Finding Captain Brooke: The oldest Regimental Medical Officer to be killed in the war

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Finding Captain Brooke: The oldest Regimental Medical Officer to be killed in the war

On 27 May 1918 the Headquarters of the 1st Battalion Wiltshire Regiment was surrounded during a desperate rearguard action at the village of Bouffignereux on the Aisne. Numerous officers and men were killed, with others being wounded and taken prisoner, including the battalion's commanding officer. The unit’s war diary – perhaps inevitably – does not provide numbers of casualties, but it would seem that more than 40 officers and men were killed, with hundreds of others wounded or missing. Virtually all of the fatalities have no known graves.

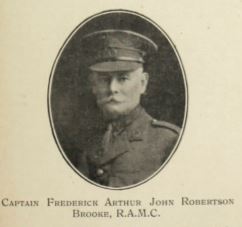

One hundred years later, one of the graves of a missing officer has been located. Captain Frederick Brooke was the battalion’s Medical Officer. Research suggests that, at the age of 55, he may have been the oldest Regimental Medical Officer attached to an active service battalion to be killed on the western front. This is his story.

Above: Frederick Brooke RAMC

The German Spring Offensives of 1918 were – as is well known – the final ‘throw of the dice’ for the Germans. Had any of these massive assaults succeeded, it may have been possible for the Kaiser to bring about if not victory, at least a negotiated peace on terms far more favourable than those agreed on 11 November. Although the men on the ground could not see into the future, the importance for the allies in stopping these German attacks cannot be under-stated.

After the failed attacks in March and April (known as ‘Michael’ and ‘Georgette’), the third of the German ‘all out’ attacks commenced on 27 May on the blood-soaked front of the Chemin des Dames ridge.[1] This attack, known to the Germans as ‘Blücher-Yorck’ but to the allies as the Third Battle of the Aisne was aimed at the French-held positions north-east of Paris adjacent to the infamous Chemin des Dames ridge. The German thinking was that in order to avoid losing Paris, the British would send reinforcements to the sector making a renewed attack in Flanders more likely to succeed.

Unfortunately for those concerned, some British Divisions had already been sent to the sector in order to recover from the earlier German offensives. The sector was quiet and, it was thought, a good place to rest and absorb new drafts. Thus it was that the 25th Division, which had suffered a significant number of casualties during the ‘Georgette’ offensive, was sent south to recuperate.

Among the battalions in this division was the (theoretically) ‘regular’ 1/Wiltshires. In command of the battalion was Lt Colonel Edward Keith Byrne Furze, DSO, MC. He had been appointed CO on 4 May when the unit was still in the Ypres sector. Within five days, the battalion was entrained for the Aisne.

The Third Battle of the Aisne

Due to the French sector commander, General Duchene, not conforming to the new method of elastic defence, the Chemin des Dames sector was heavily manned in the front line and instructions had been issued to give no ground in the event of an attack. These obsolete tactics were to be a disaster for the French and British. When the German surprise attack was launched on 27 May, positions were over-run and many of the defending troops were trapped on the ‘wrong’ side of the River Aisne.

In desperation, the British Corps commander, Lt-Gen Hamilton-Gordon requested to be allowed to send forward a brigade of his reserve formation (the 25th Division) to assist the units in the front line. Grudgingly, it would seem, and far too late to be effective General Duchene agreed to this at 7.30am, and Hamilton-Gordon was given the 25th Division to be used as he saw fit. However, by mid-morning the forward zone had crumpled in the face of the German onslaught and the Battle zone had in many parts also fallen.

The line here turned at right-angles and the German attack was from two directions, southerly across the River Aisne towards Gernicourt and westerly towards the line held by units of the 21st Division. The sector between Cormicy and Bouffignereux faced east and it was here units of the 21st Division held the line and to where the three battalions of 25th Division’s 7 Brigade were sent. One of the battalions of the brigade was the 1/Wiltshire led by Lt Col Keith Furze.

Above: Bouffignereux village (author)

A detailed account of the day’s events has been left by a German officer (Leutnant Otto Lais) who took part in the operation in this sector. The following is extracted from Imperial Germany's Iron Regiment of the First World War, History of Infantry Regiment 169. The author is grateful to John Rieth for his permission to use the following passages.[2]

Squad-by-squad, enough Germans made it across the river and canal so that they could manoeuvre against the French troops immediately before them. One of the German leaders was the red-haired Leutnant Ries, described by Lais as being completely unflappable. Filthy dirty, and with a long stubble of a red beard, he attacked with great fury. Nearing the French position, he yelled with his rich tenor voice ‘a’ bas les armes! (Down with your weapons!).

Directly ahead was the ominously silent Gernicourt Woods. Due to the large concentration of the special ‘yellow cross’ gas targeted there, most German units bypassed the woods to open fields on either end.

Above: Gernicourt Woods. As the Germans headed south of the village of Gernicourt they were faced with this woodland. Bouffignereux is just two miles beyond the wood. (Google Street View)

A small storm troop group, wearing well-inspected gas masks, was ordered to scout the centre of the woods. There they found that the yellow cross gas indeed functioned as billed. The crews of an entire British artillery battery lay dead. Elsewhere, others were found dying or suffering in horrible agony.

German small units breached the Aisne in greater numbers, forcing the British to abandon their defence of the southern end of the Pontavert Bridge. German pioneers quickly set up more substantial bridges across the river and canal that could support wagons and vehicles. The Aisne River was now fully under German control.

The next line of British resistance stood at the small village of Bouffignereux, one mile further south of Gernicourt Woods. The ground between Bouffignereux and the Gernicourt Woods were open fields.

To the east was a forest where a mounted British artillery battery paused along a path in the midst of a copse of alder bushes. In addition to the battery, the confused British retreat left a collection of supply, medical and munitions wagons becoming tangled in the small forested pathways.

At 10:30am, the 1/Wiltshire Regiment, came up from reserve positions in an attempt to slow the German advance.

The main assault on Bouffignereux took place at 5:30pm.

Lais arrived in Bouffignereux just after the village was stormed. The intensity of the fighting was evidenced by the many dead British soldiers lying throughout the village streets. Still-warm corpses were dragged to the sides of houses so wagons would have free passage. At dusk, a large group of prisoners, described by Lais as having a more polite demeanour than those taken in the forest, gathered unguarded in the village centre, waiting for evacuation to the rear. Artillery units entered the village with a heavy battery taking position in the church courtyard.

That evening, the Germans in Bouffignereux feasted on British rations. They had not had the opportunity to sample British food since taking prisoners in the 1916 Somme Campaign. With great delight, Lais’ orderly, filled any extra space in the wagon limbers with such delicacies as white bread, butter, peach jam and corned beef.

It is likely that a number of British units stood in the way of the German advance described above. From examining the war diary of the 22th Durham Light Infantry (the pioneer battalion to 8th Division) we learn that this unit was tasked with defending the canal bank just north of Gernicourt. Overwhelmed, the companies of the 22/DLI fell back, one to the Bois de Poupeaux (south of Gernicourt) and ‘at about mid-day got in touch with the 1/Wiltshires in Bois Grand Bellay’ (this is just north west of Bouffignereux). The 22/DLI war diary goes on to describe how men from the battalion ‘held out until they found the enemy coming up in the rear’ and so made their way along a trench and took up a position south of Bouffignereux. The 22/DLI diary goes on to say how the enemy was held in front of Bouffignereux, but when one of the (British) flanks had given way, a retirement was ordered to the high ground above Guyencourt.

The 1st Wiltshire – summary and interpretation

As mentioned above, the 1/Wiltshires were thrown into action during the morning of 27 May. By then it was far too late as the Germans had advanced across the River Aisne. The battalion was ordered forward at 7.30am to cover the retirement. The battalion’s war diary records ‘Captain Priestley with three companies takes up position further forward’.

Nearly three hours later, at 10.15am, a further note in the war diary records ‘Battalion again moved forward and holds line in front of Bouffignereux’. This suggests two distinct movements with the line ‘in front of Bouffignereux’ being held until late afternoon. There is no evidence of any attacks being made on the battalion during this period.

But whilst no frontal assault was made, the war diary records ‘Enemy shelling constantly [on] Battalion HQ, machine gun fire continually sweeping roads and tracks to HQ and front line. Supplies of SAA (Small Arms Ammunition) etc were [unreadable, but possibly ‘however’] maintained.

At 4.15 Captains Priestley and Arnott report situation to CO (ie Lt Col Furze) at Battalion HQ. Capt Priestley wounded still remains at duty.

The 1/Wiltshire’s war diary states:

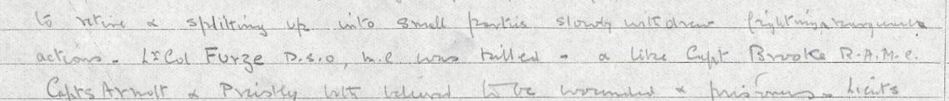

“5.30pm: Enemy attacked [with] greatly superior forces [and] the battalion was compelled to retire and splitting up into small parties slowly withdrew fighting rear-guard actions. Lt Colonel Furze DSO MC was killed and like Capt Brooke RAMC, Captains Arnott and Priestley both believed to be wounded and prisoners. Lieuts Sands, H Reid and Duley were wounded & evacuated. Also 2/Lt H Anderson and 2/Lt AM Reid.”

This passage from the war diary is very important to the story and will be examined in further detail below.

Fortunately we have a number of accounts of what happened. L/Cpl Talbot Mohan who was with the 1/Wilts left a personal diary which tells of the events early that day:

‘We were entirely caught by surprise this time, and before anyone realised what was happening the Germans were back as far as our artillery. The gunners had no time to destroy their guns and as far as our division was concerned, they lost them all. We therefore had not a gun behind us – nothing to cover our retreat but machine guns. I never even saw one aeroplane of ours, though the air was alive with enemy planes.

‘It can be easily seen that under these conditions all we could do was to retire, doing as much as possible of a rearguard action against such heavy odds… The lads were soon in the thick of it and suffered heavily. The Germans came over in massed formation and although our fellows put up a splendid fight it was impossible to hold them. Nearly the whole of B Company were either killed or taken prisoner.’

Diary of Corporal Talbot Mohan, 1st Battalion The Wiltshire Regiment, 11 April to 23 September 1918 (Courtesy of the National Army Museum)

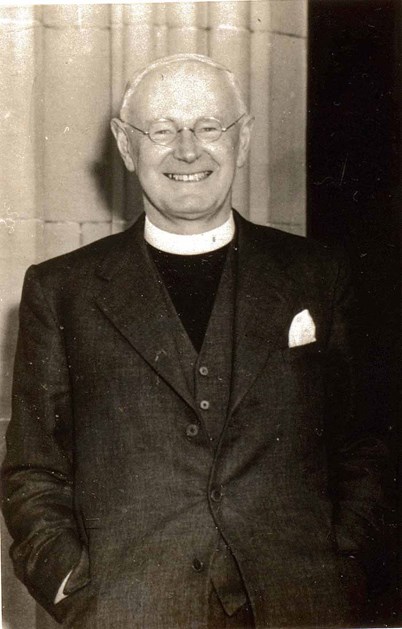

Above: Canon Talbot Mahon in later life (NAM)

During the course of the day, 38 ‘other ranks’ were killed. Only two of these have known graves, with these ‘missing’ men being named on the Soissons Memorial.

In attempting to understand what happened to the battalion on this day, we find that the war diary was somewhat inaccurate in terms of the officers it names. We are helped by the statement given after the war by Lt Reid who (as all officers were obliged to do) explained the circumstances of his capture. Reid reported

“As Lewis Gun officer I was attached to Battalion HQ and about 3pm two of our companies were driven back on to us and very shortly after the Germans were firing at us from three sides. Orders were given to fall back into a wood about 200 yards behind us.

“While on my way I saw Capt Arnott of the same battalion supporting the Commanding Officer, Lt Col Furze, DSO who was lying on the ground badly wounded. I went to assist him and by the time we had bandaged him (the CO) up we were the only un-wounded men left on the scene and the Germans were surrounding us and barely 75 yards away. Not seeing any chance of escape we were forced to surrender.”

Captain Arnott’s capture statement is remarkably similar

“At 3pm my company was driven back and I formed up again round Battalion HQ in conjunction with ‘A’ Company. Shortly afterwards as casualties were heavy owing to our being practically surrounded we were order to withdraw and hold a wood about 300 yards in rear. On withdrawal I saw the Commanding Officer fall wounded and stopped to give him first aid. Lt Reid the battalion LGO came over to help me. By the time we had finished we were cut off by the Germans and were forced to surrender.”

In his file at The National Archives, there is a clue that this did not satisfy the post war enquiry team, as Arnott was asked ‘whether there were no stretcher bearers or other ranks at hand, as your place was with your men’.

Arnott replied a few days later “…there were no stretcher bearers at hand and only casualties amongst the other ranks who were subsequently captured. I had one surviving officer with the remains of the company and he had orders from me to carry on whilst I was receiving orders from the Battalion HQ. It was there that the enemy made the rush and Battalion HQ was cut off. I could not get back to my men as we were surrounded.”

Within the officer’s file of Captain Priestley, we have a letter from Private Harry Woodley (number 27616, of ‘D’ company) who reported the circumstances around Priestley’s death.[3]

“I was with this Officer on the day he was reported missing from, viz 27 May 1918, and it was late in the afternoon of that day when we were retiring that Captain Priestley was hit in the throat by my side, and I am sure it was fatal. It was only moments after this that I was taken prisoner. Captain Priestley had been slightly wounded earlier in the day in the hand.”

This statement nicely corroborates the reference in the war diary to Priestley being wounded, but remaining on duty.

A report in the file of 2/Lt Turnbull quotes a statement made by Captain Arnott that ‘While being marched off as a prisoner I saw the body of an officer lying close by. I went over and recognized 2/Lt Turnbull who was dead and must have died instantly as he was shot through the heart. (Turnbull was a member of the DLI, but attached to the 1/Wiltshires.)

Again, a report by Captain Arnott is detailed in a post-war letter to the relatives of Lt OL Desages. Arnott is quoted as saying He [Desages] was severely wounded in the abdomen and the doctor gave no hope of his recovery”. Desages, as with all but two of the officers and men killed this day is commemorated on the Soissons Memorial to the missing.

The reference to ‘the Doctor’ strongly suggests this is Captain Frederick Brooke, the attached RAMC Medical Officer who is mentioned alongside Furze in the war diary. The implication from the war diary (confused by a lack of punctuation) suggest Brooke was believed to be wounded and a prisoner. The war diary – shown below – is not totally clear at this point on the fate of Brooke, although it clearly states that Furze was killed. As will be seen later, this is inaccurate in terms of the fate of both these officers.

Above: War Diary, 1/Wilts (TNA)

Frederick Brooke

Frederick was born on 31 March 1863 in Caxton, Cambridgeshire, the son of Thomas Brooke (a surgeon), and his wife Annie.

Frederick’s father registered him to start at Epsom College in September 1876. By that time the family was living at Langport in Somerset. He was joined at Epsom by his brother Tom in 1877. (Besides Frederick and Thomas, there were three daughters living at home Evelyn aged 20, Dora, 13 and Florence, 10.)

Frederick left Epsom College in April 1881 and studied medicine at the London Hospital. He interrupted studies for some reason between November 1885 until June 1891. In the 1891 census (taken on 5 April) the 28 year old Frederick was working as a medical assistant in Derbyshire and boarding at Milford Road, Duffield, in Derbyshire. He took the MRCS and LRCP diplomas successfully in 1894.

Frederick married Constance Blanche Moore in 1895 and fathered 7 children: including Cecil Rupert who was born in1896,

At the time of the 1911 census Frederick was working as a locum at Charnwood, Buckhurst Hill, Essex. For a few years he was in practice at West Bridgeford, Nottinghamshire and prior to joining up, he was in practice at Charlbury, Oxfordshire.

He took a temporary commission as a Lieutenant in the Royal Army Medical Corps on 10 July 1915 and was promoted to Captain the following year.

Remarkably, a diary has survived detailing Frederick’s activities during 1917, which has helped immeasurably to build up a picture of his activities the year before he was killed.

We know Captain Frederick Brooke reported for duty on 7 September 1916 to the Number 5 Convalescent Depot at Cayeux (about 30 miles south of Etaples on the coast) and adjacent to Saint-Valery-sur-Somme.

His diary makes reference to his friend Captain Hutcheson, and amusingly references a Cricket match when Frederick’s team were bowled out for just seven runs, in reply to the other team’s score of 54. Neither Frederick or ‘Hutch’ made a single run. His diary also poignantly records letters sent to and received from his son Cecil who was serving with the 8th/10th Gordon Highlanders part of 15th (Scottish) Division. He managed to visit Cecil at Arras on 20 March, just a few weeks before the offensive at Arras. This was the last time he was to see his son, as Cecil was killed in action on 24 April.

Frederick was taken ill soon after his visit to Cecil, being admitted to hospital at Abbeville suffering from ‘boils’.

On 31 March he was able to dress for the first time since being admitted to hospital. He noted it was his birthday, and received a letter from his wife, Connie which must have cheered him up. ‘Hutch’ also visited him. He was able to go home on sick leave for three weeks from 6 April.

There are numerous references in his diary, written months later, to his deceased son, Cecil.

Returning to France on 26 April, he rejoined the No 5 Convalescent Depot, but on 30 April he recorded in his diary: Today about 8.45am I heard that my dear boy Cecil had been killed in action at Arras on Apr 24. He was killed between 5-6pm having been, so the NCO writes me, ‘struck on the left temple by shell and dying a few minutes afterwards’.

Early May saw a move from the convalescent depot to a Casualty Clearing Station named ‘Lucknow’. Later in May he went up to Arras to try to find Cecil’s grave, but returned without finding it. Later still in May he was went to 136 Field Ambulance, (part of 40th Division) based at Fins. Another move in June was to 24 Field Ambulance (8th Division) near Merris.

Above: Officers and men of a Field Ambulance somewhere in France (National Library of Scotland)

Carrying on his somewhat peripatetic existence, in June he was temporarily attached to XIV Corps to help with the vaccination of German prisoners.

In late June he was sent to ‘B Siege Park’ as Medical Officer but this was a short appointment as he then moved again to 136 Field Ambulance.

He took up various appointments in the UK between July and December, but on 23 December he notes he was flown to France in an RE8 but returned to the UK within a few days.

The diary ends on New Year’s Eve 1917, so his precise movements in 1918 are not known. However, it is believed he was working as a physician to the Tidworth Military Hospital before becoming Medical Officer for 1st battalion Wiltshire Regiment. This appointment to the 1/Wiltshires would have been some time after 12 April 1918 when the battalion’s Medical Officer at the time, Lt RM Evens, was reported as ‘missing’. (It seems that Evens was one of the medical officers supplied by the USA to many units) .

It is perhaps an indication of the desperate shortage of Medical Officers that Frederick – aged 55 was assigned to a front line infantry battalion. It must be assumed that he volunteered for this role, as his age would surely otherwise have ruled him out.

We don’t know exactly what happened to Frederick on 27 May 1918. As the Medical Officer to 1/Wiltshires he would almost certainly have been with the battalion Headquarters and his movements would possibly have been similar to those of Lt Col Furze.

There exists a letter from Captain Guy Pullan, to the mother of Lt Col Furze in which he talks in some detail about the death of Lt Col Furze. As will be revealed, this is however fundamentally flawed, in that Furze was not killed !

01.06.1918 Letter from ‘Guy Pullan’ – 7th Inf Bgde HQ BEF

My Dear Mrs Furze,

I am hoping someone at Division has already written to you and told you the terribly sad news about Keith. I have tried to find time but we are only just out of the line after all this fighting and withdrawing. I will give you the details I can now but I will let you know everything when I can get leave.

The Bgde was in reserve at the commencement of the battle but at 0800 on Monday 27th we took up a position where we hoped to hold the Bosche. I walked most of the way up with Furzzy and he was in great spirits and quite happy. His Battalion had not been in their positions more than 2 hours when the Bosche attacked them. He was driven off repeatedly but eventually worked round the flanks and completely surrounded the position.

It was while your son was organising a counter attack that the Bosche rushed from all sides the position the 1st Wiltshires held and it was a case of rapid withdrawal or complete surrender. Keith waited until all his Headquarters personnel had withdrawn under very heavy machine gun fire and then went himself with a Private.

They hadn’t gone 50 yards when poor Keith was hit by a machine gun bullet in the groin and died practically instantly – but loudly telling his orderly to get away first. The man however waited until your son was dead and then managed to get away. I have had this account corroborated by 3 or 4 men.

I didn’t hear of it until later in the day when that part of the country was in enemy hands or I would have tried to get his body away. I am absolutely heartbroken about it and have lost my best friend in the world.

[The letter continues with a great deal of further detail, but ends…]

I shall be only so glad to do anything I personally can for you. I trust you will bear up as well as possible and please accept all my sympathy.

Yours very sincerely,

Guy Pullan

Above: Colonel Keith Furze, Military Knight of Windsor, 1955-1971 (https://www.stgeorges-windsor.org/image_of_the_month/a-first-world-war-hero/)

Despite the very detailed and apparently corroborated account, Lt Col Furze survived the war. Clearly the war diary’s statement was incorrect and the ‘fact’ of his death was compounded by Pullan’s letter.

Almost certainly accompanying Furze at the Headquarters was the battalion’s medical officer, Frederick Brooke.

As detailed above, the war diary implies that Brooke, along with Captains Arnott and Priestley was ‘wounded and prisoner’.

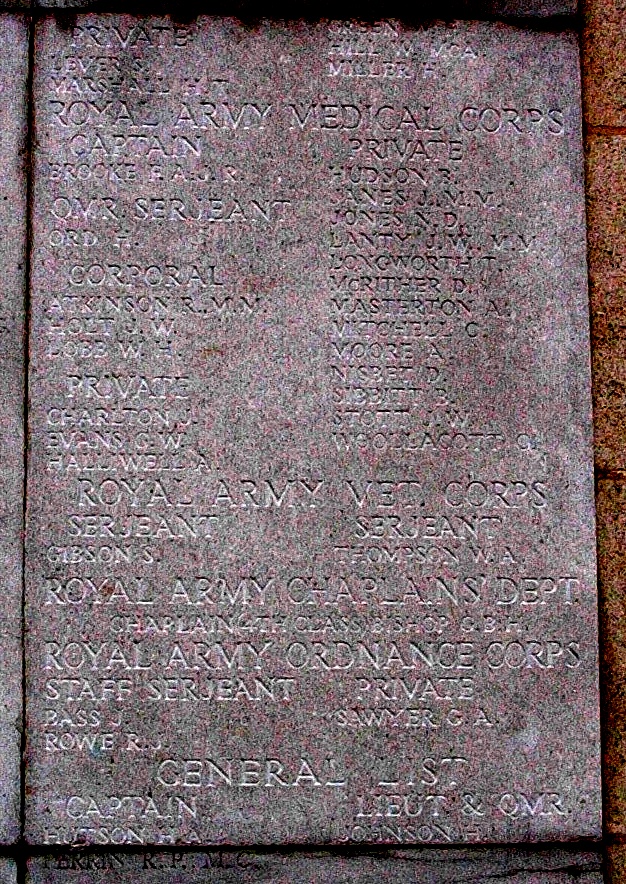

Regrettably, Brooke (unlike Arnott) was not to survive. There are no surviving accounts detailing Frederick’s last moments and his name was added to the Soissons Memorial to the missing. The memorial lists 21 from the RAMC who fell in action in this area and have no known grave. Significantly, for what was to occur, Frederick is the only officer from the RAMC named on this memorial. For over 100 years Frederick Brooke has been named as one of the ‘missing’ on the magnificent Soissons Memorial.

Above: The panel on the Soissons Memorial showing the RAMC 'missing'. Captain Brooke is the only officer named.

Above: Soissons Memorial (CWGC)

Discovery of grave - 2018

In May 2018 I attended a ceremony at the La Ville-aux-Bois British Cemetery for the re-dedication of a headstone for Major Octavius Darby-Griffith.

After the service I walked up and down the rows of headstones in this cemetery that I knew rather well. Near the back of the cemetery my eye fell on a headstone in Row J of Plot 2. This detailed ‘an unknown Officer of the Great War, of the Royal Army Medical Corps.’

Above: The headstone of the 'unknown officer, RAMC' at La Ville-aux-Bois British Cemetery (author)

Of course, at the time I was in ignorance of the story of the 1/Wiltshires, and equally did not know that there was only one RAMC officer listed on the Soissons Memorial. However, it occurred to me that the number of RAMC officers who fell in this sector in May 1918 would not be large.

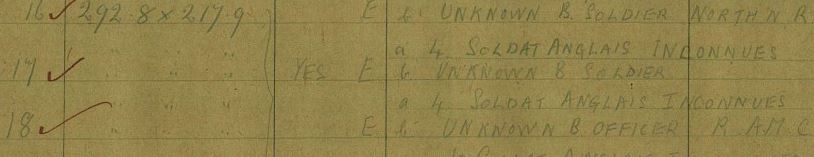

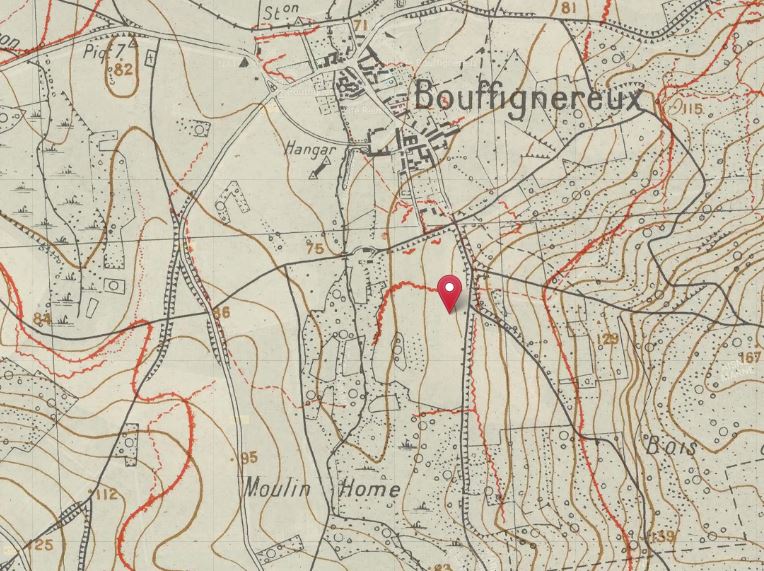

Returning home, I set about researching the RAMC officers who fell on or near the Chemin des Dames in 1918. It was indeed a small number: Frederick Brooke was the only candidate. But of course, the BEF had been in the sector in 1914. I needed to be sure this was Frederick’s grave. This was straightforward to confirm, as the graves registration unit when exhuming the body of the ‘unknown RAMC officer’ kept a log of the locations where the original burials were made. This was noted as from (map reference) 292.8 x 217.9.

Looking at contemporary French 'trench' map (this can be found on the WFA’s new ‘TrenchMapper’ portal) '292.8 x 217.9' is just a few yards to the south of the village of Bouffignereux.

Above: a portion of the CWGC’s exhumation report showing an unknown officer, RAMC being located at 292.8 x 217.9. It is notable that there are a number of other 'unidentified' men who were exhumed from exactly the same map reference as the 'Unknown officer RAMC'. They are buried in adjoining graves.

The exact map reference is marked on the map below. (via the WFA's 'TrenchMapper)

Above: The same spot marked on ‘modern map’ (via the WFA’s TrenchMapper)

Above: The track running south of the village of Bouffignereux, view looking north. The exhumation would have been from the field to the left (author)

All of this was submitted to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission in 2018, and subsequently passed to the Joint Casualty and Compassionate Centre (JCCC - part of the Ministry of Defence).

Having agreed with the submission, the JCCC tracked down Frederick’s living relatives, including his granddaughter and great granddaughter. As a result there will be a ceremony to dedicate the new headstone at La Ville-aux-Bois British Cemetery on 6 September 2023.

Other men from the battalion: burials in the same cemetery?

Although just two of the 1/Wiltshire’s fatalities who fell in the attack at Bouffignereux have known graves, neither are buried at La Ville-aux-Bois British Cemetery.[4]

The Germans, in attempting to force the attack forward, would have had little time to identify and record the names of the British soldiers who had been killed around Bouffignereux. But within La Ville-aux-Bois British Cemetery are scattered a number of headstones to Wiltshire Regiment soldiers, including a row of seven.

Above and below: Seven Wiltshire headstones. These are without doubt the men who Frederick served with and would have known during his short stint as the battalion’s Medical Officer (author)

Further research into these seven ‘Unknown Wiltshire’ headstones is quite revealing

Using the map references for the original burials, we can see that the men were buried in ones and twos south of Bouffignereux. The map below pin-points these seven burials. Three men were buried at two spots just north of Guyencourt. Another two were buried together just south of Guyencourt. Two other single graves were located about a mile south west of Guyencourt on the road to Ventelay.

Above: The marks show the original burial positions of Frederick Brooke (at the top) and others from the 1/Wilts (via the WFA's TrenchMapper)

It would seem that the remnants of the battalion, after suffering heavy casualties at Bouffignereux retired via Guyencourt towards Ventelay, possibly losing men in skirmishes en-route.

Post war commemoration

Epsom College commemorated its ‘old boys’ with a brass plaque after the war. For some reason – lost in the mists of time – Frederick was initially omitted, and subsequently added albeit out of order and with his initial ‘F’ incorrectly detailed as ‘S’.

Above: The Epsom War Memorial. Brooke is out of order at the bottom of the centre 'panel' of names: this suggests he was originally omitted from the memorial when it was created after the war. (Epsom College)

Despite his age and having lost his son at the Battle of Arras, Frederick Brooke committed himself to serving in a front line infantry battalion and was killed whilst his unit was under a heavy attack. That his body was ‘lost’ would have been yet another blow to his grieving family. It is pleasing that – despite the passage of time – the last resting place of Frederick Brooke has been identified and now can be visited by his relatives.

David Tattersfield

Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful to the following for their kind assistance in making this article possible:

Howard Anderson and Bill Frost (WFA TrenchMapper gurus)

Elizabeth Manterfield for details of Frederick's back-story via the RAMC archives.

John Rieth

Jill Stewart

Ben Wilberforce-Ritchie (for providing the letter that Guy Pullan sent to Mary Furze, Keith Furze’s mother)

Rebecca Worthy (Epsom College archivist).

Also my gratitude to two of Frederick's relatives:

Diana Brooke (granddaughter of Frederick Brooke)

Ana Retallack (great granddaughter of Frederick Brooke)

who between them deciphered Frederick's surviving 1917 diary

Further Reading

Aisne 1918: The phantom Sector by David Blanchard

The Aisne Again: The Essence of the Blitzkrieg (video on the WFA's YouTube Channel)

Footnotes:

[1] This ignores the one-day attack codenamed MARS aimed at Arras.

[2] The account details the actions of IR 169 as it assaulted over 8th Division lines, participated in the attack at the Bois de Buttes, and attacked over the Aisne between the Pecherie and Pontavert. The primary German source comes from the memoirs of Leutnant Otto Lais, who served as the Executive Officer for IR 169's 2nd Machine Gun Company during this battle.

[3] Priestley was originally commemorated on the Vis-en-Artois memorial to the missing but his name is now (correctly) listed on the Soissons Memorial to the missing addenda panel.

[4] Private Arthur Andrews is buried at Hermonville Military Cemetery Private Charles Fowle is buried at Chambrecy British Cemetery).