Some instances of the award of the Albert Medal in the First World War

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Some instances of the award of the Albert Medal in the First World War

During the Great War the Albert Medal was awarded to fewer than one hundred servicemen. Less than one third of these awards were made posthumously, so finding examples of men awarded this medal in CWGC cemeteries is difficult.

Below are two citations for acts of supreme bravery during the First World War. It will be noticed that the circumstances of both incidents are quite similar. The first instance was on the Somme in 1916:

For most conspicuous bravery. While in a concentration trench and opening a box of bombs for distribution prior to an attack, the box slipped down into the trench, which was crowded with men, and two of the safety pins fell out. Private McFadzean, instantly realising the danger to his comrades, with heroic courage threw himself on the top of the Bombs. The bombs exploded blowing him to pieces, but only one other man was injured. He well knew his danger, being himself a bomber, but without a moment's hesitation he gave his life for his comrades.

The second was in the Ypres salient in the depths of winter, on the penultimate day of 1917.

Lt. Thorner was examining some Mills hand grenades in a small concrete dug-out in France [sic - it was Belgium] prior to taking them up to his machine-gun position during an expected enemy raid. One of the grenades began to fizz when taken out of the box. There were twelve men in the dug-out at the moment and there was no possible means of disposing of the bomb. Realizing what had happened Lt. Thorner shouted to his men to clear out whilst he himself held the bomb in his hand close to his body until it exploded and killed him. By this magnificent act of courage Lt. Thorner deliberately sacrificed his own life for others. Of the twelve men who were in the dug-out all but two escaped without injury - they were slightly wounded.

The curious matter here is that, as is well known, McFadzean was awarded the Victoria Cross, but in the little known incident in the Ypres salient, Thorner was 'only' awarded the Albert Medal.

Above: Lt Harry Thorner. Harry was born in Shadwell, one of ten children of William and Marion Thorner (nee Land) in March 1887.

Above - The Victoria Cross.

Above - two versions of the Albert Medal - The version on the left being the one for saving life at sea. The version on the right for saving life on land. Eventually there were two classes (first and second) but titles of the medals changed in 1917, the gold "Albert Medal, first class" becoming the "Albert Medal in gold" and the bronze "Albert Medal, second class" being known as just the "Albert Medal".[1]

When comparing the incidents for McFadzean to Thorner, it is difficult to understand why a VC was not awarded to Lt Thorner. Both incidents seem to have been 'in the presence of the enemy' which is a pre-requisite for the award of a Victoria Cross, (unless the slightly ambiguous citation for Thorner 'during an expected enemy raid' suggests that the raid did not take place). So the only explanation may be that officers were on hand to witness McFadzean's act, but no officers (other than Thorner himself) were present at the second incident.

The Albert Medal and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission

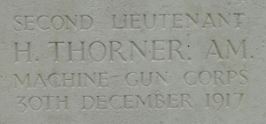

Because the CWGC headstones of the men who were killed after being awarded an Albert Medal (or who were awarded the medal posthumously like Lt Thorner) do not have any emblem to mark the award of an Albert Medal, these headstones are very difficult to spot in CWGC cemeteries.

Above: Thorner's headstone at The Huts Cemetery near Dikkebus.

Above: A close-up of the detail on Thorner's headstone. The 'AM' after his name being the only indication of the award of the Albert Medal

Although the headstones are difficult to spot, the CWGC often provide the citation for the acts of bravery that resulted in the award of the Albert Medal. For instance, Thorner's citation is recorded by the CWGC on their database, however this is not consistently undertaken by the commission.

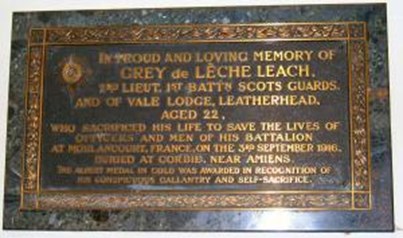

One example of a citation not being recorded by the CWGC is that of 2/Lt Grey de Lèche Leach (photo below).

On 3 September 1916 2/Lt Leach of the 1st Battalion Scots Guards was mortally wounded again in a grenade incident. He was awarded an Albert Medal "in recognition of the conspicuous gallantry and self-sacrifice"

This is the citation for the award of the Albert Medal:

Lieutenant Leach was examining bombs in a building in France on 3rd September, 1916. Two non-commissioned officers were also at work in the building, when the fuse of one of the bombs ignited. Shouting a warning, he made for the door, carrying the bomb pressed close to his body, but on reaching the door he found other men outside, so that he could not throw the bomb away without exposing others to grave danger. He continued, therefore, to press the bomb to his body until it exploded, mortally wounding him. Lieutenant Leach might easily have saved his life by throwing the bomb away or dropping it on the ground and seeking shelter, says the official announcement, but either course would have endangered the lives of those in or around the building. He sacrificed his own life to save the lives of others.

Leach is buried at Corbie Communal Cemetery extension. The inscription on his headstone is most appropriate:

"GREATER LOVE HATH NO MAN THAN THIS THAT A MAN LAY DOWN HIS LIFE FOR HIS FRIENDS"

Above: A memorial tablet to 2/Lt Leach is in the north aisle of St Mary & St Nicholas Parish Church, Leatherhead

As mentioned above, despite the award of the Albert Medal being noted on the CWGC database, unfortunately the CWGC do not provide the text of the citation. This is the case, for some reason, for exactly half of those men who have been awarded the Albert Medal and were killed during or shortly after the First World War (and who are therefore commemorated by the CWGC).

The detailing of the citation for the Albert Medal on the CWGC database falls into three categories

- Those who were killed in the incident for which they were (posthumously) awarded the AM (nine men seem not to have their citations recorded by the CWGC). This would seem to be a definite omission.

- Those who were killed subsequent to the award of the AM and the award was earned for a 'military' incident during the course of the war. In this instance six men seem not to have the citation on the CWGC database - this can be classed as a 'possible omission'.

- Those who were killed subsequent to the award of the AM but the award was granted prior to the war and/or for a non-military incident . Seven men fall into this category. It is possible that the award of the (pre-war) act is deemed by the CWGC as not being relevant and the citation is deliberately excluded from the CWGC entry in these cases.

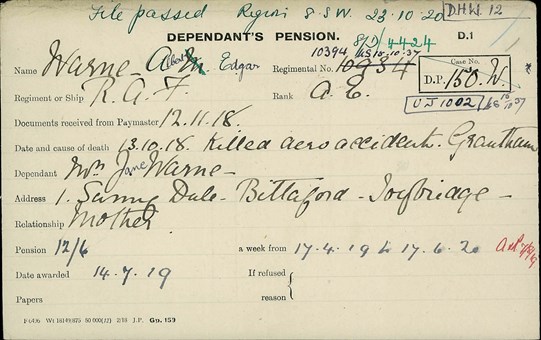

The inconsistency around the awards is shown in the case of Chief Mechanic Albert Warne who was killed subsequent to the award of his Albert Medal, but the CWGC detail the citation for his award on their database:

‘On the 26th January [1918], while flying in England, a pilot when attempting to land lost control of his machine, which crashed to the ground from a height of about 150 feet, and burst into flames. Flight Sergeants Warne and Cannon went to the rescue of the pilot at great personal risk, as one tank of petrol blew up and another was on fire; moreover, the machine was equipped with a belt of live cartridges, which they dragged out of the flames. They managed to extricate the pilot, who was strapped to the burning plane, but he died shortly afterwards from his injuries and burns.’

Above: The Albert Medal and 'dead man's penny' of Albert Warne.

The original recommendation given by Captain H.S. Lees-Smith, Commanding ‘B’ Flight, 50 Training Squadron, Royal Flying Corps adds further detail:

‘Fatal Aeroplane Accident to 2/Lt. Machpherson [sic]. I have the honour to report and bring to your notice the action of F/Sgt. Cannon H. No. 50 T. S. and F/Sergt. Warne, A. R. S. in the clearing of the above named Pilot from the wreckage of the Aeroplane. Lieut. F. M. Paul and myself were the first Officers to arrive at the crash. The machine was in full blaze with the Officer caught in the wreckage below the seat; both N.C.O.s were under the burning plane dragging the Officer out who was still alive although on fire. One petrol tank blew off immediately after our arrival and the emergency tank was on fire at the same time. In addition the machine was equipped with a belt of live cartridges which they dragged out of the flames, F/Sgt. Cannon receiving burns to his hands in doing so. This rescue was carried out at great personal risk and is in my opinion worthy of recognition.’

The pilot (who - as noted above - died of his injuries) 2/Lt. McPherson was - curiously - despite being killed in Lincolnshire, exhumed and is now buried in Toronto, Canada.

Warne was subsequently posted as a Chief Mechanic to 39 Training Depot Station, and was ‘killed as result of being struck by propeller’ on 13 October 1918. He is buried in St. Peter’s, Ugborough, Devon.

Above - the Pension Record Card for Albert Warne, detailing 'Grantham' as being where he met his death in an accident less than a month before the end of the war.

These pension cards can be seen by all members of The Western Front Association by logging on to the WFA web site. Details of these records are explained in a number of articles on the WFA web site.

Grenade Incidents and Accidents

The number of grenade-related incidents that resulted in the award of the Albert Medal is significant.

Above: Portuguese troops at bomb throwing practice (National Library of Scotland)

As can be seen from the citation below, 2/Lt Hankey seems to have had to make a habit out of saving men from grenade accidents - having saved the lives of others three times within a matter of a few weeks!

On the 15th October, 1915, Second Lieutenant Hankey was in charge of a party under instruction in throwing live grenades. A man who was throwing a grenade- with a patent Noble lighter became nervous when the-lighter went off and dropped the grenade at his feet. Second Lieutenant Hankey at once picked up the grenade and threw it out of the trench. There were four men in this section of the trench.

On the 4th December, 1915, while Second Lieutenant Hankey was in charge of a party under instruction in throwing live grenades, a man pulled the pin from a grenade and threw the grenade straight into the parapet. Second Lieutenant Hankey at once picked up the grenade and threw it over the parapet. There were four men in the throwing pit at the time.

On the 6th December, 1915, Second Lieutenant Hankey was in charge of a party under instruction in throwing live grenades from a catapult. A live grenade was placed in the pocket of the catapult, the fuse was lighted, and the lever released. The grenade for some reason was not thrown by the catapult, and fell out of the pocket on to the ground. Second Lieutenant Hankey, who was standing on the other side of the catapult to that on which the grenade lay, rushed at the grenade, seized it, and threw it away. The fuse was a short five second fuse, and the grenade exploded on hitting the ground 15 yards away. There were eight men near the catapult at the time, and ten others not far away.

Above: Thomas Barnard Hankey (1889-1969)

Another example of one of the incidents that the medal was awarded after a grenade accident is that for Acting 2nd Corporal Walter Beard of the Royal Engineers. The London Gazette dated 10 December 1918 states:

'On the 16th August, 1918, Lance-Corporal Beard was instructing recruits in throwing live bombs, when one of the men under instruction, as he was about to throw the bomb, dropped it in the trench. Beard at once ran out from cover, picked up the bomb, and threw it over the parapet, thereby undoubtedly saving the recruit from death or serious injury. The bomb exploded in the air before reaching the ground. In almost exactly similar circumstances Beard repeated this gallant action on the 23rd August thereby again saving the life of a man who had dropped a bomb in the trench.'

Above: The medal group belonging to Walter Beard - these are valued at £8500 according to 'British Medals' (R & A Alcock Ltd)

What price bravery?

The value placed of these medals can vary a great deal - in 2014 one was sold for £18000, this being one awarded to Lance Corporal James Collins. This award was again for the act of saving others from a grenade blast - although on this occasion it was not an accident ! Collins had been escorting a 'lunatic' soldier through the trenches when the soldier escaped. The London Gazette states:

"Collins ran after him, and when he got near him the man threatened to throw a bomb at him. Collins closed with the man, who then withdrew the pin from the bomb and let it fall in the trench. In an endeavour to save the patient and two other soldiers who were near, Collins put his foot upon the bomb, which exploded, killing the lunatic and injuring Collins severely. Fortunately the two soldiers were not hurt. Collins, who could easily have got out of the way, ran the gravest risk of losing his life in order to save others."

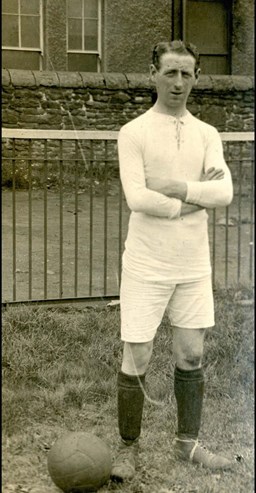

Despite suffering devastating injuries and being told he would have to have his leg amputated Collins astonished doctors by going on to play professional football for Swansea Town (the football club is now known as Swansea City).

Above: L/Cpl Collins outside Buckingham Palace with his mother, after receiving the Albert Medal

Above: Collins when he was a Swansea Town footballer

Yet another grenade accident is related here, which cost a sailor (of the Royal Naval Division) his life.

An extract from the London Gazette dated the 1st January 1918, records the following "The King has been graciously pleased to award the Decoration of the Albert Medal in recognition of the gallantry of Petty Officer Alfred Place, late of the Royal Navy." The circumstances are as follows:

"At Blandford, on the 16th June, 1916, during grenade practice, a live bomb thrown by one of the men under instruction fell back into the trench. Petty Officer Place rushed forward, pulled back two men who were in front of him and attempted to reach the grenade with the intention of throwing it over the parapet. Unfortunately, the bomb exploded before he could reach it and inflicted fatal injuries. By his coolness and self-sacrifice Petty Officer Place probably saved the lives of three other men."

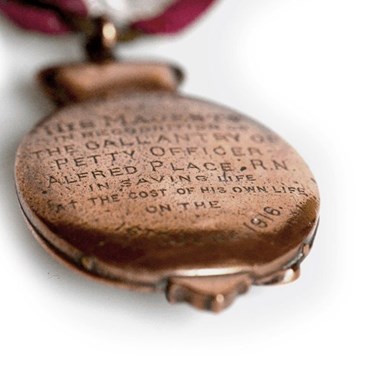

Above: The detail on the reverse of Alfred's medal

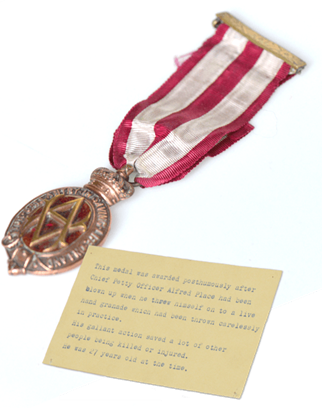

Above: Alfred Place

Above: Alfred Place's Albert Medal

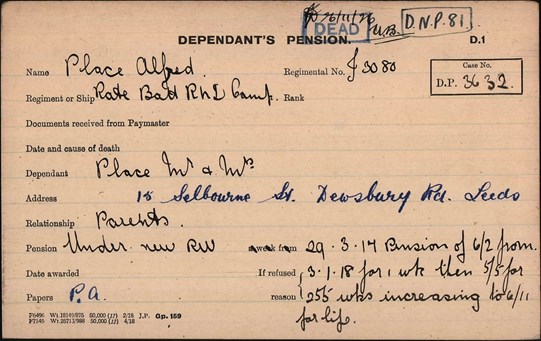

Above: The Pension Record card showing his parents details - the address (15 Selbourne Street, Dewsbury Road, Leeds) and pension awarded.

Above: The headstone of Alfred Place - which is located at Leeds (Hunslet Old) Cemetery does not note the award of the Albert Medal.

An ammunition dump prevented from going up !

Perhaps the most well documented case of the award of the Albert Medal is for an incident in the Ypres salient - this time not involving a hand grenade accident. The story is well told in the following citation

The London Gazette", No. 30,876, dated Friday, 30th Aug., 1918, of the acts for which the Albert Medal was awarded to

C.S.M. A. H. Furlonger, D.C.M.,

Spr. J. C. Farren and

Spr. G. E. Johnson,

In Flanders, on the 30th April, 1918, a train of ammunition had been placed at an ammunition refilling point, and after the engine had been detached, and was being run off the train, the second truck suddenly burst into flames. [Company Sgt Major A.H.] Furlonger immediately ordered [L/Cpl. J. E.] Bigland, the driver, to move the engine back on to the train for the purpose of pulling away the two trucks nearest the engine.

Bigland did so without hesitation, and the engine was coupled up by Furlonger, assisted by [Spr J.C.] Farren, while the burning truck was uncoupled from the remainder of the train by [Spr. J. H.] Woodman. The two trucks were then drawn away clear of the ammunition dump, it being the intention to uncouple the burning wagon from the engine and the first wagon and so isolate it, with the object of localising the fire as far as possible.

The uncoupling was about to be done when the ammunition exploded, completely wrecking the engine and both trucks, killing Furlonger, Farren and [Spr G.E.] Johnson (a member of the train crew), and seriously wounding Bigland.

Had it not been for the prompt and courageous action of these men, whereby three of them lost their lives and one was seriously injured, there is not the slightest doubt that the whole dump would have been destroyed and many lives lost.

Above: An example of a light railway engine (IWM HU 110848). It is not known what type of engine was being operated in the incident related above.

Above: Buried side by side at Haringhe (Bandaghem) Military Cemetery are the three Royal Engineers, who were all killed on 30 April 1918. Left to right: Spr Joseph Farren; Spr George Johnson; C.S.M. Alfred Furlonger, D.C.M.,

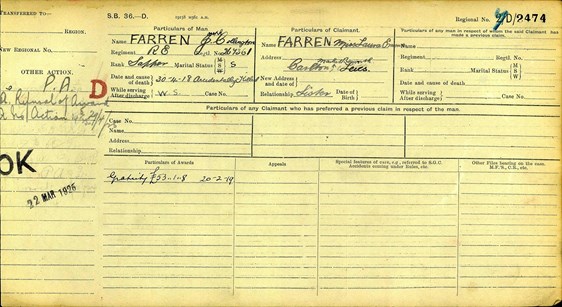

Above: The Pension Ledger for Farren

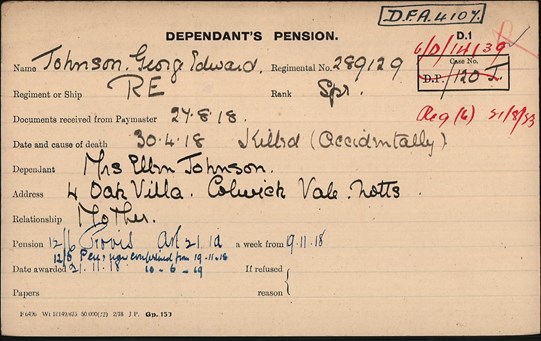

Above: The Pension Card for Johnson

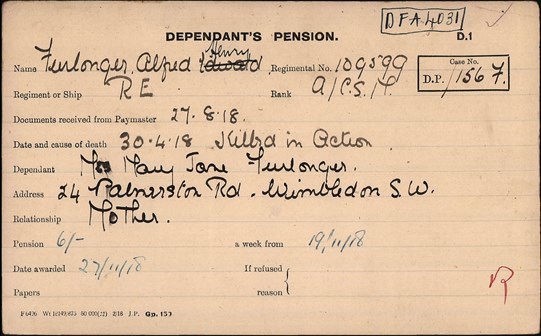

Above: The Pension Card for Furlonger

L/Cpl. J. E. Bigland survived, although he was seriously wounded. Spr. J. H. Woodman was the 5th man awarded the Albert Medal in this incident, but he escaped uninjured.

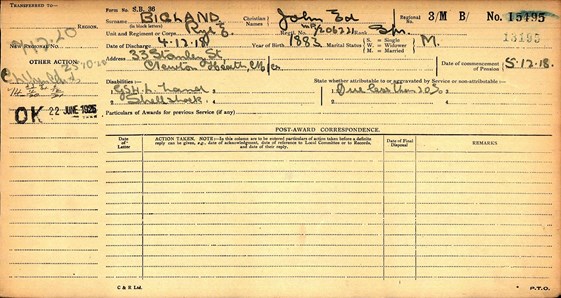

Above: The Pension Ledger for Bigland

A Royal Flying Corps incident

Another incident involving a store of ammunition being at risk of exploding is related below. Again there were a number of recipients who were awarded the Albert Medal.

On the 3rd January, 1916, at about 3 p.m., a fire broke out inside, a large bomb store belonging to the Royal Flying Corps, which contained nearly 2,000 high explosive bombs, some of which had very large charges, and a number of incendiary bombs which were burning freely. Major Newall at once took all necessary precautions, and then, assisted by Air Mechanic Simms, poured water into the shed through a hole made by the flames. He sent for the key of the store, and with Corporal Hearne, Harwood and Simms entered the building and succeeded in putting out the flames. The wooden cases containing the bombs were burnt, and some of them were charred to a cinder.'

Above: Alfred Simms

Above: The medal group belonging to Alfred Simms

Cpl Hearne was - like Simms - awarded the Albert Medal as was Air Mechanic Harwood and Major Newall. Interestingly Newall was appointed Chief of the Air Staff, the military head of the RAF from 1937, however following the end of the Battle of Britain, he retired and was replaced as Chief of the Air Staff by Sir Charles Portal.

Above: Air Chief Marshal Sir Cyril Newall

Australian, New Zealand and Canadian posthumous awards.

The award of the Albert Medal was made posthumously to one Australian, one New Zealander and two Canadian servicemen during the war. As related above, some of these awards are not detailed on the entry with the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, the citation for Sgt David Coyne of the 31st Battalion, Australian Imperial Force being a case in point.

Above: Sgt David Coyne

The citation, which appears in the London Gazette is as follows:

On the night of 15 May, while in the line at Vaire-sous-Corbie, Coyne was testing some Mills grenades which he believed had been affected by damp. He threw one of them but it rebounded off the parapet and fell into the trench in which he and several others were standing. Ordering his men out, he tried to find the grenade in the darkness; then, realizing that his companions were not clear, deliberately threw himself over the grenade's approximate position and received over twenty wounds when it exploded. At first it was thought that Coyne would survive and it was typical of his courageous and genial nature that he joked about the incident as he received preliminary medical attention. His wounds proved worse than expected and he died within hours.

Above: The original grave marker and the replacement permanent headstone at Vignacourt British Cemetery

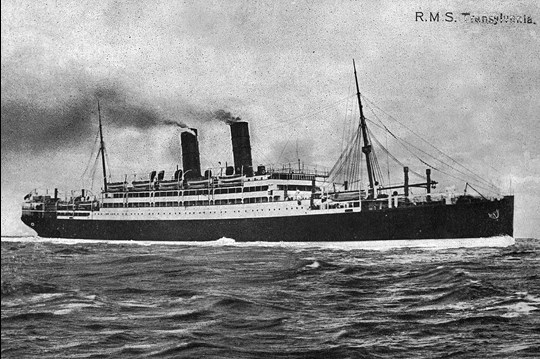

The award made to James Magnusson of the Auckland Mounted Rifles, N.Z.E.F. is one of those made for 'saving life at sea'. The troopship ' SS Transylvania was sunk on 4 May 1917 by a German submarine off the coast of Italy causing the deaths of over 400 soldiers and sailors on board. The citation for his award reads as follows:

Magnusson, who was on the deck of the Transport, saw an injured soldier struggling in the water, and immediately dived overboard, although there was a very rough sea, swam to his assistance, and succeeded in placing him in a boat. Magnusson then returned to the sinking ship and rejoined his unit. His life was lost.

Above: The Transylvania

A survivor of the Transylvania Walter Williams tells the story of the sinking in this Imperial War Museum interview:

(Williams served with the 14th Motor Ambulance Convoy, Army Service Corp on Western Front, 1915-1916 and with the 905 Motor Transport Coy, Army Service Corps in Egypt and Palestine)

The two Canadians who were posthumously awarded the Albert Medal earned theirs in the same incident which took place in Halifax, Nova Scotia in December 1917. Considering the catastrophic loss of life,[2] this is really not widely known. In this accident, a cargo ship (the Mont Blanc) carrying a large quantity of explosives (including TNT, picric acid, benzol and guncotton) collided with another ship in Halifax harbour. The full story is told in the article here: The world’s largest pre-atomic explosion: Halifax Harbour 1917. Both were crew of HMCS Niobe.

Above: A view of Halifax Harbour shortly after the 6 December 1917 explosion that killed some 2,000 people. HMCS Niobe can be seen making smoke, beside the tall chimney on the right.

Two members of crew of H.M.C.S. 'Niobe' lost their lives while trying to extinguish the flames on the Mont Blanc. Niobe's crew - realising the danger to the city - made a desperate attempt to prevent the ammunition exploding. Their names were Petty Officer Ernest Beard and Boatswain Albert Mattison. Their citations are identical:

'On the 6th December, 1917, the French Steamer with a cargo of high explosives, and the Norwegian Steamer "Imo" were in collision in Halifax Harbour. Fire broke out on the "Mont Blanc" immediately after the collision, and the flames very quickly rose to a height of over 100 feet. The crew abandoned their ship and pulled towards the shore. The commanding Officer of H.M.C.S. "Niobe," which was lying in the harbour, on perceiving what had happened, sent away a steam boat to see what could be done. Mr. Mattison and six men of the Royal Naval Canadian Volunteer Reserve volunteered to form the crew of this boat, but just as the boat got alongside the "Mont Blanc" the ship blew up, and Mr. Mattison and the whole boat's crew lost their lives. The boat's crew were fully aware of the desperate nature of the work they were engaged on, and by their gallantry and devotion to duty they sacrificed their lives in the endeavour to save the lives of others.

Above: The Albert Medal for Saving Life at Sea awarded to Edmund Ernest Beard © Canadian War Museum,Tilston Memorial Collection of Canadian Military Medals, CWM20130162-001

The Albert Medal continued to be awarded in the inter-war period to those who saved others' lives. It was awarded during the course of the Second World War, but the 'Albert Medal in Gold' was abolished in 1949 (due to the George Cross - which was instituted in 1940 - more or less replicating the criteria for the award). The Albert Medal (the original bronze/second class version) was eventually discontinued in 1971. Recipients were offered the opportunity to exchange their medals for the George Cross. Of the 64 who were eligible to do this, 49 did so.

David Tattersfield, Vice-Chairman, The Western Front Association.

Notes:

[1] The article is not intended to cover the history of the medal, which is quite complex and evolved over time. It originated in 1866 for saving life at sea, but eleven years later extended to saving life on land as well.

[2] Around 2,000 - mainly civilians - lost their lives with a further 9,000 injured.