Le Cimetière Militaire de Soultzmatt, Alsace

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Le Cimetière Militaire de Soultzmatt, Alsace

We came across the cemetery by chance, driving through the Val de Pâtre along a peaceful road heavy with heat where the wine growing area gives way to the woodlands of the Vosges foothills, where a football field had been mown into the meadow and boys were laconically kicking a ball into the net. It was a carefully landscaped cemetery of crosses in a trefoil style which I hadn’t seen before, edged with deep beds of lavender, azure hydrangeas, neatly trimmed hedges and towering trees of mixed species.

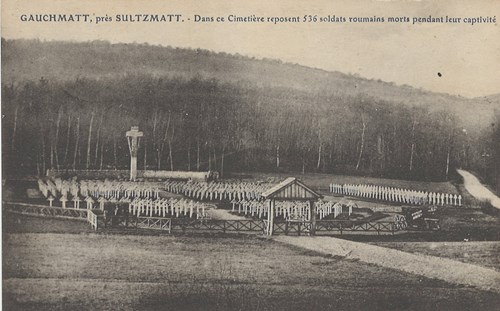

Here is the burial place of almost 700 Romanian prisoners of war, 562 in individual graves and 131 in two ossuaries. This is the largest Romanian military burial ground in France and the only one dedicated to prisoners. The authenticity of the location is overwhelming and shocking: this tranquil, solemn place is where the prisoners’ ordeal actually happened. The cemetery is differentiated from others by its polygonal plan with the sections and paths forming the shape of an Orthodox cross, its individual Latin crosses in white concrete and the elevated cross on a rough rock plinth adjacent to the flag of Romania. On each individual cross is a plaque showing the soldier's name (if known), his Romanian prisoner status, his number, the date of his death and a badge decorated with the coat of arms of the Romanian royal family.

On the plinth of the large elevated memorial cross are three marble plaques. The first says :

Les 687 prisonniers de guerre roumains qui dorment dans ce cimetière sont morts presque tous de janvier à juin 1917. Ils ont connu la faim, les privations et les tortures.

The second records the work of the Comité d’Alsace des Tombes Roumaines which was commissioned by the Romanian government to unite graves which were scattered across Alsace:

Il a acquis la preuve que tous ceux qu'elles abritent sont morts après d'indicibles souffrances.

In the third, Queen Marie of Romania expresses sympathy to the Romanian soldiers who died far from home. Nearby, a bronze statue has been erected in her memory as a tribute to her dedication in commemorating the dead.

Those plaques remind the visitor that this was a place of extreme suffering. Many Romanian soldiers taken prisoner by the Germans were deported to labour camps, especially in Alsace. The camp close to the pretty village of Soultzmatt was Kronprinzlager. Captives here were used as forced labour, constructing roads and shelters, felling trees, enduring intense cold, hunger, thirst and mistreatment. Local people put themselves at risk trying to smuggle nourishment for the prisoners. Conditions were especially difficult in the winter and spring of 1917. An ossuary contains the remains of 71 starving, suffering, skeletal prisoners who froze to death in an open barn in Steinbrunn-le-Haut on 27th January 1917 while their guards were out celebrating the Kaiser’s birthday. On exhumation, none of the prisoners could be identified. They were brought here in 1924.

Those who died here were placed before burial in the nearby 13th century chapel of the Val de Pâtre (also called Schaefertal). Initially, funerals took place on Sundays and each coffin was carefully lowered into its grave by four Romanian prisoners. As the severe winter of early 1917 progressed and deaths increased, funerals took place daily, even several times a day. There were also some German burials at this site.

When the war was over, the commune of Soultzmatt offered Romania the site which had comprised the wartime burial ground and the labour camp to create a cemetery. The landscape was cleared and bodies were brought from across Alsace to be buried in the newly created la cimetière du Val de Pâtre (or Gauchmatt). Chinese workers, accommodated by the local community, were employed on initial exhumations from the adjacent land and the scattered graves. On completion, the cemetery properly reflected Orthodox culture. Its wooden crosses were replaced with concrete crosses in 1930-31.

King Ferdinand and Queen Marie of Romania inaugurated the cemetery in 1924, the Queen placing flowers on each grave. Subsequently, she made an annual pilgrimage until 1939.

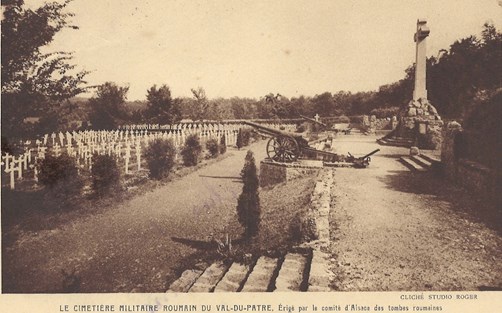

In 1920, the French Government donated four German artillery pieces to stand in the cemetery. My postcards show two German 10cm Konone placed next to the cross. Two more stood by the entrance. Unsurprisingly, they were repossessed in 1940.

From 1919 to 1939, the cemetery was maintained by le Comité d’Alsace des Tombes Roumaines, le Ministère des Pensions de Guerre and the municipal authority in Soultzmatt. It was abandoned in 1939, but care and commemoration resumed after the war. In the 1960s, the totalitarian Romanian government offered to contribute to the maintenance of the cemetery, but the offer was declined. That has now changed and Romania participates in its management.

Since 1999, the community of Soultzmatt has taken responsibility for caring for the cemetery to respect the ordeals of the dead. Nothing in the cemetery has been modified since 1939, making it architecturally faithful to its conception. As a highly symbolic site, regular commemorations take place on Jour des Héros, attracting Romanians from across Europe mingling with high ranking politicians, ambassadors, religious figures and local residents to commemorate those men who, in many cases, are buried where they died. It is also a place of personal pilgrimages and photographs suggest that it has been for most of a century.

A hundred years on, Soultzmatt and the Romanian government share the intention of remembering the link between Romania and the compassionate community which respected the prisoners in both life and death. In 2017, people gathered to observe the Centenaire du Martyre des Soldats Roumains and the Romanian royal family arranged for two trees to be planted, followed by an official visit.

The cemetery is now an historic monument and has been included in an application for UNESCO World Heritage Listing for memorial sites of the Great War.

Article and images contributed by Gwyneth M Roberts.

Resources:

- Cemetery plan page 3 http://www.paysages-et-sites-de-memoire.fr/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Fiche_HR07

- Resource : Les Roumains en France 1916-1918 https://www.slideshare.net/CristinaAndrei5/les-roumains-en-france-1916-1918

- Resource : Community leaflet – collections of extracts http://cdn3_4.reseaudespetitescommunes.fr/cities/743/documents/294os3opme7shi9.pdf