Frontline or Field ambulance? Where were Chaplains best placed to help?

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Frontline or Field ambulance? Where were Chaplains best placed to help?

On 25th April 1915 Father William Joseph Finn became the first British military chaplain to be killed in action in the First World War. His death ignited a debate that continues to resonate with chaplains who serve the Armed Forces in the present day – where are they best placed to help?

Above: Father William Finn and the cemetery at V Beach at Gallipoli in which he was buried

Father Finn had requested permission from the officer commanding his battalion (the 1st Royal Dublin Fusiliers)to be allowed to land on V Beach at Gallipoli with the first wave of the expeditionary force. His officer was said to be extremely reluctant, but finally succumbed to Finn's insistence that the place for a Roman Catholic chaplain was beside the dying where he could provide absolution.

The landing at V Beach was to prove catastrophic. Father Finn was hit almost immediately after reaching the beach, with some reports stating that he was killed instantly and others claiming that he managed to provide absolution to a few of the men around him before passing himself.

Finn was clearly a brave man, but his story raised an important point: if he had listened to his CO he would still have been alive and in a position to continue offering pastoral care to the men under his charge in the difficult times ahead.

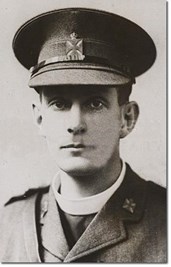

It was a theme picked up in the diaries of the Anglican chaplain Revered Oswin Creighton, who had also been part of the same 29th Division (Regular Army) landings at Gallipoli. Unlike Finn, Creighton had followed orders and not attempted to go ashore with the first wave.

Above: Revered Oswin Creighton

Creighton wrote: “I saw the senior chaplain of the Division just before we left... his orders are that the chaplains are in no case to go in front of the advanced dressing station. He says they are always anxious to get up to the front, where they can only be of use at one point in the line.”

He added: “The chaplain is a non-combatant and surely it must be wrong for him to go out in the attack, much though he may hate not to share the danger of his men to the full.”

Nevertheless, he acknowledged the attraction, conceding that Father Finn’s death was an example of “the extraordinary hold a chaplain can have on the affections of his men if he absolutely becomes one of them and shares their danger”.

Above: Rev Creighton’s memoir and diary of his time at Gallipoli and the actions of Father Finn make for interesting reading.

Here-in lay one of the greatest dilemmas faced by chaplains of all faiths: if they were to really make a spiritual connection with the men they needed to win their respect as fellow ‘men’. One senior chaplain, Father Henry Gill, was no doubt echoing the thoughts of many of his counterparts when he wrote in his diary: “I thought it worth the risk to pay a visit to the most advanced line of trenches in order that my influence with the men might be greater. I know that this had excellent results.”

Sometimes front-line service for the chaplains was clearly about winning respect from their peers and the need to prove themselves as 'real men'. However, matters were undoubtedly more complicated for the Roman Catholics who, like Father Finn, often felt that the soldiers of their faith had a right to expect the last rights and absolution.

As a result of this pressure, there were more Roman Catholic chaplains successfully breaking an official ruling in the first two years of the war to not go beyond the Advanced Dressing Station, which in turn fed a popular – and unjust–narrative that they were braver than their counterparts of other faiths.

Among those who helped propagate this myth were the likes of Robert Graves, who wrote of the Anglican chaplains: “...had (they) shown one-tenth of the courage, endurance and other human qualities that regimental doctors showed, the British Expeditionary Force might well have started a religious revival. But they had not, being under orders to avoid the fighting. Soldiers could hardly respect a chaplain who obeyed these orders, and not yet one in 50 seemed sorry to obey them... the Roman Catholic chaplains were not only permitted to visit posts of danger but definitely enjoyed to be where the fighting was, so that they could give extreme unction to the dying.”

Many Anglicans had also broken the rules, and as soon as they were relaxed they were as often found in the front-line trenches as the Catholics, but this was not enough to alter the view of the likes of Graves.

Perhaps this is why one high profile and senior Anglican Chaplain, Rev Studdert-Kennedy (better known to many as ‘Woodbine Willy’), always told new Church of England chaplains arriving in France that they should make a point of working in the front areas. He is even quoted as having said: “The more padres die doing Christ-like deeds, the better for the church.”

The fatality figures certainly speak for themselves.

It is recorded that 179 British Army Chaplains died in the war, with the fatalities broken down by denomination as follows: 98 Anglicans, 34 Roman Catholics, 12 United Board, 11 Presbytarian, 10 Wesleyan, 1 Salvation Army. (Note: These statistics only account for 166 deaths - the missing 13 are the subject of ongoing research.)

There were far more Anglican chaplains serving than those of any other faith, with the Catholics accounting for the next largest number. In proportionate terms, the death toll is evenly spread.

Furthermore, if medals are seen as a marker of front-line presence or ‘bravery’, the perception of Anglican inferiority is again proved wrong: all three of the Victoria Crosses presented to military chaplains were to Anglicans.

Above: Reverend Edward Mellish, Rev William Addison and Rev Theodore Bayley Hardy. All three were all presented with the VC for their work in bringing in wounded under enemy fire. Mellish at Ypres in 1916, Addison at Kut, Mesopotamia, in the same year, and Hardy on the Somme in 1918.

Graves might also have been surprised to discover that the whole issue was not so clear cut among the Catholic establishment as he suggested - “What we want is that chaplains will be permitted to go to the front... so that when the poor fellow drops he may have a priest beside him,” said Cardinal Logue of Ireland in October 1914, in stark contrast to leading Catholic newspaper The Tablet, which reported from a chaplain who had been at the front “from the first” who claimed that when advances were made the casualties were far too spread out for one man to try and administer to them all.

“The question was how we could be of greatest use to the greatest number of men. It followed that if three regiments were in an attack, being with any one of the three would make it impossible to do anything with the other two,” wrote the Anglican Rev Creighton after the death of Father Finn at Gallipoli in 1915.

Creighton was clearly an advocate of the official line: that the best place to be situated was at a point where the majority of the wounded would be taken.

As a result, most chaplains would station themselves either one step behind the front-line at the Regimental Aid Post (the most advanced Red Cross position where the wounded were first brought in by the stretcher bearers) or at a point further back - the next two stops on the journey of the wounded being the Advanced Dressing Station followed by the Casualty Clearing Station; the latter usually in a far less vulnerable position in terms of the reach of the enemy guns.

Above: A Casualty Clearing Station

Arguments could be made about the value of each, but it is hard to question the sense of the chaplains being at an aid post rather than going ‘over the top’ with an advance. The argument is underlined by the very different sacrifices made by two Catholic chaplains, Fathers O’Sullivan and Gray, during the Battle of the Somme in 1916.

Gray stationed himself at an Advanced Dressing Station and later wrote: “The place was a shambles, full of wounded, with stretcher cases lying in the open outside, and all through the night the stream of stricken humanity flowed unceasingly.” He spent four days and nights dressing the wounded and providing spiritual comfort until, not having had any sleep in the whole period, he finally succumbed to exhaustion and “hysteria”.

In stark contrast, Father O'Sullivan wanted to advance with his flock. After being initially refused, like Father Finn at Gallipoli, he finally managed to persuade his commanding officer that it was a necessity for him to be on hand to provide sacraments to the dying. O'Sullivan was subsequently killed soon after going ‘over the top’ by enemy shell fire.

One of the most experienced military chaplains of the war was Father Stephen Rawlinson, who had been one of the first Catholic priests to volunteer for overseas service and subsequently seen front-line action in the initial engagements faced by the British Expeditionary Force on the Western Front. By 1916 he had been promoted to the rank of Assistant Principal Chaplain for all religious denominations on the Western Front. In 1918 Father Rawlinson issued new guidelines, stating that a chaplain “should remember that one live chaplain is worth more than 50 dead ones”.

Above: Sacred Heart church in Hull is a memorial to Father Finn.

As for Father Finn, his memory lives on at The Sacred Heart church in Hull, Yorkshire, which was built in the 1920s and paid for by his brother, Councillor Frank Finn, Lord Mayor of Hull, as a memorial.

Article by Dr Martin Purdy

Martin wrote a thesis for his MA (by Research) on the topic of First World War military chaplains in 2012. Click here to download it for free