Sentenced to Death. The Public Record Office Court Martial Files.

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Sentenced to Death. The Public Record Office Court Martial Files.

[This article originally appeared in Gun Fire No.31. It has been lightly edited for the purposes of publishing on the WFA's website. Illustrations have been added that did not appear in the original. All of these magazines are now available to WFA members via the Member Login. Joining the Western Front Association gives you access not only to the 59 editions of Gun Fire but also to all 110+ issues of the WFA's in house journal Stand To!]

Sentenced to Death. The Public Record Office Court Martial Files by A J Peacock

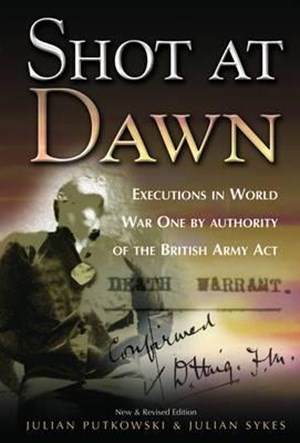

In recent years a great deal has been written about soldiers executed in the First World War. Gun Fire was early in the field with its story about Len Cavinder who took part in an execution. (1) A. Babington's disappointing bookFor the Sake of Example appeared in 1983 and it was followed by J. Putkowski and J. Sykes, Shot at Dawn. Not long after that C. Pugsley's, On the Fringe of Hell. New Zealanders and Military Discipline in the First World War was published and in Gun Fire No 27 the documents relating to the trial of Harry Farr were published. The latter are part of a number of files now available to the general public and here follows a series of notes about some of them. They were chosen more or less at random, none are very large, and all the characters involved, of course have already been named by Sykes and Putkowski.

PTE J. CUTHBERT

Pte J. Cuthbert of the 9th Cheshire Regiment was tried by court martial number 6078 along with Privates J. Dineen and W. Bate. He was shot at 4.45 am on 6 May 1916.(2) It was as clear a case as any in which a man was shot as an example to others. 'I regard this as a case where an example is necessary', the Commander of the First Army wrote, 'this man deliberately refused to obey an order owing to the element of danger attaching to it- I recommend the Sentence should be carried out in all Three Cases.' The Major General commanding the 19th Division answered a question thus '(a) I consider the state of discipline in the 9th(S) Bn. Cheshire Regiment to be good', but nevertheless consider 'that an example is necessary and strongly recommend that the Death Sentence be carried out in the case of Private Cuthbert.' He seemed totally unaware of the logical inconsistency of his reply. Discipline is good, but let us make an example, he reasoned. Perhaps he thought of the future -which was going to be very unfair on someone if that is the case.

Cuthbert and his co-accused were charged with disobedience, and the main evidence against them was given by a Sgt S. Carruthers. He told the court he was in charge of an eight man working party which he took up to the front line. He went to the company HQ in the line, and the men complained it was too light to carry out their task. Lt Kenyon, nevertheless told them to go over, and he went over himself followed by Carruthers and L Cpl Bailey. The rest stayed behind and Lt Walton was sent for. 'I heard Lt. Walton say "Come on I'll take you over to the parapet, follow me"' the sergeant said. All except Dineen, Bate and Cuthbert did so, and the wiring was duly completed. This was on the night of 14/15 April 1916.

L/Cpl Bailey also gave evidence for the prosecution. He was cross examined by Cuthbert who established that there had been much talk about the night being too light for a wiring party and Bailey agreed that 'When falling in at STRAND POST I had remarked that I thought it was too light and very risky.' Cuthbert also got him to agree that 'I said "come along, this is not the place to refuse. If there is any refusing to be done, do it to the officers in the firing line, and not to the N.C.O.s here."' A Pte Reach was another prosecution witness. In his evidence in chief he said (he was a member of the wiring party) that there was a general agreement 'that we would stand fast' and cross examined by Cuthbert he said that L Cpl Bailey said "'We will go up yonder, but we'll refuse to go over."'

Cuthbert, Bate and Dineen gave evidence on their own behalf, but did not take the oath, so were presumably not liable to cross examination. All said Carruthers said they should refuse to go over and that he told Kenyon it was too light to go out. Pte Devereux, another member of the wiring party, a defence witness, said that they had all decided to stand fast before they set off and that 'It was passed down from Sergt Carruthers [that] when we get near C Coy H.Q. for all of us to stand fast.' Pte Bailey, also for the defence, said that he had heard his namesake L Cpl Bailey suggest that they should all refuse to go out, while a L Cpl Yarwood said he had heard L Cpl Bailey say he thought 'it would be wrong to send them out.'

Sykes and Putkowski base their story about Cuthbert on Babmgton's For the Sake of Example and they comment that 'the instigator of' the decision to disobey 'was never identified.'

That may be strictly true, but from what has been written above it should be fairly clear that L Cpl Bailey and Sgt Carruthers were alleged to have been the instigators. A statement that 'the company quartermaster sergeant' appeared as a 'prosecution witness' is also not correct. L Cpl Bailey said that CQMS Fearnley had made the remarks that have been printed above, but Fearnley did not appear in the trial. Lastly it is said that the court did not consider the ability and reputation of Kenyon, the officer who was to lead the party (and who did not appear at the trial as he was wounded). Was the junior officer 'unfit to take the party out?' Sykes and Putkowski ask. Is this fair I wonder? It is perfectly clear that some NCOs and the men in the wiring party thought it was too light to go out, but Walton, the company commander thought it was safe. Kenyon had his orders and went out; the men refused to follow him. Thereafter Walton and Kenyon (it seems) went out with those that followed them and the work was successfully completed. This could be taken as an indication that they were right, but Kenyon was obeying orders, and there seems to be nothing in the court record that indicates (to me) that he was anything but competent. Lastly the record in Shot at Dawn should have recorded that the sentences on Bate and Dineen - '15 years' penal servitude' - were suspended.

Cuthbert's conduct sheet revealed nothing very serious, as Sykes and Putkowski contend, but it did have eight entries, including three for being insolent to NCOs. Dineen's record was worse, having a dozen, but Bate had only three recorded offences- all committed before embarkation. In mitigation Cuthbert again contended that it was too light to go out on the night of 14/15 April and Bate revealed that he had never been on a wiring party before. Dineen, however, had. 'I was out the night before wiring and a man was killed' he said, 'It shook me up. It was brighter still on the night in question. I had never been out before on wiring work until the 13th April. I had only had one hours lesson on wiring, and knew v. little about it.' Just before this, Lt Walton had told the court that the three just found guilty were 'good men. They are new to the Battn.' he said, 'having come over [in December 1915] with a draft from the King's Liverpool Regt.'

Cuthbert was shot as an example to others, yet came from a battalion in which discipline was said to 'be good'. As far as one can see, as the authors of Shot at Dawn said, it seems grossly unfair for Cuthbert to have been branded undesirable given the short period he had been in France and his conduct record. It is also abundantly clear that neither he, Bate or Dineen started off the protests about the wiring party. Those that did (Carruthers and Bailey) gave in when it came to an issue and went over. Cuthbert and the other two carried out the protest to its logical conclusion - and paid the price.

PTE A. TROUGHTON

Pte Troughton of the 1st Royal Welsh Fusiliers is not dealt with in Shot at Dawn, though he is mentioned. He was executed at 7 am on 22 April 1915. 'This is a bad case' Haig wrote on the 13th; 'I can see no extenuating circumstances in this case' wrote Rawlinson two days earlier. (3)

Troughton had gone out to France with the 7th Division on 7 October 1914 and his 'character ... from a fighting point of view' was said to have been 'good'. This would seem to be a very generous assessment, as Troughton could have seen very little action indeed. Atkinson's history of the 7th Division, for example, shows this. Nevertheless Troughton was slightly wounded, though there is confusion about when.

Troughton was prosecuted at his court martial by 2nd Lt J.B. Savage of his own regiment, and it was said that he deserted on either 18 or 19 October 1914 (days of very heavy fighting) from the area of Zonnebeke. He was finally arrested several months later in Boulogne (on 30 May 1915). In his defence, however, Troughton said that at Zonnebeke on or about 23 October he was slightly wounded on the wrist. Coming out of the trenches he had been told that his brother had been killed. 'This seemed to leave me quite silly. I wandered about FRANCE and I did not know where I was going.' From the trial record it seems reasonable to assume that Troughton gave evidence on oath, and so could have been cross examined. There is nothing to say he was. Savage might have questioned him on this, but if he did no record was made of it.

Had Troughton a bad record? It was impossible to say as 'His original Field Conduct Sheet has been lost - The accused states he had three years in 1/- R.W. Fus in November.'

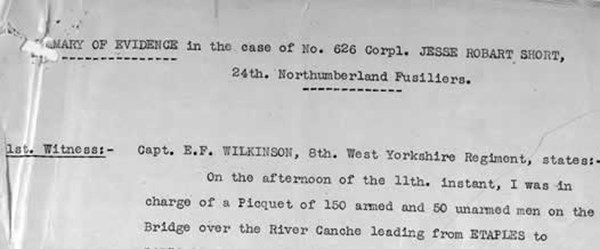

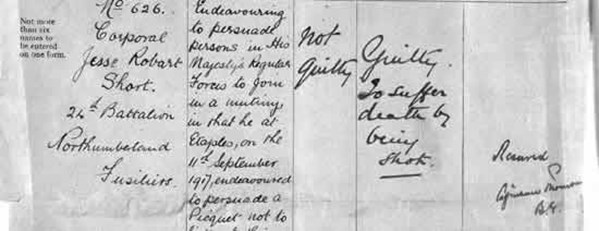

Above: documents from the FGCM of JR Short.

DRIVER JAMES SPENCER

James Spencer was a telephonist, and a member of the 65th Battery of the RFA who was tried and found guilty of deserting his post at Potijze on 12 June 1915. (4) He had joined the battery on 25 April, but maintained that he had served with the BEF since early in the war and had been wounded. Enquiries were made to ascertain whether this was so, but no records of him being injured or evacuated home were found. This was recorded in the notes about him penned by the Brigadier General Commanding the 5th Division Artillery. Sykes and Putkowski, following Babington, comment on these notes and say, surely correctly, that the Brigadier was wrong to state his opinion that Spencer deserted to spend some ill gotten gains on women and booze. (5) This was written after the trial, so could not have influenced those proceedings, but might have played a part in deciding Spencer's ultimate fate. It was clearly wrong to have written thus, but it seems fair to make two other points about the Brigadier. He did not conclude that 'Spencer was a deliberate skulker who should be shot' - he wrote about him in a way that can only be described as enthusiastic. 'During the three weeks preceding his absence', the Brigadier said, Spencer 'was employed as a telephonist. His work was satisfactory and he shared the dangers of the observing parties with ability and courage.' He had a completely clean conduct sheet.

Spencer's file is a very small one. The notes on his trial reveal that he was seen in the telephonists' dug-out at 5 pm on 12 June, but had gone an hour and a half later. The position was in a wood 'about 1700 yards from the German lines the place was frequently searched by shell fire by day and night, also at night there were a large number of stray bullets from the trenches.' What had Spencer to say about his crime ? 'The accused in his defence states that he remembers nothing from the afternoon of 11th June until the afternoon' when an MP found him saddling a horse in a barn in Vlamertinghe. The court was told Spencer had been given an excellent character 'as a telephonist and linesman since March 1915' by both his captain 'and Corpl. Callender with whom he has been working.'

Spencer really was a first offender, and there can have been few men who paid the ultimate penalty in WW1 who had such a good record and such glowing assessments from his superiors (spoiled it must be admitted by those comments about his motives for taking off).

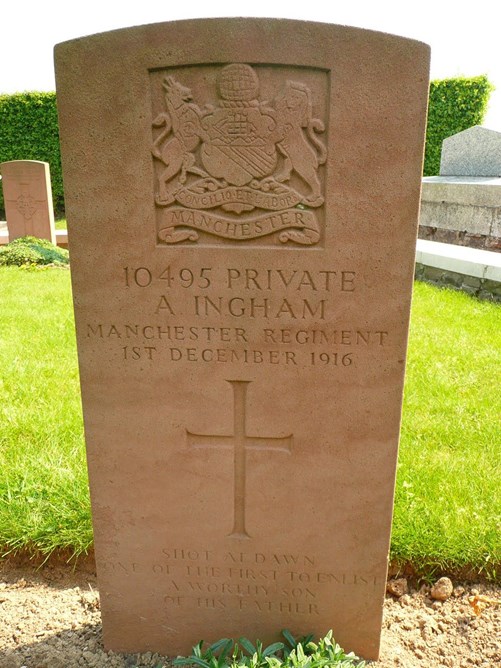

Above: The only headstone to reference a 'Shot at Dawn' fatality - Private Ingham of the Manchester Regt.

PTE J. TONGUE

Pte 11850 J. Tongue of the 1st King's Liverpool Regiment is another soldier who gets only a brief mention in Shot at Dawn. He was executed after a trial for desertion, the execution taking place between 6.30 and 7.45 am at Brailly on 8 January 1917. (6) 'The case is a bad one' wrote the commander of the Fifth Army. 'I am unable to concur in the view that a man who has been passed fit for General Service can be excused on the grounds of physical degeneracy', wrote Major General Walker, the Commander of the 2nd Division, 'The case is a bad one, and I recommend that the extreme penalty be carried out.'

What had happened in Tongue's case ? He had been in trenches at Montauban Wood and was missing when a roll call was made at 5 pm on 28 June 1916. He was missing until 29 November when he was arrested as he emerged from a disused building in Corbie. Tongue, who was a regular soldier and was 21 years of age, had served eleven months with the 1st King's Liverpool Regiment. In those eleven months he had behaved in an exemplary fashion and there were no entries whatsoever on his conduct sheet. During his trial he refused to cross examine prosecution witnesses, declined to give evidence and called no testimony as to character. It was revealed that he had taken part in a raid on Vimy Ridge on 6 June 1916 but had 'not taken part in any of the recent operations on the Somme.' On 1 January 1917 he had been before a medical board, (7) and it reported that it had examined 'the above named soldier and found that, with the exception of his having a highly nervous temperament, he is both mentally and physically sound.'

DRIVER J. BELL

Driver John Bell of the 57th Battery RFA was executed at 7.00 am on 25 April 1915 'at the 57th Battery Waggon Lines' for the crime of desertion. (8) He is another man who is mentioned, but not dealt with at length in Shot at Dawn. The file on him and his co-accused is larger than usual. Eleven prosecution witnesses appeared against Bell, who faced two charges (the finding of guilty on the second was quashed 'on account of inadmissible evidence').

What had Bell done ? On 20 October 1914 he and number 69606 Driver Wilkinson were detailed to march with the dismounted parties in the rear of baggage wagons making their way to Poperinghe. At the end of the journey they were missing, and were eventually arrested two months later by a French gendarme about two miles from Boulogne (on 18 December). The two absentees made three attempts to escape before they were taken to the Stragglers' room at Boulogne, Bell was handed over to Sgt C.A. Mudge of the 1st East Surreys 'as a straggler' on Christmas Eve, but was not put under close arrest, and on Boxing Day he took off again, to be rearrested two days later. He escaped at least once - and maybe twice-more.

At his court martial Bell, unlike many of those on trial for their life, spoke on his own behalf.

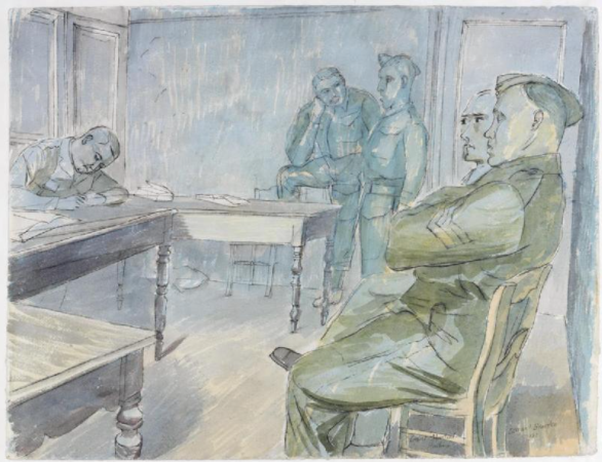

The above depicts a Second Word War Court-martial, at Halluin (1940), IWM Art.IWM ART LD 179

According to his story he fell out without permission on the march to Poperinghe, then tried to rejoin his comrades but found they had gone. He and Wilkinson spent the night in a French billet and reported the following day to the HQ of the 1st Division. From there they went to a Belgian HQ and looked elsewhere for their unit. The two deserters then got on a train which was heading for Paris. They got off and decided to walk to Boulogne. They got as far as La Cappelle where they were arrested on 15 December- not the 18th as had been alleged. They did not resist, Bell was at pains to point out. 'We would not have let one man arrest us, if we had wished to get away' he said. What about his escape at Christmas time? Security must have been extraordinarily lax if there was a grain of truth in what he said. He went out of his place of arrest with a corporal from the North Lancashire Regiment, Bell said, got lost and was arrested, then put into a cell with German prisoners and a spy. He took off again. 'I was with the Leicestershire Regt. for 7 weeks & if I had wanted to run away I could easily have done so' Bell said, 'I went there about Feby 1915.'

Wilkinson was tried with Bell and he told a similar story about his exploits when he was with Bell, but then they were separated. While he was awaiting trial he took part in an incident which may well have saved him from the same fate as Bell. On 6 April 1915 Wilkinson was in a guard room when a serious fire broke out nearby. Clearly all the personnel there rushed to help and Wilkinson had an opportunity to escape. He did not take it. A Cpl Lewis wrote a letter saying he thought Wilkinson had gone, but 'afterwards discovered that he was working as hard as anyone to extinguish the fire which occurred in a portion of a barn used for office purposes'. A letter from a Sgt W. Andrews said Wilkinson 'greatly assisted in extinguishing a fire at La TOMOE WILLOTT' and General Willocks, reading all this, came to the conclusion that 'Driver Wilkinson might well be mercifully treated as at least he has since deserting done something to show he may alter his ways.' The court also thought that 'the accused was greatly influenced by Dr. Bell' and Haig duly commuted his sentence from death to five years penal servitude.

PTE J. HARRIS

'This is a bad case & the man deserves no mercy' Lord Cavan wrote about Pte J. Harris of the 10th Lancashire Fusiliers, 'I recommend that the sentence [of death] be carried out.' Cavan was then the Commander of the 14th Corps. Others, of course, agreed and among them was the commander of the 52nd Brigade. He gave the reasons why he thought Harris should be shot. They were that: Harris had already been sentenced to death for desertion, a sentence which had been commuted to five years penal servitude suspended; he had already had a sentence of two years hard labour for absenting himself that had been suspended; the act for which he had just been tried was deliberate; and he was a bad soldier. Discipline in the 10th Lancashires was said to be good, but despite that 'In the interests of discipline, I recommend that the sentence be carried out' the commander wrote, adding that in his opinion Harris wilfully misconducted himself in order to be sentenced to imprisonment and thereby avoid service in the trenches. (9)

Harris's conduct sheet reveals that in addition to the two years hard labour suspended, mentioned above, and the sentence of death for desertion (on 1 October 1916), he had received 14 days Field Punishment No 1 for losing his rifle and seven days FP2 for not complying with orders. The brigade commander's opinion that he was a bad soldier seems indisputable. Harris was shot at 6.50 am on 3 February 1917 for offences committed just a month earlier. He was alleged to have absented himself on 2 January and given himself up ten days later to Sgt Rogers of the 11th Rifle Brigade near Corbie.

Sykes and Putkowski devote only a few lines to Jack Harris, basing their remarks on him on the PRO document WO 75 2490, and saying that 'It is not perhaps surprising that ... the Commander-in-Chief decided to implement the extreme penalty.' Harris's file is very slight and contains brief notes about the evidence given by three prosecution witnesses: Rogers, who gave evidence of the offender's arrest; a Cpl Gutteridge who said he had heard Harris refuse to go up to the front line; and a CSM. The latter said Harris's company had been ordered to go to Guillemont on fatigues on 1 January, but Harris had refused to go. When the roll was called on 2 January he was absent. Harris cross-examined the CSM and elicited the fact that the NCO had been told about his two years suspended sentence. (He was also on that five year suspended sentence.) In his defence statement Harris really does seem to have made the prosecution's case. 'I left my Regiment', he said, because 'I had been given' two years hard labour, 'It being understood men doing hard labour went away from that Battalion & it seemed to me that no one wanted to give me a chance - as I had heard many remarks about me.'

RIFLEMAN F. HARDING

Frederick Harding, No 11528 of the 1st King's Royal Rifle Corps was executed at 4.28 am on 29 June 1916 at Cambia in L'Abbe for absenting himself from the front line at Souchez on 4 May 1916, and then repeating the offence. He was apprehended at Hesdin on 19 May not wearing a cap badge or numerals, carrying no equipment and wearing riding breeches and a service jacket with black buttons. He was locked up at Fresnicourt but escaped from there on the 21st. He was caught at Bethune six days later. Harding was given a dreadful character in submissions for his court martial. His conduct in action was said to have been 'bad', his conduct from a fighting point of view was 'fair', and his previous conduct was 'bad'. He had enlisted for the usual 12 years service on 8 April 1914 and was wounded 'About 2nd' November. It seems that he spent some six months in hospital and rejoined the 1st KRRC in November 1915. Harding's file (10) is large by comparison with those of many of the men executed between 1914 and 1918 and contained in it are extracts from an AFB 122 form which made the point that he had, indeed, been a poor soldier.

Offence Last 12 months Since enlistment

Misc 11 11

Drunkenness 1 1

Absence 3 4

Insubordination 1 1

Disobedience 3 3

In his defence submissions Harding's head wound of 1914 was mentioned and it was also said that since the age often he had suffered from 'wandering mania'. The court was adjourned for the accused to be medically examined and the report on him said that he was indeed mentally 'dull'. Enquiries were made about his wandering and before the court were a number of documents from the police. One of these was a message from the Metropolitan force which said 'RIFLEMAN HARDING TENDENCY TO WANDER WEAK INTELLECT.' A letter said that he had been taken to a police station for wandering in 1913, but another from an Inspector Flanders said that in March 1912 Harding had been charged with wandering and begging and that he had been in St Giles Mission Home, Drury Lane, until December 1913. Another note said he had been convicted of begging in 1911.

Harding was a pathetic character and Sykes and Putkowski are surely right when they say he should never have been a soldier and that he 'fell victim to ... the army's inadequate enlistment screening, as well as his own personal failings.' Henry Wilson did not think he should be shot, but the C in C did. Perhaps he was finally influenced by the fact that one of those offences absenting himself from duty had been committed as recently as 9 March 1916. For this Harding had appeared before a Field General Court Martial which had awarded him 84 days Field Punishment Number One on 28 March. it is one which reveals that a medical report on the accused had been called for. The Lt General Commanding XV Corps said that Hart said he had been buried by a shell and 'his nerves ruined', but that the medical report on him was 'such as to afford no excuse for his conduct'. He recommended that the death sentence should be carried out. A Capt W. Brown, a neurologist, reported that he had observed Hart for a period of four days, but had 'found no evidence of feeblemindedness or other mental defect.' Two statements (from a Lance Cpl Ratcliffe and a Pte Purcell) confirmed that Hart had been buried by an explosion at Cambrin in March 1916. This was two months after he had arrived in France. Hart had enlisted on 22 October 1913 and had previously worked in an iron foundry in Ipswich. On 17 November 1916, ten months after his arrival on the Western Front and eight months after the incident at Cambrin, he had been given a sentence of five years' penal servitude, suspended, for desertion. It was this which sealed his fate-that and the need for yet another example. A pencilled note on a comment from the commander of the 98th Infantry Brigade said 'I concur. This man has escaped the extreme penalty before owing to insufficient evidence.' What the writer concurred with was a statement which said 'this man is one of three who have been setting a bad example to the remainder of the battalion by absenting themselves from tours of duty in the trenches: I consider an example should be made.' Hart's final crime had been committed at Petit Bois on 14 December 1916 when he left the trenches at 2.15 pm. He was caught two days later at Bray (where he was tried 12 days later).

PTE B. HART No 1763

Pte Benjamin Hart of the 1/4th Suffolk Regiment was one of those soldiers who was shot (at Suzanne on 6 February 1917) and whose story had been told in print long before the details of his trial were released (or before the appearance of Shot at Dawn) though, of course, his name had not been revealed. Hart's court martial file is tiny, (11) but it is one which reveals that a medical report on the accused had been called for. The Lt General Commanding XV Corps said that Hart said he had been buried by a shell and 'his nerves ruined', but that the medical report on him was 'such as to afford no excuse for his conduct'. He recommended that the death sentence should be carried out. A Capt W. Brown, a neurologist, reported that he had observed Hart for a period of four days, but had 'found no evidence of feeblemindedness or other mental defect.' Two statements (from a Lance Cpl Ratcliffe and a Pte Purcell) confirmed that Hart had been buried by an explosion at Cambrin in March 1916. This was two months after he had arrived in France.

Hart had enlisted on 22 October 1913 and had previously worked in an iron foundry in Ipswich. On 17 November 1916, ten months after his arrival on the Western Front and eight months after the incident at Cambrin, he had been given a sentence of five years' penal servitude, suspended, for desertion. It was this which sealed his fate-that and the need for yet another example. A pencilled note on a comment from the commander of the 98th Infantry Brigade said 'I concur. This man has escaped the extreme penalty before owing to insufficient evidence.' What the writer concurred with was a statement which said 'this man is one of three who have been setting a bad example to the remainder of the battalion by absenting themselves from tours of duty in the trenches: I consider an example should be made.'

Hart's final crime had been committed at Petit Bois on 14 December 1916 when he left the trenches a t2.15 pm. He was caught two days later at Bray (where he was tried 12 days later).

PTE OLIVER HODGETIS

A routine order from the 8th Division dated 5 June 1915 contained some details about 8622 Pte O. Hodgetts of the 1st Worcestershire Regiment who was shot at Pont Logy for cowardice the previous day. Hodgetts had been warned with his colleagues that they would be going into action on 9 May (the date of the attack on Festubert) but went missing. He gave himself up in Laventie on 13 May (two days after his battalion suffered numerous casualties). What did he say happened? He said that as his unit moved off he fell and damaged his ankle and stayed where he fell. In the evening he went to the rear looking for a doctor. 'There was a lot of shell fire going on', he said, 'and I was quite dazed and was not aware of what I was doing. Two or three days afterwards I reported myself to the Scottish Rifles in Billets.'

Also on the routine orders of 5 June, along with the announcement of Hodgetts's death, was another note - 'He has been convicted before of "Desertion" and also of "leaving the firing line without permission."' In his court martial file are extracts from his conduct sheet. (The first dates are the dates of the offence.)

1. 12 January. 'Absent from marching to the trenches', an offence for which he received 72 days Field Punishment Number One on 16 January.

2. 30 January. For 'Falling out without permission' he was sentenced to lose 14 days pay on 3 February.

3. 11 February. For 'Not complying with an order' Hodgetts lost seven days pay (on 15 February).

4. 17 February. On 1 March 1915 Hodgetts received 90 days Field Punishment One for 'deserting His Majesty's Service' while 'on Active Service'.

5. 12 March. For 'leaving the firing line without permission when on active service Hodgetts received 28 days Field Punishment Number One on the last day of March.

According to the commanding officer of his battalion Hodgetts had been with the BEF for five months when he took off from Rue Petillon, and if this is true, as it surely is, it means that he was offending from the very start of his active service. 'This is the 3rd attempt that he has made to get away from his unit', the commander said and, 'During the action at NEUVE CHAPELLE ... in the heat of the fight' he deserted, but because of the death of witnesses to his cowardice he was not tried by a Field General Court Martial'. For 'the sake of an example and of acting as a deterrent in the future, I would respectfully submit that it would be a pity if a lenient view' was taken of 'this military crime' the Worcesters' colonel concluded. Haig's view was that 'this is a very bad case of deliberate intention to desert so as to save himself from the enemy's bullets - The man is worthless as a fighting soldier.'

A.J. Peacock

- Gun Fire No 2 (nd)

- Public Record Office reference WO 71464. He is dealt with in J. Putkowski and J. Sykes, Shot at Dawn (1992 edit) pp 76-78

- WO 71413

- WO 71433

- The Brigadier drew attention to the fact that Spencer when caught had in his possession a large sum of money which, the officer thought, 'he had obtained from one ruined house in YPRES ... and that he absented himself to spend it on "women and drink."'

- WO 71536

- By order of the GOC of the 2nd Division

- WO 71412

- WO 71542

- WO 71479

- WO 71537