Stereography in the Great War (in three parts) Part I

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Stereography in the Great War (in three parts) Part I

PART ONE

Stereography in the Great War Part I: Paper card manufacturers by Ian Ference [This article first appeared in Stand To! (122 April 2021 pp. 36-41)

Stereography, which for the purposes of this three–part article series can be easily understood as ‘the depiction of objects in 3D on flat surfaces’, existed before photography did. As soon as photography came into existence, stereoscopic photography evolved in parallel. Early stereography was generally done in a 3.5x7 inch format and viewed through a stereoscope (either hand–held or tabletop). In the 1850s, stereography entered its first ‘golden age’, largely as a result of Queen Victoria’s love of the strange new format. By the end of the 1860s, the costs of producing and obtaining stereography led to a sharp downturn in the practice, and the fad effectively died out. By 28 June 1914, stereography in the United States and in the British Empire was experiencing its second golden age, due to the propagation of inexpensive hand–held stereoscopes and the Underwood model of distribution. Meanwhile, throughout continental Europe, the 1890 invention by French inventor Jules Richard of small, hand–held cameras to create glass–plate diapositives [1] made stereography accessible, for the first time, to amateurs and professionals alike.

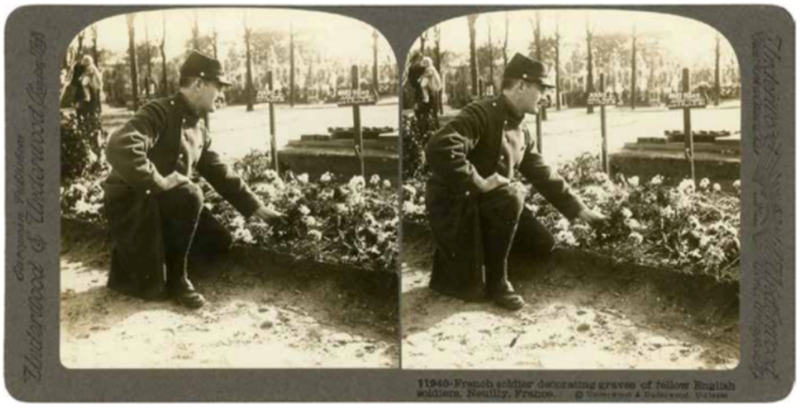

While certain conflicts, notably the American Civil War, the Russo–Japanese War, the Second Boer War and the Boxer Rebellion had been captured on stereoscopic photographs (referred to as ‘stereoviews’, the above image is a stereoview), the First World War was the first – and only – conflict in which hundreds of thousands were produced. [2]

Of these, over ten thousand were commercially duplicated and sold in most combatant nations. During the ‘stereoscopic dark age’ which began with the Great Depression and ended with the View–Master and Stereo Realist colour formats, and which encompassed the Second World War, the vast majority of non–commercial Great War stereography disappeared. Gone too was much documentation on the commercial stereoviews. What remained was largely shoved into basements or attics and forgotten about. While some universities and museums have reasonably large quantities of Great War stereography, much of it is incorrectly processed, with negatives scanned backwards and apocryphal information in the finding aids. While this is understandable given that the hobby of collecting stereography has carried with it an oral tradition that has kept the stories alive, it is important to note that as with any oral tradition, the narratives shift over time, and bits of the story get lost along the way.

The Boyd/Jordan/Ference Collection (https://greatwarin3d.org; hereafter simply ‘the Collection’) is the largest publicly available Great War stereography collection in the world and attempts to preserve this forgotten material culture of the First World War, in addition to digitising it. As of this writing, nearly 10,000 stereoviews are available on the website, with tens of thousands more on their way. Additionally, it is a goal of the Collection to verify and codify the oral traditions of the stereoscopic community regarding the use of 3D photography in the Great War. Even the ‘Bible of Stereography’, William Culp Darrah’s The World of Stereographs [3] has as much errata as actual fact. [4]

The author of this article and current curator of the Collection was offered over one hundred unique stereoviews in return for postage from a Frenchman who was just about to toss them in the rubbish before stumbling across the site. In the estimation of Doug Jordan, the previous curator, it would be ‘miraculous’ if five per cent of the amateur stereoviews produced by Continental photographers were still extant. [5]

In this article, the history of the major and minor paper card stereoview manufacturers will be laid out, along with the qualities, negative and positive, of each manufacturer. The following article will focus on commercial glass stereography in a similar fashion, as well as exploring limitations at the front. The third article will concern itself with amateur stereography of the Great War, the urgent need for preservation of this unique material culture, and how cohesive amateur collections can ‘fill in the blanks’ left by commercial manufacturers.

Difficulties of creating negatives for paper card stereoviews

Whereas an SPA stereographer [6] in France needed only make room in their rucksack for a Richard–format camera and 40 unexposed glass plates (about the same size and weight as two tins of bully beef), the paper card stereographer needed an entire pack horse. Rather than fitting into a rucksack, the camera was as large as one, being effectively two 4x5” large format cameras tethered together. A large wooden tripod was needed to hold these cameras, and generally a stereographer would carry over 100lbs of dry plates to create negatives on, the phytochemicals needed to develop the negatives in preparation for shipment back to London or the United States, and dark cloths or changing bags appropriate for loading film and developing plates.

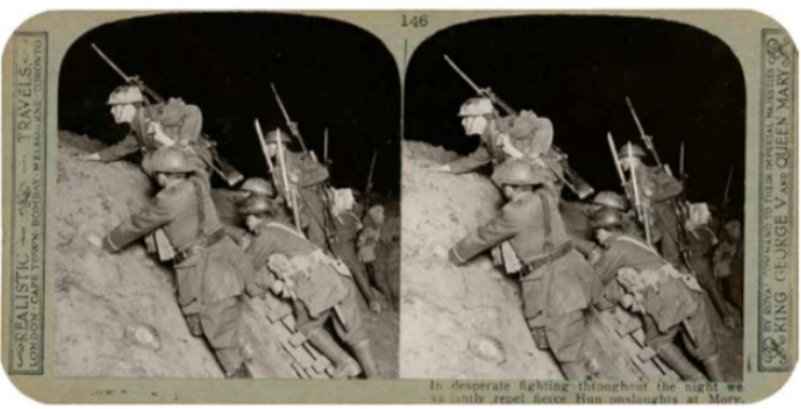

While these constraints were no deterrent in travel stereography, the genre most paper card stereographers were trained in, they were not well–suited to wartime stereography. Along with the constraints imposed by bringing a stereographer’s field gear ‘along for the ride’, the camera had to be as near–to–level as possible; having the lenses at a tilt made for unpleasant viewing. Setting up quickly and capturing an action shot was next to impossible. While there were significant limitations imposed by combatant nations on photography at the front (to be discussed in the following article), these further limitations led to a wealth of paper card stereography that is generally devoid of front– line action or difficult terrain. There are no paper card stereoviews of the Italian campaigns against the Dual Monarchy in the mountains for the simple reason that it was treacherous enough to get a soldier, his supplies, and his rifle up there; hundreds of pounds of stereographic equipment was out of the question. Thus, like the tableaux above, easily recognisable as a simulacrum for actual combat stereography, most manufacturers had to rely on scenes staged behind the lines, or in training camps thousands of miles away.

Paper card stereoview manufacturers Underwood & Underwood

After the decline in stereography during the 1860s, it appeared to be a fading technology. In 1861, Oliver Wendell Holmes had invented, and deliberately not patented, a handheld stereoscope capable of holding 3.5x7” paper card stereoviews, the most commonly used format in Anglophone countries, then and now. Inexpensive to produce, and demonstrating decent optical qualities, the Holmes Scope made collecting stereoviews an accessible hobby for the middle class. Bert and Elmer Underwood realised that there were vast, untapped markets for stereography some time in 1881. Incorporating a door–to–door canvass method for sales, in which potential customers could experience stereography first–hand, caused the company to quickly take off. Soon, they moved towards industrialisation. Instead of hand–printing each stereoview in a small studio, they leased large buildings with large bays of windows, and long tables at which workers (mostly female) would make contact prints, to be mounted, captioned and packaged, assembly–line fashion. U&U was the largest stereographic concern in the world by the turn of the century, producing a staggering 25,000 views a day. It was then that they devised a new direction for their marketing. While they would still market individual stereoviews to customers, they devised the notion of canonical sets, released under the ‘Underwood Stereographic Library’ series. Sets of cards, all relating to a single subject, would be arranged in sequential order, often in groups of 100. They would be housed in cases that resembled pairs of thick, leather–bound books. Actual books, an optional add–on to most of these sets, with further information on each card displayed, were offered to enhance the experience.

In late June 1914, two (possibly three [7]) U&U stereographers were already ‘over there’. Albert K Hibbard rushed to Serbia immediately to capture its army gearing up for war, and when Germany’s intent to attack France was clear, made his way there, before returning to the London office of U&U with ‘hundreds’ of negatives. Meanwhile, a stereographer known only by the initials ‘H J’ was already in Belgium, creating a travelogue set of the country. At the outbreak of the war, H J shifted focus and quickly began documenting what would come to be known as ‘the Rape of Belgium’. Thus, by 1915, U&U was able to provide stunning recent 3D content to Americans through its New York headquarters, and to the British Empire through a separate imprint of their London subsidiary. The early American sets were titled ‘European War’, while the British versions (consisting of a different set of images) were released as ‘War of the Nations’.

U&U stereoview characteristics

Underwood stereoviews from this time period were printed on a pleasant slightly sepia emulsion, which was then pasted onto the stamped cardboard mount to create the finished stereoview. During the early years of the war, most of their output was taken by house photographers, and supplemented with images bought from German manufacturer NPG (discussed below). They managed to cover a good portion of the Western Front, as well as of the South African campaign, but Eastern Front coverage (as with all paper–card manufacturers) is almost non–existent or uses reprinted negatives from the Russo–Japanese War. Post–war Underwood stereoviews are scarce, and tend to focus on monuments, burials, cemeteries, ruins and other scenes of remembrance. Underwood & Underwood ceased all production of stereographs in 1920, so few post–war views exist.

Keystone View Company

Hot on U&U’s heels was young upstart B Lloyd Singley and his Keystone View Company. A U&U canvasser during his aborted collegiate career, Singley started taking his own stereoscopic images in 1892 and decided to form his own company. Singley’s own images were quite unremarkable, ‘Singley, himself, took all Keystone negatives prior to 1897. The quality of the prints is generally mediocre to very poor. The subjects are often trivial, the documentary ones matter–of–fact’.[8] Singley copied the business model of U&U, and by 1900 was churning out views almost as quickly as his former employers. Lloyd Singley was an aggressive businessman, and as soon as he was able, began buying up negatives from other stereographers along with the rights to the images. Only a fraction of these were ever published; Singley’s goal wasn’t necessarily to obtain negatives to print, but rather to stop negatives from being printed by his competitors. After his acquisition of all U&U negatives in 1921, KVC had a virtual monopoly on English–language paper stereoviews.

As opposed to U&U, which had two or three British stereographers covering the war from the get–go, KVC was not allowed to send a stereographer over due to the Allied policy of disallowing Americans from visiting the front, thereby forcing them to use British sources in an attempt to get Americans to side with the Allied Powers when they eventually entered the conflict.[9] The first KVC war stereographer, Andrew S Iddings, reached Europe in late 1918, and his views represented the first original content for KVC – all taken after Armistice. So how is it that Keystone rushed out its first ‘European War’ sets in 1915 and 1916?

Since U&U was able to produce a legitimate set portraying the Belgian, French, British and Serbian war efforts of 1914 early the following year, KVC felt the need to keep up. But without actual stereographers in the field they had to improvise and blatantly falsified captions. KVC re–captioned images from the Russo–Japanese War, the Second Boer War, the Boxer Rebellion and other previous events, as well as using stock images of each combatant nation’s armed forces (usually at least a decade old). Hastily produced, the set of 30 images included captions but lacked verso text; KVC could only carry the fabrication so far.

Over the next eight years, Keystone was continually updating their offerings with negatives acquired from other stereographic outfits, the Iddings negatives and further fabrications. Between 1916 and 1921, over a dozen canonical sets were produced, often for short periods of time. The 1923 300–card set, generally known as the ‘Hanson Set’, was compiled by Major Joseph Mills Hanson. It carefully balanced action scenes with battle–damage and ruins, hospital scenes with remembrance and monuments. This was the first Keystone Great War set to offer an optional book (authored by Hanson) that described in greater detail what the viewer was seeing. It was an instant hit, and went through 5 editions, each with very minor changes, over the ensuing nine years.

1932 saw the release of the final, and definitive, KVC Great War set. Consisting of 400 cards, many with new images bought (or stolen) from French, German and other Continental sources, this set contained many more gruesome images, and removed many of the training–at–home images, which were considered to be of little interest. While it still presented an America–centric view of the war, it was as well–rounded as any paper card stereographic collection would ever get. Unfortunately, it was also an expensive set released in the early years of the Great Depression. The author knows of only about a half–dozen complete sets worldwide, as the set sold poorly during the two years it was in production.

KVC stereoview characteristics

Although they are the most common, and most avidly collected among the major manufacturers of Great War stereography, Keystone stereoviews are arguably the least interesting. All cards are printed on an inexpensive glossy B&W stock; early cards are misleadingly captioned and later cards are largely acquisitions from other manufacturers. The focus of 1919 and later sets is squarely on America’s greatness, how America single handedly came in and decided the outcome of the war, and quite a few major topics are glossed over or skipped entirely – including early French and Belgian battles, Gallipoli, Passchendaele, Verdun and so on. The Hanson book, while interesting as an American perspective on the war, is jingoistic to the point of being a false history.

While this Iddings stereoview was part of the Keystone negative collection before even the acquisition of the Underwood catalogue, it was not published until 1932 – after Singley had effectively retired from the business in the late 1920s, leaving it to two colleagues to run (Author).

The treatment of Black American soldiers

The treatment of Black American soldiers in American paper card stereography bears mention; KVC and, particularly, founder and first stereographer B Lloyd Singley’s overt racism [10] becomes apparent when tracking change amongst the various sets. No set produced during the war contained a single depiction of ‘coloured’ troops; the first two stereoviews depicting Black American soldiers appeared in the 1919 set of 200. One depicts Black soldiers washing dishes after mess, while the other depicts Black soldiers obediently lined up and ready for inspection by their white CO. This is a stark contrast to their primary American Competitor; U&U produced nine stereoviews of Black soldiers during the war, portraying them heroically, and even directly calling them ‘heroes’ in a 1919 stereoview depicting their return to America. Keystone used some, but not all, of the U&U negatives in later sets, and images of Black troops taken by Iddings were suppressed until the 1923 set (in some cases, the 1932 set). Although U&U stereographers captured the 369th Coloured Infantry (‘The Harlem Hellfighters’), there are no known stereoviews of their most celebrated soldier, Private Henry Johnson, the first American of any sort to earn the Croix de Guerre. In the year following the war, 17 returning Black servicemen were lynched (according to official records) the actual number is likely orders of magnitude higher, since many lynchings were undocumented, and the army records for ‘coloured’ troops are dodgy at best.

H D Girdwood and Realistic Travels

If B Lloyd Singley was the J P Morgan of early 20th century stereography, Hilton DeWitt Girdwood (who shunned his given name and always adopted his initials) was its P T Barnum. Born in Canada, but more at home in India, early histories of Girdwood and the various companies he founded are murky at best. The first known stereoviews published by Girdwood date to 1903, though it is possible that he created work prior to this and sold it to other imprints. At some point before this, like Singley, he canvassed for Underwood & Underwood – using each meeting as his own personal recruitment tool for readers of his fledgling stereographic journal. Making his home in India for almost a decade, he became close friends with a number of Englishmen in high places – among them, James Willcocks [11], who would eventually command the Indian Corps in France.

Realistic Travels

After founding the Realistic Travels imprint, sometime shortly before the war [12], Girdwood began making acquaintance with people in power, often through showing them his work and offering to provide them with stereographic portraits. During the war, his charisma took him well beyond Willcocks. His social climbing ranged from staging scenes of Sir John French ‘commanding’ at GHQ to taking portraits featuring HRH Henry, the Prince of Wales, ‘somewhere in France’. Ingeniously, he had the young prince click the shutter on his camera, and through this obtained the Crown Copyright for all Realistic Travels images – for a short period of time. After repeatedly sneaking up to the front he offended Haig and his Crown Copyright was revoked, and all official connections with the British Army were severed.

Girdwood spent the remainder of the war buying negatives from other stereographers portraying battles he himself had not witnessed, creating dozens of ‘canonical sets’ which often were unique; upon hearing that a potential customer was interested primarily in aviation and naval material, Girdwood would proclaim that he had just the set for that... and create it on the spot. Assigning semi–random numbers to the cards in these made–to–order sets makes tracking down a complete catalogue of every Realistic Travels image of the Great War near to impossible. However, there are canonical sets of 200, 500 and 600 cards that can provide a template to begin a collection from.

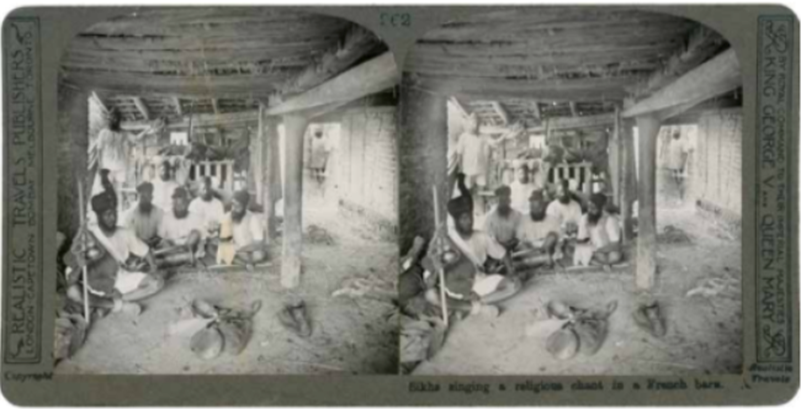

1914 – 15: Embedded with the Indian Corps and obtaining the Gallipoli negatives

As soon as war broke out Girdwood made it his business to document the Indian Corps, while simultaneously sending assistants to other regions of the Middle East and Africa to document the war efforts there – correctly guessing that his soon–to–be rivals at U&U and

KVC would primarily be concerned with the Western Front. It is thus that his imprint created the most impressive (if hard to catalogue) array of English–language paper stereoviews, with broader appeal to modern Great War scholars than KVC or U&U. While the latter two outfits are more widely known and studied amongst stereography scholars, they are of much lesser value when considering the scope of the war on the whole due to the limitations placed upon these manufacturers and the topical limitations they placed upon themselves.

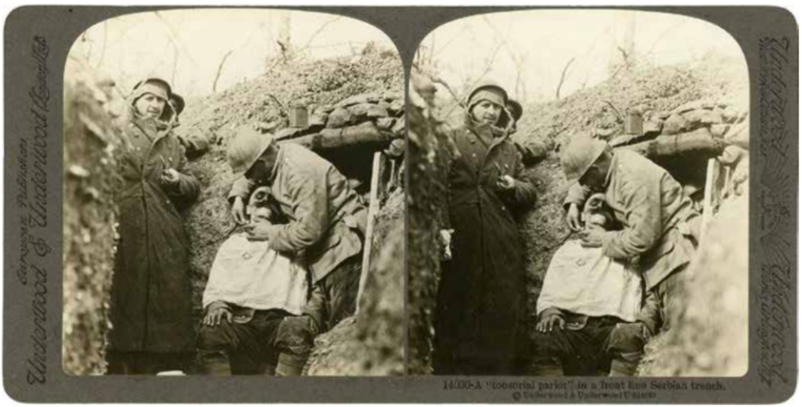

All views of the Indian Corps, as well as views of the Indian hospitals in Britain and France, were taken by Girdwood with the help of at least two assistants. In characteristic Girdwood style, the majority of his 1915 activities were paid for by the Indian government and the War Office, as he was simultaneously filming the silent propaganda film With the Empire’s Fighters. [13] Moving his three large plate–back cameras, tripods, filming equipment, film stock and related ephemera required two pack horses, and he rode alongside them (his assistants had to march). Girdwood took time to study all units within the Indian Corps but had a particular fascination with the Gurkhas. While on the training grounds in France after arrival, Girdwood spent days staging scenes that were anything but ‘Realistic’. Flash stereography with large format cameras of men going over the top at the front would have gotten Girdwood a well–deserved bayonetting; regardless, his staged scenes (including a few of ‘dead’ BEF soldiers all comfortably lying in trenches and fields, with no wounds visible) were as close as one could get to bringing the war into the public’s parlours in 1915.

Meanwhile, Girdwood obtained views from other stereographers, accounting for battles he could not possibly have witnessed (he was probably shooting propaganda for the Indian Office in October 1914; Realistic Travels published views of the Battle of the Yser). His most important acquisition, however, was that of Charles Snodgrass Ryan’s [14] negatives from the Gallipoli campaign. The exact means by which he achieved this coup over larger outfits appears lost to history, although Doug Jordan, previous Collection curator, had a very sensible suggestion. [15] However he got them, they’ve proved to be the most important stereoscopic record of early ANZAC operations, documenting key personnel, Lord Kitchener’s visit to Anzac Cove and so on. The other manufacturers didn’t bother to compete with Realistic on Gallipoli; it was one of many subjects that only the strange and charismatic Canadian bothered to cover in his output.

1916 – 1964: Completion of canonical set, world tours, fade into obscurity

After being booted from the army, Girdwood devoted himself entirely to the production of Realistic Travels cards and the promotion of With the Empire’s Fighters. He toured with the film until the war’s end, all the while acquiring new stereoscopic negatives from various sources. It should be noted that the film was shot in order to bolster recruitment efforts in India, but by the time it was processed, India was being mined only for the Indian Labour Corps. One of the sources of new negatives was the British offshoot of his former employer, Underwood & Underwood; at least a few negatives were sold to Girdwood instead of KVC. [16]

After Armistice, Girdwood returned and captured new stereographs of monuments, ruins, cemeteries and other remembrance themes which make up a full sixth of the 600–card ‘Official Series’. It appears as if this series was the basis for all future Realistic Travels cards; Girdwood had offered smaller canonical sets during the war, but as previously mentioned, most of them did not correspond with any sort of consistent organisation. After the assembly of the ‘Official Series’, smaller subsets were produced in numbers of 500, 300, 200, 100, 50 and 32. Unlike earlier sets, which were often provided to customers in repurposed U&U boxes, the ‘Official Series’ sets had an elegant two–book façade.

Sometime after 1924, the last year in which correspondence indicated that Girdwood was still actively involved with Realistic Travels, he settled in London. He reappeared briefly in 1939 to offer his service as a propagandist to the Indian Office at the outbreak of the Second World War. After reviewing his files, presumably still laden with vitriol from Haig, he was turned down. Girdwood died in 1964 in Michigan, USA, in complete obscurity. Those relatives which have been located in recent years have no idea as to the whereabouts of his negatives, his documentation, his film or anything else.

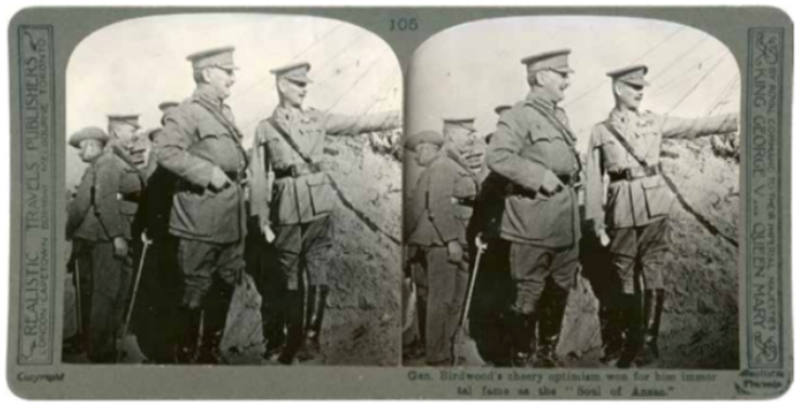

A Charles Snodgrass Ryan image of General Birdwood, taken at Anzac Cove, June 1915, and later published by Realistic Travels (Author).

Realistic Travels stereoview characteristics

Girdwood printed his stereoviews on at least four distinct mount stocks, although the paper was always of the highest quality. Using a high–silver emulsion, Realistic Travels stereoviews really ‘pop’ when placed next to the works of U&U and KVC. While there is an ‘Official Series’ of 600 cards, and many smaller series derived from it, it is important to note that there were almost certainly over 1,000 negatives published, that captions are inconsistent and because of the number of changes to the sets, the card numbers are virtually meaningless unless they have remained in order for roughly a century. Each card bears an official–looking stamp which reads: ‘By Royal Command to Their Imperial Majesties KING GEORGE V and QUEEN MARY’, almost certainly as a means of associating Realistic Travels with his self–defined persona as the ‘official stereographer’ of the British Empire.

Despite his bluster, shenanigans and generally seedy tactics, Girdwood managed to acquire a set of negatives that was more comprehensive, more interesting and generally more complete than those of his primary rivals. Featuring everything from the naval raids at Zeebrugge and Ostende to the mealtime needs of the Indian Corps, Realistic Travels produced

the best record of the British war effort. It should be noted that his coverage of French Army subjects, the Eastern Front and other non–British war efforts was minimal. Yet, while people have been collecting and cataloguing KVC and U&U views for many decades, it’s only in the past decade that any serious efforts have been made to document and catalogue Girdwood’s work. There are at least three serious undertakings occurring at the moment, including one by the author, to create timelines, lists of printed negatives, details of sets and a more complete portrait of Girdwood himself.

Minor paper card manufacturers

In addition to the three ‘giants’ many smaller outfits produced paper card stereoviews. A comprehensive examination of all of them is more suited to a monograph than a journal article; covered below will be five that might be of particular interest to Western Front Association members. Specifically, not included are manufacturers of inferior or uninteresting views and manufacturers who primarily offered glass stereoviews and printed a subset as paper cards (these will be covered in the second article).

Geo Nightingale & Co

There is very little information available as to the origins of George Nightingale’s operation, based in Weston Super–Mare, Somerset. The cards exclusively depict post–war images. 200 are known to exist, split between two confusingly named sets of 100: ‘The Battle Field Series’ and ‘The Battle–Field Series’, the hyphen being the only identifier (although the two series are completely distinct). The company appears to have been set up specifically to give employment to ex–servicemen, as explicitly stated on each card. Themes covered are generally battlefields, war damage and memorials. A significant portion of both series are centred around Flanders and the Somme. The cards consist of thick, unmounted photographic paper, with verso text.

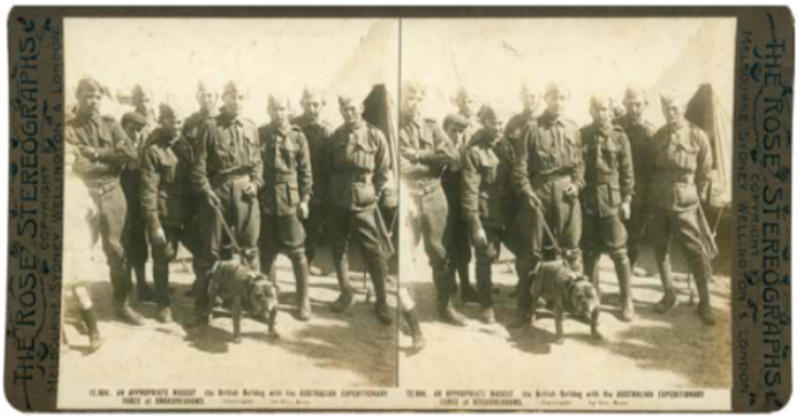

Rose Stereograph Company

George Rose founded Australia’s most prominent stereography outfit in 1880, at age nineteen. Over the next 40 years, Rose would produce 26,000 stereoviews, over 10,000 taken himself. During the Great War, he and his associates produced 56 stereoviews17 which are now considered essential to the stereoscopic documentation of the ANZAC war effort. Like most manufacturers, Rose was not able to get stereographers up to the front. However, he was uniquely positioned to capture the AIF in training in their home country, something that no other stereoscopic outfit offered. The views of training at Broadmeadows, outside Melbourne, are particularly sought after. Rose sold a handful of negatives to KVC, which used three in its definitive 1932 set of 400.

Paris–Stéréo

Bob Boyd’s research notes from 2007 open with perhaps the best summation of Paris–Stéréo: ‘[n]othing is known about this company beyond what can be inferred from its products’. Like most French manufacturers, Paris–Stéréo’s records were destroyed by the Third Reich. Of the French manufacturers, Paris–Stéréo was the only one whose primary medium was paper, although they produced glass versions of at least a portion of their catalogue too. Overall production stood at around 400 unique stereoviews, 237 of them dating to the early days of the war (1914 – early 1915). They are of very good technical quality, and cover a wide range of topics, although surprisingly no views of Verdun are included.

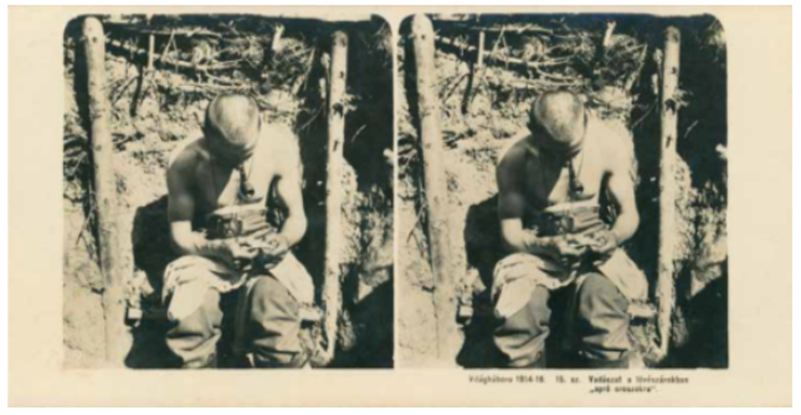

Neue Photographische Gesellschaft (NPG)

The importance of NPG’s documentation of the Central Powers during the war cannot be understated. While it is unknown exactly how many views were created, it is estimated that there were approximately 600 printed, covering a wide range of subjects. Unlike Anglophone manufacturers, NPG’s wartime output was mixed with ‘journalistic’ stereoviews of the times, and there is disagreement in the stereoscopic community as to whether, for example, the 10–card series documenting Franz Joseph’s state funeral ‘count’ as Great War cards. In either case, inasmuch as there were some canonical sets from NPG, 400 German–language cards and 100 Hungarian–language cards (with all but 17 overlapping) are considered the core of NPG’s output.

About a quarter of their output was devoted to the Dual Monarchy; Austro–Hungarians

were always depicted in a positive light, despite the fact that by 1916 they were largely viewed as a burden. Like much German propaganda of the time, they depicted their ‘fair treatment’ of French, Belgian and British prisoners of war – while mocking the Russians rather ruthlessly. The cards are of universally fine quality, printed on single sheets of thick glossy stock rather than mounted.

Feldstag–Verlag (HEGI)

Early on in the war, NPG had some competition from minor manufacturer Feldstag–Verlag, (often referred to as HEGI). They are singular among manufacturers discussed in this article in that they used a small format stereocard and proprietary scope. Their views are focused on the early years of the war, and they’re the only manufacturer known to have captured flying ace Captain Oswald Boelcke in stereo. Aviation was a major topic, and like most commercial stereoviews, none depict actual combat. Because of their small size and the limitations of early 20th century emulsions, detail is sadly lacking in the cards.

Considerations on paper card stereography in modern Great War studies

Given that we know many Great War paper card stereoviews were entirely staged, some were of pre–war subjects with misleading captions and some are entirely uninteresting in their subject matter, is there value to the modern Great War scholar in studying these artefacts? The answer to this question is that it depends on the scholar and their field, but in any case, while they are not as interesting as glass stereoviews (the subject of the next article), there is a lot that can be learned from the formats included in this article, as well as from other minor manufacturers and amateur paper views.

Consumers of news in Anglophone countries generally had access to the same base stock of images, after the Allied Powers convinced America to use British imagery. However, we can trace the prevailing attitudes of the upper–and middle–classes in Anglophone nations by the shift in captioning of particular images over time. For example, in 1915 and 1916, KVC generally referred to the Germans as ‘the Germans’, as America was a putatively neutral country at this point. However, by 1918, they were ‘the Hun’ and generally portrayed in a negative light. The shift in tone from ‘here are some views of that war in Europe’ to ‘here are some views of our allies and enemies’ directly tracks from comparative analyses of these sets. Millions of these cards were printed, and by tracking change, one can draw conclusions about the attitudes of the intended viewers. This is not limited to Anglophone stereography; France and Germany each produced stereoviews, and these reflect the prevailing attitudes in these nations, from the early years to the monuments in France being constructed contemporaneously with the rise of the Third Reich.

It is also worth noting that while the viewing of a photograph, lithograph, newsprint reproduction etc are largely passive tasks, stereography forces active engagement. It is fundamentally an interactive medium, especially given that the viewer must manually change cards to view different scenes, a far more engaging task than flipping pages in a picture album. Even staged stereographs provide an immersive experience that mirrors (without accurately portraying) events like going over the top in darkness or preparing for a coming cloud of chlorine gas.

Stereography can also provide the means with which to reconstruct a scene in much greater detail than flat photography. Since paper card stereography was almost always created with two lenses at standard interocular distance18, it is possible from a single stereoview and modern depth mapping software to ascertain distance between objects, relative scale of objects and other factors that could be instrumental to studying the spatial relations of the artefacts. Thus, for example, it would be possible to create a faithful scale replica of the Place de la Concorde in early 1919 from the Fasser Collection, which will be discussed in detail in the third article in this series.

By way of conclusion, commercial paper card stereography might not provide an accurate representation of the Great War, but that does not diminish its value in terms of understanding prevailing social attitudes, particularly as regards the public perception of the war. Over a century on, they provide an immersive experience not felt when viewing standard ‘flat’ photography. As long as the viewer keeps in mind the constraints of commercial paper card stereography, it is still a valuable and unique record of the times. As we will see in the second part of this article, commercial glass stereography, which provides a much more visceral and honest view of the war, is of far greater interest to those looking for new insights into the conflict, although there were limitations and constraints there too. Finally, in the last article in this series, we will examine amateur stereography (both on paper and glass substrates) and note how its lack of constraint makes it the most exciting and important use of stereography during the First World War.

The author would like to acknowledge some people without whom this article would have been impossible (or at least, much more difficult). First and foremost, his mentor and dear friend Doug Jordan (1961–2020). Additionally, Ralph Reilly, Paul Bond, David Starkman and Stacey Doyle Ference, who lent their knowledge or their eyes on early drafts. Ian can be contacted at stereoscope@westernfrontassociation.com.

References

1 Diapositives are positive images – much like photographic slides – printed onto transparent substrates (glass, polyester, celluloid etc).

2 Pers. Comm. Doug Jordan, 22 October 2018. Unless otherwise noted, all Pers. Comm. citations refer to in–person discussions, phone conversations or emails with Doug Jordan.

3 William C Darrah, The World of Stereographs, (Land Yacht Press: 1977).

4 A glaring example of this is Darrah’s timeline for H D Girdwood’s Realistic

Travels company (p 52); Darrah asserts that Realistic Travels existed from 1908 until 1916. In fact, cards printed as late as 1912 didn’t bear the Realistic Travels name, and although Girdwood’s Crown Copyright was revoked in 1916 and he was banned from the front, it is provable fact that he continued to obtain negatives and print new cards under the Realistic Travels imprint until at least 1924.

5 Pers. Comm. 30 August 2018.

6 Section photographique de l’armée, formed by Papa Joffre in 1915 – issued over 200 stereo cameras and boxes of dry plates for use by French officers.

7 Pers. Comm. 23 December 2018. Doug mentioned his strong suspicion that there was a third stereographer embedded with the Serbian armed forces, accounting for the dozens of known images taken of these combatants. If Hibbard’s views accounted for the 1914 images from Serbia, then someone else must have taken the 1915 views of the combined French and Serbian forces. If this is the case, his name appears to have been lost to history.

8 Darrah (1977), p 48.

9 Steve Burch, Dennis Casey and Lori Alaniva, Reluctant Spies (Lackland Air Force Base, Texas: Air Intelligence Agency, 2001).

10 Sample captions from caricature stereoviews of Black Americans created by Singley himself include: ‘Now, I’se got the idea fo’ Bicycle, Suah’, ‘How much ob dis road am you ‘titled to, suh?’, and ‘Negroes Picking Cotton on a Plantation in Texas’, the last being a nod to the effective continuation of chattel slavery in the United States due to Jim Crow laws and pervasive systemic racism.

11 General Sir James Willcocks, GCB, GCMG, KCSI, DSO, died 18 December 1926.

12 Evidenced by the fact that all cards from 1912 and prior bore the imprint ‘H D Girdwood’, and every stereoview produced in 1914 or later bore the ‘Realistic Travels’ imprint

13 This film was a flop on the British Isles, but a minor hit in India. There is still hope that a copy of it exists in some dusty vault or will appear at an Indian boot sale, much as several lost episodes of Doctor Who have been recovered in recent decades.

14 Major General Sir Charles Snodgrass Ryan, KBE, CB, CMG, VD, died 23 October 1926.

15 As it turns out, Snodgrass Ryan was back in the UK with typhus around the same time that Willcocks was preparing to resign his command, and that the former’s mention of his stereoscopic photography caused the latter to set up a meeting with his friend Girdwood. As the negatives were published under the Realistic Travels imprint by 1916, by which point Girdwood was back in France and Belgium, this timeframe seems to make the most sense, although of course it is merely conjecture.

16 Bob Boyd’s research notes, unpublished.

17 Completely catalogued and described, Ron Blum, George Rose: Australia’s Master Stereographer, (Griffin Digital, 2011), pp 196–199.

18 Generally 62–64 mm.