‘Kitchener of Khartoum’ and HMS Hampshire : 5 June 1916

- Home

- World War I Articles

- ‘Kitchener of Khartoum’ and HMS Hampshire : 5 June 1916

Within Lyness Royal Naval Cemetery, on the Island of Hoy on the Orkney Islands, is a memorial to the officers and men who were lost on board HMS Hampshire; in addition to the memorial (pictured below) are the graves of 123 men of the Royal Navy who died on 5 June 1916 when the Hampshire went down. For those who regularly visit Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemeteries, it is not uncommon to see ‘clusters’ of deaths around one date. Most of the bodies of the men who were killed were not recovered and most of these men are named on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial.

The memorial to the men from HMS Hampshire in Lyness Royal Naval Cemetery

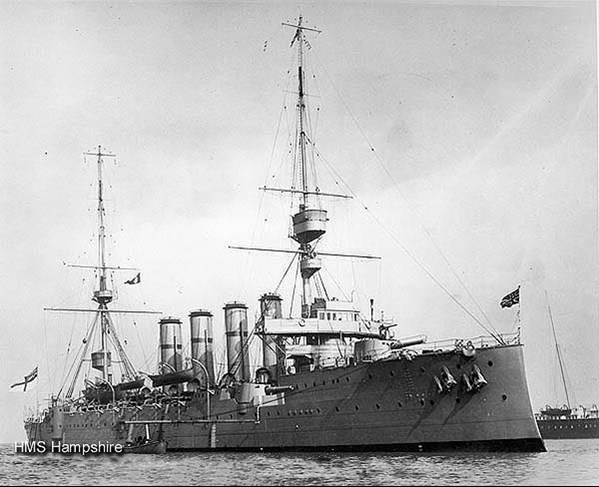

HMS Hampshire

Not all of the casualties at Lyness are from the Royal Navy or Royal Naval Reserve, there are some from the Royal Marines. There was a Royal Marine component on the Hampshire but also, as seen in the image to below, there is one casualty from the Cameron Highlanders.

Above: One of the headstones in Lyness Royal Naval Cemetery is surprisingly a 2/Lt of the Cameron Highlanders.

Why would an officer from the Army be on board this vessel. What is the story?

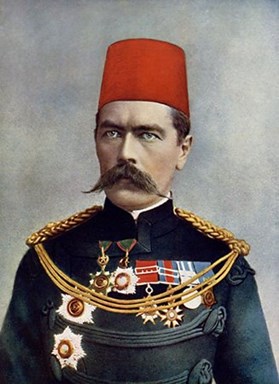

Lord Kitchener

Horatio Herbert Kitchener was born on 24 June 1850 in Ballylongford, County Kerry in Ireland and was educated in Switzerland before going on to the Royal Military Academy in Woolwich (the Army’s ‘school’ for Artillery and Engineer officers).

Having learned Arabic, Kitchener was perhaps a natural choice for a further posting to the British controlled Egyptian Army and was to take part in the failed expedition in 1884 to rescue Major-General Charles Gordon (“Gordon of Khartoum”). Gordon was beheaded by the followers of the self-proclaimed Mahdi, Muhammad Ahmad. It was around this time that Kitchener permanently damaged his eyesight due to the glare of the sun and sandstorms in the deserts of Egypt and Sudan; this led to him having a squint in one eye which was to be almost a ‘trademark’ in future years. In 1874 he was seconded to the Survey of Western Palestine, which involved mapping much of what is now Israel. This was the start of his connection with the East that was to shape his career and, arguably, British policy in the First World War.

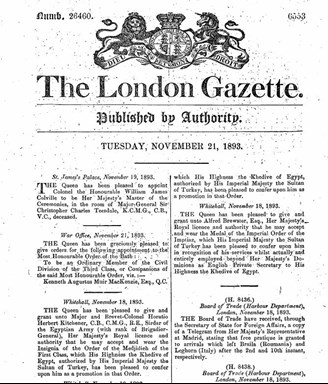

Promoted to the rank of Major, he served as an Intelligence Officer in the Nile Campaign of 1884-85, becoming Governor of the Red Sea Territories. On 17 January 1888 Kitchener was almost killed when he was leading a force in an attack at Handub. Severely wounded in the neck and lower jaw, he continued to direct the skirmish and successfully organised the withdrawal. He was treated for his wounds back in Cairo, but was eventually forced to return to the UK to recuperate. None of this harmed his reputation in the British Press – this popularity no doubt helped him with a series of promotions that was to lead him, in 1892 to the position of Sirdar (or Commander-in-Chief) of the British controlled Egyptian Army. This brought him the rank of Brigadier-General in 1893 at the age of just 43.

Above: Kitchener became Sirdar of the Egyptian Army and the copy of the London Gazette of 1893 announcing Kitchener’s promotion to Brigadier-General.

Kitchener’s popular reputation was sealed in 1898 when he led an army in the defeat of Abdullah al-Taashi, the successor to the Mahdi Muhammad Ahmad, at the Sudanese village of Omdurman (today a suburb of Khartoum) – thus avenging the death of Gordon. Also present at the this battle was a young officer with whom Kitchener was to come into contact later – Winston Churchill. In view of this victory he was awarded the title Baron Kitchener of Khartoum. In an enlightened move, he ordered the mosques of Khartoum to be rebuilt and guaranteed freedom of religion to all citizens of the Sudan.

Further service followed when he acted as Chief of Staff to the Commander in the Boer War, taking overall command in 1900. This was probably his most challenging appointment to date, and the camps which he instituted during the latter stages of the war in order to break the Boer resistance became infamous for their high death rates. Despite this, he was promoted to full General and became Viscount Kitchener.

It was at this time that he appointed as his ADC, a young officer, Lieutenant Frank Maxwell who had just been awarded the Victoria Cross. The citation for Maxwell’s VC reads:

Lieutenant Maxwell was one of three Officers not belonging to "Q" Battery, Royal Horse Artillery, specially mentioned by Lord Roberts as having shown the greatest gallantry, and disregard of danger, in carrying out the self-imposed duty of saving the guns of that Battery during the affair at Korn Spruit on 31st March, 1900.

This Officer went out on five different occasions and assisted to bring in two guns and three limbers, one of which he Captain Humphreys and some Gunners, dragged in by hand. He also went out with Captain Humphreys and Lieutenant Stirling to try to get the last gun in, and remained there till the attempt was abandoned.

Lieutenant (later Brigadier-General) Frank Maxwell, VC

Maxwell was to become a Brigadier-General and was killed in Belgium in 1917. He is buried at Ypres Reservoir Cemetery.

Kitchener’s next appointment was as Commander-in-Chief in India, where he set about modernising the Indian Army – although this brought him into conflict with the Viceroy, Lord Curzon.

Above: Lord Curzon

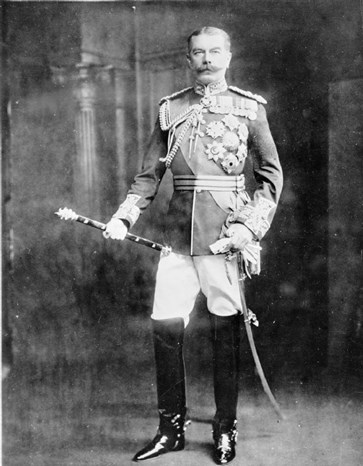

Promoted to Field Marshal in 1910, Kitchener was hoping to me made Viceroy, but political manoeuvring prevented this appointment. Instead, he returned to Egypt in 1911 as Consul-General - in effect ‘ruler’ - of both that country and the Sudan.

Above: Full length portrait of Field Marshal Earl Kitchener of Khartoum, in full dress uniform and carrying his Field Marshal's Baton, taken shortly after being promoted to the rank and before his appointment as British Governor General of Egypt and the Sudan.

In April 1911, whilst Consul-General, Kitchener purchased, for £14,000 (about £1.3 million in today’s money) a magnificent house in Kent called Broome Park.

…almost the whole of Kitchener’s leisure activities for the last five years of his life was devoted to the tasks of beautifying the grounds; of reconstructing the interior of the house which he gutted completely; and of filling it with the treasures which he had managed to accumulate by purchase, gift and loot… [the property also had a] sunken rose-garden where he had personally designed a special fountain embellished with nymphs and sea-monsters…

Philip Magnus, Kitchener: Portrait of an Imperialist (London: J Murray, 1958)

Above: Broome Park today is a golf club

In 1914, Kitchener left Egypt for his summer leave in England, arriving in Dover on 23 June, just days before the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Upon the outbreak of war, the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith took the step of appointing Kitchener Secretary of State for War. Swimming against the prevailing current, Kitchener immediately predicted a long war and saw the need for recruitment into the Army on an unprecedented scale. What followed next did much to shape Britain’s war effort and has probably shaped Britain’s perception of the war ever since.

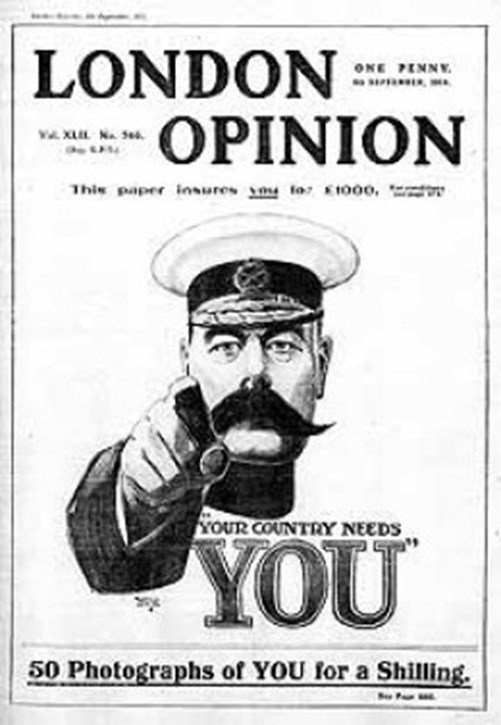

By-passing existing plans for expansion of the Army, Kitchener used his personal prestige to recruit volunteers into New Armies. Posters were plastered throughout the country urging men to join up.

The Prime Ministers, Margot Asquith wife is reported as saying, slightly waspishly that “If Kitchener was not a great man, he was, at least, a great poster”, to which Kitchener is said to have retorted to his personal staff that all his colleagues [i.e. in the cabinet] repeated military secrets to their wives, except Asquith, who repeated them to other people’s wives.

Above: The recruitment poster, designed by Alfred Leete is possibly one of the most iconic images of the 20th Century.

Kitchener was initially successful – he had great vision of the strategic issues and realised that Britain could not (at least initially) compete with the vast armies that Germany and France could put into the field.

Recruiting offices were mobbed by men wanting to join up.

Kitchener’s decision to by-pass the existing structures has been a matter of great debate, but the resultant rapid expansion of the Army ensured Britain was fully committed to the war effort on the continent.

By 1916, however, Kitchener’s autocratic style was irritating politicians and, possibly in a bid to side-line him, he was despatched on a mission to Russia.

After lunching with the King on Saturday 3 June, Kitchener went to Broome with FitzGerald [his Personal Military Secretary] for the night… On the afternoon of Sunday 4 June he motored from Broome to the War Office, where he signed a number of official papers… He then took the night train from King’s Cross to Thurso, on his way to Scapa Flow.

Philip Magnus, Kitchener: Portrait of an Imperialist (London: J Murray, 1958)

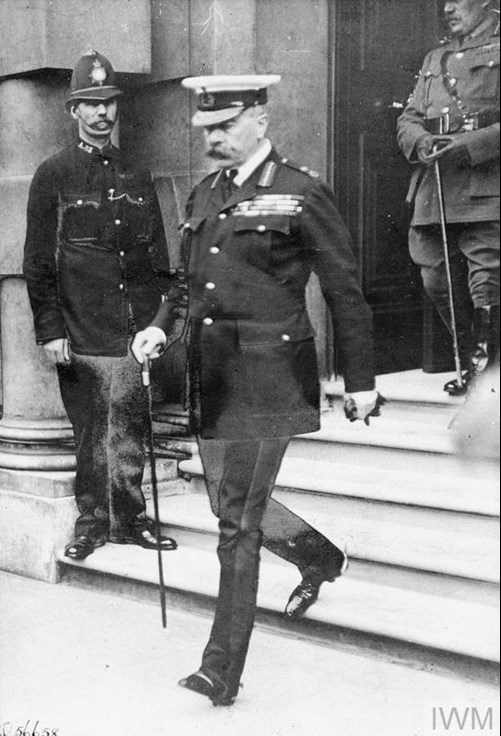

Kitchener leaving the War office just days before his mission to Russia

Arriving at Scapa on 5 June, the party (totalling twelve) prepared to depart. Kitchener met with and had lunch with Admiral Jellicoe, commander of the Grand Fleet who had just fought the Battle of Jutland. Transferring to the cruiser HMS Hampshire, Kitchener dismissed Jellicoe’s suggestion that he delay departure due to the worsening weather. Hampshire set sail at about 5pm, escorted by two destroyers, HMS Unity and HMS Victor. The weather continued to deteriorate, and at 7pm the escorting destroyers were instructed to return to port.

Above: From the Daily Express, 19 February 1935. “Lord Kitchener’s last afternoon alive”.

Hampshire sailed on through waters that hadn’t been swept for mines in over a week. Forty minutes later Hampshire was about a mile and a half off Marwick Head when she struck one of the 34 mines which had been laid by German submarine U-75 the week before.

The stricken vessel listed to starboard, and sank in 15 minutes. 655 men were on board. Only twelve men survived and none were able to give any reliable account of Kitchener’s last movements.

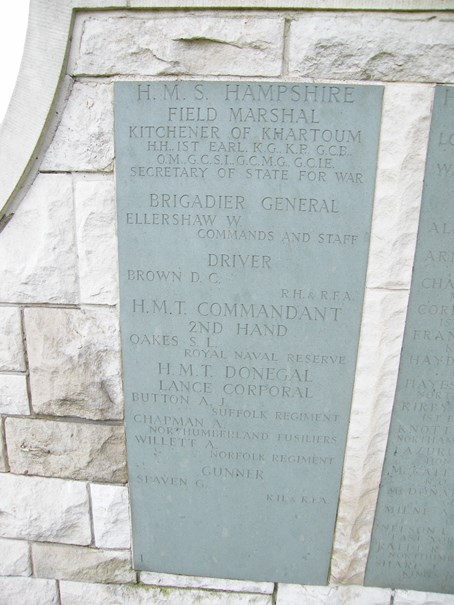

None of the survivors included Kitchener’s party. Relatively few bodies were recovered; 123 are buried at Lyness Royal Naval Cemetery. Of the party bound to Russia, a number (being military personnel) are commemorated by the CWGC.

- Field Marshal The Rt Hon Horatio Herbert Kitchener KG, KP, GCB, OM, GCSI, GCMG, GCIE Secretary of State for War

- Brig-Gen Sir Hay Frederick Donaldson KCB Chief Technical Adviser to the Ministry of Munitions. (This was a temporary commission which had only been granted prior to the trip – presumably to give a better impression to the Russians.)

- Lt-Col Leslie Stephen Robertson Deputy Director of Production at the Ministry of Munitions. (This was again a very recent, temporary commission.)

- Brig-Gen Wilfrid Ellershaw Aide-de-Camp to Lord Kitchener

- Lt-Col O A FitzGerald CMG Kitchener’s Personal Military Secretary

- 2/Lt Robert MacPherson Translator

- Driver David Brown Probably a “batman” to one of the officers

Non Military member of the party were:

- Mr Hugh James O'Beirne CVO CB, British Foreign Office Minister

- Mr L C Rix, Shorthand Clerk to Mr O'Beirne

Two personal servants

- Henry Surguy-Shields

- Walter Gurney

And finally, Kitchener’s personal detective

- Detective Sergeant McLoughlin of Scotland Yard

The panel (below) at the Hollybrook Memorial, Southampton (below) commemorates the military personnel on HMS Hampshire (Brig-Gen Donaldson and Lt Col Robertson are named on the addenda panel at this memorial).

Of Kitchener’s party, only FitzGerald (who is buried at Eastbourne (Ocklynge) Cemetery and 2/Lt MacPherson (mentioned above - and is buried at Lyness) have known graves.

The news of the tragedy was issued via a Press Release:

PRESS BUREAU,

Tuesday, 1.40 p.m.

The Secretary of the Admiralty announces that the following telegram has been received from the Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet at 10.30 (B.S.T.) this morning : —

I have to report with deep regret that his Majesty's ship Hampshire (Captain Herbert J. Savill, R. N.), with Lord Kitchener and his Staff on board, was sunk last night about 8 p.m. to the west of the Orkneys, either by a mine or torpedo.

Four boats were seen by observers on shore to leave the ship. The wind was N. N. W., and heavy seas were running. Patrol vessels and destroyers at once proceeded to the spot, and a party was sent along the coast to search; but only some bodies and a capsized boat have been found up to the present.

As the whole shore has been searched from the seaward, I greatly fear that there is little hope of there being any survivors. No report has yet been received from the search party on shore.H.M.S. Hampshire was on her way to Russia.

The Secretary of the War Office notifies with reference to the announcement of the loss of H. M. S. Hampshire that the special party consisted of Lord Kitchener, with Lieut-Colonel O. A. Fitzgerald, C. M. G., Personal Military Secretary, Brigadier-General W. Ellershaw, Second-Lieut. R. D. Macpherson, 8th Cameron Highlanders., Mr. H. J. O’ Beirne, C. V. O., C. B., or the Foreign Office. Sir H. F. Donaldson, K. C. B., and Mr. L. S. Robertson, of the Ministry of Munitions, Mr. L. C. Rix, shorthand clerk, Detective McLoughlin of Scotland Yard, and the following personal servants:- Henry Surguy-Shields, Walter Gurney and Driver D.C. Brown, RHA, were also attached to the party.

Whilst the was press naturally concentrated on the death of Kitchener, this was one of the largest losses of life in a single incident during the war for the Royal Navy.

Today, the wreck of HMS Hampshire remains a war grave and she lies at around 213 feet off Marwick Head, on the west coast of Orkney. In 1983 a propeller and part of a drive shaft were illegally salvaged, these relics were given to a local museum.

Above: One of the propellers from HMS Hampshire

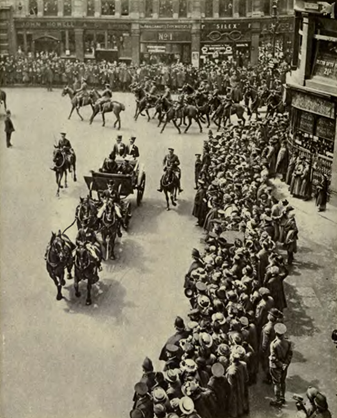

Although a memorial service was held at St Paul’s Cathedral for Lord Kitchener on 13 June 1916, the war moved on.

The Memorial Service for Lord Kitchener.

His role in the supreme direction of the war had already been undermined, and it is possible the removal of Kitchener from the centre of power may have ultimately assisted the British war effort. His influence and decisions continue to be a matter of debate among historians to this day.

Above: The Memorial to Lord Kitchener in St. Paul's Cathedral and The Kitchener Memorial Tower at Marwick Head.

Lord Kitchener and The Western Front Association

Until his death in December 2011, one of the WFA’s Vice Presidents was Kitchener’s great nephew, Henry Herbert Kitchener.

Article by David Tattersfield

Further Reading (two web based site articles about Kitchener)

Did Kitchener's Decision to Raise the New Armies Wreck Pre-War Plans?

Kitchener Biographies and similar works

Peter Simkins - Kitchener's Army: The Raising of the New Armies 1914-1916

Philip Warner - Kitchener: The Man Behind the Legend

George Cassar - Kitchener's War: British Strategy from 1914 to 1918

John Pollock - Kitchener: "Road to Omdurman" and "Saviour of the Realm"