From ceremonial duties to First Ypres and beyond: The 1st Life Guards and their single worst day of the war

- Home

- World War I Articles

- From ceremonial duties to First Ypres and beyond: The 1st Life Guards and their single worst day of the war

This is a brief account of one cavalry regiment's war which reached its nadir in unlikely circumstances whilst they were in a supposedly safe location on the French coast re-training for a new role. The story starts and ends at Etaples Military Cemetery.

The cemetery is – as those who have visited it can testify – a vast and (for its size) relatively rarely visited spot, being on the coast well away from the well-trodden battlefields of the Somme.

There are 10,771 Commonwealth burials of the First World War here, the earliest dating from May 1915. Only 35 of these burials are unidentified – which is due to the fact that most burials were from the large hospitals in the area, and men who were admitted to such hospitals were – generally – ‘known’.

The Commonwealth War Graves Commission says this about the location:

“…the area around Etaples was the scene of immense concentrations of Commonwealth reinforcement camps and hospitals. It was remote from attack, except from aircraft … In 1917, 100,000 troops were camped among the sand dunes and the hospitals, which included eleven general, one stationary, four Red Cross hospitals and a convalescent depot…”

The point that is made here about being remote from attack, apart from by aircraft is relevant as this acknowledges a series of air raids made in 1918. It is one raid on 19 May that is pertinent to this account.

If visiting the Etaples Military Cemetery, there are a number of ‘patterns’ that can be found among the headstones.

For instance in plots 1 and 2 we find the early (1915) casualties. In plot 1 the vast majority of the graves are of officers. In plot 28 again, the burials are almost entirely those of officers, whilst in plot 24 can be found nearly twenty burials of servicemen of the Jewish faith.

Because the burials were mainly of men who died in the hospitals, there are virtually no ‘patterns’ of men from a single unit who are grouped together. That is, however, until you arrive at plot 66.

In plot 66 (row C) are dozens of men all with the same ‘cap badge’ – that of the Life Guards.

A further meander among nearby graves will enable the visitor to find a few more that are located in plot 65 and 68. Virtually all of these record the same date of death – that of 19 May 1918. Counting these one gets to the figure of 38. In addition nine other men have dates of death of 20 May, two died on 21 May 1918, one on 3 June. Curiously one – Trooper Frederick Thomas – (according to the headstone) died on 20 June. Another is noted as having been killed on 15 May,[1] however both of these are errors which will be reported to the CWGC.

Not all the men in this group were seemingly 'badged' as 'Life Guards'. There are two men from the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons and one from the 3rd (King's Own) Hussars and another from the 3rd Dragoon Guards (Prince of Wales' Own). Another is from the Royal Horse Guards ('The Blues').

What is the story? A clue is the fact that nearby we have another set of individuals who all have the same headstone. A total of 32 men of the Canadian Army Medical Corps, and attached to the 1st Canadian General Hospital were killed on the dame day – 19 May 1918.

Again these men are all buried in plot 66.

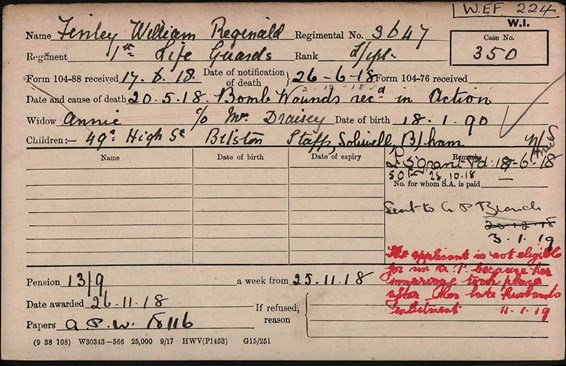

Inspecting the pension records of some of the men buried here is informative. The pension card for William Reginald Finley tells us he died due to ‘bomb wounds received in action’.

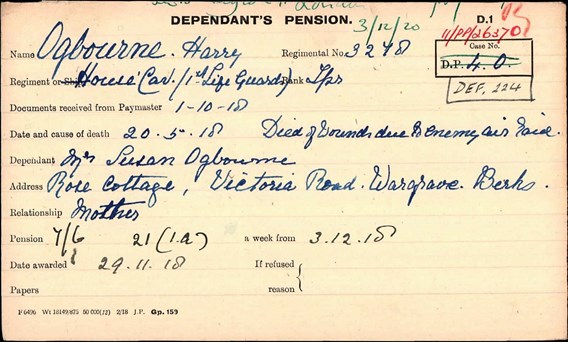

And Harry Ogbourne's pension card even more specifically 'died of wounds due to enemy air raid.'

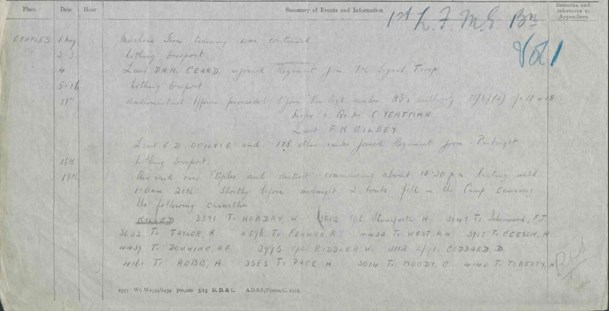

A download of the War Diary of the battalion is helpful. The National Archives holds, under reference WO 95/247/2, a copy of the war diary of the "1 (1st Life Guards) Battalion, Guards Machine Gun Regiment" for the period.

The unit’s adjutant gave the succinct ‘nothing to report’ for the days 5 to 16 May. On 17 May Major C Yeatman and Lt FN Gilbey joined the regiment, and – separately – Lt ED Ogilvie and 178 other ranks joined the regiment from Pirbright.

18 May was another ‘nothing to report’ entry, but on 19 May we have the following:

Air raid over Etaples and district commencing about 10.30pm lasting until 1am 20th [May]. Shortly before midnight two bombs fell in the camp causing the following casualties.

Very unusually, the diary then lists not only the dead but the wounded.

Above: One of the four pages of the war diary detailing the casualties due to the air raid.

Altogether 42 men are named as having been killed, with 83 listed as being wounded. Thirteen of these died of their wounds. Curiously, one man buried in this plot seems not to be named in the war diary – that is Lawrence Nelson of the Royal Horse Guards.

In the book 'Horse Guards' by Barney White-Spunner (ISBN-13:978-1-4050-5574-1) on page 484 there is an account of this which reads

"At about 11 p.m. a warning came that enemy planes were on the move over head, so lights were extinguished and we moved away to out tents... there was a blinding flash, and then silence, except for a groan here and there among the wreckage of the tents"

The accounts of these men - 56 in total - who were killed or died of their wounds have never been collected together but below we attempt to tell the stories of as many as possible.

The stories

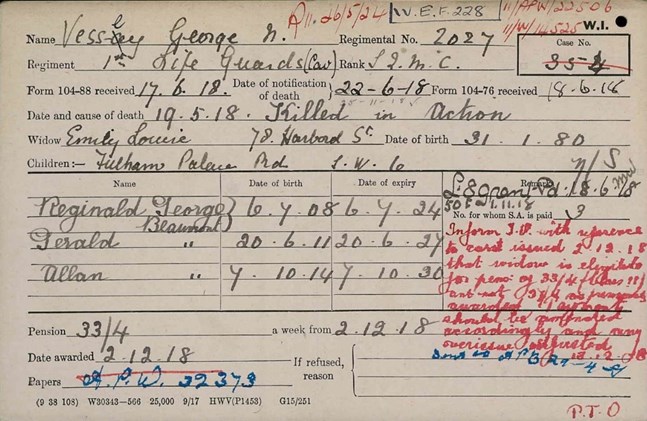

The oldest was 43 year old Squadron Quartermaster Corporal George Vessey whose family added the following when completing the form for the (then) Imperial War Graves Commission:

Long Service and Good Conduct Medal. Son of the late George Thomas Vessey, M.R.C.V.S., Lond., of Christchurch, and Mrs. Vessey, Bournemouth; husband of Emily L. Vessey, of 78, Harbord St., Fulham Palace Rd., London. His service with the 1st Life Guards, totalled 20 years and 8 months and included the South African War, and 2 years and 6 months in France. Instructor of Musketry, Sept., 1914, to Feb., 1916.

As can be seen on the card, George Vessey lived at 78 Harbord Street, Fulham

The other senior NCO was Squadron Corporal Major – (equivalent of Company Sergeant Major) Walter Webb who was born in 1881, making him 37 years old when he was killed. He was a veteran of the Boer War.

Above: Squadron Corporal Major Walter Webb.

Above: A coloured pre-war post-card showing two Corporal Majors in full ceremonial uniform. It's not impossible that one of these is Walter Webb

Walter Webb was born in Hurst on 29th December 1880 to Robert and Annie Webb and on January 17th 1882 he was christened in St. Nicholas Church, Hurst. He was the seventh of twelve children and had three brothers and eight sisters. His father came from Devon and was an Estate Agent at the time of Walter's birth.

Ten years later his father had become a Veterinary Surgeon and the family had moved to Lansdown Place, Twyford. Walter attended the Boys School in Reading but in April 1894 when he was thirteen, the family moved to Lea Farm, Hurst and Walter became a pupil at Hurst Boys School for his final year of education.

Walter enlisted in the army at Regents Park barracks on 21st June 1898 and signed up with the 1st Life Guards for twelve years. He gave his age as eighteen years six months, adding an extra year to qualify. Walter was over six feet tall, weighed 11 stones four pounds and had black hair, brown eyes and a dark complexion.

After service in the Boer War, Walter was stationed at Clewer Cavalry Barracks in Windsor and was soon promoted to Acting Corporal. Over the next five years Walter rose to the rank of Corporal of Horse. On 27th June 1909 he married Olive Sansum at Trinity Church, Windsor. Walter completed his 12 years of service in 1910 and immediately signed on to complete 21 years.

Wounded in October 1914 at the First Battle of Ypres, Walter was returned to the UK where he served for most of the remainder of the war, but was possibly one of the draft of men who joined the unit two days before the air raid.[2]

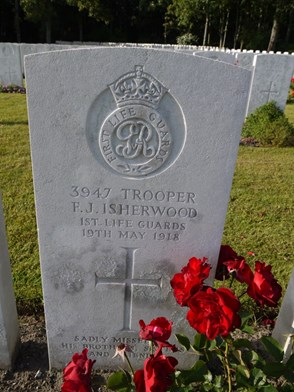

Two of the fatalities were nineteen years of age, being Troopers Richard West from Peterborough and Frederick Isherwood of Wood Green, London.

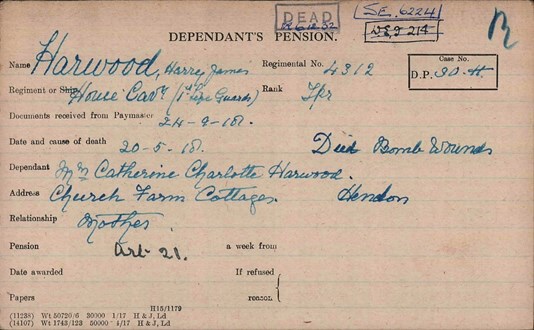

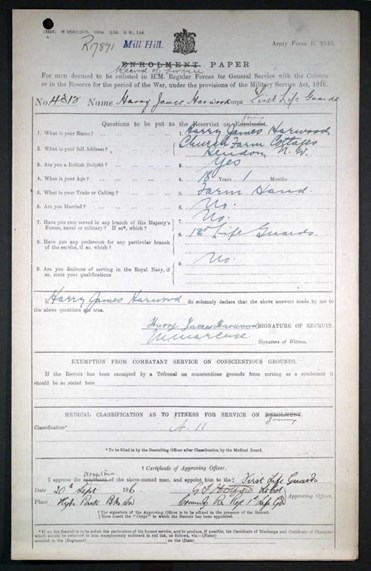

Another was just 18 years old. Harry Harwood (from Hendon) died of wounds – his Pension Record Card says ‘of bomb wounds’.

His attestation paper tells us he joined the regiment aged 18 years and 1 month on 20 September 1916.

Three of the men who were killed had been decorated – one was 35 year old Squadron Quartermaster Corporal Albert Horsman from Gomeldon, Wiltshire who has been awarded the (French) Medaille Militaire

Corporal of Horse (this rank is the equivalent to sergeant in other regiments) George Boylin had been awarded the (Belgian) Croix de Guerre (image below).

Corporal of Horse James Hamilton Fleming had been awarded the DCM.

De Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour, vol. 4 records:

“James Hamilton Fleming, D.C.M. Corporal of Horse, Life Guards, youngest son of David of The Shaws, Harwich Road, Colchester, by his wife Martha youngest daughter of Robert Spittal,, b Glasgow, co Lanark 6 May 1890; educated Cheetham Higher Elementary School, Manchester; enlisted in the 1st Life Guards 31 May 1910; served with the Expeditionary Forces in France and Flanders, and was killed in action during an enemy air raid at Etaples. His Commanding Officer, Captain and Adjutant C H Wyndham, wrote: “I cannot tell you what a loss he is to me. One could rely on him for anything, and in the recent machine gun course he came out among the best in the regiment. The company will not be the same without him. I shall never forget your son the day in 1914 when he got his D.C.M. (Nov 6th). The village of Klein Zillebeke, in Belgium, and adjacent trenches were attacked and taken by the enemy. The regiment was ordered to counter-attack and retake them, and incidentally to close the gap in the line. Your son displayed great spirit and leadership in this attack, and single-handed attempted to charge a German machine gun. He fell wounded a few yards from it.” He was awarded the D.C.M. for gallant and distinguished conduct in the field; unmarried”

Most of the men were from London and the Home Counties, but besides these 'Home Counties' men, there was a smattering of men from elsewhere in the UK, such as Harry Geeson, who (from his Pension Record Card) we learn was from 40 Rayleigh Street in Bradford

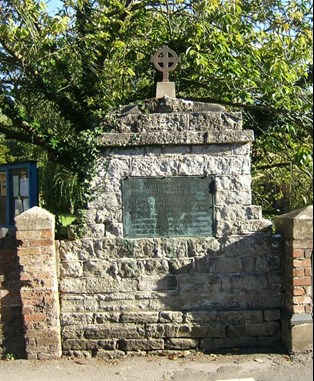

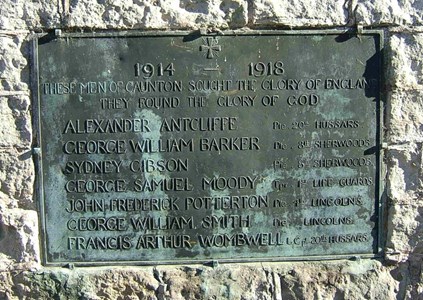

George Moody was from Farnsfield, Nottinghamshire and worked on his father's farm. He is listed on the village war memorial at Caunton

Above and below: The War Memorial outside St Andrew's Caunton. (Southwell and Nottingham Church History Project).

We have at least one from Dublin – Trooper Thomas De Renzy was from this city – his parents' address being Royal Veterinary College, Shelbourne Road, Ballsbridge, Dublin.

Above: This watercolour shows the old Veterinary Science School on Shelbourne Road in Ballsbridge, Dublin 4. Unfortunately this Victorian red brick structure was demolished in 2006. The current Veterinary School relocated to UCD’s Belfield Campus in 2002. (www.elizabethokane.com/painting-dublin-old-vet-school-ballsbridge).

The Pension Record for Thomas De Renzy tells us his brother Richard was killed in the Irish Guards on 12 September 1917. The brothers are named on panels inside St. Mary's Church, Haddington Road, Dublin.

Wilfred Riddler's friend was Sidney Webb and the following account relates to the two mates who joined up:

On 30 October 1915, aged 19, [Sidney] and a friend, a Wilfred (‘Billy’) Riddler whose family were living at 37 Thomas Street .... volunteered at Cirencester Recruiting Office to join the army and chose to join the Life Guards. They were almost immediately sent to the Knightsbridge Barracks in London where they underwent training in riding and military duties. Later they were stationed at Windsor for cavalry training and took part in ceremonial parades such as the opening of Parliament.[3]

We also have Trooper Roger Fenwick, who came from a well-to-do family from Plas Ffron, Wrexham. There is a special memorial plaque dedicated to Roger inside the Church (St Dunawd) at Bangor on Dee.[4] The inscription reads:

To the Glory of God

And in Proud and loving memory of

Roger Mansell William Fenwick 1st Lifeguards.

Youngest son of late

Cpt George Fenwick 23rd Royal Welsh Fusiliers

And Mrs Fenwick of Plas Fron Wrexham.

Born Feb 10th 1898

Killed in Air Raid in France May 19th 1918.

Buried at Etaples.

‘Beareth all things

Believeth all things

Endureth all things’

1st Corinthians 13th ch.

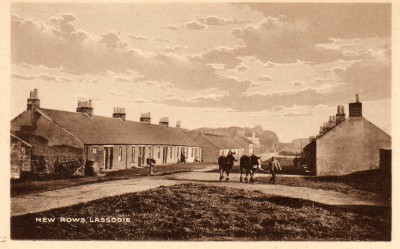

Another of the fatalities was 25 year old John Gray from New Rows, Lassodie in Scotland.

Above: John Gray (www.livesofthefirstworldwar.iwm.org.uk/lifestory/1428274)

One epitaph recorded by the CWGC is particularly poignant, this for Cecil Percival King, aged 23: "Son of Lot Fred and Agnes King, of 214, Holdenhurst Road, Bournemouth... He won many prizes as a long distance swimmer."

Other fatalities included Trooper Henry Toberty aged 32.

Above: Henry Toberty. Image via www.ww1cemeteries.com/etaples-roh-s-z.html and courtesy of Great Nephew Tom Toberty

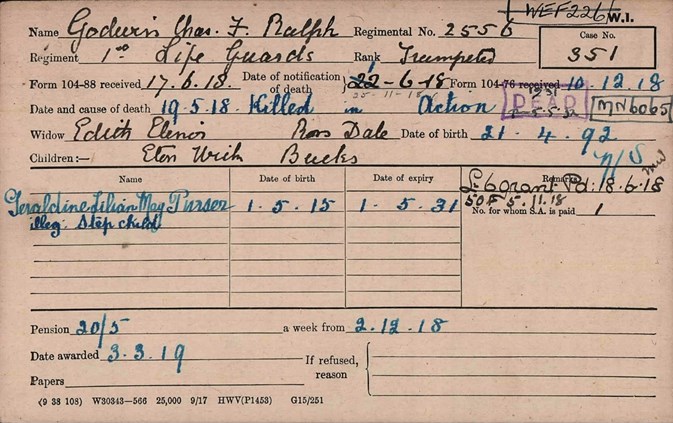

Charles Fountain Ralph Godwin (image below) of Eton Wick, Buckinghamshire, whose rank was 'Trumpeter' and who we discover from his pension card left behind a widow and step-child.

Eric Royce (aged 22) was destined for the priesthood, until war intervened. He has an entry in De Ruvigny’s Roll of Honour:

Eric Hooper Royce Trooper No 3609 Son of Mark Hubbard Royce of 14 Eccles Old Road and his wife Amelia Elizabeth Hooper daughter of Thomas Morgan Warren. Trooper Royce was born Eccles 17th May 1896. He was educated at Hulme Grammar School where he was continuing his studies with a view to becoming ordained. He enlisted 18th October 1914 and served with the Expeditionary Force in France and Flanders. He was killed in an enemy air raid at Etaples.He is buried in Etaples Cemetery. Trooper Royce was a keen sportsman and gained his cap at Hulme Grammar School for cricket and lacrosse.

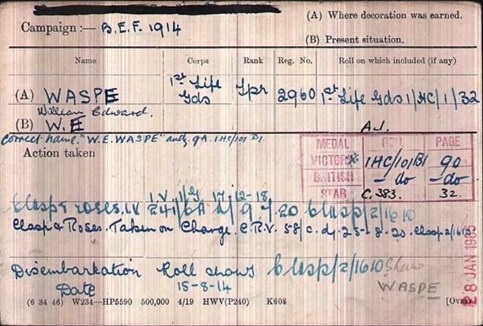

Another of the fatalities was Corporal of Horse William Edward Waspe from Stretton-under-Fosse.

Above: William Edward Waspe (www.livesofthefirstworldwar.iwm.org.uk/lifestory/4637197)

Above: The Medal Index Card for William Waspe

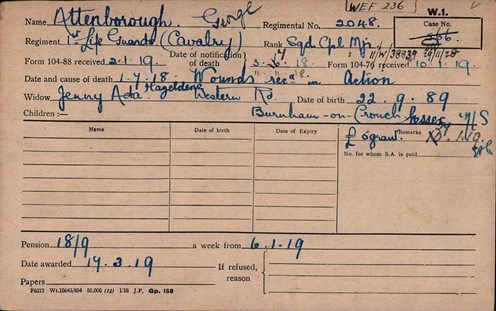

The men who died from this bombing are not just buried in Etaples - at least one perished at home, being Squadron Corporal Major George Attenborough who died of wounds on 1 July 1918.

George is buried at Burnham-on-Crouch.

There is also - possibly - Trooper William Charles Phillips who died on 9 July 1918 and is buried at St John the Baptist Church, Moordown (near Bournemouth).

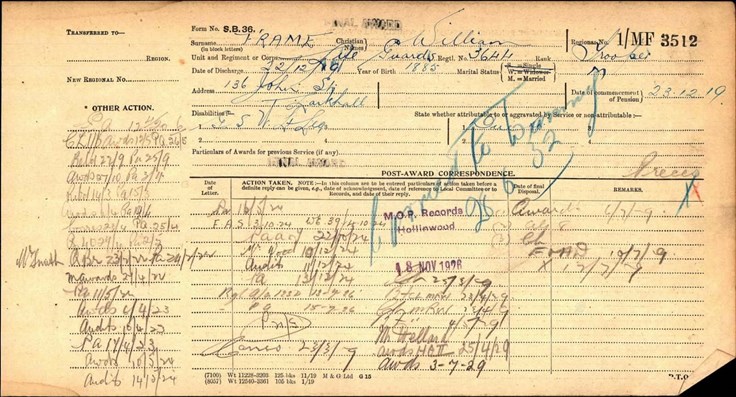

Other men - as outlined above - sustained injuries. One example being Trooper William Frame, whose wounds can be seen on the Pension Ledger below.

The Life Guards - their earlier war service

The 1st Life Guards were, at the time of the bombing, converting from their role as cavalry. Prior to this, they had served in a more traditional role (albeit 'dismounted' for most of the war).

Up to August 1914, the Life Guards were stationed at barracks in Hyde Park, handily placed for the many royal guard and ceremonial duties that they were called upon to perform in London. However, despite the finery, this prestigious regiment, soon after the declaration of war, had one of the squadrons detached.

The peacetime establishment in the United Kingdom was 19 cavalry regiments including three regiments of the Household Cavalry.

A total of 16 regular cavalry regiments were earmarked for overseas service, with a 17th regiment provided by a composite regiment (this was 'The Household Cavalry Composite Regiment') which formed with a squadron from each of the three Household Cavalry regiments – the 1st Life Guards, the 2nd Life Guards, and the Royal Horse Guards. On mobilisation this Composite regiment moved to France with 4th Cavalry Brigade and saw action at Mons.

The composite regiment was also involved in the retreat of September 1914, the decisive battle of the Marne, and later at First Ypres. The Composite Regiment was broken up on 11 November 1914, and the squadron of the 1st Life Guards that had been detached to form this unit rejoined the 'parent' regiment, which was by now itself on the Western Front.

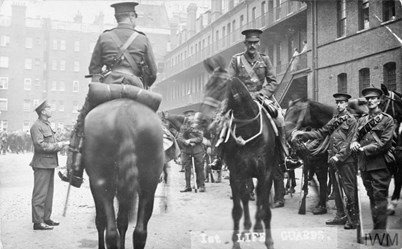

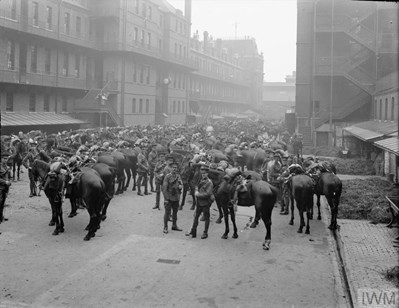

Above: A dismounted cavalry draft of the 1st Life Guards. (IWM Q 66196)

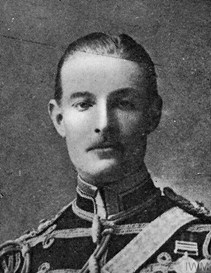

Above: Lieutenant Colonel E B Cook MVO, officer commanding the 1st Life Guards, mounted on his horse, preparing to leave with the advance party for France. (IWM Q 71673)

Above: The 1st Life Guards parading before leaving for France. (IWM Q 66223)

Above: A mounted cavalry draft of the 1st Life Guards with Captain Gerrard Leigh in the foreground. (IWM Q 66190)

Above: 1st Life Guards at Knightsbridge Barracks. (IWM Q 71661)

Above (IWM Q 71664) and below (IWM Q 71663): The first contingent of 1st Life Guards ready to leave Knightsbridge Barracks for the War.

Above: A British cavalryman eating beside his horse. Belgium, 13 October 1914.(IWM Q 53324)

Meanwhile, the main body of the regiment crossed the channel to Belgium, landing on 8 October 1914. Other than in the first two weeks when it was used in the traditional cavalry, for mobile reconnaissance, it fought most of the war as a dismounted force.

The regiment was involved at the First Battle of Ypres in October and November 1914 (losing 44 officers and killed in action men in this period including 24 in a three day period between 28 October and 1 November). It was in this period that the regiment lost Major Rt. Hon. Lord John Spencer Cavendish, DSO.

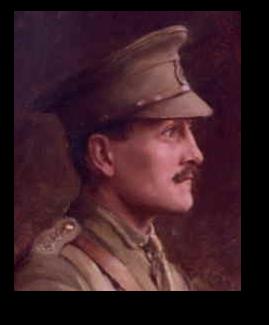

Above: Major Rt. Hon. Lord John Spencer Cavendish, DSO

Shortly after the death of Lord Cavendish, the regiment also lost Lt Richard Levinge, 10th Bart.

Above: Lt Richard Levinge

At the height of 1st Ypres, the commander of C Squadron Captain Lord Hugh William Grosvenor (who was a son of Hugh Grosvenor, 1st Duke of Westminster) was killed. He sent a message back to his headquarters:

'There appears to be a considerable force of the enemy to my front and to my right front. They approach to within about seven hundred yards at night. Our shells have not been near them on this flank'

Above: Captain Lord Hugh William Grosvenor killed 30 October 1914

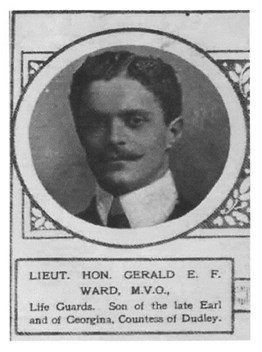

Also killed on this day was Lt The Hon. Gerald Ernest Francis Ward, son of the 1st Earl of Dudley

Other deaths at this time included Lt The Hon William Reginald Wyndham (aged 38) and 2/Lt Howard St George both of whom are buried at the ‘aristocrats’ churchyard at Zillebeke.

The regiment was also involved in the Second Battle of Ypres (April-May 1915 when they suffered 26 deaths – of these 20 were incurred on 13 May), and were, later in the war, involved in and the Battle of Loos in September and October 1915 and at Arras in April 1917.

However between January 1916 and the end of December 1917, they lost ‘only’ 34 officers and men, some of these deaths occurring in the UK.

On 10 March 1918, the regiment was detached from 7th Cavalry Brigade, with which it had served from August 1914. It was formally dismounted and converted into the No 1 (1st Life Guards) Battalion of the Guards Machine Gun Regiment.

It was during the regiment's training and conversion to a machine gun battalion that it was hit by the German raid of 19 May.

The regiment only lost six further soldiers ‘in action’ after the 19 May air raid, (the CWGC records five of these as being in the Guards Machine Gun Regiment (1st Battalion) and the other in the 1st Life Guards).

Above: Guards Machine Gun Regiment badge.

Rarely can one unit have suffered disproportionate fatalities on one day compared to the rest of its active service.

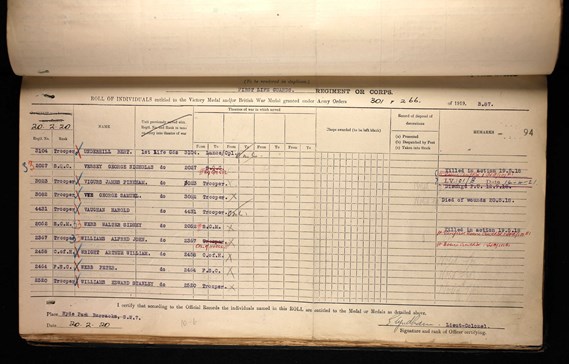

Going through the pages of the Medal Roll (an example of which appears below) it is apparent how the 19 May bombing accounted for such a large proportion of men.

Article by David Tattersfield, Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association

[1] This is Trooper Page, although the headstone correctly says 19 May.

[2] www.warmemorial.org.uk/ww1?p=36

[3] www.cirenhistory.org.uk/ww1_pollard_ridler.htm#xl_ww1_riddler_wilfred

[4] www.flintshirewarmemorials.com/memorials/bangor-on-dee-memorial/bangor-on-dee-soldiers/roger-mansel-william-fenwick/