Death on the shoreline: The foundering of HMHS Rohilla off Whitby : 30 October 1914

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Death on the shoreline: The foundering of HMHS Rohilla off Whitby : 30 October 1914

For the vast majority of members of the British public, the outbreak of the First World War was not something that meant much in the early weeks, Other than crowds of men responding to Kitchener’s call for volunteers, the war was probably something that was only read about in the newspapers. It was obviously different in France and Belgium where much of the population of these countries had firsthand experience of what the war meant.

The lack of ‘first hand’ experience of the war came to a halt for one small east coast town on 30 October 1914 with a maritime disaster literally a stone’s throw from the shoreline.

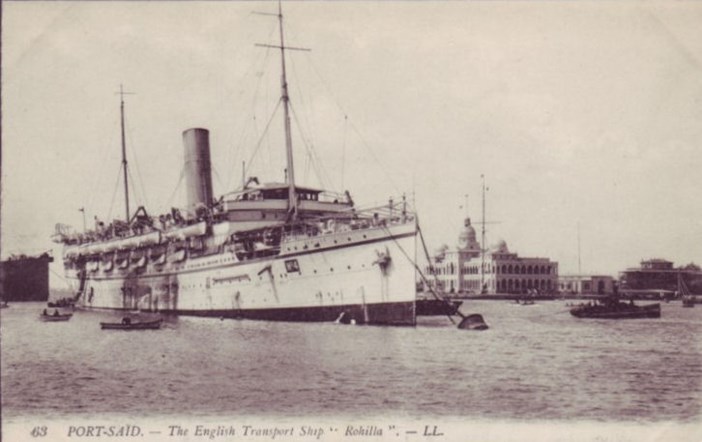

On the outbreak of the war the British Government set in motion plans to convert vessels into hospital ships. One of these was the transport of the British India Steam Navigation Company ‘Rohilla’.

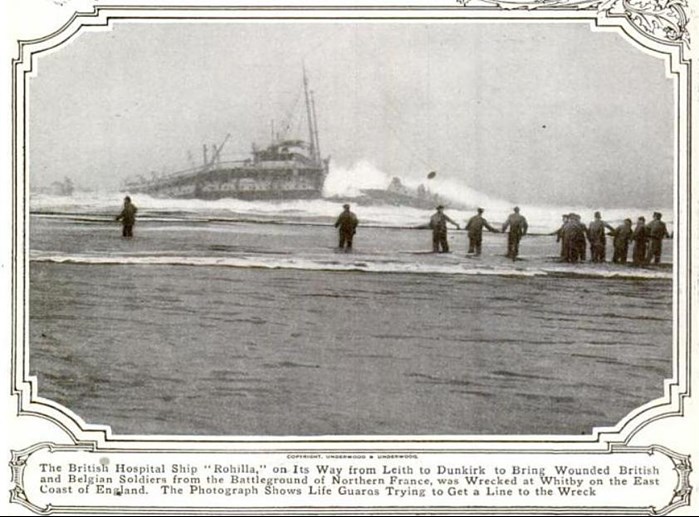

On 30 October 1914, sailing from South Queensferry, Firth of Forth for Dunkirk to return wounded soldiers to the UK, the ship ran into a ferocious storm off the east coast of Yorkshire. There followed a chain of events that were directly attributable to the wartime regulations.

The Rohilla’s captain (Captain Neilson) had not navigated the North Sea coast before (he had plenty of experience sailing the ship on its usual pre-war route to India) and had to contend with the threat of German submarines and mines. Coastal navigations lights were extinguished and navigation was by dead-reckoning. Taking a fix off the Farne Islands, (off Northumberland) the ship travelled down the coast, but the storm and lack of navigational aids meant that the ship was perilously close to the coast.

Off Whitby, the coast guard on shore spotted the Rohilla and realized she was in danger of hitting a reef which – had the bouy not been removed due to the war – would have been well lit to warn off shipping.

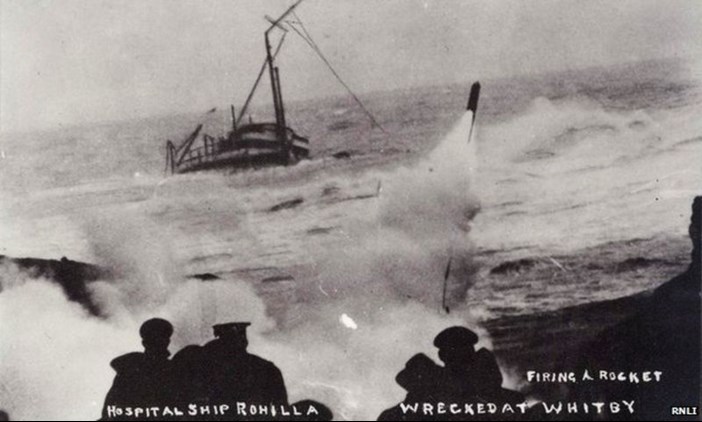

Despite attempting to signal the ship to veer away from the treacherous rocks, contact from the shore proved impossible and at 4.10am on 30 October the vessel grounded with a mighty judder on the reef only 600 yards from the shore.

Lifeboats from the town and from up and down the coast were eventually launched but the conditions were appalling. The conditions meant the Rohilla’s own boats could not be safely loaded and launched and the ship started to break apart and sink. The ship broke in three sections: first the stern sank, killing most of the people on board that section of the ship. Those left on the rest of the wreck were stranded as it broke up over the course of three days.

The sinking was a long process and must have been terrifying for the 229 on board. The townsfolk could do nothing to assist as the drama unfolded over the coming days. Over the course of the next three days, some of those on board who attempted to swim to safety in the foaming seas were rescued, though many were tragically lost. Thankfully lifeboats were able to rescue some of those on board.

In all, 146 of the 229 on board, including Captain Neilson and all the nurses were saved, including Titanic survivor Mary Kezia Roberts.

Bodies began to wash ashore and were collected by the townsfolk of Whitby, and some were never found.

Some of the lifeboat crew were awarded medals for their bravery. Many of the crewmen from the Rohilla were buried in Whitby where the owners of the Rohilla erected a monument to the ship's loss.

It was clear from advances in shipbuilding and vessels of that era that a new breed of Lifeboat was needed and shortly after the loss of the Rohilla, Whitby's outdated rowing boat was replaced with a motor lifeboat.

The Royal National Lifeboat Institution lists this event as one of the worst services in its history. Numerous medals were awarded.

The wreck of the Rohilla, or what is left of it can still be seen to this day when the tide is out down at Saltwick Bay.

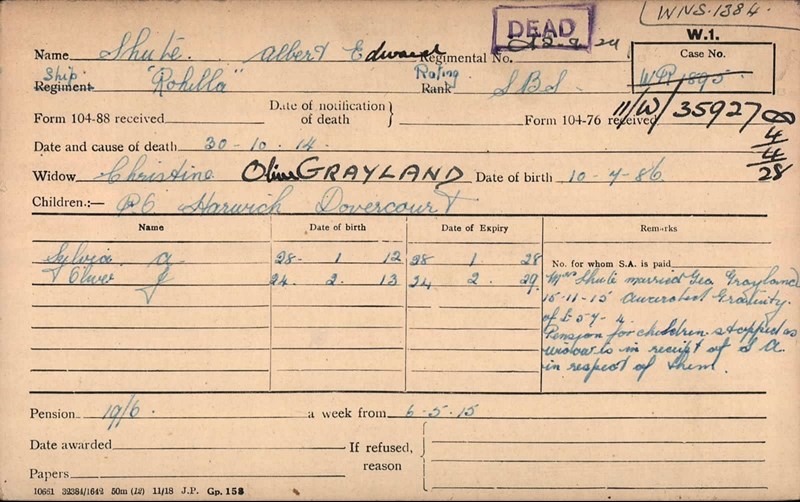

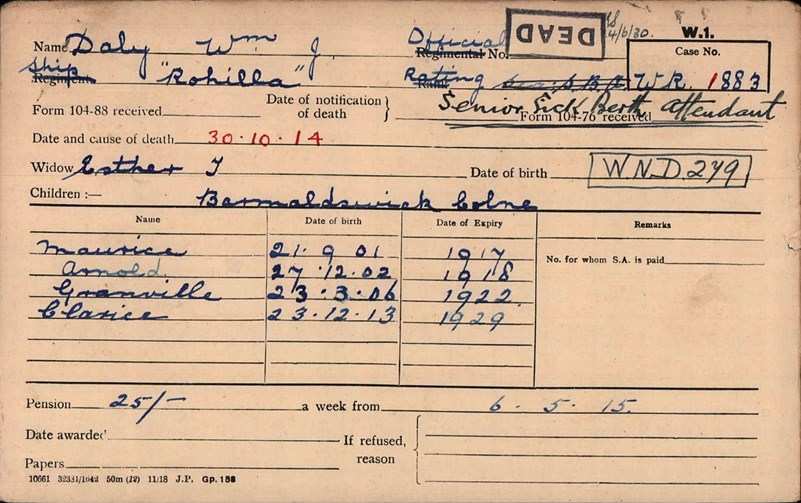

Using the WFA’s Pension Records we can see details of quite a number of cards (well over 80 in total) of those who were lost in this home-front tragedy.

Moving video footage from the British Pathé is available to watch via this link HMHS Rohilla footage

Article by David Tattersfield, Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association