One of the last true cavalry charges: The Charge of The Dorset Yeomanry at Agagia, Western Desert, 26 February 1916

- Home

- World War I Articles

- One of the last true cavalry charges: The Charge of The Dorset Yeomanry at Agagia, Western Desert, 26 February 1916

Britain's declaration of war on Turkey on 5 November 1914 created a threat to the Suez Canal, a vital artery of the British Empire. Whilst the main threat to the Canal came from the east (across the Sinai desert) the Turks and their German allies recognised that a threat to the British from the west could assist their ambitions of cutting off the Suez Canal to allied shipping. To this end, negotiations took place between the Turks and the Senussi, a tribe which lived in the Sahara desert. The Grand Senussi Sayyid Ahmed ash-Sharif, leader of the tribe, agreed to attack the British. The Turks were to provide machine guns and artillery; the Germans were to deliver these supplies.

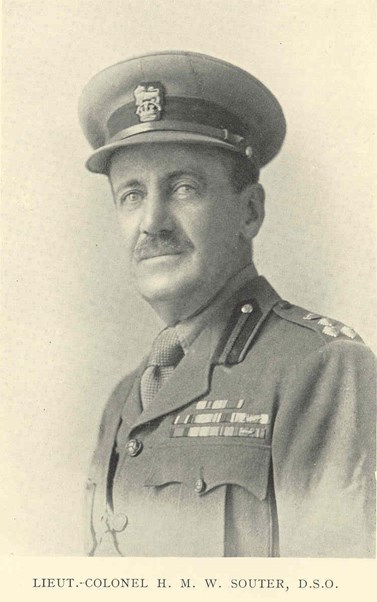

By the end of 1915, the campaign in Gallipoli was winding down and many units were withdrawn from the peninsula and transferred to Egypt. One of these units was the Queen's Own Dorset Yeomanry (QODY). Although still under strength despite a number of drafts, the QODY, commanded by Lt-Col Souter, a pre-war Indian Army officer, was ordered to join the Western Field Force (a unit tasked with quelling the Senussi) in January 1916.

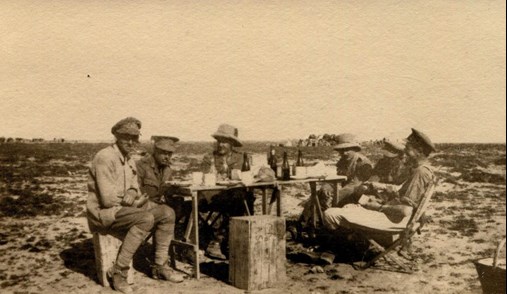

Photo: Lt Colonel Souter (centre) with a group of his officers

Led by Major-General Peyton the Western Field Force advanced along the coastal strip from their base at Mersa Matruh. The Senussi were brought to battle on 26 February 1916.

Photo: William Peyton serving as Delhi Herald of Arms Extraordinary at the Delhi Durbar in 1911

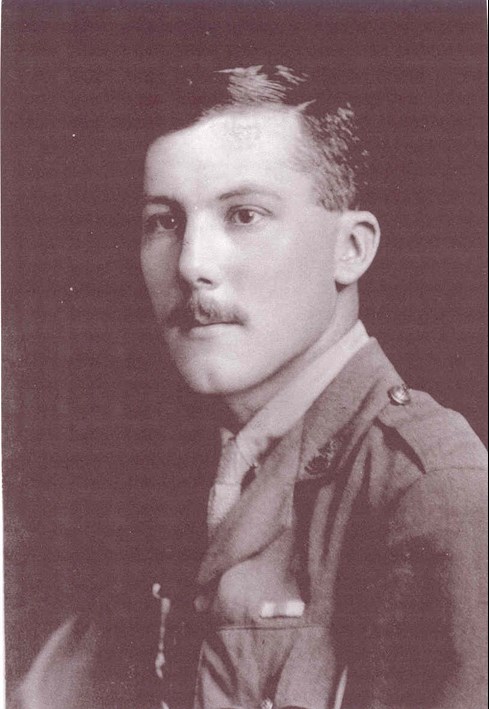

What follows is with the kind permission of the Keep Military Museum and the QODY Regimental Association, with particular thanks to WFA member Capt (ret'd) Colin Parr MBE, Curator/ Administrator, The Military Museum of Devon and Dorset. It is an extract from two letters sent by 2nd Lieutenant J H Blaksley dated 3 March and 29 March 1916 in which the Battle of Agagia is detailed.

Photo: 2nd Lieutenant JH Blaksley (Image courtesy of the Keep Military Museum and QODY Regimental Association)

What is remarkable about this action is that the cavalry charge by a supposedly modern unit of the British Army was made with drawn swords against a tribe of desert nomads who were armed with machine guns.

At last I am able to send you an account of our fight on February 26th, but I have to write it at odd moments and I am afraid it will not be the sort of account I should like to send, but I cannot help it.

On Sunday, February 20th, our column left Matruh and started trekking west. By Tuesday the column had reached Unjeala and the first fighting was on Thursday [24 February]. As we marched we had the sea on our right and the desert on the left; we were just following a line of telephone wires which ran along the line of wells. On Thursday Senussi snipers began firing on the troops, which were protecting our left. I myself was with the main body and had nothing to do with this; and the fighting was never on a serious scale.

On Thursday night we bivouacked at a place called Maktil, and here we knew from the aeroplanes that we were about 8 miles from the Senussi camp. The General in command [Peyton] decided to let the troops rest on Friday and then to make a night march and attack the Senussi at daybreak on Saturday. The country round Maktil is flat and perfectly open, but about a mile and a half to the SW there is a small hill. On Friday morning it was found that a few Senussi had got possession of this hill and were firing shots at our men and horses as they went out for water. They were soon silenced, however, and by ten o'clock all was quiet. Our side numbered about 1,600 infantry, three or four guns, and four armoured motor cars each carrying a machine-gun, and about 330 Yeomanry. The Yeomanry consisted of the Dorset's (about 210) and one squadron of the Bucks (120). We found out afterwards that the Senussi numbered 1,500 regular troops and about 1,000 irregulars. They had, however, four machine guns and some artillery. They were commanded by General Gaafar Pasha, who is a brother of Envar Pasha; General Nuri was in charge of the political and diplomatic side of the rebellion. Both were Turks of some distinction; Gaafar had been in command of the Dardanelles defences, an important post, as you will see. They also had a good many Turkish officers to help them. The regular army of the Senussi (the 1,500) were thoroughly trained men armed with the latest rifles; the 1,000, as I said irregulars and irregularly armed.

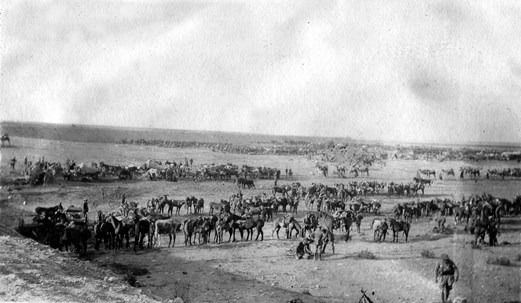

Photo: Regiment in rest, six miles from Sidi Barrani (Image courtesy of the Keep Military Museum and QODY Regimental Association)

“Desert Halt” Image courtesy of the Keep Military Museum and QODY Regimental Association.

Photo: QODY Regiment 25 Feb 1916 near to the coast at Sidi Barrani. (Image courtesy of the Keep Military Museum and the QODY Regimental Association)

Well, all was quiet on the Friday [25 February], we knew it would be dark by 6.30 and we had orders to be ready to start for our night march at 7.00. About a quarter to six the horses were feeding. Some were just coming back from drinking in a pond a few hundred yards away and we and all the men were just beginning our suppers before starting out when suddenly we heard firing and shells began dropping into the bivouac. Sufficient care had not been taken to watch the little hill to the SW, and the Senussi had got a couple of guns there. Our Artillery replied to them and in about half an hour they stopped and went away as it got dark. One shell dropped among the infantry and some more against the camels, and another just where I had been sleeping the night before; but fortunately most of them whistled over our heads and burst into the sea 100 yards behind us. Men who had been through the war from the start said that it had been a very trying half hour; we were taken by surprise, and felt so utterly helpless with the horses tied up with their nosebags on. Needless to say our meal came to a hasty end, and we began getting the saddles on as fast as we possibly could. The Senussi next attacked at long range, with some rifle fire, and the order for our night march was cancelled. Instead we had to form a ring around the camp (leaving a few men behind with the horses) in case of further attack. Nothing however happened, and about 11.30 we were sent back to rest until 4 a.m., when we had to be up and ready to move at dawn.

Photo: Brigadier General Henry Lukin

The Dorset Yeomanry were ordered to go straight for the little hill where the guns had been; we did so but found they had been taken away in the night. Then we pushed on three or four miles until we saw the main Senussi camp. It was now perhaps 6.30 (on Saturday morning) [26 February], and at this point the actual fight began. But, notice, we had rather a broken night and no food since Friday afternoon; we carried a few biscuits with us and a bottle of water each, and that was all. After we had located the enemy, firing began at long range. We were just waiting for the infantry, the guns and the General [almost certainly Brigadier General Henry Lukin] to come up. When the General turned up I was told off with the troop to act as his escort. I was not with him for more than half an hour, and then I rejoined my regiment; but during that half-hour I had a great opportunity of seeing from a small hill what was going on.

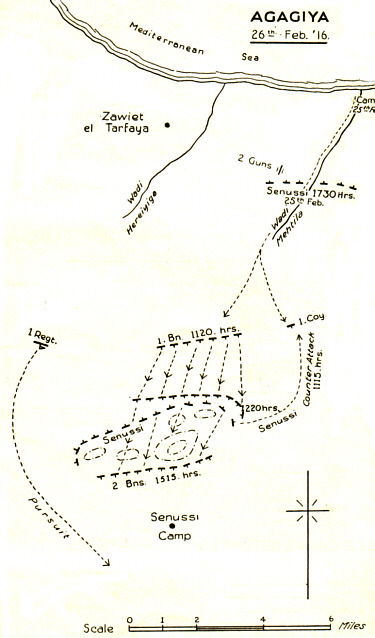

Map: the Battle of Agagia. The attack by the infantry on the morning of 26 February can be seen along with the beginning of the QODY’s flank move (Image courtesy of the Keep Military Museum and QODY Regimental Association)

You must imagine a slightly undulating plain of firm sand with low tufts of scrub 6 or 8 inches high. In front of us were some low sand hills of broken country, and this was where the Senussi had made their camp. Their policy was not to make a stand up fight, but like the Boers, to force us to attack them and lose a lot of men, while they slipped away into another position a few miles further back. This they had done with some success on Christmas Day and on January 22nd, and it was our Colonel's (Colonel Souter) great ambition to prevent their doing so again. Their worldly wealth consists chiefly of camels, tents, rice and dates. From the beginning we could see them (through our glasses) loading up their camels and slowly moving away. They had a great many camels – altogether it is estimated that they spread over a mile of ground by 300 to 400 yards wide; we saw all this while we were waiting. At last the infantry were ready, and off went the cavalry to the right. They were at once shelled and fired on by the machine guns, they lost very little. They had perhaps three miles to cross before they were again in safety, and it was magnificent sight to watch them galloping round, squadron by squadron all extended so as not to make to easy a target.

Half an hour later, the General [Lukin] dismissed me and I followed over the same ground with my twenty men, but the Senussi did not think it worth while to shell so small a force. When I rejoined the regiment they were fighting dismounted in the way I have described. The Senussi were moving away their camels, the infantry were attacking them from the front and we were harassing them from the side and behind.

The principle throughout the day was the same; we would fire at them from one position, then get on our horses and ride quickly to another and then fire at them again. I do not know much about the infantry, but the Senussi certainly kept their machine guns against us the greater part of the time, and I think they found us harassing. Their fire was often brisk, especially when we appeared in the open, and, as was inevitable, we began to lose men. So things went on until 3.30 p.m. By this time the Senussi must have been seven miles from the sand hills where they were in the morning and our infantry had not been able to keep pace with their retirement. We could hear nothing now of our own guns and three out of four of our armoured motor cars, which had done useful work in the morning, had by this time stuck in the sand. Further, our horses had had no food since 4a.m. and no water since the previous afternoon; and the strain was beginning to tell on the men. It was for the cavalry to strike a blow now or to let things drift as they had done in the fights on Christmas Day and January 22nd.

Photo: QODY Officers and men preparing for battle. (Image courtesy of the Keep Military Museum and QODY Regimental Association)

Before deciding to charge (as Colonel Souter told us afterwards) he had been waiting for two things, first to get them away from their old camping ground, where there might be trenches and wire pitfalls; secondly to get round their four machine guns. The first object was attained; we were well out in the open plain far away from the sand hills. The second object they were too skilful to let us attain. Each time as we moved on, trying to get round the machine guns they turned them equally as quickly and moved them to new positions, so that they always faced us. Clearly we had to charge into the guns or not at all. Then another point arose – I have mentioned that their line of camels was a mile long and 300 to 400 yards broad. They're fighting troops–their regulars-were all in their rear and flank to cover their retreat, their irregulars were with the camels. We were to charge the camels or to charge their fighting force? Of course the Colonel chose the latter and he led us so admirably that we were brought straight onto their General Headquarters.

During the day we had been firing at 900 or 1000 yards, at 3.30 p.m. our range was 1,200 [yards]. All the Dorset's were together except one troop. We probably numbered about 180. The Bucks squadron was not with us. Then the men were whistled up, we were ordered to "mount" and "form line". Then and not till then we knew what was coming, Imagine a perfectly flat plain of firm sand without a vestige of cover, and 1200 yards in front of us a slight ridge; behind this and facing us were the four machine guns and at least 500 men with rifles. You might well think it madness to send 180 Yeomen riding at this. The Senussi, too, are full of pluck and handy with their machine guns and rifles, but they are not what we would call first class shots; otherwise I do not see how we could have done it. We were spread out in two ranks, eight yards roughly between each man of the front rank and four yards in the second. This was how we galloped for well over half a mile straight into their fire.

Image: Lady Butler’s painting of the charge of the Dorset Yeomanry. (Painted in 1917). Commissioned by Colonel J Goodden, Honorary Colonel of the Dorset Yeomanry and Chairman of Dorset County Council, on behalf of 110 subscribers. (Image courtesy of Dorset County Council via the Keep Military Museum and QODY Regimental Association)

The amazing thing is that when we reached them not one man had gone down. At first they fired very fast and you saw the bullets knocking up the sand in front of you, as the machine guns pumped them out. But as we kept getting nearer, they began to lose their nerve and (I expect) forgot to lower their sights. Anyhow the bullets began going over us, and we saw them firing wildly and beginning to run; but some of them-I expect, the Turkish officers-kept the machine guns playing on us. We were within 30 yards of the line when down came my mare; she was, I think, the nicest I had ever ridden, a well known hunter in the Blackmore Vale, and in spite of want of food and water, she was bounding along, without the least sign of fear, as though she had just left the stable; down she fell, stone dead, fortunately, as I saw next morning, with a bullet straight through her heart. The line swept past me and I was almost alone, but the next moment I saw a spare horse; I snatched it and galloped after my troop; but within 100 yards down he fell like the mare. Then I had a very narrow escape; the second horse was not quite dead and was plunging; it took me a moment to get clear of him on the ground. I had barely done so when I saw a Senussi aiming his rifle at about 20 yards. I at once let fly with my revolver and over he rolled, but still on the ground he tried to get a shot at me, so I sent another shot after the first which settled him.

Photo: Lt Colonel Souter. (Image courtesy of the Keep Military Museum and QODY Regimental Association)

There was no other horse to get and I was alone, then a strange thing happened. Six or seven men had, I supposed, recognised me as an officer, anyhow they rushed up to me and abject terror began begging me for their lives. I saw they were men of consequence, but that was all I knew, the chief one was covered with blood, with a sword thrust through his arm. I stood over them as best I could with my revolver, and signed to them that if they stopped their men shooting at me, I would not shoot them. A few seconds later I remember seeing a Senussi shooting one of our wounded (they always do that). He was 50 yards off and I let fly with my revolver, but missed. Meanwhile the wounded officer had literally knelt down and tried to kiss my hand, begging for his life. Just then I saw Col Souter, who (like myself) had had his horse shot, and who had been momentarily stunned by the fall, and at the same time I heard cries of "Gaafar", and saw a few Senussi running towards me. I fired off a few shots-I do not know whether I hit or not-and Colonel Souter rushed up and put his revolver straight in Gaafer's face for the wounded officer was none other than he-and then began firing with me at the men who were coming on to rescue him. Gaafar was so terrified that he himself waved them back, and then with some difficulty Colonel Souter was able to get hold of a horse to put him on, and send him back off with the other officers, who were his staff, under an escort to the rear.

It would be difficult to describe what was going on in the meantime just behind us-such a scene of terror, as it is quite impossible to imagine. The Senussi were running in all directions, shrieking and yelling and throwing away their arms and belongings; the Yeomen after them, sticking them through the backs and slashing right and left with their swords. The whole thing was a marvellous instance of the awful terror inspired by galloping horses and steel. Some stood their ground, and by dodging the swords, and shooting at two or three yards range first our horses and then our men, accounted for most of our casualties; but it would be difficult to exaggerate their complete loss of morale as a fighting force. Had Gaafar or any one of his wretched staff-all Turkish officers, not Senussi-had an ounce of courage left, they could have shot Colonel Souter and me ten times over, put their wounded General onto one of the camels, which were not fifty yards away and taken him off. But they were half-mad with fear; the horse's hoofs had been too much for them. Nuri was ridden down; whether killed or wounded or only knocked over we do not know, but they got him away on a camel.

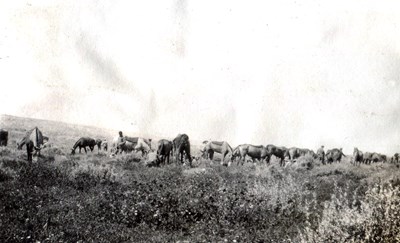

Photo: QODY Horses relax for a while after the battle. (Image courtesy of the Keep Military Museum and QODY Regimental Association)

This was the end of the day; the infantry were far behind; the guns had gone home. If only we had had a second regiment to charge behind us, we would probably have captured the machine guns and Nuri as well. But the Dorset's alone were too weak in numbers, and too many officers had fallen, for a mounted second charge, and the horses were completely played out. It is estimated that from 300 to 500 Senussi were killed or wounded in it, and perhaps a still more important factor was their loss of morale. At all events, for the next two or three days we saw parties deserting and going back to their homes, carrying white flags, many of them with their heads and arms tied up. Our total losses in the regiment for the day were 4 officers and 28 men killed, and 2 officers and 28 men wounded.

Photo: QODY Dabaa Railhead and Supply Point. (Image courtesy of the Keep Military Museum and QODY Regimental Association)

The wounded are doing well, and neither of the wounded officers is badly hit. In the charge, the squadron I belong to "B" Squadron was on the right, and my troop was on the extreme right of the whole line; it happened that we came in for it more heavily than the left. Of the four officers in the squadron two were killed and one was wounded, and I was the fourth. I led 17 men (being my troop) into the charge, of whom 11 were killed and 1 got back wounded; only 5 were untouched. I had a bullet through the case of my field glasses, and another through the pocket of my tunic; so my tunic is now quite a relic, with the bullet hole on one side and old Graft's blood on the other! Altogether, you will see I have a lot to be thankful for in getting through untouched.

Colonel Souter has fought in India and during the war in France and Gallipoli, and he said he had never been in such a tight corner before. It would be difficult to speak too highly of his leadership throughout the day; he did the whole thing himself, and at one time in the charge he rode 300 yards in front of our lines to see exactly whether we were going straight.

The next day he saw Gaafar-instead of being broken and in fear of his life, he was then polite but rather contemptuous; of the charge he said; "C'est magnifique, mais ce n'est pas selon led regles, then he added; "No one but British Cavalry would have done it." Some two hours of daylight remained, and this went in trying to get back to our wounded. It was a hard task, and I fear we did not get them all. Later we found a pond, where we watered our horses and a good well, where we got water for ourselves. We bivouacked for the night beside this well, and fortunately were able to get some dates from the Bucks squadron, as they had captured a lot of camels loaded with them. But we had little rest that night; a third of the men stayed with the horses, and the rest of us had to form a ring round the bivouac in case of a sudden attack. It was a weary night and a very cold one; but there was no attack, and at last the morning came.

It was Sunday, and after having a little food, we saddled up and went out to look for our dead. It was a sad business. We found them all, but they were all stripped of every stitch of clothing, and in a few cases horribly battered and mutilated. They were brought back on carts and buried, a chaplain being there to read the funeral service. Then at 3 o'clock we started again. We had to go back to Maktil for water and food, and it was 9 o'clock at night before we got it; but we had done our work, and the ground was clear for other troops to go on.

The infantry, with one of our squadrons, occupied Sidi Barrani the next day, and the rest of us will join them there shortly. It was simply uncertainty about water that made the General send us back; at some time we were within five miles of Sidi Barrani, a coast guard station, which we had been forced to abandon in the autumn.

The frontier post at Sollum is 55 miles further west, and that was our next and final objective; so on Saturday, March 11th, we started trekking again towards Sollum. We numbered altogether 5,000, with Peyton personally in command. There is a ring of rocky hills, about 1,500 feet high, round Sollum and we expected the Senussi would make another fight in the passes, where they could have taken up a very strong position; but they thought better of it and retreated, and by the Monday night (March 18th) we heard our infantry held these passes and so commanded the way into Sollum. We had a long march on the Tuesday all round the hills, looking for stragglers and refugees, and in our march we went right to the Tripoli frontier. We did not find many, and got back late at night into Sollum with very few shots being fired. But very fine work indeed was done by the Duke of Westminster and his armoured motor cars. Our aeroplanes found the Senussi retreating 20 or 30 miles away to the south, and the armoured cars at once gave chase, and they charged right into them and captured one of their guns and two or three of their machine guns and some Turkish officers.

Two days later they again distinguished themselves in having rescued the unfortunate British mariners who had been in the hands of the Senussi since last November. Everyone here thinks very highly indeed of the Duke and his plucky work.

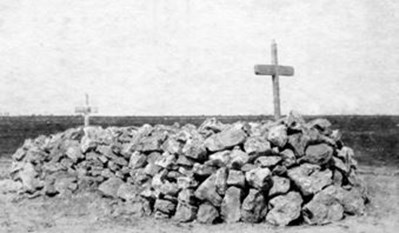

Well, this ended the business; our charge on February 26th had hit them sufficiently hard for them not to want to stand again, and now the cars had gone into them as they run away. The reason was that they stuck in the sand on the 26th, or it all might have been finished by then. We only stayed two days at Sollum. The Union Jack was hoisted over the fort and saluted by guns, then through the ever present water difficulty we started trekking home at once. On our march we re-visited the battle-field and put up a cairn of stones and a wooden cross over the grave; this was then photographed and a photo will be sent to each of the families. We then trekked back to Matruh without anything of interest occurring. It is most satisfactory to have given them a thorough beating, to impress the native population all over Egypt. The Senussi are a Mahomedan sect, not a tribe, and if they had had success, very likely they would have been joined by thousands of waverers and secret friends; as it is they will all see now that it does not pay to take up arms against us; in Egypt they have lost many lives and had all their villages and crops burnt; I think it has given them a lesson.

J H Blaksley

2nd Lieut Dorset Yeomanry

Photo: The large grave of those who fell at Agagia 26 Feb 1916. there is also a smaller grave containing 15 bodies by the side of the cairn. (Image courtesy of the Keep Military Museum and QODY Regimental Association)

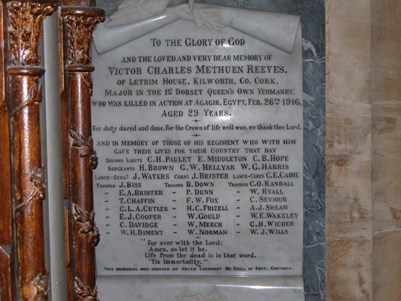

The most senior casualty of the charge was Squadron Commander Major Victor Reeves who is remembered on a memorial plaque at St Peter's Church, Chetnole, in Dorset.

Photo: Major Reeves. (Image courtesy of the Keep Military Museum and QODY Regimental Association)

Photo: Memorial to Major Reeves at Chetnole, Dorset. (Image courtesy of the Keep Military Museum and QODY Regimental Association)

Contributed by David Tattersfield.

Further Reading:

The VC that never was: Colonel Souter’s gallantry against the Senussi, 1916