Horatio Bottomley: media mogul, public orator and fraudster

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Horatio Bottomley: media mogul, public orator and fraudster

Horatio Bottomley was, for around 15 years either side of the First World War, one of the best-known and most popular figures in British public life. A Member of Parliament he was also a media mogul, public orator but also a swindler and fraudster. His eventual fall was – with hindsight – as inevitable as it was deserved. His story, which is summarised below has a degree of similarity with that of Robert Maxwell. In Bottomley's case, however, the multiple-bankrupt, corrupt businessman and serial litigator was 'found out' in his lifetime.

Above: Horatio Bottomley addressing a recruitment rally in Trafalgar Square on 9 September 1915

Bottomley's early life was quasi-Dickensian in its tragedies. Born in 1860, he lost both parents before he was five years old, but after being looked after by his extended family, was eventually placed into Sir Josiah Mason's Orphanage in Birmingham at the age of 9, from where he ran away aged 14.

Above: Sir Josiah Mason's Orphanage

Early jobs and business dealings and the Australian Gold Mining company scam

After several basic jobs, including a failed apprenticeship as a wood engraver, he found work at a firm of legal shorthand writers in London. He later became a court reporter - which may explain how he was later able to 'get himself off the hook' in numerous cases that were brought against him. He seems to have been very successful in this career, as the firm he worked for took him on as a partner, changing the firm name to 'Walpole and Bottomley'. This improved his impoverished financial position and he and his new wife (Eliza) were able to move into somewhat better accommodation than hitherto. Horatio and Eliza had one child, a daughter named Florence.

When he was aged just 22 Bottomley launched a newspaper: the Hackney Hansard, he later launched the Battersea Hansard but this was losing money, so he merged the two newspaper. Over the next two years his activities in this field increased (which brings to mind the career of Robert Maxwell one hundred years later) acquiring a small chain of newspaper, but shutting down those that lost money. By means of his powers of persuasion and salesmanship, he succeeded in increasing the circulation of some of these titles, which would have encouraged him into further expansion of his business activities. Approaching a city financier he persuaded him to help with the raising of capital to purchase another firm of newspaper publishers and printers. It is possibly at this point his use of 'smoke and mirrors' started in earnest - paying large dividends to the shareholders to give the appearance of a highly successful business. In 1888, with others, he founded the Financial Times and briefly employed Alfred Harmsworth (the future Lord Northcliffe and later owner of the Daily Mail) as a sub-editor. But within a short period of time Bottomley had over extended himself.

In 1889 he floated the Hansard Publishing Union but in a series of very dubious transactions 'milked' the company, with over £100,000 (nearly £11 million today) ending up 'missing'. The company went bust and Bottomley was charged with conspiracy to defraud. At the subsequent trial it was fully expected he would be found guilty and given a long prison sentence, However Bottomley conducted his own defence and managed to get the judge 'on side'. The members of the public who turned up did so with the expectation of being thoroughly entertained by the proceedings. They were not disappointed. At the end of his closing speech, applause broke out in the court. (One of those taking part sniffily remarked that Bottomley's long speech 'showed an ignorance of grammar and a cockney incapacity to pronounce the letter h.') The jury took only a few minutes to acquit him.

Above: Horatio Bottomley c.1890 aged 30

Bottomley now founded the Joint Stock Trust and Institute as a method for floating a number of Western Australian gold mining companies. These concerns, if they existed at all, were little more than ‘holes in the ground’. At this time he floated some 50 companies set up to sell these mining concerns. The vast majority either failed, going into liquidation, or were reconstructed under a new name. Occasionally one of the companies was successful. For instance the Great Boulder Mines Company shares, which he bought for two shillings, eventually rose to £13 each.

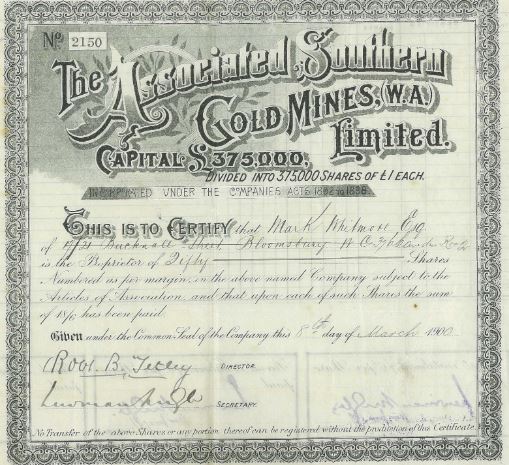

Above: One of Bottomley's Gold Mining Company Share certificates. His signature appears at the bottom

The Gold Mining company scam was used to raise money to pay off those who lost money with his bankruptcy as a result of the Hansard Publishing Union insolvency, but little cash ended up being remitted - most of those who were owed money were persuaded to accept shares in the West Australian Loan and General Finance Company - a concern linked to the Gold Mining Company scheme!

The Joint Stock Trust and Finance Corporation was not a mining company but operated (or pretended to operate) as a company that held shares in other companies. It had been 'reconstructed' from an earlier 'Bottomley' company (The Associated Finance Corporation) that had that gone into liquidation. His routine was to invite those who owned shared in the liquidated company to apply for shares in the new 'reconstructed' company at a massive discount.

According to the information Bottomley put out the Joint Stock Trust would make money for its shareholders through the operations of its subsidiaries. It was, of course, a scam. Bottomley gambled the money that came in from the gullible subscribers of the shares. The fraud was uncovered by a solicitor named Edward Bell who Bottomley tried to bribe into silence. Bell was not to be bought off and took it upon himself to bring Bottomley down.

One of Bottomley's victims of the Joint Stock Trust Scam (a Mr Platt) turned up at Bottomley's flat threatening to shoot him if he did not refund the money he had lost. Bottomley turned on his full charm, entertained him with champagne, and not only avoided repaying the victim, but also persuaded Platt to hand over a cheque for £4,000 (£407,000 today). Platt was one of the lucky ones as he brought an action against Bottomley in 1909 and managed to recover his losses.

Another of the many examples of Bottomley's reprehensible behaviour also gives an indication of the staggering sums of money involved. Robert Masters was an incredibly wealthy retired official of the Indian Civil Service. He was persuaded to part with £90,000 which bought him 'dud' shares in a number of Bottomley's companies. Realising he had lost a large proportion of his fortune he left London and kept this secret. Having a failing memory, when Bottomley sent a circular to his earlier victims offering to make good their losses, Masters was taken in, met with Bottomley and handed over another £42,000. Although Masters died a pauper his daughter took Bottomley to court in the summer of 1911 and won the case. Bottomley was not perturbed, he was by now on the brink of bankruptcy for the second time and said that Masters' daughter would not see a penny in view of his impending Bankruptcy.

Above: Associated Southern Gold Mines, (W.A.) Ltd was one of the many Bottomley companies which he used to fleece unsuspecting investors. It had an authorised capital of £375,000

Things came to a head when Bottomley tried to reconstruct the Joint Stock Trust and Finance Corporation and it was noticed that the number of votes cast by shareholders was disproportionate to what would have been expected. The case came to court and it was revealed that of the two million shared that were authorised (giving the company total capital of £500,000) these had been re-issued to different individuals up to six times. In effect there were multiple owners (and therefore subscribers) for each of the company's legitimate shares. This should have been enough to convict Bottomley of fraud but, once again conducting his own defence, by destroying the credibility of a key witness and by the stroke of luck of having the examining magistrate taken ill and having to be replaced (which he turned to his advantage) he was able to 'get away' with the fraud charge and avoid being convicted. When the verdict came down from the bench, there were loud cheers in court (probably mainly from hired supporters he placed in court - and elsewhere - to generate 'heat and noise' in his favour).

In Parliament

Bottomley stood as the Hackney South Liberal candidate in the 1900 General Election. (This was his second attempt – he had previously stood in 1887). He lost again but, it was a close run vote. During the election campaign he was attacked in writing in a newspaper article, in which he was accused of being a fraudulent company promoter, and a share pusher. Bottomley sued for libel, conducing his own prosecution. The jury came down in favour of Bottomley and he was awarded £1,000 damages. Although no doubt the money was gratefully received, it had the effect of dissuading others from locking horns with Bottomley in court. This is again shades of Robert Maxwell 100 years later.

Standing for parliament the third time, was swept to victory in 1906. He wasn’t welcomed in the House of Commons. His reputation as a crooked businessman was well known and whenever he rose to speak, Liberal MPs talked loudly among themselves, in an attempt to put him off.

Bottomley suggested a number of policies, such as to abolish beer duty, and replace it with a tax on fizzy drinks. He even made a call for peerages to be sold on the open market to fund welfare spending. It is ironic that Lloyd George subsequently partly followed this suggestion!

Nevertheless some of Bottomley's activities were serious and for the public good. He spoke eloquently in favour of Old Age Pensions, suggesting the Government could raise money via an Employer's tax on wages, super-tax on investments, Stamp Duty on share transactions, a tax on Racing and Betting stakes (something which he obviously knew a lot about!) and the state appropriating dormant bank balances. Many of these policies are important ways for Governments to raise taxes and gather income to this day.

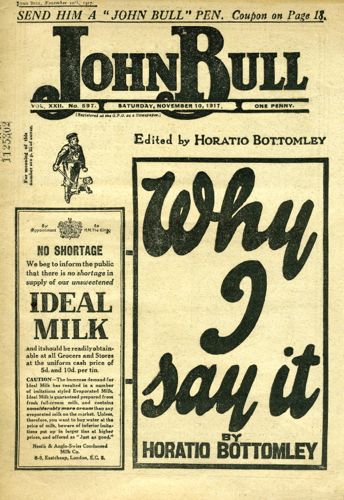

1906 was also the year he founded John Bull (another periodical of this name had been published for many years during the 19th Century). This second incarnation of the magazine was relaunched in a tabloid style that proved incredibly popular. Among its regular features Bottomley wrote "The World, the Flesh and the Devil" column and also adapted the slogan: "If you read it in John Bull, it is so".

Above: "The World, the Flesh and the Devil" was a regular column, written by Bottomley. This edition is from 1921. At this stage he was sitting as an independent MP hence the 'Politics without a party' statement on the masthead.

Despite the immediate success of John Bull, which became even greater over coming years (by 1912 the circulation was to hit 1½ million) Bottomley still was spending more than he was raking in. He was served with forty Bankruptcy Petitions in 1906 alone, however he refused to cut down on his expensive lifestyle.

John Bull's campaigns and prizes and Bottomley's 1912 Bankruptcy

Within a month of the first edition, John Bull published a prospectus for the John Bull Investment Trust. The Managing Director being (obviously) Horatio Bottomley. Subscriptions of at least £10 were required and the promise made that exclusive information on companies would be provided. This was lucrative, and important to Bottomley given the bonanza of the Australian Mining Company shares had run its course.

A frequent feature of John Bull was the sweepstake. It is likely many of these were outright frauds. These had to be organised from Switzerland to 'get around' the UK laws on these competitions, and the first of these offered a first prize of £15,000 on the winner of the 1913 Derby. Confusion reigned when the race took place as this was the event that was affected by the death of a suffragette running in front of the King's horse. Bottomley's total takings were around £270,000 which made this very profitable, even if the first sweep was not 'fixed'.

In a subsequent sweepstake he announced that the first prize of £25,000 (£2.5 million in today’s money) was a blind widow of Toulouse named Madame Glukad, who was in reality the sister of one of his associates. After a great deal of early publicity, she disappeared - apparently to escape all the offers of marriage she had received. It would seem that she had been paid £250 with Bottomley keeping the rest.

One of the main thrusts of Bottomley's John Bull magazine was the cause of consumer protection. To facilitate this, he created the 'John Bull Exposure Bureau' and employed retired police officers and private investigators to responded to issues submitted by readers.

The publication of the cases investigated by the bureau opened the floodgates for libel writs to be served, which escalated to four writs being received every week. Bottomley was not perturbed, stating he'd argue each of these himself. Eventually, however, the future Solicitor-General and Attorney-General, FE Smith MP (later the Earl of Birkenhead) was employed to challenge such writs. The number of libel cases eventually diminished.

Of the cases taken up by the Exposure Bureau possibly the most high profile was its allegations regarding the activities of the Prudential Assurance Company, Britain’s largest insurance company.

Above: A cartoon in John Bull (9 March 1912)

The anti-Prudential campaign was launched in March 1911. Numerous charges were made against the insurance company, including mis-selling by Pru Agents who persuaded existing policy holders to take out unnecessary additional policies. These accusations were disputed by the Prudential and the publicity generated by the campaign raised the profile of John Bull but, as with many investigations undertaken by the Exposure Bureau, it ended only with legal proceedings for libel. Bottomley was forced to discontinue his action due to the evidence put forward by the Prudential and this left Bottomley personally liable for a significant amount of legal costs.

Bottomley’s growing debts reached a crisis in 1912. Although he had been cleared of fraud with the Joint Stock Trust and Finance Corporation case, it did not mean he was off the hook for the individuals who had lost money. On 1 February 1912, it was ruled in court that he was liable to the shareholders of the Joint Stock Trust - the sum totalled over £36,000 but with interest added came to nearly £50,000 (£4.8 million today). His total liabilities amounted to a staggering £233,000 (£22 million today). This judgement forced him into bankruptcy for the second time and he had to give up his seat in parliament via a process known as the 'Chiltern Hundreds'.

High Life: Horses and Mistresses

Horatio lived for a number of years in a luxurious apartment at 56a Pall Mall (although he had to give this up following his 1912 Bankruptcy) and enjoyed a lavish life-style which included a taste for wine: he breakfasted on champagne and kippers!

Above: 56a Pall Mall - Bottomley's luxurious apartment (the location is in front of the Belisha Beacon on the Zebra Crossing)

His high level of expenditure was further exemplified by him owning a number of racehorses. He had no knowledge of how to spot a good prospect, so most of those he bought ended up as 'duds'. However, he did have success; he twice won the Cesarewitch including the 1904 race with – incredibly in terms of the impending hostilities – a horse named ‘Wargrave’. His racing colours were red, white and black, the same as those of Wilhelm II, but he refused to change them, apparently saying "for the German Emperor, like my horses, will never win."

Above: Wargrave, winner of the Cesarewitch in 1904

Bottomley’s horses never won the Derby or the Grand National, even though he spent a substantial amount of money trying. He was a god-send to bookies and lost a great deal of money on betting on his own horses. (An exception was his second win in the Cesarewitch race in 1912: this netted him £70,000 on the day, but it was largely used to off-set his betting losses.) Unlike his other business dealings, he invariably settled his betting accounts.

Shortly before the first world war, Bottomley devised what he believed to be certain method of winning a fortune. Before a race in Blankenberge, Belgium he bought all of the six competing horses. He paid six jockeys and instructed them to finish the race in a specific order. Everything seemed to be going well until a heavy fog came in from the sea, reducing visibility on the entire course. As a result, the jockeys couldn't see each other, so finished in the ‘wrong’ order. Bottomley lost a fortune.

Despite the outcome of this attempt to defraud bookmakers, Bottomley had amassed a great deal of money, which enabled him to purchase Dicker House at Upper Dicker, near Eastbourne. Berwick, the local train station, was built where it was because Bottomley influenced the decision in parliament; the stop was originally called 'The Dicker Halt' after the estate. The property is now Bede's, an independent day and boarding school. In order to avoid losing the property, he transferred ownership of this to his son in law (Florence, his daughter had married a race-horse owner called Jefferson Cohn) prior to his 1912 Bankruptcy.

Horatio Bottomley enjoyed numerous mistresses. These were usually petite, auburn-haired chorus girls, barmaids and waitresses. He often carried on three affairs simultaneously, but kept the fact secret from each of them. It seems his wife accepted his infidelity. The girls were set up in rented flats and showered with flowers and gifts.

Bottomley was having lunch one day with his secretary, Henry Houston, at Romano's (a very upmarket restaurant on the Strand) when he spotted a very pretty young girl who was with an older man. He was so immediately smitten, that he put his lunch to one side and hurried after her. Peggy Primrose was her name, she was 20 years old, unhappily married to a 'gentleman of leisure' (Aubrey Lowe) and was - although herself from a wealthy family - appearing as a chorus girl in a musical comedy the Dollar Princess. She became his long term mistress and 'love of his life'.[1]

Above: May Esther Lowe (nee Fitzmaurice) a.k.a. Peggy Primrose (1890-1956) pictured in 1913, who was Bottomley's long term mistress (Ancestry: Dollman family tree)

Above: A short piece about Peggy in the Daily Mirror 4 March 1916

Aubrey Lowe, Peggy's husband was not prepared to let matters go without (literally) a fight. It was on the evening of Bottomley losing the Masters case (see above) that Lowe accosted Bottomley on the Strand, with a cab driver accompanying him as a witness (he was expecting to be prosecuted for what he had in mind and a witness would be useful). "I've got you at last" were apparently the words with which Lowe greeted Bottomley, and proceeded to knock him into the road. The event was reported in the press, as can be seen below.

Above: Although deliberately not stated in this article (in the Kalgoorlie Miner, WA of 28 February 1912), Bottomley's 'thrashing' in the Strand was at the hands of Peggy's cuckolded husband.

Bottomley was cited as a co-defendant in Peggy's divorce proceedings. The divorce petition (dated 2 October 1913 which is available online) lists him having committed adultery at his mansion 'Dicker', his apartment at 56a Pall Mall, The Royal Hotel Princess Street Edinburgh, The Bush Hotel Farnham, at Douglas on the Isle of Man, The West End Hotel on Piccadilly, at Bedford Court Mansions in Bloomsbury (which was the location of the flat where he 'installed' Peggy), at Ostend in Belgium and 'on diverse other dates unknown'.

Above: Bedford Court Mansions, Bloomsbury

Clearly Mr Aubrey Lowe had the wealth and determination to end his marriage by employing detectives. Interestingly, Aubrey's earlier two marriages seem also to have ended in divorce.

Wartime editions of John Bull

After the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28 June 1914 in Sarajevo, John Bull described Serbia as "a hotbed of cold-blooded conspiracy and subterfuge", and called for it to be wiped from the map of Europe. However, when Britain declared war in August, the magazine quickly changed position, and was soon calling for the elimination of Germany.

John Bull campaigned relentlessly against the "Germ-huns", and against British citizens carrying Germanic surnames. The magazine throughout the war called out what it perceived as the danger of "the enemy within".

Above: John Bull, 22 August 1914

John Bull magazine claimed a circulation in excess of 2 million by 1914, making it (if the numbers can be believed) the best-selling news weekly of its day. Clearly the circulation numbers for John Bull was significant and provided Bottomley with a platform through which he was able to promote both his financial and political interests.

Appeals were made in John Bull for readers to send five shilling to pay for 'Jack and Tommy comfort parcels'. The response was excellent and various companies were persuaded to take part, with Bovril, Lyons, Liptons and Black Cat cigarettes being contributed. John Bull simply paid for the postage. There is no evidence that this was one of Bottomley's frauds. Perhaps this scheme was perfectly legitimate and genuinely helped those at the front.

The rhetoric became increasingly outrageous.

“If by chance you should discover one day in a restaurant that you are being served by a German waiter, you will throw the soup in his foul face, if you find yourself sitting at the side of a German clerk, you will split the inkpot over his vile head.”

Then, after the Lusitania was sunk ‘“You cannot naturalise an unnatural beast – a human abortion – a hellish freak. But you can exterminate it.”

A recurring theme throughout the series of war-time John Bull magazines is that the soldiers are able to win the War, but are constantly undermined by the incompetent government. Haig is ironically commended for finally getting round to ordering body shields for the troops, which John Bull suggested ‘months ago’. Bottomley was happy to supply the 'solutions', but also asked awkward questions:

'Why is not every British ship provided with a 3-inch gun and a gunner? Surely this would be the most effective way of stopping the submarine menace.'

'Why is it that potato farmers are allowed to use soldiers for lifting their crops, only to sell at grossly inflated prices?'

'Why are soldiers rotting at home through over-training, while thousands of care-worn and war-worn men can get no leave at all?'

Above: John Bull, 10 November 1917

Typically in the edition of 19 August 1915 John Bull states:

‘Our Pledge: No Case of hardship or injustice, no instance of beggarly cheeseparing, shall go unchallenged or un-remedied.

Grievances are made into news stories:

'On some golf links in Sussex a raw recruit encountered a person dressed in civilian trousers and a military tunic. The boy did not know he was an officer, and failed to salute… The unfortunate boy is now enjoying 14 days in the cells.'

Not only did Horatio Bottomley write for his own John Bull periodical but he was also approached by the Harmsworth brothers, Alfred (later 1st Viscount Northcliffe and who is mentioned above, and whom Bottomley had previously employed) and Harold (who later became 1st Viscount Rothermere): the brothers owned numerous newspapers including the Daily Mail, Daily Express and The Times. They wanted Bottomley to write for an illustrated Sunday newspaper they were about to launch - the Sunday Pictorial. Although they were on bad terms with Bottomley, they recognised his jingoistic utterances would 'sell'. They reached an agreement that was lucrative to Bottomley, and the first edition came out in March 1915.

Above: Sunday Pictorial front page from May 1916 - Bottomley's name can be seen prominently at the top of the page. (Mary Evans Picture Library)

Within a few weeks of the launch, the Lusitania was sunk, and he was able to give full vent to his rhetoric.

'And now comes the news of the Lusitania massacre. I want every German now in Britain to get away sharp - never mind how long he has been 'naturalized'. You cannot naturalize an unnatural freak - a human freak. But you can exterminate it.

For these articles he was paid £150 per issue which - over the course of 52 weeks - was the equivalent today of over £130,000 per year. Being exceptionally busy, however Bottomley soon 'outsourced' the writing of these to staff on his John Bull magazine. He would approve the text and 'top and tail' the copy. Although he paid the ghost writers, this remained lucrative for him, and is a further example of how the public would lap up anything purporting to be from Horatio Bottomley.

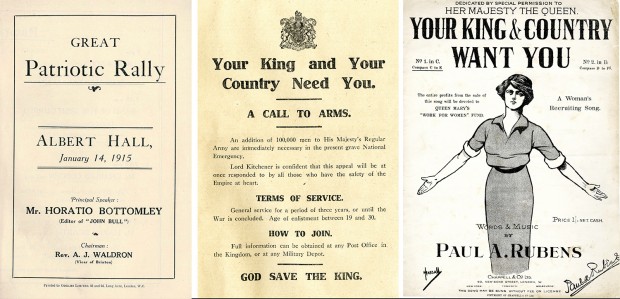

Recruiting Sergeant

Bottomley became one of Britain’s most successful recruiters for the war effort. His first recruiting rally was at the Royal Opera House in September 1914. Another rally took place at the Royal Albert Hall on 14 January 1915 and it was reported that thousands of people had to wait for hours on the off-chance of gaining entry. The schedule included patriotic songs, recitals of poems (including those he composed) with representatives from the army and new recruits on stage. These were such massive successes that he repeated similar rallies up and down the county.

Above: From the Great Patriotic Rally of September 1914 programme

After the success of these early events, Bottomley wrote to Prime Minister H.H. Asquith to sound out the concept of him becoming Director of Recruiting. Asquith politely responded: "Thank you for your offer but I shall not avail myself of it at the moment. You are doing better work where you are."

Bottomley spoke at various recruiting meetings during the course of the war and gave over three hundred "patriotic war lectures". He stated that he was not going to take money for sending men out to their death, or profit from his country in its hour of need. It seems this is not true, as he often charged an appearance fee of £200 (more than £17,000 today). He also took a cut of the door money.

These events tended to be in music halls. He became the most popular speaker in the country.

Previously he had been critical of the government, but at these gatherings he invariably announced:

"When the country is at war, it is the duty of every patriot to say: My country right or wrong; My government good or bad."

These rallies were initially to encourage recruitment, but also were to raise funds for war charities and - later in the war - to sell government bonds. This selling of Government bonds was to become a lucrative fraud in due course, and bring about his final downfall.

Above: Horatio Bottomley addressing a recruitment rally in Trafalgar Square, 9 September 1915

Above: The Trafalgar Square rally was reported in the Daily Mirror the following day, 10 September 1915

Above: Another instance of Bottomley recruiting. Date unknown.

At one meeting a man in the audience shouted out: "Isn't it time you went and did your bit, Mr. Bottomley?" Bottomley replied: "Would to God it were my privilege to shoulder a rifle and take my place beside the brave boys in the trenches. But you have only to look at me to see that I am suffering from two complaints. My medical man calls them anno domini and embonpoint. The first means that I was born too soon and the second that my chest measurement has got into the wrong place."

In 1916 Bottomley helped Noel Pemberton Billing to be elected as the independent MP at a by-election. Both men used their publications to claim the existence of a secret society called the Unseen Hand. Bottomley even stated this group was responsible for the death of Lord Kitchener.

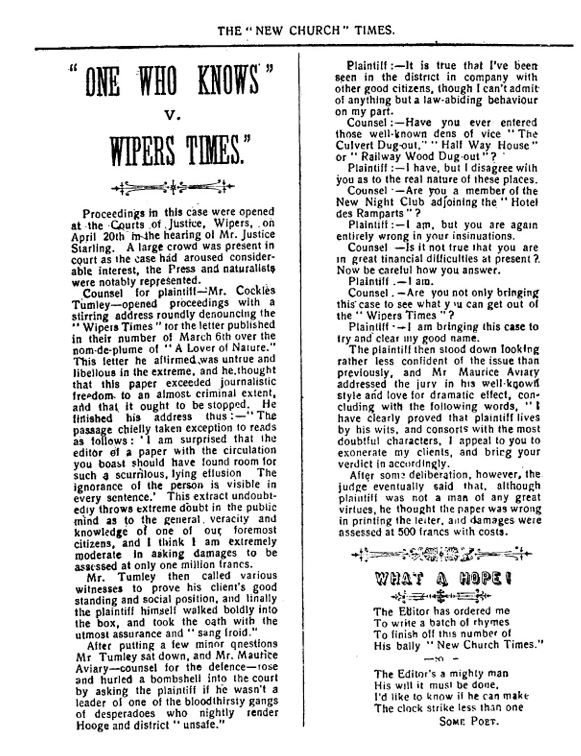

It is unclear what the soldiers at the front made of Bottomley and John Bull. There is evidence that at least those who published the Wipers Times did not think much to him. Many of the famous were mocked in this publication and given pseudonyms. For instance ‘Teech Bomas’ (William Beach Thomas of the Daily Mail) and ‘Belary Helloc’ (Hilaire Beloc). So it was that Bottomley became 'Cockles Tumley' (Cocles was the surname of Horatius who saved Rome by defending a bridge - it is possible that only those with a classical education would have 'got' the joke here).

Above: The 'New Church' Times, 1 May 1916

Although deeply suspicious of Bottomley, he was utilised by the Government when it was thought he could be of use: in April 1915 Lloyd George (who was at that point Chancellor of the Exchequer) asked Bottomley to address to workers in Glasgow who were threatening industrial action. Bottomley's intervention averted the threatened strike. He later was sent on unofficial visits to give talks to munitions workers, coal miners and railwaymen. These visits did not enable him to join the Government as a Cabinet Minister, which is something he really wanted to achieve.

It was not all plane sailing for Bottomley, though. Two business men who had lost money in their dealings with Bottomley joined forces and started issuing highly critical pamphlets in towns where he was due to give a lecture. Bottomley eventually gave in to this pressure, and refunded one of the businessmen the £4,200 he was owed. The other businessman was Reuban Bigland, who Bottomley had treated badly previously. Bigland was only owed £50, and Bottomley also paid him off. Although peace was restored with Bigland, this was not to last.

Above: Although the context is unknown, the above image (courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery) shows Bottomley in September 1918 in the wig and gown of a barrister.

Visit to the front line

Bottomley - presumably to reinforce the idea of his being a friend to the soldier - thought that a visit to France would increase his profile and wheels were put in motion for a visit in September 1917. As ever, money was on Bottomley's mind and he secured £1,000 in expenses from the Sunday Pictorial (for whom he was to write) plus further expenses from his own John Bull magazine.

It appears that Bottomley was unimpressed with the lack of luxury he found. Asked if he would like a drink in an officers' mess and offered various options, he replied 'I never drink anything but the driest champagne' of which - unsurprisingly - there was none available.

This must have been seen as an 'official' visit as there are a total of twenty photographs captured by Lt Ernest Brooks (the official photographer). These images can be seen online in the Imperial War Musuem's collection show Bottomley's car being held up to show his pass at Arras (Q2796, Q2797, Q2798); Bottomley inside the ruined cathedral at Arras (Q2799); Bottomley watching shrapnel bursting round an aeroplane near Arras (Q2800); Bottomley about to leave a Divisional Headquarters for the front line at Arras (Q2801); and the general showing Horatio Bottomley the German front line, and the shells falling on it near Oppy (Q2802) (see image below).[2]

The tall civilian shown in many of these images, although unnamed, is actually Henry Houston who was Bottomley's secretary for many years.

Other photos at the IWM show Bottomley in a trench watching shrapnel bursting round a British aeroplane at Fampoux (Q2803); Bottomley in a trench watching an aeroplane fight near Oppy Wood (Q2804); Bottomley in a trench with a Divisional general; near Oppy Wood (Q2805); Bottomley talking to two soldiers at Athies (Q2806); Bottomley accept[ing] a potato from a soldier's mess tin, as he passes through a trench near Oppy Wood (Q2807); Bottomley and his secretary wearing gas-masks in a trench near Athies (Q2808 and Q2809) (see image below).

In view of his experiences at 'music hall' type gatherings, his visit whilst at the front to a divisional concert party may have been quite appropriate. The Duds (shown in the image below) was the concert party of the 17th (Northern) Division. This image enabled the identification of the general who accompanied him on the visit to be established as Maj-Gen Philip Robertson, who was GOC of the 17th Division (Q2810).[3]

More images of Bottomley's visit to the front show Bottomley coming out of the cathedral at Arras (Q2811) (this must have been taken at the same time as Q2799) and British soldiers [waving to] Horatio Bottomley at Arras (Q2812).

A final group of images show him in a formal pose with a group of staff officers (Q3937, Q3938) and being driven around the destroyed town of Arras (Q3939 and Q3940)

One image from this visit to the battlefields that seems not to have made it into the IWM collection is one in which we see Bottomley and Houston in a cemetery looking at a number of graves.

Above: Bottomley and Houston in what is reported as Etaples Cemetery.

Although it may be apocryphal, it is said that on the tour of the lines Bottomley was soon perspiring in his tin helmet. 'Shell Hole on the right' he was warned. A little further came the message 'barbed wire'. Further on still 'Dead Horse' was given as a warning. 'How far are we from the Germans', Bottomley asked, to which he was given the reply 'About forty miles'.

After the war

Once again he helped the Government. In January 1919 he was asked, in his self-appointed position as 'Soldiers' Friend', to help calm the feelings of troops in Folkestone and Calais who were in a state of near-mutiny over delays in their demobilisation.

Evidence of his speaking to vast crowds after the war can be seen via a British Pathé clip, a still from this can be seen below. (To view the silent 'movie' of Bottomley at Yarmouth in 1919 - which is little over a minute in length, click on this link: Bottomley at Yarmouth | British Pathé )

Bottomley continued his journalism: on 11 November 1920 the Daily Mirror commissioned him to cover the Unknown Warrior ceremony. He wrote: “It was during that awful silence – when the world stood still – that I heard that voice from Heaven, telling me to write.”

At the end of hostilities, the Government issued new 'War Savings Certificates'. Bottomley created a 'scheme' which he advertised in John Bull in which he encouraged the public to send money in for him to purchase these certificates and then draw prizes to be distributed to lucky winners. The scheme was massively over-subscribed and rather than the £50,000 he had set out to receive, nearly double this amount came in. Although the winning numbers were published in John Bull, no names were detailed.

Bottomley’s profits from this scheme and his wartime speaking tours made him another fortune and enabled him - at the end of the war - to be discharged from bankruptcy and thus able to stand for parliament again. In the General Election of 1918 (which was held within a month of the Armistice, on Saturday, 14 December 1918) he fought as an independent for his old constituency of Hackney South under the slogan "Bottomley, Brains and Business". He won with a majority of over 8,000 with almost 80 per cent of the votes cast.

Another Government bond - which was issued in 1919 - was something called 'Victory Bonds'. These were priced at £5 (more than £200 today).

This was, said Bottomley, unaffordable for the working classes, which was probably true. In order to make these more affordable, within the pages of John Bull, he stated he intended to block purchase bonds, then divide them and offer readers the chance to buy a £1 stake. This further 'scheme' was pushed on the public by Bottomley in July 1919 as shown in the illustration below.

Above: John Bull advertises Bottomley's 'Victory Bonds' scheme, 12 July 1919

On the face of it this would have made these more affordable. Inevitably, the scheme was popular and money flooded in - at the peak at the rate of £100,000 per day. He had a small staff of just twelve clerks working on the administration, but they were overwhelmed. The clerks were ex-servicemen who had no experience, and the matching of applications to certificates and record-keeping generally collapsed in chaos. The certificates were easy to forge and within a short space of time these forged certificates were changing hands in pubs.

Above: An example of the Victory Bond Club certificates that were issued. The address is Bottomley's flat

Despite, or because of, the confusion another scheme was set up called the 'Thrift Prize Bond Club' which was supposed to invest in French Government bonds. Slowly, the truth started to leak out in rival newspapers and magazines.

Not surprisingly a lot of the money went straight to Bottomley. Reuben Bigland, who had crossed paths with Bottomley previously, published a pamphlet exposing all of this and Bottomley sued him for libel, which was a mistake as this brought the ‘scheme’ to the attention of the authorities. Bigland was cleared of Libel which then meant Bottomley was exposed - and his 'house of cards' was to come crashing down in the resultant court case which was heard in 1922.

Above: Bottomley leaving the Old Bailey in 1922

Court case and jail

As the case was beginning, Bottomley obtained the agreement of the prosecuting counsel to a 15-minute adjournment each day so that Bottomley could drink a pint of champagne “for medicinal purposes”.

He also asked, privately, for the prosecution not to name 'a certain lady' who had received £1,000 from the scheme. That 'lady' was Peggy Primrose. The prosecuting barrister chivalrously agreed to this and Peggy's name did not come up.

The proceedings brought about a slew of claims from his creditors, and his flat at King Street was soon emptied as his possessions were seized. He was left with a small bed, and was forced to borrow a small table and chairs. Nevertheless, he remained convinced he'd once again be cleared.

In the trial, which commenced at the Old Bailey on 19 May 1922, he was faced twenty four charges of fraudulently converting to his own use sums of money entrusted to him by members of the public for investment in the Victory Bond Club, the War Stock Combination, the Thrift Prize Bond Club and the Victory Club Derby Sweepstake of 1920. The amounts involved totalled £170,000. (£8 million today).

The prosecution brought forward evidence that he used Victory Bonds Club funds to finance various business ventures, pay off private debts and support his expensive lifestyle.[4]

One of the sums drawn from the money raised, which amounted to £41,500 was to purchase two newspapers, the National News and the Sunday Evening Telegraph. Both of these were loss-making and continued to lose money for Bottomley after he had bought them.

The prosecution detailed where some of the money had gone: £5,000 for the upkeep of his horses at Ostend in Belgium and £1,000 on champagne and £15,000 to buy the German submarine the Deutschland which had been purchased in order to take to various ports around the UK for members of the public to visit for a fee. (This idea was another loss-making venture).

Above: John Bull advertising the Deutschland as a 'tourist attraction'

As usual Bottomley defended himself, and claimed that his legitimate expenses in connection with the club, and repayments made to Victory Bonds Club members, exceeded total receipts by at least £50,000. However, the amount of evidence suggested otherwise; the jury required less than half an hour to convict him on all but one of the charges and was given seven years in jail, with hard labour. His appeal was rejected and he was expelled from the House of Commons.

He was 62 years old and unfit to face the rigours of prison life. He weighed seventeen stone and the warders were unable to find a prison uniform to fit him. His wife, Eliza and daughter, Florence came to visit him. At first he could hardly eat and suffered from insomnia. As an alcoholic he was now faced with the shock of total abstinence. An appeal against the verdict was made (his loyal secretary Henry Houston struggled to raise money for his appeal) but even though enough was raised, the appeal failed and his conviction and sentence were confirmed.

Some of the prisoners were ex-soldiers and the fact that they had received parcels from John Bull ensured they were sympathetically inclined towards Bottomley. He became a popular 'celebrity' in prison and was approached by a newspaper for his story. He managed to smuggle a manuscript out of the prison which was published in Lloyds Sunday News.

Some of his ebullience returned. As he sat stitching mailbags in Wormwood Scrubs, a visitor observed: “Sewing, Horatio?” Bottomley replied, “No, reaping.”

The conviction led, inevitably, to another Bankruptcy Order being made against him - this was the third time he was made bankrupt.

Release from prison and death

A year into his sentence he was transferred to Maidstone Prison (where he acquired the nick-name 'John' after the John Bull magazine). After serving a total of five years, the Home Secretary, William Joynson-Hicks, agreed to his early release due to his good behaviour. But even this became complicated. The authorities were concerned about the publicity the announcement of his release would bring about, so his early release date of August 1927 was secretly put into effect sooner than planned. Bottomley was released from Maidstone in on 28 July 1927, much to his annoyance. He at first refused to be released and only consented after being given a good breakfast. He stated he would - during his journey back to the Dicker - hang out of the car window to announce his release, but this wild idea was firmly vetoed by the prison Governor.

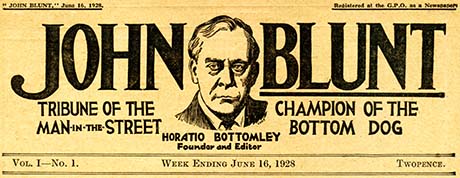

Bottomley tried to resurrect the success he had with John Bull by launching another magazine, John Blunt, in 1928. His few remaining friends and Peggy Primrose tried to dissuade him from this project, but he was determined to make the attempt. He recruited many of the staff who had worked for him on John Bull. Renting expensive offices he launched the new magazine on 16 June 1928, with many of the same features that had appeared in John Bull - this included his column 'The World, the Flesh and the Devil.' But the paper was a shadow of what had gone before, and the readership had moved on. Advertisers did not come forward and the last weekly issue was dated 14 September 1929. He announced he was going on a world tour but was really a devise to mask the move to a monthly edition.

Above: The first issue of Horatio Bottomley's John Blunt magazine, dated 16 June 1928

Around this time he turned on his secretary, Henry Houston and won a court case for libel against him. Debts mounted, the world tour commenced in South Africa but no one was interested in hearing what he had to say. He returned home and shortly after his return, in February 1930, his wife Eliza died.

Faced with mounting debts, and with the failure of John Blunt, he became bankrupt for a fourth time. His mansion the Dicker (which he had previously transferred to his son in law prior to an earlier bankruptcy) was lost (his daughter had divorced so his now 'ex-' son in law had no qualms about selling the Dicker to recover debts) and so he became homeless.

Peggy Primrose, took him to live at her London flat and attempted to organise a lecture tour of the English provinces, but he was banned by most towns. With no income, he was reduced to telling anecdotes of his life at Soho’s Windmill Theatre.

Above: Although indistinct, this shows Horatio Bottomley on stage at the Windmill Theatre. (Ancestry family tree)

After only a few nights at the Windmill, he collapsed on stage with a heart attack. Although recovering from this, Bottomley collapsed again a few months later and was taken to the Middlesex Hospital in London, suffering from cerebral thrombosis caused by arteriosclerosis, where he died at the age of 73 on 26th May 1933. His obituary stated: "What opportunities he had, but how sadly they were wasted! He might have been almost anything, but for one fatal defect."

Above: Details of Bottomley's funeral in the Hull Daily Mail of 31 May 1933

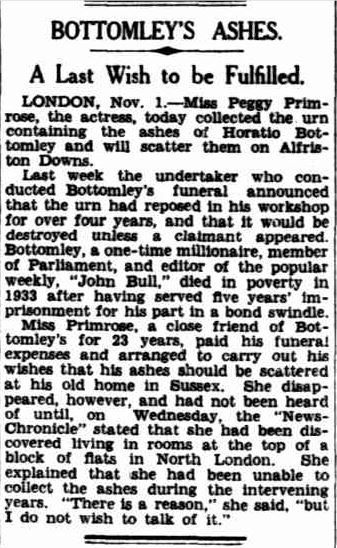

In his will, he requested his ashes to be scattered on the gallops where the horses trained at Alfriston, near his mansion at Upper Dicker near Eastbourne. No-one collected the urn for four years until, in 1937, his nephew, Bertie Dollman, and Peggy Primrose drove to Sussex and carried out his last wish.

Above: Article in the Western Australian, 2 November 1937 (Trove) and a photo in the Daily Mirror 3 November 1937 (Ancestry: Dollman Family Tree)

Conclusion

Without doubt, Horatio Bottomley was a crook, with few redeeming virtues. He did, however, support soldiers and sailors with parcels and was - with his gift of public speaking - a very able recruiter. To an extent he had tried to 'turn over a new leaf' at the outbreak of the war but he was addicted to spending money and the only way to fuel the addiction was to generate vast income from his numerous scams. The Victory Bond scheme was terribly administered, and would likely have collapsed even if he had not syphoned money off for his debts and other projects.

As a media mogul and a builder of a corrupt network of companies he stands comparison with Robert Maxwell, but unlike Maxwell, the house of cards he built came crashing down whilst he remained alive.

Peggy Primrose died in October 1956.

Article by David Tattersfield

Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association

Footnotes

[1] Peggy Primrose's real name was May Esther Fitzmaurice. Born in 1890 into a wealthy family, she married in 1908 Edward Aubrey Courtauld Lowe on 2 September 1908 when she was 18 years old. They divorced in 1913.

Peggy had three brothers, two of whom lost their lives in the war. Private Cecil Fitzmaurice, Army Service Corps, died on 3 May 1915, aged 19. Lt Archibald Fitzmaurice (formerly 16th Lancers and Somali Camel Corps) was serving with Number 1 Squadron RFC when killed on 12 March 1918 whilst in a dogfight with four enemy aircraft.

[2] 'The General' is unnamed, but in view of clues within another photograph is known to be Maj-Gen Philp Robertson, GOC 17th (Northern) Division

[3] My thanks to Prof John Bourne for this identification.

[4] Police records indicate where some of the money ended up: Bottomley’s horse trainer received £1,000, a further £4,800 went to Peggy Primrose, with over £31,000 (nearly £1.5 million today) going to a woman called Laura Rogers, whom the Police believed was another of his mistresses. They noted that she had recently given birth.

Further Reading:

There is further detail about the raising of money to fund the war in this article: The First World War Paid Off?

Books about Bottomley

Very few books are in print detailing Bottomley's life story. Perhaps the best is The rise and fall of Horatio Bottomley: the biography of a swindler by Alan Hyman. This was published in 1972 and can be found online at Internet Archive.

Others include

Bigland, Reuben Horatio Bottomley (1922) [Bigland was the person who - more than anyone else - brought Bottomley down]

'Tenax' The Rise and Fall of Horatio Bottomley (1933) [Tenax meaning ‘The persistent one’ was the pseudonym of Edward Bell, Bigland's solicitor]

Houston, Henry The Real Horatio Bottomley (1923) [Houston was Bottomley's loyal secretary for many years]

Additional Sources:

Dollman Family Tree (Ancestry.co.uk)