In praise of a Colonel and a Lance Corporal. The Advance of 9th Battalion Cheshire Regiment (part of 19th [Western] Division) in the Battle of Messines 7 June 1917 by Peter Crook

- Home

- World War I Articles

- In praise of a Colonel and a Lance Corporal. The Advance of 9th Battalion Cheshire Regiment (part of 19th [Western] Division) in the Battle of Messines 7 June 1917 by Peter Crook

As far as some Colonels were concerned, the writing of their Battalion War Diaries was regarded as an unwelcome bureaucratic exercise although they provided necessary information which would be passed up the chain of command. The entries in their War Diaries, obligatory because of a Field Service Regulation, had to be signed off by them, or a senior officer such as the Adjutant. The pen-on-paper writing could be delegated to a subordinate – and sometimes to junior Subalterns. Occasionally, the choice of writer was apt – Edmund Blunden, for a while, was given the task of writing up the War Diary of 11th Battalion Royal Sussex Regiment because he wrote rapidly, had neat handwriting and expressed himself clearly.

The entries in some War Diaries (each page headed ‘WAR DIARY or INTELLIGENCE SUMMARY’) are perfunctory and minimally informative – enough to satisfy the requirements of the Brigade and Divisional Staff. At times, of course, when advances were under way and when German attacks descended on the British, the nominated Diary writers had other (and they might have argued, better) things to do. Sometimes, after a particularly disastrous event, it might be difficult to find a surviving officer to write up the Diary – and if there were one, he might not have much idea of the details of what had happened. In any case, even in ‘quiet’ times junior officers had little or no idea of ‘the big picture’. And there are mistakes, including errors of dating and timing which can only be corrected by reading the entries in the War Diaries of neighbouring battalions in the same Brigade or Division. Some of these, doubtless, were caused by extreme stress in the battlefield situation.

So, it is rewarding to read the War Diary of 9th Battalion Cheshire Regiment signed off by Colonel R B Worgan. Entries are clearly expressed and there is much useful detail. Colonel Worgan, evidently, was a good commander, always aware of the battlefield situation and often going ‘over the top’ with his men – as he did in the Battle of Messines.

The commendation of Colonel Worgan and 9th Battalion at the Battle of Messines by Colonel Arthur Crookenden in his ‘History of the Cheshire Regiment in the Great War’ was well-deserved.

Background

The Battle of Messines was the first decisive victory the British army could claim after nearly three years of war. It was part of Haig’s plan to drive the German army off the ridge which ran to the east and south-east of Ypres. If the plan worked, and the German army was deprived of its commanding view of Ypres then it might be possible to make a breakthrough leading to the general defeat of the German army.

The Germans knew that the British were tunnelling under their positions on the Messines Ridge and dug their own tunnels to try to find the British tunnels and destroy them. However, because of strict secrecy on the part of the British and the extreme depth of the British tunnels the Germans did not appreciate the scale of British preparations for the attack. Consequently, the attack was a surprise in its form and intensity (3,561,530 shells were also fired 1) and the Messines Ridge was quickly captured with (by the standards of the day) minimal casualties for the British. Most British casualties were suffered in the follow-up attacks in the days following the capture of the Ridge. By 12 June total British casualties amounted to 20,940 (killed and wounded) i.e. slightly fewer than 10% of all the troops involved 2. This figure, however, worried General Plumer who had hoped it would be much lower. It was clear that the next part of the campaign to throw the German army off the northern part of the Ridge (to become known as the Battle of Passchendaele), given the absence of mines under the German positions and the obvious preparations being made, would not be a pushover. In the event, probably over a quarter of a million casualties were suffered in this latter battle – many among the two Irish Divisions (16th & 36th) that had fought in the Battle of Messines.

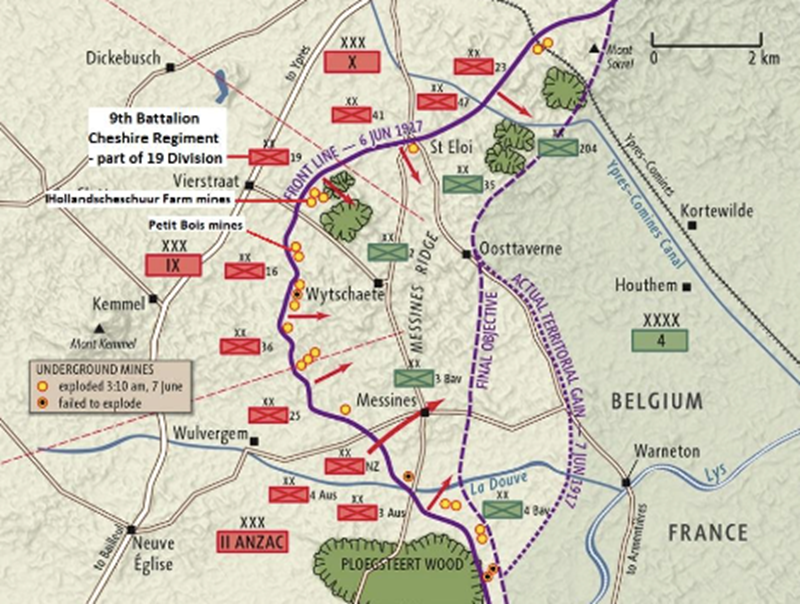

Battle of Messines 1917

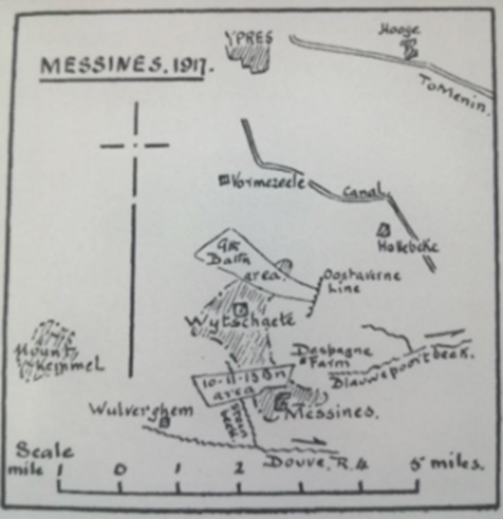

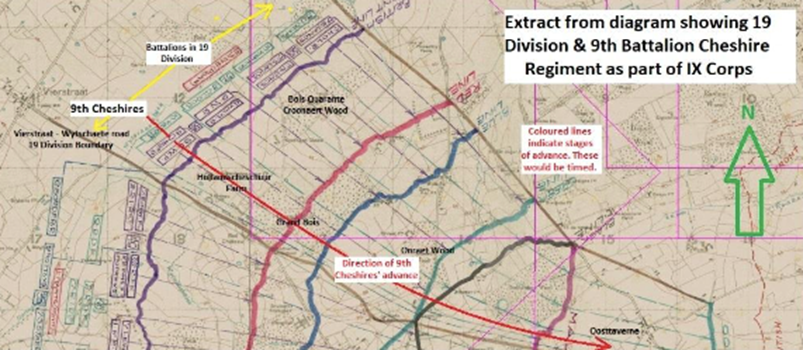

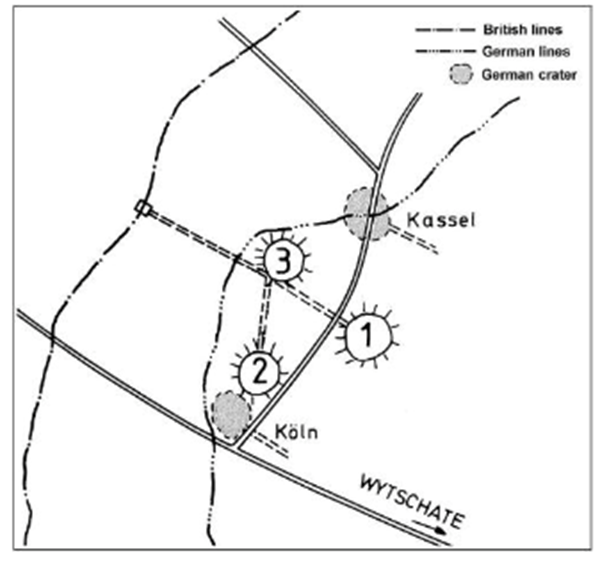

19 Division advanced ESE towards Croonaert Wood (Bois Quarante) and Grand Bois from their lines north of the Vierstraat to Wytschaete road. 9th Battalion Cheshire Regiment was on the right-hand flank of the Division. (See centre of sketch map below from the History of the Cheshire Regiment in the Great War 3 and ‘Extract from diagram showing 19 Division and 9th Battalion Cheshire Regiment as part of IX Corps’).

A summary of Colonel Crookenden’s account in his History of the Cheshire Regiment in the Great War: 4

The Battalion had paid daily visits to a scale model of their objectives.

They went over the top at 03.10 (when the mines exploded) on 7 June led by Colonel R B Worgan and reached their first objective at 04.50.

There was a two-hour halt for consolidation.

At 06.50 the advance continued to a line near Oosttaverne.

During the ensuing days enemy shellfire increased in intensity and caused casualties.

Crookenden: ‘…. The battle was a perfect example of cooperation of all arms and services to a common end.’ The engagement of The Regiment ‘... in so successful an operation made this one of the red-letter days in the story of The Regiment. Their dash, discipline and determination could not have been bettered by any troops.’ 5

The Official History reports that the advance of 19th Division, which included 9th Cheshires, into ‘…. the shattered remains of two woods, Grand Bois and Bois Quarante’ (Croonaert Wood) was ‘helped by the successful explosion of the three mines at Hollandscheschuur to overrun the difficult salient known as ‘Nag’s Nose.’ (‘Gunther’ to the Germans – see sketch map and details below) ‘…. The divisional diary states that ‘there was little resistance from the Germans, who either ran forward to surrender, or, if they could do so, ran away; very few of them put up a fight.’ 6

The illustration below shows clearly the advance of 9th Cheshires on 7 June 1917.

Extracts from 9th Battalion Cheshire Regiment War Diary signed off by Colonel R B Worgan

O/C 9th Battalion Cheshire Regiment:

Slight errors of spelling and grammar have been removed. Timings a.m./p.m. have been retained.

7 June

‘….. At Zero hour the mines went up and our barrage opened. Almost immediately the enemy commenced to shell our assembly positions. No damage was caused however, until our advance from the assembly commenced at 3-30 am when 2Lt. F. B. GADSON, commanding “D” Coy, and about 15 other ranks of “B” & “D” Coys were killed.’

(a.m. 4.45) ‘Battn. H. Q. reached the RED LINE …. The advance was going well. There was little hostile shelling. As the advance through GRAND BOIS progressed, more and more sections got lost, and by the time the barrage had reached the BLUE LINE there were many gaps. These were filled by the second wave …. A good many Germans were killed and wounded with the bayonet and many more were sent back as prisoners …. The capture of the BLUE LINE was not reported until 5-33 a.m. …. About 5-15 a.m. the Commanding Officer left …. The RED LINE to reconnoitre …. He then considered that owing to the loss of direction in the wood, the front companies would be too thin to continue the advance to the GREEN LINE in two waves. Accordingly he reorganised the companies. “A” and “B” leading were to attack in one wave, whilst “D” continued its task of mopping (up). During the two hours halt on the BLUE LINE, consolidation was carried on rigorously …. ‘

(a.m. 6.50) ‘The mist of the early morning had now risen and the advance from the BLUE LINE was begun in the sunshine ….’

(a.m. 7.20) ‘The GREEN LINE was taken at schedule time …. The left of our front line and ONRAET WOOD were shelled intermittently during the morning but very little damage was done & no casualties caused …. The work of consolidation & communication went on without interruption from the enemy, who had ceased to shell our area. Water and rations were brought up by the pack mule train during the morning ….’

At 2.55 pm the Battalion relieved troops ahead of them in the BLACK LINE.

At 9.40 pm orders were received to send a carrying party with supplies to the OOSTTAVERNE LINE.

8 June

In the afternoon “D” Company which had reached the MAUVE LINE was withdrawn to the BLACK LINE.

‘The situation during the day had been comparatively quiet. A certain amount of shelling was reported in the morning, but things became quiet in the afternoon.’

After enemy shelling at 9.10 pm. ‘Our artillery immediately opened a protective barrage …. After an hour’s artillery fire the situation became quiet again.’

At 5.10 pm on 8 June Orders were received that the Battalion would be relieved and withdrawn to Bois Carré, just over a kilometre ENE of Vierstraat and now safely behind the old British front line.

Doubtless, Colonel Worgan would have been relieved to report that casualties for 7 and 8 June were fewer than anticipated: 1 officer and 34 men killed; 3 officers and 120 men wounded; none missing.

The account of Lance Corporal Shepherd, ‘D’ Company, 9th Battalion Cheshire Regiment:

‘The time was exactly ten minutes past three when I gazed ahead to witness the great upheaval. A sheet of flame shot aloft to an immense height – a monstrous curtain of crimson drawn up suddenly along the whole crest crowned with foaming black smoke. To our dazzled eyes it seemed to hang there for several seconds while our trench rocked with the reaction ….

I can see them now, rising from the twisted network of branches and bursting forth from fresh green leaves, thirty or forty faces grey with fear and great staring eyes from which the light of reason seemed to have been driven …. and they appeared before us with a forest of upthrown hands. Some cried out and gesticulated, some threw themselves down and grovelled at our feet. It was a terrible and unnerving sight.’

I first heard this account read by an actor in the video ‘Ypres’, one of the ‘Great Battles of the Great War’ series. This was produced by Ed Skelding Productions for Tyne Tees Television in the 1990’s and is now in DVD format.

Eloquent, and almost biblical in tone, this is a powerful statement from one of the ‘other ranks’ about the explosion of the mines at Messines, the advance on 7 June 1917 and the effect on German soldiers.

Frankly, because of its very power and eloquence, I had been somewhat sceptical about the authenticity of this account. However, recently, I managed to contact Ed Skelding and he was able to assure me of the sound provenance of Lance Corporal Shepherd’s account. Later in 1917 Lance Corporal Shepherd was wounded – it was a ‘Blighty one’ and he ended up in Queen Mary’s Military Hospital, Whalley, in Lancashire. There, in October 1917, he made notes of his experiences in the war and from these came the account of 9thCheshires’ attack near Messines. His written reminiscences passed into the hands of a relative whose name and address Ed Skelding was able to supply. It was while researching the Salient for the making of the video in the 1990’s Lance Corporal Shepherd’s account was presented to him.

Lance Corporal Shepherd writes of reaching one of the three mine craters at Hollandscheschuur Farm: ‘I saw down on my left the red fuming earth sloping sharply to a pit of blue incandescence, writhing and seething in that horrid depth. The exhalation of the pit wrapped us round with deadly vapours and we lurched giddily away from the danger ….’

‘Grand Bois had felt the weight of the British guns, and was thinned out to tall bare poles …. As we advanced slowly through the battered woodland the German barrage fell upon us …. Inky founts spirited (sic) from the battered ground, shrapnel rent the air overhead with a sound like the tearing of calico, and now and then the bare trunk of a tree wheeled over like a giant’s club to smite the earth …. And again and again there descended on our backs and helmets showers of clods, turf and small pebbles ….’

Emerging from Grand Bois Lance Corporal Shepherd was able to see the impact of the British barrage ahead of him and his comrades ‘…. thundering down like a long wave rearing its crest but never breaking. It would be difficult to describe the strange upheavals, the amazing contortions, and the evil squirmings going on in that closely packed line of smoke …. Rearing and rolling and ever changing. But throughout it kept its hammering roar which deafened us where we stood four hundred yards away.’

Lance Corporal Shepherd records his dismay at his Sergeant shooting a German soldier running away. ‘Yet the man was escaping and would speedily have been among his friends, where he could well have manned a rifle or machine gun against us. There are no ethics in war.’

The encounter with the surrendering German soldiers was, he wrote, in ‘Onret Wood’ (correctly spelled Onraet Wood – see map above, slightly below centre).

Lance Corporal Shepherd did not feel any relief or elation at having survived the battle – rather ‘a sense of hopelessness of the future and the feeling of helplessness that accompanied it. It was, I suppose, the terrible but inevitable fire-baptism of a sensitive mind and it is more common, perhaps, than I have realised.’

L/C Shepherd's account is a treasure. One of those 'golden keys' all historians look for to unlock the past. He wrote the notes which wer made up into his account in the military hospital in Whalley.

‘During the First World War, the 2,000 bed Queen Mary's Military Hospital was housed in the County Asylum at Whalley, remaining there until June 1920. The Military Cemetery associated with the hospital is at the eastern end of what was known at the time as the Mental Hospital Cemetery and was handed over to the War Department in February 1916. The cemetery has a Cross of Sacrifice and there is also a memorial to all the servicemen, nearly 300 of them, who died in the Hospital.

The Military Cemetery contains 33 First World War burials and nine from the Second World War.’ (From the CWGC website.)

Perhaps I should not have been surprised at the large number of soldiers who died in the hospital. I presume that those not buried in the nearby military cemetery were 'repatriated' to their next of kin and buried in cemeteries of their choice

I also presume that Lance Corporal Shepherd was wounded in the Third Battle of Ypres. 19th Division* (of which 9th Cheshires was a part) was heavily involved in the Battles of the Menin Road Ridge 20-25 September; Polygon Wood 26 September - 3 October; Broodseinde 4 October; Poelcapelle 9 October; First Battle of Passchendaele 12 October. Having been seriously wounded in any one of these battles would account for Lance Corporal Shepherd being in the hospital at Whalley in October. (19th Division was also involved in the Second Battle of Passchendaele beginning on 26 October - but I think that would have been too late for him to have recovered sufficiently to write those notes in hospital in October. I doubt, in any case, that he would have reached Whalley before the end of the month.)

It is probable that Lance Corporal Shepherd was suffering 'shell-shock' and I think it is possible that he wrote his account as a form of therapy. What we might now call 'talking therapy' and ‘writing therapy’ was for 'officers only' and only in some hospitals (though some argue this is a crude misrepresentation) - Sassoon and Owen were lucky to be at Craiglockhart. Lance Corporal Shepherd, and perhaps some of his comrades, had to engage in self-administered 'writing therapy' instead - yet who really knows? Queen Mary's Hospital was, after all, housed in the County Asylum at Whalley and there may have been sympathetic/empathetic medical officers there.

I have been unable to find Lance Corporal Shepherd's service record. It may have been one of the many destroyed during the Blitz in September 1940. However, there is a medal card indicating the award of the Military Medal for: Pte (A/L/C) E C Shepherd, Depot late 9th Bn Ches R, Regimental Number 51002, Date of Gazette 12.12.17. This award is noted in Crookenden’s History of the Cheshire Regiment in the Great War in the list of Individual Honours but there are no details. (Curiously, Colonel Worgan is listed only as ‘Mention’ i.e. ‘Mentioned in Despatches’, whereas, in fact, he was Gazetted DSO in January 1917.)

Lance Corporal Shepherd survived the war.

*19th Division lost well over 39,000 casualties during the war.

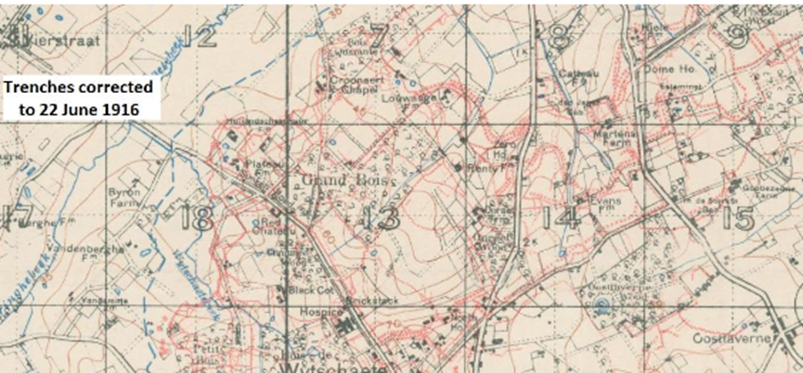

9th Cheshires advanced towards Hollandscheschuur Farm and Grand Bois:

Hollandscheschuur Farm mines 7

In November 1915, the 250th Tunnelling Company began work on the deep mine at Hollandscheschuur Farm as it sank a shaft to some 20 m (66 ft) and then drove a tunnel over 250 m (820 ft) extending well behind the German lines. Despite counter-mining by German units (see sketch map above), three charges were eventually placed and fired.

The mine consisted of three chambers (Hollandscheschuur Farm Charges 1–3) with a shared gallery. It was placed around the German strongpoint Gunther between Wijtschaete and Voormezele, not far from the Bayernwald trenches in Croonaert Wood.

Charge 1 34,200 lb (15,500 k)

Charge 2 14,900 lb (6,800 k)

Charge 3 17,500 lb (7,900 k)

The explosive used was Ammonal. The composition of ammonal used at Messines was 65% ammonium nitrate, 17% aluminium powder, 15% trinitrotoluene (TNT), and 3% charcoal. The Ammonal was contained within soldered metal cans or rubberised bags to prevent penetration of moisture into the ammonium nitrate which would have stopped it exploding.

Footnote on Colonel Worgan: He had been a Major in the 20th Deccan Horse, Indian Army, which arrived at Marseilles in September 1914. In January 1916 he was detached from the regiment and, as a temporary Lieutenant Colonel, was given command of 9th Battalion, Cheshire Regiment at the age of only 34. The Battalion was engaged in action in the Battle of the Somme from 2 July 1916 at La Boisselle and then at High Wood, Pozières, Ancre Heights and Grandcourt. Colonel Worgan remained in command of 9th Cheshires until October of 1917 when, promoted to temporary Brigadier General (though still only having the permanent rank of Major!), he took command of 173rd Brigade. 173 Brigade was heavily involved in the Second Battle of Passchendaele then suffered severe casualties during the last German advance in 1918. After the war Brigadier General Worgan returned to India. He was Military Secretary to Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught during his tour of India, between 1920 and 1921, Military Secretary to the Prince of Wales during his tour of India, between 1921 and 1922, and Military Secretary to the Viceroy of India, between 1923 and 1926. He was Commander of the Southern Brigade Area, between 1926 and 1930. In 1930, at the age of 49, he retired from the British Indian Army with the honorary rank of Brigadier General and (with his Colonel’s pension supplemented by a private income?) settled in London in an apartment in fashionable Pall Mall. Appropriately, given his past career, he was made one of His Majesty’s Bodyguard of the Honourable Corps of Gentlemen-at-Arms. But this honour was only briefly held. Brigadier General Worgan died on the 6th February 1934 at the early age of 52.

References

1 Official History - Military Operations France and Belgium 1917 Vol II. Pub. HMSO 1948. Page 49.

2 Ian Passingham - Pillars of Fire – The Battle of Messines Ridge June 1917. Pub. Sutton 1998. Page 162.

3 Colonel Arthur Crookenden - History of the Cheshire Regiment in the Great War. Pub. W H Evans, Sons & Co. Ltd. 1939. Page 186, Kindle Edition font size 1.

4 Ibid. Page 188.

5 Ibid. Page 189.

6 Op. cit. Official History. Page 59.

7 Sketchmaps based on the plans published in Roger Lampaert - De Mijnenoorlog in Vlaanderen 1914–1918. Pub. Roesbrugge/Belgium (Drukkerij Schoonaert) 1989 and Peter Barton/Peter Doyle/Johan Vandewalle - Beneath Flanders Fields: The Tunnellers' War 1914-1918. Pub. Staplehurst (Spellmount) 2005. Pages 109 and 193. Further information: Pages 166-7; 192.

Many thanks to:

Major John Ellis (Retd.) former curator of the Cheshire Military Museum.

Major Tony Astle (Retd.) formerly of the Cheshire Regiment.

Caroline Chamberlain, Museum Officer, Cheshire Military Museum, for granting me access to the War Diary entries of 9th Battalion Cheshire Regiment for 7 and 8 June 1917.

Ed Skelding, who has recently completed a series of ten films in the series ‘Walking the Western Front’ with Nigel Cave for Pen & Sword Publications. These cover the BEF at Mons, Le Cateau and Nery, the First and Second Battles of Ypres, the Campaign on the Somme, the Battle of Messines, and the Third Battle of Ypres. He is also working on a book on the Ypres Salient which will give an account of the lesser-known battles fought there.

Peter Crook

August 2023