Chilwell – the VC factory explosion 1 July 1918

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Chilwell – the VC factory explosion 1 July 1918

In 1914 the British armaments industry was primarily geared to supplying the needs of the Royal Navy, export markets, and a small regular army. The Navy’s and Army’s relatively modest armament needs were largely met by state-owned factories and a handful of private firms. But by autumn 1914, it was clear that the essentially static trench warfare of the Western Front required huge numbers of artillery pieces, shells, and explosives.

Initially, to meet this demand, England’s existing factories were expanded, but by spring 1915 the so-called ‘Shell Scandal’ (too few being produced and too many of those that were failed to explode) led to further state control and the creation of the Ministry of Munitions and over 200 National Factories. Lloyd George became the head of the newly formed Ministry of Munitions in May 1915.

Above: David Lloyd George

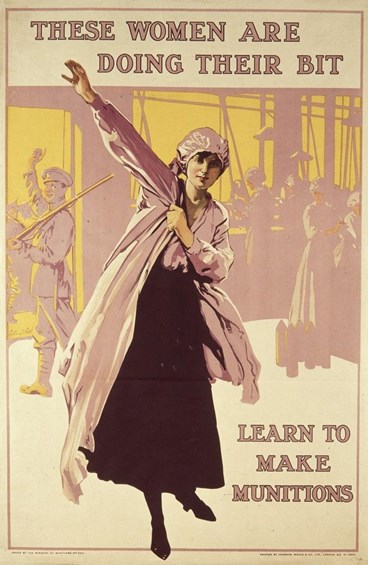

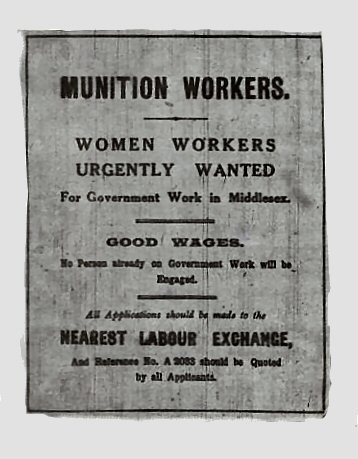

A number of new initiatives were soon introduced to improve production levels. One of these was an appeal for women to register for war service work.

Above: Poster recruiting women into munition work

Thousands of women volunteered as a result, and many of these were soon employed in the growing number of munitions factories across the country. Munitions work was extremely dangerous and the women worked long hours. The TNT (trinitrotoluene) in the munitions turned the women’s skin yellow and they became known as ‘canaries’. Workplace accidents were also a danger as were explosions. There were a number of explosions at munitions factories - at least 108 were killed at Faversham, Kent 2 April 1916 ; on 19 January 1917, 69 workers died in an explosion at Silvertown, East London and on 13 June 1917, 53 workers died in an explosion at Ashton-under-Lyme.

Above: The Venesta factory, which produced wood veneer packing cases for the tea trade, lies in ruins following the detonation of 83 tonnes of TNT at the Brunner Mond's explosives factory in Silvertown, East London, on 19 January 1917. © IWM Q 15364

However, the greatest loss of life in a munitions factory explosion would occur on 1 July 1918 at Chilwell.

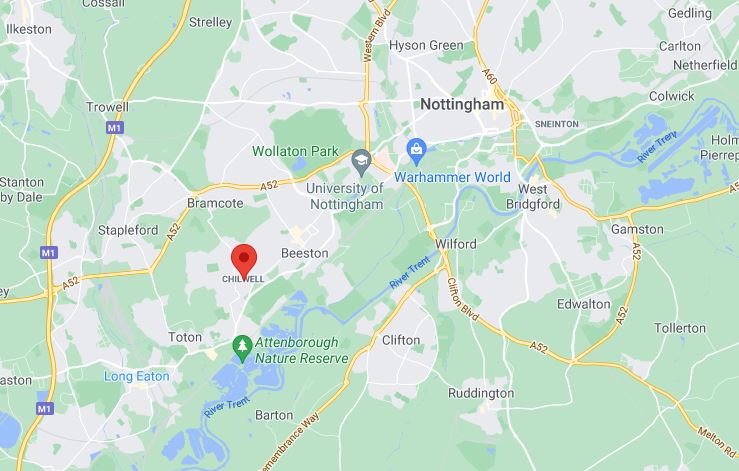

The Factory was located near Nottingham, described in ‘The Chilwell Story’ as

‘practically pure countryside surrounded by a small collection of villages. In these villages, such as Beeston, Attenborough and Long Eaton lived men and women who had traditionally worked in the lace making centre of Nottingham and Derby. The demand for cheap lace had, however, diminished with the war and thus there were large numbers of people in the area seeking employment and plenty of accommodation for others who might have to be brought in’.

The factory owner was Godfrey John Boyle Chetwynd, the 8th Viscount, whose drive and personality played a major part in the development of the factory.

Above: Viscount Chetwynd

As the war progressed, the use of lyddite was precluded as it required imported raw materials. One of the challenges faced in the production of munitions was that TNT was expensive and limited in amount. As demand for high explosive shells grew, it became obvious that the supply of pure TNT would not be adequate – hence the development of Amatol mixtures of TNT and Ammonium Nitrate. The problem was how the shells were filled – and it was in this that Lord Chetwynd was instrumental in developing a new method of shell filling which involved milling and pressing the mixture.

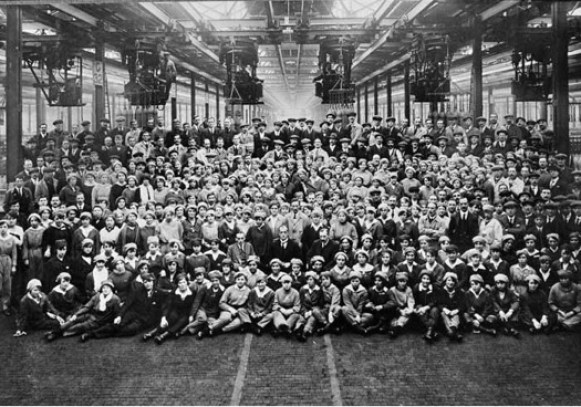

By October 1916, the factory was effectively complete with nearly 6,000 people employed on production – 2,000 of them women.

Above: A woman drives a trolley train across a busy factory floor at the National Filling Factory, Chilwell. The trolley is loaded with shells and is used to transport the shells from one part of the factory to another. Around 21 August, 1917. © IWM Q 30023

Above: Many of Chilwell’s workers were women. Photo - MoD

Life for the workers within the factory gates was hard, with twelve hour shifts and a workload that was continually increasing, with little time for socialising. A number of those employed in the TNT Mill began to suffer from TNT poisoning, with a number of deaths in the early days of the factory. Greater ventilation in the TNT Mill and the regular removal of dust from the Mill kept the incidence of such poisonings down to acceptable levels.

But Lord Chetwynd was also concerned for the welfare of his workers – providing good food and rest facilities – and also he saw the value of sport and entertainment – including a ladies football team and a ladies tug-of-war team. A newspaper report at the end of the war described:

‘…sumptuously fitted baths, canteens, change rooms and outdoor recreations. It was provided with a band which played dance music at meal time; a swimming pool nearby for the men and spacious sports grounds at Chilwell, Long Eaton and Beeston.’ (Mansfield Reporter – 27 December 1918)

By early 1918, there had been seventeen explosions at the factory, ten in the Press houses and five in the Experimental House but none had resulted in serious injuries or fatalities. The remaining two had occurred in the Melt House, both resulting in the loss of life – one man on 24 July 1916 and two men on 5 October 1917.

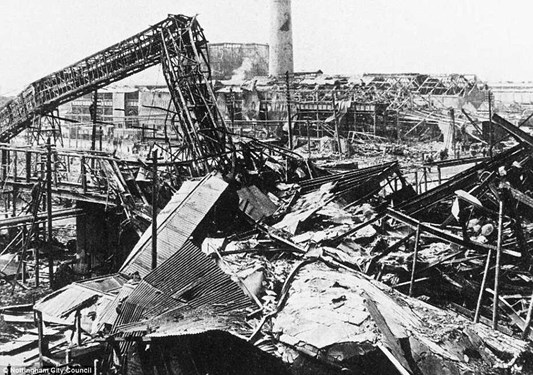

Monday 1 July 1918 was a hot day……at 7.12pm there were a series of almighty blasts in which the Mixing House, Mixing House Extension, TNT Mill and TNT Stores were completely destroyed. The explosion was heard many miles away and the shock waves shattered not only glass in the Factory but also in houses and buildings up to three miles distant from the blast.

Above : The Vanesta factory, Silvertwon, East London after the 19 January 1917 explosion © IWM Q 15364

Above: The damage caused by the explosion on 1 July 1918 IWM

Eye witness accounts from survivors told a grim tale:

‘…..there were bodies everywhere, black with burns, some dying, lots dead’.

‘…Men, women and young people burnt, practically all their clothing burnt, torn and dishevelled, their faces black and charred, some bleeding with limbs torn off, eyes and hair literally gone…’.

‘…the streets were full of carts taking the bodies away’

There was no panic within the workforce as the able-bodied shepherded the injured out of the factory and away from the danger of any further explosions. Local people rushed to the scene to assist and within two to three hours, all of the injured had been removed from the site of the explosions. Lord Chetwynd arrived at 10pm – he had been suffering from influenza - and his first enquiry was for the wounded.

A total of 134 were killed, with 246 injured. Many of the dead were taken to Attenborough Church where they were laid out, many unrecognisable.

Work continued through the night with the result that when the day shift returned at 6am on the next morning, some work resumed in the Shell Stores and the Melt House, but only ‘limited production’ was achieved as most of the time was spent clearing up the damage and getting everything ready for a general resumption of work the following day. Amazingly, on the day after the explosion, only 14 failed to turn up for their shift.

Expressions of sympathy were received from all quarters, including Winston Churchill who had succeeded Lloyd George as Minister of War:

‘…the decision to which you have all come to carry on without a break is worthy of the sprit which animates our soldiers in the field. I trust the injured are receiving every care’.

And from the King:

‘….It is with feelings of admiration that His Majesty has heard of the gallantry displayed on all sides and of the prompt resumption of work this morning’.

Within two days of the explosion, shellfilling continued at Chilwell whilst restoration work continued alongside production work. Meantime, the first funerals of those killed were carried out – although in many cases, it was impossible to identify the bodies. The first 34 bodies were buried in one of three mass graves at Attenborough Church on 4 July 1918 with further burials in the coming days.

Above: St Marys, Attenborough

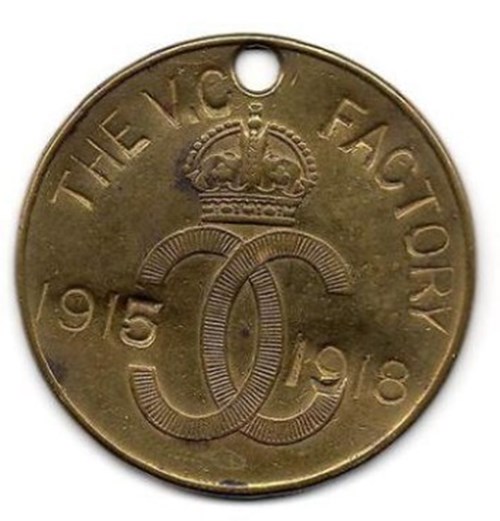

On 9 July 1918, the Times newspaper reported on a speech made by Mr F G Kellaway, MP in a piece entitled ‘VC for a Factory’. Kellaway had concluded his remarks with:

‘…The French, who have a very sound instinct in matters of this kind, gave the highest military distinction in their power to the citadel of Verdun, when it defeated the great German advance of 1917. I wonder why we should not emulate that example and give the Victoria Cross to this brave factory’.

….and thus, Chilwell, the VC Factory was born. In addition, the Works Manager, Arthur Bristowe, was presented with the Edward Medal (the industry equivalent of the George Cross) for his heroism, and seventeen of the factory’s workers – eleven men and six women – received the Order of the British Empire for acts of bravery in the New Year Honours in 1919.

A memorial cross was erected on the site of the mass graves.

Above: The original cross

A more permanent memorial was later erected although it was in located on an Army base.

Above: The permanent memorial

The cause of the explosion was the subject of an Enquiry later in July 1918. Lord Chetwynd believed that sabotage was the cause and even named those he suspected as ‘disaffected workers’ but other potential causes were also mooted - to this day, it is not possible to be certain as to the cause. The report was never published.

The identity disc worn by workers bore the title ‘the VC Factory’

Above: The disc worn by workers at the factory

Article contributed by Jill Stewart, Honorary Secretary, The Western Front Association

Further reading and links

The Chilwell Story by Captain M J Haslam, RAOC - 1982

Historic England

IWM Collections