

ROBERT |

19 |

30/08/1918 |

2/Lt |

Latour-en-Woevre Communal Cemetery |

|

|

JONES |

THOMAS ALFRED |

19 |

30/08/1918 |

2/Lt |

Latour-en-Woevre Communal Cemetery |

|

|

LAING |

THOMAS HARRY |

23 |

30/08/1918 |

2/Lt |

Arnaville Churchyard |

|

|

MYRING |

THOMAS F.L. |

19 |

30/08/1918 |

2/Lt |

Arnaville Churchyard |

|

|

QUINTON |

J G |

18 |

30/08/1918 |

2/Lt |

Charmes Military Cemetery |

I. B. 8. |

|

CUNNINGHAM |

P J |

|

30/08/1918 |

2/Lt |

Charmes Military Cemetery |

I. B. 9. |

|

THORP |

CHARLES EVANS |

19 |

30/08/1918 |

2/Lt |

Charmes Military Cemetery |

I. B. 6. |

|

AMEY |

Alfred Edward |

|

16/09/1918 |

2/Lt |

Sarralbe Military Cemetery |

B. 11. |

|

ATTWOOD |

J. T. LESLIE |

22 |

25/09/1918 |

2/Lt |

Charmes Military Cemetery |

I.C.5. |

|

BARBER |

G S |

|

25/09/1918 |

2/Lt |

Charmes Military Cemetery |

I.C.4. |

|

BURNETT |

H R |

|

25/09/1918 |

2/Lt |

Chambieres French National Cemetery, Metz |

403 |

|

ROBINSON |

A J |

21 |

25/09/1918 |

2/Lt |

Chambieres French National Cemetery, Metz |

351 |

|

DUNN |

JAMES BALFOUR |

19 |

25/09/1918 |

2/Lt |

Niederzwehren Cemetery |

IV. N. 1. |

|

ORANGE |

HAROLD STARLING |

18 |

25/09/1918 |

2/Lt |

Niederzwehren Cemetery |

IV. N. 2. |

|

GORDON |

RALPH VYVIAN |

22 |

25/09/1918 |

2/Lt |

Charmes Military Cemetery |

I. B. 19. |

|

REYNOLDS |

CHARLES EDWARD |

22 |

23/10/1918 |

Lt |

Charmes Military Cemetery |

I. C. 19. |

|

FLEISCHER |

DERRIC CECIL |

20 |

03/11/1918 |

2/Lt |

Charmes Military Cemetery |

I. F. 11. |

|

MERCIER |

HERBERT |

20 |

03/11/1918 |

2/Lt |

Charmes Military Cemetery |

I. F. 11. |

|

MACKAY |

DUNCAN R. G. |

23 |

11/11/1918 |

Capt |

Joeuf Communal Cemetery |

|

Bibliography

Clark, Alan Aces High, Fontana, London 1973

Ellis, Peter Berresford and Williams, Piers By Jove, Biggles! The Life of Captain WE Johns, WH Allen & Co PLC, London, 1981

Morris, Alan The first of Many: The Story of the Independent Air Force, RAF, Jarrolds, London, 1968

Rennles, Keith Independent Force: The War Diary of the Daylight Bomber Squadrons of the Independent Air Force , Grub Street, London, 2003

Further Reading

Biggles, the Battle of the Flowers and the RAF in the First World War

Acknowledgements

* My thanks to Gareth Morgan of the Australian Society of World War One Aero Historians who has provided the encouragement for this article and also corrected errors. Any that remain are my responsibility alone.

* Rise of Flight (www.riseofflight.com) for various images.

* Use of extracts from the work of W E Johns by permission of Rogers, Coleridge & White Ltd, the literary agent for the Estate of W E Johns. The agency have advised that there are plans afoot to republish most of the Biggles books either in print or as e-books, as well as plans to introduce Biggles to a new generation of readers.