The Road to Sheik Sa’ad

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Road to Sheik Sa’ad

On the outbreak of war, the 1st Battalion of the Seaforth Highlanders were in India but were ordered to move to France, in the Dehra Dun Brigade, Meerut Division of the Indian Corps, under the command of Lieutenant General Sir James Willcocks.

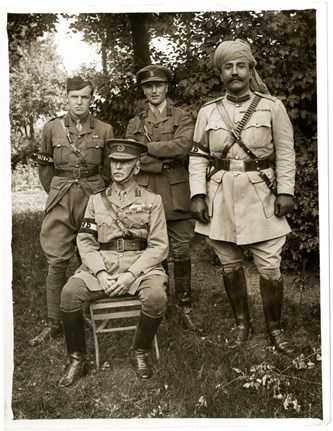

Above: Sir James Willcocks and his personal staff in the garden at his headquarters at Merville, France.

The battalion arrived at Marseilles on 12 October 1914 and within a few days were on the way north. During its time in France, the battalion would spend much of it in the Festubert and Neuve Chapelle area, with the first action of any significance taking place on 20 December 1914 when the Germans attacked, with the 2 Gurkas and 1 Seaforth bearing the brunt of this attack. Willcocks would later write of this:

‘The Seaforths never lose an inch of ground without making the attackers pay a heavy toll, but they were now fighting against great odds, hand grenades, machine guns, and trench mortars, with both their flanks in the air. One company was driven from its trench, but not until fifty per cent of the enemy lay dead in it.’[i]

It would later take part in action at Neuve Chapelle on 10 March 1915 and at La Bassee on 9 May 1915. At Loos, the battalion were in reserve and were not involved in any major action at that time. Nonetheless the War Diary recorded at the end of 1915 that since its arrival in France in October 1914, 15 Officers and 407 men had been killed.

But by November 1915, change was in the air for the battalion as Private White would write to his mother:

‘We are leaving France at an early date, possibly the 13th or 15th of this month. We are sailing from Marseilles and as far as we can learn we are going to either Egypt or India…I’ll try to drop you a postcard as we go on, and I’ll put the name of the town on by the dot method. Don’t send any more parcels until I tell you’[ii]

The War Diary reported that the train left ‘punctually’ at 11.50am.

Above: ‘A halt enroute south’

By 7pm on 25 November, it arrived in Marseilles where the Battalion marched to the docks and embarked on HMT ‘Lake Manitoba’ at 9.15pm. The ship finally sailed from Marseilles to Toulon on 28 November 1915, sailing from Toulon on the following day, ‘destination unknown’ recorded in the Diary. Two days later, St Andrew’s Day was celebrated on board, with Captain Ross recording in his personal diary

‘Day was observed by special dinner at night. Pipes played in the Haggis and gave a selection of tunes during the meal. The pipes were too much for the ship’s doctor’.[iii]

Above: HMT Lake Manitoba at Port Said

The ship anchored in Aden briefly on 16 December 1915, before proceeding to Basra through the Arabian Sea, the Gulf of Oman and the Persian Gulf. By 20 December, Ross records that machine gun practice was being held on deck:

‘Porpoises provided excellent targets for the machine guns. The range was estimated perfectly and the shots were among them at once. There was a regular porpoise panic - some going in one direction- some in another.’[iv]

Orders to be ready to proceed up the Shatt-al-Arab river were received on 24 December but cancelled on 25 December as the ‘Lake Manitoba’ was drawing too much water. Instead, she returned to Kuwait where it was intended that 1Seaforth would transfer to a smaller boat, the ‘Nizam’, an Asiatic Steamship Company’s Passenger Cargo vessel, on 25 December. The Seaforths arrived in Kuwait before the ‘Nizam’ so had to await its arrival in the harbour. Nonetheless, a Christmas Dinner was enjoyed at midday.

By 4.30pm, the ‘Nizam’ left Kuwait. On its journey up the Shatt-al-Arab, it passed three ships which the Turks had sunk to obstruct the river. The ‘Nizam’ later dropped anchor in the river opposite Basra. In the intervening period before the ‘Nizam’ moved, Captain Ross and two officers went ashore to the bazaars of Basra.

For the last stage of the water journey, the 1 Seaforth transferred to ‘Julnar’, a two storied flat bottomed river-boat, with the cookers on one barge fixed to the ‘Julnar’ and the battalion stores on a second barge. Captain Ross described that on each of the barges, which had reed awnings, there were 50 men ‘all ready to land at a moment’s notice in case of any demonstration from hostile Arabs’. On the deck of the ‘Julnar’ there was a very small saloon with some small cabins but as remarked in the War Diary, ‘sanitation and water arrangements not at all good’. The journey upstream was interesting for the men with Captain Ross describing:

‘Today a party of natives seated on the bank took fright at sight of us & fled at top speed, much to the delight of the Jocks – possibly their first sight of a kilt’.[v]

On 29 December 1915, the ‘Julnar’ entered the River Tigris and by 31 December had reached Amara, where the hospital stores on board were unloaded. At 11.35am, the ‘Julnar’ sailed for Ali-al-Garbi, arriving on 1 January 1916, where the battalion pitched camp on the left side of the Tigris - the fighting strength of the battalion being noted as 26 Officers and 887 men. It would form part of the 19 Composite Brigade,in the 7th Indian Division, under the temporary command of Col. Dennys, of the 125 Rifles, along with 125 Rifles, the 28 and 92 Punjabis. Here, the Battalion Diary recorded:

‘transport was issued on Indian scale and scarce at that – only one blanket and a waterproof sheet being carried for each man and Officer kits being limited to 30 lbs.’

In camp, Captain Ross commented that ‘it was rather a squash in each tent for the men’ whilst two officers each shared a smaller tent. But the officer’s mess tent was ‘magnificent and elaborate’ - it had transferred from India to France where it had been warehoused in Paris, from where it was recovered before the battalion moved south to Marseilles.

On 3 January, orders were received for the battalion to move up river on the following day with the objective of reaching Kut to relieve the besieged garrison.. Captain Ross elaborated on the kit arrangements:

‘The men are to carry only their rations, a blanket, spare shirts & socks & sleeping helmet. Officer’s kits for transport are limited to 35lbs. I had great coat, 2 blankets, waterproof coat, canvas bucket & washing materials etcall tied up in a waterproof sheet. The rest of my kit, with the exception of what I had in my pack, all went in my valise & to the boat’.[vi]

Above: ‘A Halt on the march’

Progress over the following two days was hampered largely by transport difficulties and the terrain, which prolonged rain overnight had turned into ‘a ploughed field’, resulting in less than 10 miles being covered each day. Matters were not helped by it being quite chilly at night and the men having only one blanket each. During the frequent halts en-route, blankets were taken out to dry in the sun at every opportunity. On Thursday 6 January 1916, the 1 Seaforth heard the first sounds of gunfire from the opposite side of the river.

On 7 January towards midday, 1 Seaforth were ordered into the attack. Just as they were within sight of the enemy, an order was received to change direction to the left for 1000 yards. Whilst effecting this change, the Seaforths came under heavy fire. The War Diary commented that

‘the action was most disappointing, the only bright feature being the gallantry and rigour of the men in the first stage under a heavy cross fire and their steadiness and grit in digging and holding the line later’.

Ross was more outspoken in his diary –

‘the attack was made when the mirage was at its very worst..12.30…….we had no field artillery at all on our own side of the river until 5 in the evening and no shell of any sort fell on or near the lines we were attacking….but there was nothing to approach the stupidity for us to change direction….’[vii]

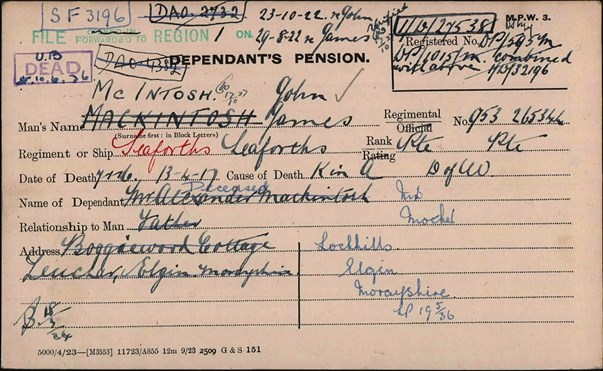

Ross was wounded during the attack. Alongside a number of fellow Officers of whom five were killed or died of wounds. 65 other ranks were killed or died of wounds - amongst these, Private John McIntosh and Corporal James Robb, who had both enlisted pre-war.

Private John McIntosh was born at Rosehaugh, New Spynieon 26 March 1893, the son of Alexander and Jane McIntosh, who later lived at Calcots, Elgin. He had been working as a horseman on a farm when he enlisted in the 1 Seaforth Highlanders at Fort George in 1911.

Corporal James R Robb had served in the regiment for 9 years. He was born in Keith in March 1890, the son of John and Elizabeth Robb.

The family later moved to Elgin where James would lose his older sister, Lizzie, aged 10, in 1898. Within a year, he would lose his mother on 13 September 1898 and then his father on 9 December 1899, all from tuberculosis. Before he enlisted, he had lived with his grandmother but she had also died in 1910.

Both John and James are commemorated on the Basra Memorial.

Above: The Basra Memorial. It was originally built in the port of Basra - this image shows it in the 1930s.

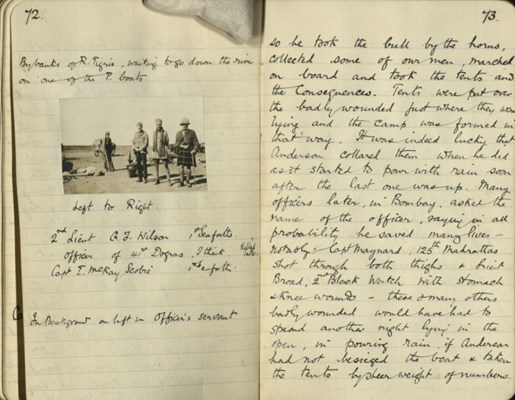

After the action on 7 January, the wounded had a difficult time. Almost all the Battalion stretcher bearers were killed or wounded and many wounded men received further injuries while they were lying in the open or being taken back to the Hospital Camp about 4 miles from the firing line. Bullock carts were used to transport casualties but ‘these jolted the wounded terribly’ according to Ross. Furthermore, Ross described that many wounded had to spend a bitterly cold night in the open and were extremely lucky if they got a blanket. Food and drink were next to impossible to secure and unsurprisingly the morning of 8 January found many of the wounded the worse for wear. Captain Anderson and some men fetched the battalion’s tents from a nearby boat, and although Anderson was told that he could not have them…Ross relates that ‘ he took the tents and the consequences’.

Above: A page from Ross’ diary

Ross was also fulsome in his praise of the medical staff (Captain W. Dawson, the Medical Officer to the Battalion, later received the DSO for his actions in tending to the wounded).

On 12 January, Ross and four other Seaforth officers were taken on board a boat to Amara along with other ranks, finally reaching Basra on 17 January 1916. Of this journey, Ross commented:

‘We took the places of horses which it had brought to the river. There was no attempt to clean the boat at all before we were put on and it & the barges were filthy. I don’t know what our exact numbers were but I should say about 400 – almost all lying down cases. There were no cups, forks, knives etc &very little food and it was a question of hands for eating & old jam tins for drinking purposes…… There was one doctor on board and a few very inexperienced orderlies - consequently careful attention was an impossibility - cleanliness still more impossible as there were no dressings except for the most urgent cases. It rained hard practically the whole journey of 5 days and men were lying in water and when the boat pitched over a little to one side or the other, a regular stream poured between the various men lying down on the decks. Everything got soaking wet. Some of the things which happened on board this boat were too revolting to put down in writing. Other boats of this class were exactly the same& in fact, every boat, taking wounded down the river, defies description’.[viii]

From Basra, Ross would board the ‘Varela’ to Bombay and later spend time in Colaba Hospital in India. He returned to the Battalion later in 1916.

Today in Iraq

The country is obviously still recovering from recent conflicts, but - somewhat surprisingly - the Basra Memorial remains intact, having been moved (under Saddam Hussein) from its original position in the port to a new location some miles west of the city.

Article submitted by Jill Stewart, Hon Secretary, The Western Front Association

Footnotes:

[i]Willcocks ‘With the Indians in France’ (1920)

[ii] Archive File 89-81a, The Queen’s Own Highlanders Collection

[iii] Archive File 00-156, The Queen’s Own Highlanders Collection

[iv]Ibid

[v] Ibid

[vi]Ibid

[vii]Ibid

[viii]Ibid