Lanoe Hawker, VC: Pilot, Innovator and Inventor

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Lanoe Hawker, VC: Pilot, Innovator and Inventor

Lanoe Hawker was born on 31 December 1890 in Longparish, Hampshire, and soon showed himself to be an intelligent boy. At the age of ten he went to Geneva with his younger brother for schooling; with Lanoe returning to England two years later. In 1905 he decided to join the Royal Navy and successfully entered the Britannia Naval College at Dartmouth. He was a promising cadet but contracted a chill, then jaundice, and by not reporting sick early enough he strained his heart, but decided to retire rather than lose seniority while recuperating. While regaining his strength he spent time experimenting with kites and model aeroplanes.

Above: Lanoe Hawker VC, DSO. IWM Q67598

By early 1910 he was fit enough to resume a military career, but this time entered the Royal Military Academy, Woolwich, to train as a Royal Engineer officer. His interest in model aeroplanes continued and he also began to visit airshows. He was a founder member of the Royal Aero Club (RAC), membership of which gave free admission to the Hendon aerodrome where he carefully observed aircraft and pilots and asked many questions. He also flew for the first time as a passenger, thereafter deciding to learn to fly so that he could join the fledgling Royal Flying Corps (RFC). He passed his RAC flying test in March 1913, thereby making him eligible for the RFC. However, he was first posted to Ireland before eventually receiving orders to report to the Central Flying School (CFS) in September 1914. With war on the horizon, he then received orders at the end of July 1914 to report to the CFS immediately. However, a shortage of aircraft meant that he did not pass out from the CFS until early October 1914, having achieved just 25 hours in the air. He was then posted to 6 Squadron which left Farnborough for Dover on 6 October, before crossing the Channel the following day.

While Lanoe Hawker’s name is always associated with his exploits in the air, less well known is his talent for innovation and invention.

Pre-war he had taken out a provisional patent for a differential belt drive for a car which gave a smooth change of gear through increasing or decreasing the effective size of the belt pulleys. This was unsuccessful due to the belts of the day being unable to withstand the stresses, however, this appears to be a similar system to that used on DAF cars some 40 years later.

His next invention was for a variable and reversible engine-driven hydraulic pump to feed high-pressure fluid to hydraulic motors driving the wheels of a car, but he shelved this project when war broke out. Again, similar systems appeared on vehicles many years after he had first worked on the idea.

Once in France, he applied himself to solving problems facing the RFC. After a difficult winter when aircraft were often left out in the elements(Hawker had one aircraft destroyed and another badly damaged by gales), he decided that his latest aircraft should not suffer a similar fate. Putting his Royal Engineer training to good use he designed a wooden aircraft shelter. The first examples were made from hop poles found in the area around the airfield at Bailleul, but using ordinary timber the design was to be seen on most airfields by the end of 1915.

Another early invention was Hawker’s ‘fug boots’, which were thigh length and sheepskin lined to try and ward off the extreme cold at altitude. His first pair was made for him by Harrods, and they went on to be introduced as a standard item of aircrew clothing.

Above: Fug Boots being worn by an unknown Bristol F2B pilot.

In the early days of the war there were no dedicated scout (fighter) aircraft, and when more suitable machines were introduced they were sent in small numbers to the existing squadrons. To arm the scouts various methods were tried and Hawker designed a Lewis gun mounting that was built by one of the mechanics, E.J. Elton. It was mounted on the side of his Bristol Scout’s cockpit and allowed the Lewis gun to be fired obliquely between the wing bracing wires and clear of the propeller. The downfall was that it was difficult to fly the aircraft in one direction while aiming and firing in another, however, Hawker was able to master the problem sufficiently to down three enemy aircraft on the evening of 25 July 1915. The feat was thought so extraordinary that he was awarded the Victoria Cross, the first ever awarded for air combat.

Above: Hawker’s Bristol Scout with Lewis gun mounted on side of cockpit. www.ww1aviationheritagetrust.co.uk

A more conventional position for the Lewis gun was on the upper wing where it could fire over the top of the propeller, however, no matter the manner of its mounting it was hampered by the 47round ammunition drum. With such a limited capacity, just a few seconds of firing in a dogfight would empty it and the pilot then had to replace it while still flying the aircraft and evading the enemy, which was fraught with difficulties. In one extreme example Louis Strange fell from his cockpit while wrestling with a jammed drum (see the article ‘Hang on a Minute!’).

One possible solution was to mount two guns, however, when Hawker presented the idea (it had already been unofficially trialled in his squadron) to his brigade commander he was told to remove the second gun as it was a non-standard fitment and therefore contrary to regulations! Still concerned about the problem, he next worked with W.L. French, a skilled engineer, who had enlisted as a mechanic in the RFC. Together they joined two drums together, and Hawker presented the result to the War Office while on leave in May 1916. Some prototype drums were then manufactured and sent to France where Hawker and French quickly identified some weaknesses and suggested alterations. Subsequently the 97round double drum was to become a standard fitment for airborne versions of the Lewis gun.

Above: Airborne version of the Lewis gun fitted with 97round double drum. Note the canvas handle that made drum changing easier when wearing thick gloves. www.ima-usa.com

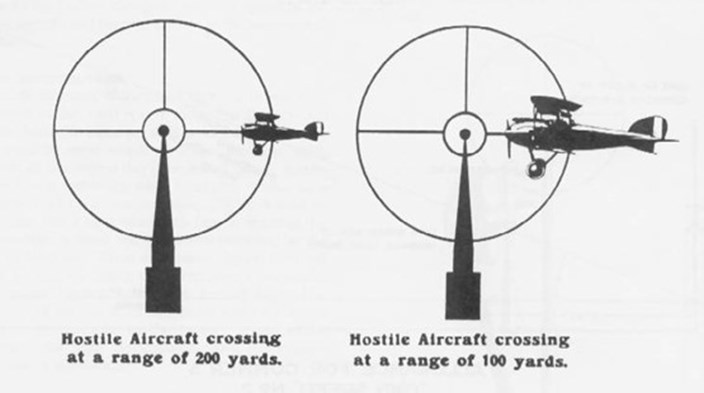

Gun sights also attracted Hawker’s attention. He first designed a sight which allowed for the distance an enemy aircraft would travel in the time his machine gun bullets were in-flight, so-called deflection shooting. He then improved his initial design to become the ring and bead sight, which remained in service for many years.

Above: The ring and bead sight. The bead was centred in the inner ring and the target centred on the edge of the outer ring to give deflection shooting where the target and the fired bullets arrived at the same place at the same time. https://forum.axishistory.com

To use the ring sight required practice so Hawker designed the ‘Forward Aiming Model’ which was apparently a simple device which the pilot could use on the ground to improve his aim. Again, this invention went on to be widely used by the RFC.

This was followed by Hawker’s ‘Rocking Fuselage’, an early form of simulator which was also used widely. Consisting of a dummy section of fuselage with controls and machine gun, it sat on a pivot and was fired at moving targets strung on a wire.

Above: A version of Hawker’s ‘Rocking Fuselage’ gunnery simulator. www.ww1aviationheritagetrust.co.uk

Although these devices helped considerably, Hawker took gunnery training a step further and placed a full size chalk silhouette of a German aircraft on the edge of the airfield. Known as the ‘Boche’ the pilots could practice diving and firing at it, often using up any remaining ammunition when returning from a mission.

Another gun sight invented by Hawker was the ‘Upward Shooting Sight’. He had recognised that it was sometimes possible to approach an enemy aircraft unseen from below, but when firing a machine gun at high angles of elevation the bullets were deflected by the airstream acting against them. Hawker carefully studied the Vickers machine gun range tables and extrapolated them for the very high angles he required, as well as the curves for deflection caused by his forward movement through the air at about 90 m.p.h. His eureka moment came when he saw that one of the curves for trajectory was very similar to one for wind pressure and that it might be possible for one to cancel out the other thereby allowing the bullet to travel in a straight line. The sight allowed the pilot flying below an enemy aircraft in the same direction and at the same speed to adjust the sight to his airspeed. The bullets would then travel about 2,000 feet in a straight line. The invention was considered so secret that it was initially only used in England, and when later introduced in France it was only used by selected pilots flying behind British lines. The Germans could not understand how their aircraft penetrating beyond British lines were being shot down by an aircraft flying below them. The invention remained a secret for many years but was likely an inspiration for the ‘Schräge Musik’ upward firing cannon used to devastating effect by German night fighters attacking British bombers in WW2.

Above: A pair of upward firing guns fitted to a Sopwith Dolphin.www.ilovewwiiplanes.com

An invention that required far less brain power was Hawker’s solution to the problem of damaged propeller tips. The wooden propellers of the day were quite fragile and even taking off in long grass could shred the tips. Hawker simply doped fabric onto the tips to give some protection; a simple and effective solution that could be applied in the field. Later on, propeller tips and leading edges tended to be sheathed in thin sheet metal.

Above: Sopwith Pup propeller with fabric covered tips. www.woodenpropeller.com

Hawker returned to England in the autumn of 1915 for promotion and command of 24 Squadron. While on leave prior to taking up post, his dentist, William de Courcy Prideaux, showed him a patent clip for loading a revolver. Hawker suggested that a machine gun belt would be more up to date and Prideaux set about designing it in collaboration with Hawker. The outcome was the Prideaux Disintegrating Belt where the canvas belt of the Vickers gun was replaced by small interlinking metal clips simply held together by the rounds. As each round was withdrawn prior to being fed into the chamber, a clip was released and could be collected in a container or ejected overboard through a chute. Prideaux’s links were not the first of the type but were an improvement over earlier versions and were used by the RFC from early 1917 onwards. Similar links are still in use today.

Above: Prideaux Disintegrating Belt. www.cartridgecollectors.org

In the biography written by his brother it says that ‘Lanoe’s inventions were so numerous and diversified that it is not possible to describe them all, in fact many were taken into use without it being remembered that they originated in his fertile brain’. Many more inventions would have undoubtedly followed, but Lanoe Hawker was killed on 23 November 1916 after a lengthy dogfight with Manfred von Richthofen. The Germans buried him next to his downed aircraft near Bapaume, but his grave was lost and he is now commemorated on the Flying Services Memorial at Arras. A great pilot had died, but also in Tyrrel Hawker’s words: ‘Thus was lost an inventor, invaluable, irreplaceable’.

Article by Derek Bird, Chair North Scotland Branch

Bibliography: Hawker VC, RFC Ace: The Life of Major Lanoe Hawker VC, DSO, 1890-1916 by Tyrrel Hawker.