The Tragic Story of 2/Lt Stewart Ridley

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Tragic Story of 2/Lt Stewart Ridley

'He spent his dear boy’s life for England'

Engine failure was a persistent hazard for fliers during the Great War, often with fatal consequences. Here we have the story of a gallant young airman who met his end in a dreadful way due to a malfunctioning engine.

Stewart Ridley was born on 6 July 1896, the second son of Mr and Mrs T. W. Ridley of Willimoteswick, in Redcar, North Yorkshire, and the younger brother of Thomas Kenneth George Ridley.

The family lineage included Bishop Nicholas Ridley, a Chaplain to Henry VIII, and later the Bishop of London under Edward VI, before being burned at the stake at Oxford in 1555 during Mary I’s persecution of Protestants.

His parents’ house owed its unusual name to the family’s former home in Willimoteswick Castle in Northumbria, birthplace of the martyred Bishop.

Stewart was educated at Mr J. Stewart’s Preparatory School at Harrogate and, from 1910, at Oundle School in Northamptonshire. The school was founded in 1556 and has always been maintained by the London Worshipful Company of Grocers; the motto is God Grant Grace. Stewart was a member of the Officer Training Corps and a keen Rugby player, where he was selected for the First XV, which included playing in the team’s last peacetime match, against the School Old Boys, in November 1913.

He left Oundle in April 1914, and prepared for a career in business. However, in August 1914 Britain declared War against Germany, and Stewart’s embryo business career ended, when he and brother Thomas both enlisted in the 1/4th Battalion of Alexandra, Princess of Wales’s Own (Yorkshire Regiment) – the Green Howards – then forming at Northallerton in the York and Durham Brigade, Northumberland Division. The Regiment’s name dated back to the Wars of the Austrian Succession in the mid-18th Century, when regiments were usually called by the name of their Colonel. When two regiments led by a Colonel Howard were brigaded together, they were distinguished by the colour of the facings on their scarlet uniforms: the Buff Howards became the Royal East Kent Regiment, popularly known as The Buffs, and the Green Howards became the Yorkshire Regiment.

Stewart did not stay long with the 1/4th Yorkshires, as he was commissioned as Second Lieutenant in the 12th (Service) Battalion of the Regiment (Teesside Pioneers) in February 1915. His new unit was formed in December 1914 by the Mayor and Town of Middlesbrough, and based at Gosforth.

The Aerial Department of Sir W.G. Armstrong Whitworth & Co. Ltd. had established an aeroplane works at Gosforth in 1913, and when Stewart arrived there the company was building B.E.2s under contract. It is by no means unlikely that Stewart saw the aeroplanes in flight, and this may have influenced his July decision to apply for a transfer to the Royal Flying Corps (R.F.C.) which saw him serve as an Observer on the Western Front. He was duly gazetted as a Flying Officer (Observer) on 22 November 1915.

Stewart’s older brother Thomas briefly transferred to the R.F.C., and was gazetted as a Flying Officer (Observer) on 21 November 1915, before a posting to No. 26 Squadron1, a unit formed in October with many South Africans, destined for service in East Africa. However, Thomas returned to the 1/4th Yorkshires, where he was promoted to Captain, and appointed as the battalion Adjutant, in February 1916. He served with the Yorkshires for the rest of the War, and was awarded the Military Cross without citation in the 1919 King’s Birthday Honours List. After the Armistice he transferred to the 17th Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment before relinquishing his commission in July 1920. He later re-joined the Yorkshire Regiment and was promoted to Major in 1930 and then Lieutenant-Colonel in 1937, when he became the regiment’s commanding officer. During the 1939-1945 War he commanded the Middlesbrough Garrison, charged with the defence of Teesside, for which service he earned an Order of the British Empire in 1942. Appointment as Deputy Lieutenant of the North Riding of Yorkshire came in 1945. He died in 1954.

Following Stewart’s time in France as an Observer, he returned to the U.K. for pilot training at the Hall School at Hendon, where he was instructed by Cecil Mckenzie Hill2 and Harry Frederick Stevens3, using Hall and Caudron aeroplanes. Founded in 1913, by 1915 the School claimed that its four Hall biplanes made it the best equipped tractor [aircraft] school in England. For Stewart, late 1915 was not a good time for flying instruction, with the week of 10-17 December being assessed as “bad as it could well be for tuition work”.

On 10 February 1916, in its news column about British flying schools, Flight reported:

The following pupils should shortly go for their certificates: Redford, Ridley, Nicolle, Evans, and Sepulchre.

Two weeks later, the 24 February Flight included:

Mr. Ridley flew for his certificate on Sunday, and passed all the tests in excellent style.

Oddly, Stewart qualified for Royal Aero Club Certificate No. 2374 on 26 January.

On 23 March 1916 Stewart, who enjoyed the nickname 'Riddles' was initially posted to No. 34 Squadron at Castle Bromwich4. However, 2Lt. Ridley’s time with the unit was brief. On 25 April he was gazetted as a Flying Officer (Pilot), and shortly afterwards transferred to No. 17 Squadron in Egypt. The squadron had been formed at Gosport (Fort Grange) on 1 February 1915 before moving to Hounslow on 5 August prior to embarkation for Egypt on 15 November, equipped with the B.E.2c. After arrival at Alexandria on 11 December, it moved to Heliopolis a week later, before being split into components and deployed to separate aerodromes: El Hamman, Suez, Kharga, and Port Sudan, with detachments at Fayoum, Minya, Assiyat, Rahad, Nahud and Jebel el Hillah. The squadron’s aeroplanes were in Egypt to support the troops defending the Suez Canal from the Turks in the east, and those suppressing the Senussi Revolt in the west.

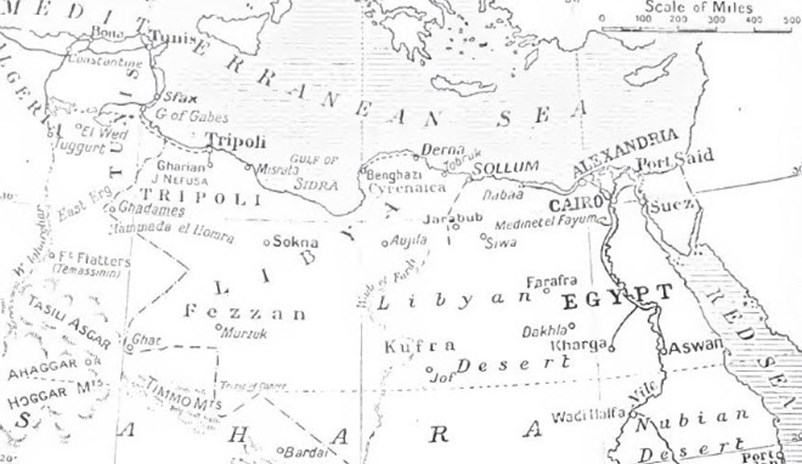

The Senussi was an Islamic sect based in Libya and Egypt, and had waged a guerrilla campaign against the Italian colonial power after the Italians displaced the Ottoman Turks following the Italo-Turkish War of 1911-19125. As part of an effort to divert British troops away from the major fronts, the Central Powers encouraged the Grand Senussi, Ahmed Sharif es Senussi, to declare a Jihad against the infidels. Boosted by artillery, machine-guns and funds supplied by German U-Boats6 , together with guidance from Turkish officers, including Yüzbaşi (Captain) Nuri Killigil7, the half-brother of the Ottoman Minister of War, Enver Pasha, the Senussi attacked British and Egyptian outposts in November 1915, and advanced to a position some 50 kilometres east of Sollum. In response, the Western Frontier Force (W.F.F.) was created, using British and Australian cavalry, British, Indian and South African infantry, with British and Egyptian artillery, as well as the Duke of Westminster’s armoured cars8. R.F.C. air support was initially provided by No. 14 Squadron.

Operations against the Senussi were divided in to two areas, in the north adjacent to the coast and, further south, around several desert oases. On 25 February 1916 the Senussi attacked along the coast, but were driven off. Next day, at Agagia, the W.F.F. cavalry, the Dorset Yeomanry, aided by the Duke of Westminster’s Rolls-Royce armoured cars, cut off the Senussi’s line of retreat, then the infantry advanced, forcing the tribesman to retreat, when the cavalry attacked. The battle broke the Senussi command, and although the campaign spluttered along for more several more months, the tribe was no longer a threat near the Mediterranean coast. However, the campaign against the Senussi around the oases in the south continued, while No. 14 Squadron was replaced by No. 17 Squadron.

Stewart joined a Half Flight from No. 17 Squadron at Kharga, some 520 kilometres south of Cairo, and over 160 kilometres from the nearest railhead. Situated in a hollow, Kharga was a well-watered oasis, with several nearby villages, and noted for its fine dates. The Half Flight had moved up from Assiyat on 20 April. Ground patrolling in the area was primarily the responsibility of No. 10 Company of the Imperial Camel Corps9 (I.C.C.), commanded by Lt. Charles Harry Norman Ashlin10 (formerly 1/1st East Riding of Yorkshire Yeomanry) who were based around a stone building, converted into a fort, that commanded the western approach to Kharga. A platoon of the 1/6th Battalion, Royal Scots provided the fort’s garrison. Lt. Ashlin had earned the displeasure of the Scots when he forbade the playing of bagpipes within half a kilometre of the fort, after the camels stampeded and raced into the desert when they first heard the sound of the instruments. Recovering the animals took several hours.

The next step in the campaign was to attack the Senussi encampment at Dahkla [also known as Dakhilah] oasis, some 160 kilometres to the west, which meant traversing an inhospitable desert, with few waterholes, before climbing the only path to the top of an almost perpendicular escarpment over 100 metres high. The airmen may well have considered themselves lucky to be able to fly over this most unwelcoming land.

Above: A Royal Aircraft Factory BE2c aircraft of the Royal Flying Corps flying over the desert near Belah (c.1918). (AWM B01937)

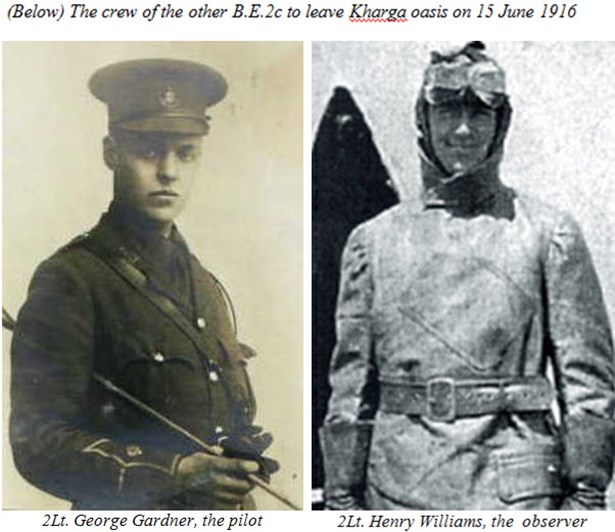

On Thursday 15 June two B.E.2c aircraft (the aircraft serial numbers appear to be lost to history) left Kharga for an advanced landing ground established by an I.C.C. patrol some 65 kilometres to the west, with the intention of carrying out a reconnaissance of Senussi positions next day. 2Lt. Ridley flew one aeroplane, with No. 3711 Air Mechanic Class 1 John Albert Garside, the son of James and Sarah Garside of Lowestoft, as observer. The other B.E. was flown by Lt. George Dudley Gardner 11 (formerly 2/4th Battalion, Yorkshire Regiment), and the observer was Gallipoli veteran Lt. Henry Daniel Williams12 (formerly 11th Squadron, Auckland Mounted Rifles), from Taranaki, New Zealand. Lt. George Gardner qualified for Royal Aero Club Certificate No. 1630 flying a Maurice Farman on 7 August 1915, at No. 5 Reserve Aeroplane Squadron at Castle Bromwich. He was originally posted to No. 24 Squadron, before a transfer to No. 17 Squadron at Heliopolis, Egypt, on 21 February 1916.

Events did not go to plan, as the airmen were unable to find the camel patrol, despite flying for about 90 minutes – the camels should have been found after an hour’s flight. As darkness was approaching, and Stewart’s engine was now not running as well as it should, the two aircraft landed and the crews set up camp for the night. Friday was not a good day for flying, but it was eventually decided that Stewart would take off and endeavour to locate the camels. However, the recalcitrant engine refused to start.

After consideration, it was decided that the best course of action would be for Lt. Gardner to return to Kharga to determine the exact location of the target oasis and to summon assistance, while 2Lt. Ridley and AM Garside remained with their stricken machine, supplied with the water and provisions from both aircraft. However, after the other aeroplane departed, they were evidently able to coax their engine back into life, and opted to fly back to Kharga. Tragically, after take-off, the B.E.’s engine failed again, and the airmen were again forced to land in the desert, now away from the position where searchers would expect to find them.

When Lt. Gardner arrived at Kharga, he learned that the I.C.C. patrol had returned. A search for the missing aeroplane commenced on Saturday, using the other B.E.2c in the air, accompanied by camels and motor cars on the ground. Of course, the airmen were no longer where they had originally landed, which made finding them much more difficult.

On Sunday afternoon, searchers found the second landing spot, some 40 kilometres from the original, but the aeroplane was no longer there. The airmen had evidentially tried to lighten the aeroplane’s load by abandoning non-essential items, but there was no information to guide searchers. The aeroplane was eventually found by a motor patrol on Tuesday afternoon; footprints in the sand showed that the men had started walking away. Fresh camel tracks were then discovered, and it was hoped that perhaps the aviators had been captured by Senussi. Sadly, shortly afterwards the I.C.C. found the airmen’s bodies. It was determined that 2Lt. Ridley died from a self-inflicted gunshot wound, probably from his revolver, at about 10.30 on Sunday, while AM Garside had perished later from dehydration. The officer leading the search party concluded that Stewart had taken his own life so as to improve his observer’s chances of survival.

When the bodies were examined, it was discovered that AM Garside had kept a diary of their ordeal:

Friday.—Mr. Gardiner (sic) left for Meheriq [El-Mahiriq is an oasis about 20 kilometres north of Kharga] and said he would come and pick one of us up. After he went we tried to get the machine going, and succeeded in flying for about 25 minutes. Engine then gave out. We tinkered engine up again, succeeded in flying about 5 miles [8 kilometres] next day (Saturday), but engine ran short of petrol.

Sunday.—After trying to get engine started, but could not manage it owing to weakness, water running short—only half a bottle—Mr. Ridley suggested walking up to the hills.

Six p.m. (Sunday): Found it was further than we thought; got there eventually; very done up. No luck. Walked back; hardly any water, about a spoonful. Mr. Ridley shot himself at 10.30 on Sunday whilst my back was turned. No water all day; don't know how to go on; got one Very light; dozed all day, feeling very weak; wish someone would come; cannot last much longer.

Monday.—Thought of water in compass, got half bottle; seems to be some kind of spirit. Can last another day. Fired Lewis gun, about four rounds; shall fire my Very light to-night; last hope without machine comes. Could last days if had water.

On Sunday 25 June a party, including a Chaplain, went out to the scene of the tragedy and buried the two airmen in the desert, before erecting a cross with their names on it over the heap of stones covering the bodies.

2Lt. S. G. Ridley is now buried in Grave H. 121 in Cairo War Memorial Cemetery, Egypt. AM J.A. Garside is buried next to him in Grave H.120.

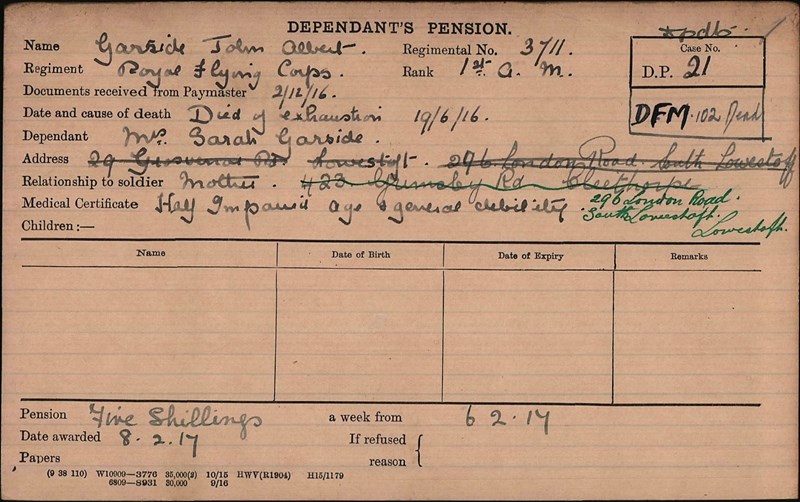

Above: The Pension Record Card for John Garside, which states he died of 'exhaustion'.

The cross originally erected over the airmen’s graves was recovered when the bodies were re-buried after the War, and is now in St Peter’s Church, Redcar, North Yorkshire. A monument in the St Peter’s Church grounds has this inscription:

Above: The Cross and two plaques at St Peter’s Church, Redcar

Above and below: The detail on the two plaques.

THIS CROSS, ORIGINALLY ERECTED INTHE LIBYAN DESERT, WAS SENT HOME ON THE REBURIAL OF THE BODIES AT MINIA AND PLACED HERE ABOVE THE PREVIOUSLY ERECTED MEMORIAL TO STEWART GORDON RIDLEY.

2ND LIEUT S G RIDLEY RFC 18TH JUNE 1916, 1ST AM J S GARSIDE RFC 20TH JUNE 1916

2ND LIEUT STEWART GORDON RIDLEY, YORKS REGT AND RFC B 6TH JULY 1896 AND DIED LIBYAN DESERT 18TH JUNE 1916

ERECTED BY COMRADES, OFFICERS AND SOLDIERS IN THE YORKSHIRE REGIMENT

The poet and dramatist John Drinkwater (1882-1937) was inspired to write a poem about Stewart, which appeared in the magazine of Laxton Grammar, another Oundle school, in his 1916 collection titled Olton Pools:

Riddles – R.F.C.

He was a boy of April beauty: one

Who had not tried the world: who while the sun

Flamed yet upon the Eastern sky, was done.

Time would have brought him in her patient ways –

So his beauty spoke – to prosperous days,

To fullness of authority and praise.

He would not wait so long. A boy, he spent

His dear boy’s life for England. Be content:

No honour of age had been more excellent.

References

1916 (Keith Jeffery ISBN 9781408834329)

1/4th Battalion, Yorkshire Regiment (www.4thyorkshires.com)

Air War 1914-1918 (www.airwar19141918.wordpress.com)

Airmen Died in the Great War (Chris Hobson ISBN 0 871505 81 X)

British Aeroplanes 1914-1918 (J. M. Bruce Putnam & Co, 1969)

British Aviation Squadron Markings of World War I (Les Rogers ISBN 0 7643 1284 7)

Cross & Cockade International (Various ISSN 1360 9009)

Epitaphs of the Great War (www.epitaphsofthe greatwar.com)

Imperial Camel Corps (Geoffrey Inchbald ISBN 0853070946)

John Drinkwater (https://allpoetry.com/John-Drinkwater)

Oundle School Website (www.oundleschool.org.uk )

Over the Balkans and South Russia (H. A. Jones Naval & Military reprint)

North Yorkshire War Memorials (www.ww1-yorkshire.org.uk)

RAF Squadrons (Wg. Cdr. C. G. Jefford ISBN 1 84037 141 2)

RFC Website (www.airhistory.org.uk )

Royal Flying Corps (Military Wing): Casualties and Honours During the War of 1914-1917 (Capt. G. L. Campbell http://access.bl.uk)

The Great War Forum (http://1914-1918.invisionzone.com/forums)

The Sky Their Battlefield II (Trevor Henshaw ISBN 978 0 9929771 8)

The War in the Air (H. A. Jones Naval & Military reprint)

Wings Over Cambridge (www.cambridgeairforce.org.nz)

Notes

1. No. 26 (South Africa) Squadron was formed at Netheravon on 8 October 1915, mainly from personnel who had served in the South African Aviation Corps in German South West Africa until the German surrender at Otavifontein on 9 July. It moved to East Africa, to operate B.E.2cs and Henri Farmans against the German forces led by Oberst Paul von Lettow-Vorbeck.

2. Mr C.M. Hill qualified for Royal Aero Club Certificate No. 1286 on 30 May 1915. He moved to New Zealand in May 1917 to be the Instructor at the flying school at Sockburn, near Christchurch, established by Henry F. Wigram (later Sir Henry Wigram). He was killed while flying a locally-designed Canterbury Aviation Company biplane in an aerobatic display at Riccarton racecourse on 1 February 1919. The accident, apparently due to structural failure during a loop, was first aeroplane-related fatality in New Zealand. [I am indebted to Society Member Errol Martyn for providing information on the accident.]

3. Mr. H.F. Stevens qualified for Royal Aero Club Certificate No. 1204 on 30 April 1915. He proved such an adept pupil during instruction that he was retained by the Hall Flying School as an instructor.

4. Equipped with the B.E.2c, No. 34 Squadron was formed from No. 19 Squadron on 26 January 1916; it would proceed to France in July. After re-equipment with the R.E.8, the squadron was despatched to the Italian Front in November 1917, and remained there for the remainder of the War.

5. The Italo-Turkish War saw several developments with respect to aviation history. On 23 October 1911, Capitano Carlo Piazza flew over Turkish positions – the world’s first aerial reconnaissance flight - and on 1 November Sottotenente Guilio Gavotti, dropped a bomb on Turkish troops from a German-built Etrich Taube. The Turks were the first to bring down an enemy aircraft by rifle fire when Tenente Manzini’s machine was shot down on 25 August 1912. On 10 September 1912 Capitano Moizo was the pilot of the first aeroplane to be captured by an opposing force.

6. One of the submarines that supplied weapons to the Senussi was U-35, then under Kapitänleutnant Waldemar Kophamel. The Senussi were not ungrateful for the aid supplied by the Central Powers. A senior Senussi gave two thoroughbred camels to the Kaiser, to be transported to the Austro-Hungarian naval base at Pola in U-35. The story was adapted by author John Biggins in his excellent novel, A Sailor of Austria. Later commanded by the War’s most successful submarine skipper, Kapitänleutnant Lothar von Arnauld de la Perière, U-35 sank 189 Allied merchant ships, and 2 warships, in the Mediterranean.

7. In 1917 the Ottoman General Staff established the “Africa Groups Command” (Afrika Grupları Komutanlığı), with the primary objective of diverting British efforts away from Mesopotamia and Palestine to the coastal regions of Libya. Yarbay (Lieutenant Colonel) Nuri Killigil, also known as Nuri Pasha, was appointed as commander. During the 1939-1945 War, he spent time in Germany organising the Turkestan Legion (Turkistanische Legion) to fight alongside the Wehrmacht in France and Yugolavia. He died in 1949, in a factory explosion that killed 26 other people.

8. Then a Major in the Cheshire Yeomanry, the Duke of Westminster (1879-1953) aided in the development of a Rolls-Royce armoured car, before commanding a unit of them in the W.F.F. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order for action in the Senussi campaign, including the daring rescue of imprisoned crews from wrecked ships at Bir Hakeim .

9. The I.C.C. were mounted infantry, formed in January 1916 in response to the Senussi Jihad; eventually there would be four battalions: the 1st and 3rd were Australians from the Light Horse, the 2nd was British, and the 4th was mixed Australian and New Zealand.

10. Lt. C.H.N. Ashlin was born in Rio Grande, Brazil, in 1892. After service in the Imperial Camel Corps he departed Egypt for the Western Front, where was wounded at Armentières. He transferred to the R.A.F. in June 1918, but returned to the Yeomanry after the Armistice. During the 1939-1945 War Wing Commander Ashlin was Chief Intelligence Officer for No. 6 (Royal Canadian Air Force) Group in R.A.F. Bomber Command. He died in 1974.

11. On 25 September 1916 T/Lt. G.D. Gardner was Mentioned in Despatches, followed by appointment as a Flight Commander on 30 April, by which time No. 17 Squadron was flying over the Macedonian Front. On 13 March 1918 Maj. Gardner succeeded Maj. Frederick Frank Minchin M.C. * (formerly Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry) as commander of No. 47 Squadron. However, he was invalided back to the U.K., and Maj. Frederick Alan Bates M.C. (formerly 1/1st Denbighshire Yeomanry) took over command, replacing Capt. Bernard Eddowes Berrington (formerly 9th Battalion, East Kent Regiment) who had acted in the position.

*On 27 August 1927, Lt.-Col. F.F. Minchin M.C., Capt. Leslie Hamilton and Princess Anne of Löwenstein-Wertheim-Freudenberg left Upavon aerodrome in a Fokker F.VIIA named St Raphael, hoping to be the first to fly across the Atlantic from East to West. After it was last seen some 17700 kilometres west of Ireland, the aeroplane disappeared, and no trace of the fliers was found.

12. Lt. H.D. Williams left No. 17 Squadron, now in Salonika, in August 1916 to train as a pilot in the U.K. On 24 February he was admitted to the New Zealand General Hospital at Brokenhurst, suffering from Rubella (German Measles). After recovery he was posted to No. 7 Squadron at Matigny, on the Western Front, to fly the B.E.2e, followed by the R.E.8. On 7 January 1918 he returned to the U.K. to serve as an instructor at No. 9 Training Depot Station at Shawbury. He was awarded the Military Cross on 17 January; the citation:

T/Capt. Henry Williams, Auckland Rifles and R.F.C.

For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty on 27 July whilst carrying out artillery observation. Although attacked by two machines, he carried on with his work, driving one off and destroying the other. He has consistently shown courage and perseverance in carrying out his work and set a fine example to the squadron.

He returned to New Zealand after the War, and was offered a position in the New Zealand Permanent Air Force, but opted return to farming. He died in 1981.

Article written by Gareth Morgan

Further Reading:

The VC that never was: Colonel Souter's gallantry against the Senussi, 1916