Queen Victoria’s Last VC

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Queen Victoria’s Last VC

26 June 2020 marks 120 years since Private Charles Ward delivered a message through a storm of bullets, an action that would later see him receive the Victoria Cross (VC). Charles was the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry’s only VC winner of the Boer War, and the last VC winner to receive the honour from Queen Victoria herself. Charles was welcomed back to his hometown of Hunslet, Leeds as a hero, but he later died in an asylum aged just 45, and his grave was unmarked and forgotten. The pension records, held by The Western Front Association, shed more light on his life after the army. What happened to Queen Victoria’s Last VC?

Charles Burley Ward was born in Hunslet, Leeds, in July 1876. His parents Annie and George were unmarried, so Charles was given his mother’s surname of Ward, with his father’s surname Burley as a middle name. There seems to have been some confusion around his date of birth. Charles listed his age as 19 years and 10 months old when he joined the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry (KOYLI) in April 1897, but he was actually just shy of his 21st birthday.

The 1st Battalion of the KOYLI were serving in Mullingar, Ireland, in August of 1897 and Charles joined them there. In May 1899, Charles was posted to the 2nd Battalion and left with a draft to join the battalion in South Africa. Charles, along with other KOYLI soldiers, were thrown into action when the Second Boer War broke out in October 1899. In June 1900, Charles was part of a group of soldiers who became surrounded by Boer fighters. Two officers were wounded, and all but six of the men had been killed or wounded. Private Ward volunteered to take a message asking for reinforcements, travelling from their exposed position to a signal station. At first, his offer was refused due to the certainty that he would be shot. Charles insisted, and managed not only to deliver the message, but to return under heavy fire and assure his commanding officer that the message had been delivered. During his return, he was shot in the arm. The official account in his medal citation states ‘but for this gallant action, the post would certainly have been captured.’ This action would earn him the Victoria Cross (VC).

Charles was invalided out of the army due to the wounds received during his VC action, and back in Britain he received treatment at Leeds Infirmary.

Above: The Victorian facade of the Leeds General Infirmary

By an unusual coincidence, Charles was treated by surgeon Berkeley Moynihan, whose own father Captain Andrew Moynihan was also a VC winner.

In December 1900, Charles was one of five men who were presented with their Victoria Cross by Queen Victoria herself at Windsor Castle. As Charles was the lowest ranking soldier of the five, he was last in line. Charles Ward became known as ‘Queen Victoria’s Last VC’ as the Queen died just a few weeks later.

When Charles returned to Hunslet, Leeds, in December 1900 he was given a hero’s welcome. Greeted by hundreds of people at the railway station, including the Lord Mayor, councillors, and his family, Charles seemed overwhelmed by the attention. After travelling through crowds, with accompanying music provided by the KOYLI band, Charles arrived at the Grove Hotel for a celebratory luncheon. The Leeds Mercury newspaper reported that Charles was asked to say a few words. He was interrupted by the crowd singing ‘For he’s a jolly good fellow’. He said “I am highly honoured by your flattering reception...” and with a ‘shy laugh’ said “I have only done my duty.” Charles was awarded a specially struck gold medal by Mr William Owen of Leeds and a cheque for £600, equivalent to over £60,000 today. The Leeds Mercury published a poem that had been specially written for Charles, titled ‘A Welcome from T’Leeds Loiner’, (loiner being a local name for someone from Leeds).

Remarkably, there is footage of Charles War which was shot for the filmmakers Mitchell and Kenyon. This footage shows Charles being interviewed - silently - by showman and regular Mitchell and Kenyon collaborator Ralph Pringle. The film makers clearly saw Ward's newfound celebrity as an opportunity to attract a large paying audience of proud locals.

A still taken from the Mitchell and Kenyon film of Charles Ward being interviewed by showman Ralph Pringle.

Click here to view the footage dating from 1901 (This link goes to an external website)

Charles ran a newsagents and tobacconist shop at 1 Church Street, Hunslet between 1902 and 1908.

Above, View of the Penny Hill area of Hunslet. Tramlines are visible in Church Street. Image courtesy of Peter Unwin via www.leodis.net

Later, he became a teacher of Physical Education at Bridgend Grammar School, Glamorgan, Wales, where he stayed until 1914.

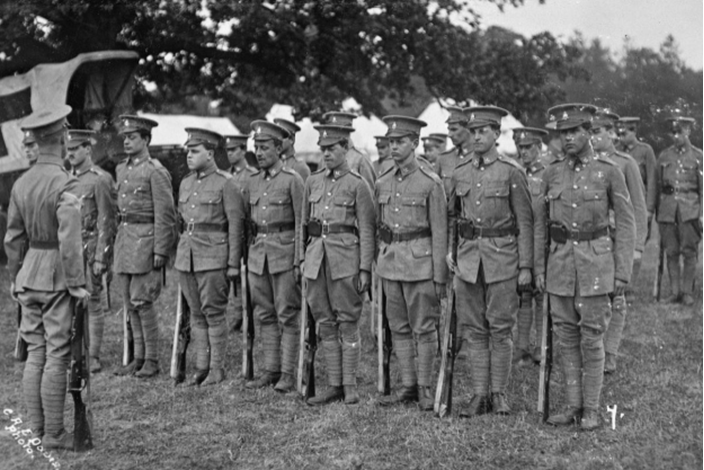

After the outbreak of the First World War, he joined the Duke of Wellington’s Regiment (West Riding) and served as a drill instructor, training new army recruits.

Above: A drill instructor at work. © IWM Q 90901

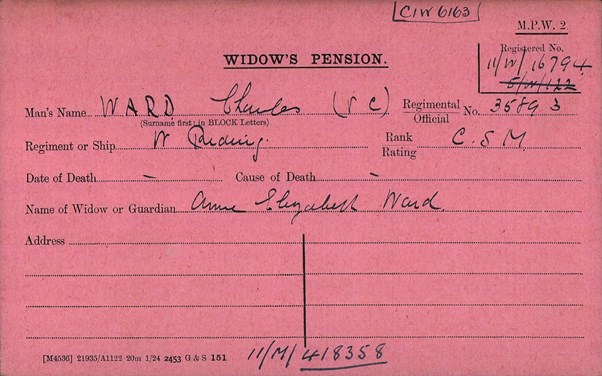

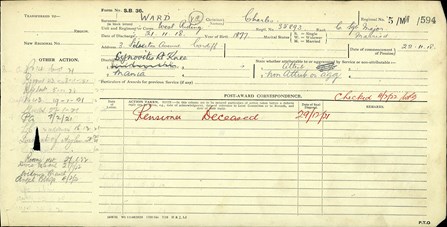

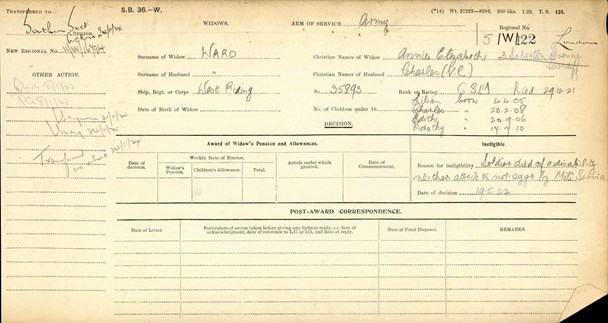

Some of the sources for his First World War experience are contradictory. It is clear he served with the 9th Battalion of The Duke of Wellington's Regiment (West Riding), as shown on his Medal Index Card, Medal Roll, Pension Record Card (see image below), Service Record and Silver War Badge Record.

His enlistment date is recorded as 10 September 1914. According to an article in the Yorkshire Evening Post from March 1919, Charles had been a speaker at recruitment events around Leeds, served as a drill instructor at training quarters including Pontefract and Ripon, and went to France in the last few months of the war. However, another contemporary article from The Western Mail in March 1915 states that he had been gazetted lieutenant the 3rd Battalion of the KOYLI and was serving in Bristol. His apparent commission is not corroborated by his other First World War records, which list him as a Warrant Officer Class 2, and it seems to have been an error on the part of The Western Mail. After the end of the war he returned to Wales, teaching at Barry County School.

Although he was considered a Yorkshire hero, Charles’s personal life was complex. Charles’s military pension record, accessed via The Western Front Association's records held on Fold3, states that when he was discharged from the army on 21 November 1918, he was considered to have two disabilities; synovitis of the right knee, and mania.

Above: The front and reverse of one of the pension ledgers for Charles Ward.

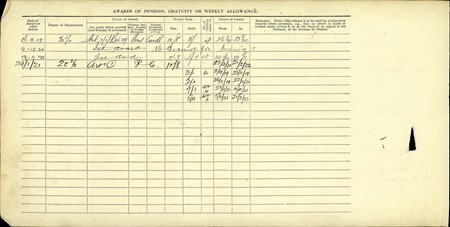

Below: The front of a further ledger record that has been located.

While the knee inflammation was considered attributable to military service, the mania was not. Charles married Emily Kaye in Hunslet in October 1904 and the couple had four children, Lillian, Edith, Charles Jr, and Dorothy between 1905 and 1910. Their marriage broke down in 1918, and in a tragic turn of events, Emily committed suicide in February of 1919. Charles remarried later that year, and he and his second wife, Annie, had one child together, Eric Burley Ward.

Charles Ward VC died on 30 December 1921 at Glamorgan County Asylum, Bridgend, Wales, aged just 45.

Above: The Glamorgan County Lunatic Asylum at Angelton, Bridgend

He was buried with full military honours in the churchyard of St Mary’s, Whitchurch, in January 1922. Both the KOYLI regiment and regimental association were represented at the funeral.

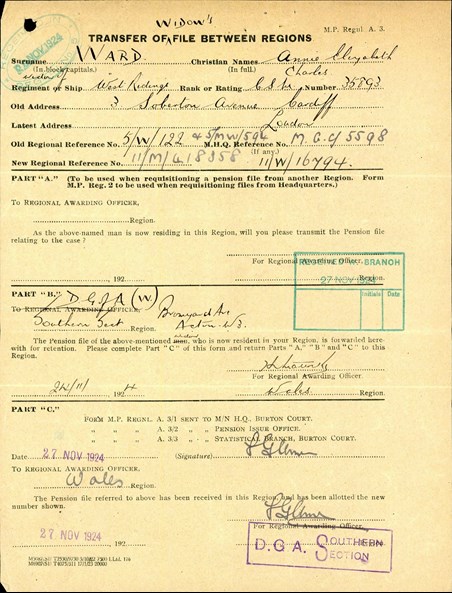

Among the pension records is a form (see image below) dated November 1924, sent between regions, detailing the situation regarding pension support for the Ward family. As Annie was Charles’s second wife, and they married after the end of his military service, she was not eligible for pension support.

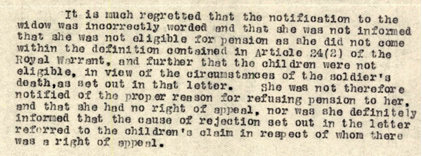

According to the a letter attached to the pension records (part of which is shown below), Annie had been notified that her pensions claim had been rejected, but the letter was ‘incorrectly worded’ and she was ‘not informed that she was not eligible for pension’. A card within the pension records states this decision was made on 19 May 1922, and the reason given was ‘Soldier died of a disability neither attributable nor aggravated by military service.’

Annie was the guardian of Charles’ children from his first marriage, and the letter goes on to state, ‘the children were not eligible, in view of the circumstances of the soldier’s death’. It goes on to confirm that Annie had no right to appeal, but the children did. It is unclear if they appealed, but the record detailing the weekly allowance for the children has no entries after 21 February 1922, two months after Charles’s death.

Charles’s family experienced financial difficulties after his death, and they moved away from Cardiff. In the years that followed, the family occasionally visited his grave, which was for some time marked with a small wooden cross. Over time, the grave was forgotten, but in 1986 a group of researchers identified its location. Working with the Ward family and the Royal British Legion, they arranged for a headstone to be placed on the grave. It was dedicated on 20 September 1986, eighty years to the week since the news of Private Ward’s VC win was published in the London Gazette.

Charles’s jacket, complete with bullet hole in the left arm, is part of the King’s Own Yorkshire Light Infantry Regimental Museum collection.

The jacket will be on display in the regimental museum within the new Danum Gallery, Library and Museum. It is understood that Charles’s medal set was sold to a private collector in the 1960s, but little else is known.

Article by Lynsey Slater, Assistant Museums Officer (Military History) Doncaster Museum

To read more about the Pension Records mentioned in this article, please click this link: FINDING HORACE

There is a vast array of articles about these records which can accessed here: PENSION RECORDS

Thank you to Charles’s grandson Mick Ward, West Yorkshire Archives volunteer Ronnie Walsh and Duke of Wellington’s Regiment (West Riding) Archivist Scott Flavin for additional information provided for this article.