Summoned by Bells: Duke Niall and the Inveraray Bell Tower

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Summoned by Bells: Duke Niall and the Inveraray Bell Tower

Nial Diarmid Campbell, (1872-1949) the 10th Duke of Argyll and MacCalein Mor was, to say the least eccentric, and became known as “Scotland’s Most Picturesque Duke”. An antiquarian totally immersed in his Clan history, he had other many interests, including horticulture and stamp collecting, but mainly the Celtic church, doctrine and the architecture of church buildings. He avoided innovations like the motor car, put off installing electricity and had no telephone, but also had an adventurous streak, setting off on long journeys on his bicycle. He strongly defended his sometimes radical ideas, could be argumentative, rude and confrontational, but there is no doubt that he had a genuine and deep affection and concern for the extended family of his clan and the people working and living on his vast estates.

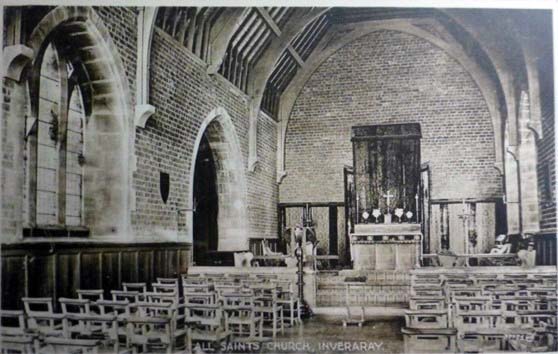

He had taken an intense interest in the war and had been Honorary Colonel of the 8th Argyll & Sutherland Highlanders since 1914. Throughout the war he maintained correspondence with military and political contacts, clan members, estate workers and local people. When the war ended, he was determined to raise a memorial to the lost members of his clan, his unusual idea a reflection of the man’s interests; his determination to circumnavigate problems and achieve his ambition a reflection of his personality. What he wanted was a peal of bells for All Saints’, a small church in Inveraray. Unlike his ancestors, the Duke was very High Church and worshipped there, always taking great interest in the way the church was managed and how it looked.

All Saints Episcopal Church in Inveraray (close to the ancestral castle), was designed for Amelia, the 8th Duke’s second Duchess. She was a devout Episcopalian and wanted a better building for Episcopal services which were then being held in the old parish school. In 1885 the 8th Duke granted a feu for the erection of the new church and appointed Sir Robert Rowand Anderson of Wardrop & Anderson as architect. Anderson had previously worked for the Duke on Iona Abbey and designed Mount Stewart House, the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh and other prestigious buildings, so it was, for him, a minor project. The modest church is built of pink granite rubble with pink Ayrshire freestone dressings and has pointed Gothic arches. There is a large vestry and an organ chamber. The building was completed in September 1886 and a parade through the town began the opening ceremony. The church itself owes much to the generosity of the 10th Duke, who took great interest in both worship and the business affairs of the church.

The memorial plan was to proceed in stages, each to be funded by donations. The first was purchase of the bells, the second building a frame to hold them, the third a tower to house them. After the tower was complete, the bells would be raised to the top. It was hoped to then join the tower to the church as it was to be erected adjacent to, but separate from, the building. The final stage would be the consecration of the tower and bells.

The Bells

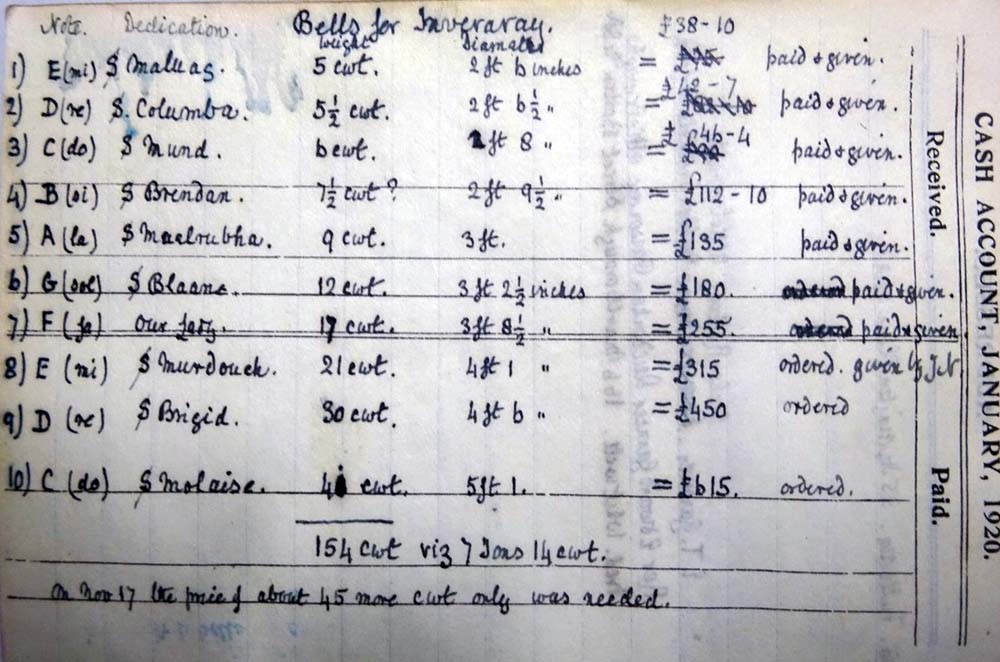

The choice of a peal of ten bells was ambitious, and would form the heaviest peal in Scotland, and apart from those at Wells Cathedral, the heaviest in the country and therefore the second heaviest peal of ten in the world. Each bell was given a saint’s name and inscribed accordingly. Details of the bells follow below.

Before transport was improved, many cathedral cities and large towns had bell foundries, but the numbers reduced and following the war there were few left. One outstanding firm was that of John Taylor of Loughborough of Leicester, a bell founding business which began in 1780 but had roots from the mid-14th century. The firm was chosen to cast and deliver ten bells for Inveraray.

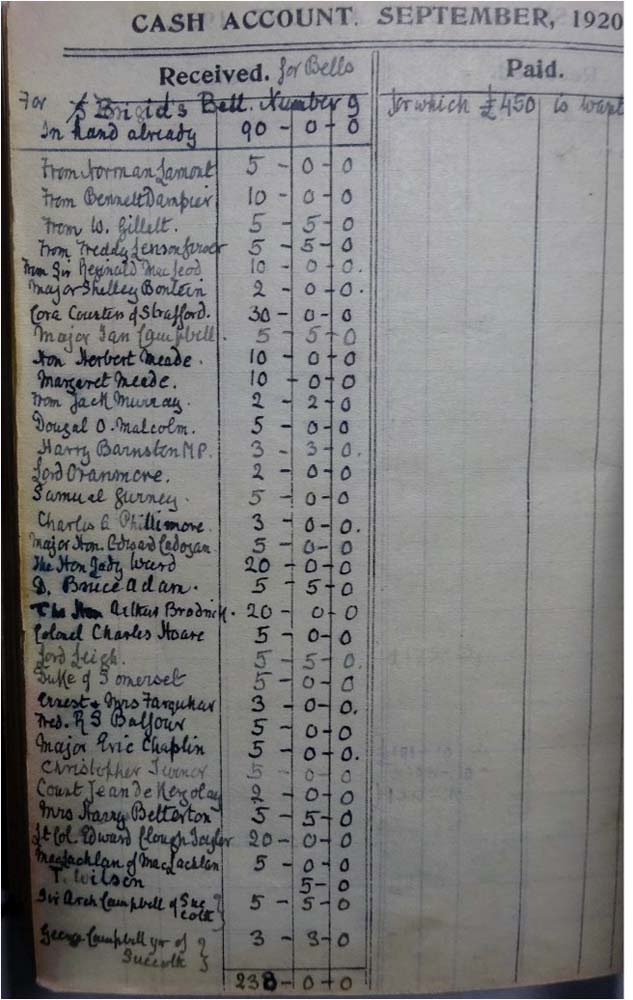

The provision of such a large and impressive set of bells was very expensive, (£2,422/17/6) and before appealing for donations the Duke started the ball rolling by donating money in 1918 and 1919 to cover the cost of the most of the bells. He paid for seven bells, and the remaining bells were paid for by subscribers. There were other costs too, all carefully noted by the Duke in his little red notebook now held in the Argyll & Bute Archive. The progress of the work was dutifully recorded in his diary and mentioned frequently in his extensive correspondence.

Additional costs included costs for the epigrams, the wheels, fittings, a steel frame, and the chiming gear as well as the transport from Loughborough. The red notebook gives details of the extra money needed:

- Epigraphs £26/6/0

- Fittings and chiming gear £505

- Steel bell frame £850

- Wheels (to be kept at Loughborough until needed) £97

- Carriage and erection I shed near the church £375.

Duke Niall again stepped forward with his chequebook and paid £307 for the equipment for 7 bells, with donations from others paying the costs for the remaining 3 bells. With the cost of the bells at £2,422/17/6 this amounted to £4,276/3/6 (over £250,000 today. It was all paid off by the beginning of January 1922.

The ten bells for the tower were cast in Loughborough by John Taylor’s company and brought to Inveraray in 1921 to be housed in a wooden shelter until the building was ready. The inscriptions were written by a friend of the Duke, Professor John S. Phillimore, who graduated from Christ Church, Oxford, a contemporary of Duke Niall. After converting Phillimore became the first Catholic professor of the University of Glasgow since the Reformation. The men were both interested in church dogma, history and discipline and corresponded regularly.

Bringing Home the Bells

Because of the weight a strong foundation for the temporary home was needed for the temporary wooden shelter. The site needed clearing, and the Duke rolled up his sleeves to remove the rushes before workers set in cement the stones which would support the bell frame. It had to be strong, as the total weight would be almost 20 tons. The Duke’s Aunt Fanny, (Frances Callander) a nun who was deeply interested in the project, was kept fully informed of progress.

After leaving the Loughborough foundry, the lorry broke down and a new one was provided for the long journey. On 1 November 1921 the Duke heard that the Bell Hanger and Mr Billinghurst from Loughborough would be at Inveraray on 3 November to prepare for the arrival of the bells. It was all taking longer than he hoped, but he was happy that everything was ready regarding the foundations. He met Mr Billinghurst at the pier at 2.30 and took him to the George Hotel, then at 3.00 they went to see the site of the bell frame. All was well but a wooden floor was required to support the bells and avoid the mud while the frame was erected. The first lorry loaded with the smaller girders and the smallest bell would arrive on Saturday 5 November. The heavy girders and the other bells would follow in trailers pulled by powerful engines. Frustratingly, the Duke had to leave for Edinburgh where, on 6 November, he heard that St Mund’s bell and some of the steel girders had arrived that afternoon and Mr Gibson told him that it caused great excitement at the Avenue. He wrote to his Aunt Mary (known as “Froggy” and wife of the Bishop of Peterborough) that he thought it ” a curious thing that the first to arrive should have been the patron of the Clan” (St Mund).

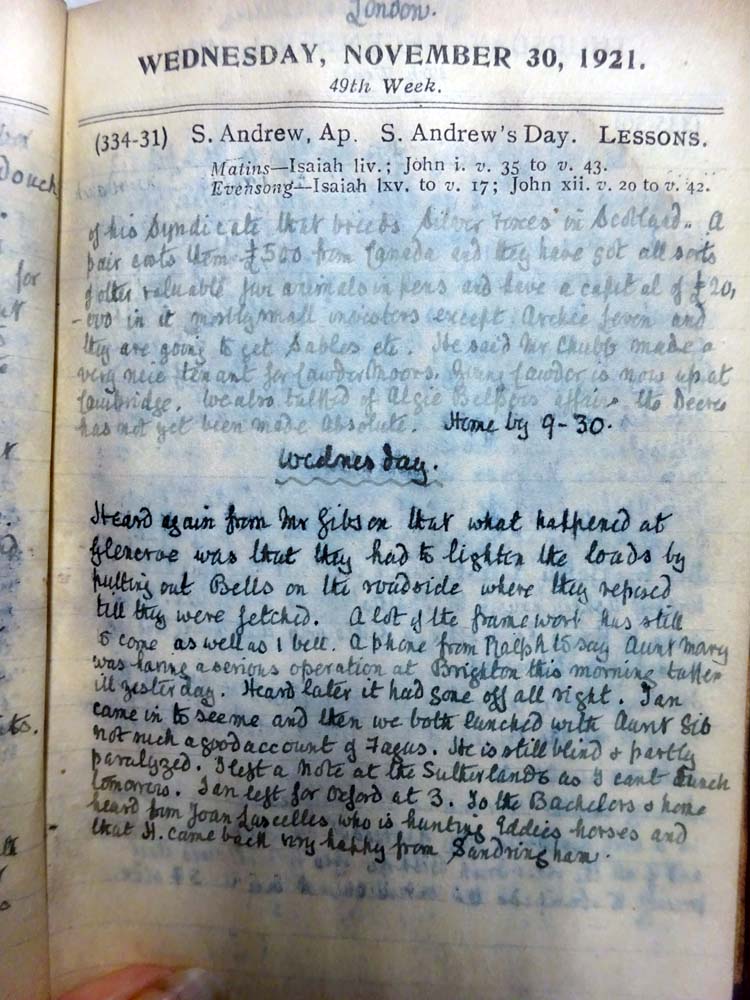

By 26 November, the Duke was in London and feeling relieved to learn that the bells of Brigida, Molaise and Maelrubha had arrived, but that he had been informed by the Rector that the other two lorries carrying the other bells were stuck in Glen Croe, one at The Rest and one at The Little Rest. He comments:

“all have crossed the Marches of Argyll”

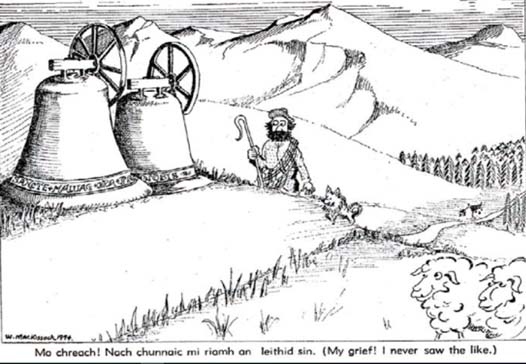

Transporting over 7 tons of bells and fittings in the 1920s, especially over narrow and steep roads was no easy matter and there was a mammoth challenge at the Rest and Be Thankful (A83) with its very steep slopes, hairpin bends and landslides. Problems are still very common today and in gone by days there were also delays on the troublesome road. At the time of delivery road was blocked, and some astonished travellers helped unload “Murdouche”, weighing over 20 cwt, to reduce the weight on the lorry. The bell was left behind and the lorry delivered the others to Inveraray, returning the following day to collect their jettisoned load. There was still additional material for the bell frame yet to arrive. The grapevine was frantic; one rumour declared that the bells were actually giant beehives for the Duke’s Estate.

The Duke reported a detour one of the bells made:

“Taylor by the way had not heard of the transport people’s folly over going with one bell to Inverurie”.

The residents of the town, on the other side of the country in Aberdeenshire, were surely puzzled. It added almost 300 miles to an already long and difficult journey.

Before the end of 1921 all the bells were in Inveraray, sitting on their frame in the wooden hut. On Christmas day Duke Niall chimed them for the first time at Midnight Mass. The bells would remain in their temporary home for another 10 years.

In January 1922 Nial was in a snowy Inveraray and on 3 January he walked to the Avenue and rang the bells This was done from a keyboard. He reported that the roof of the temporary building was nearly ready for the slates. His diary records that he had recommended the firm to Dr Cram of Yale University. Taylor of Loughborough wrote thanking him and sending him photographs of the huge ring of Yale bells, including a 7-ton Tenor bell.

The Bell Tower

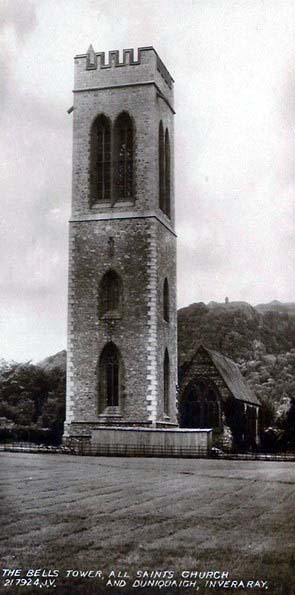

It was always a requirement to have a special tower to house the bells, and the plan was to attach it to the church itself. Building the tower took from 1923–1931, but the planned extension to link the church with the tower was never completed.

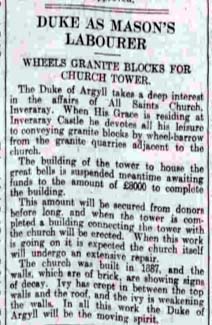

This was an important personal project for the Duke who himself carried stones for the tower in a wheelbarrow, climbing a ladder to lift each to the correct level. He faithfully recorded the progress in his diary. The press were delighted with the eccentricity of a Duke doing heavy manual labour and his efforts were featured in several newspapers. As he kept the clippings he must have been pleased with the publicity!

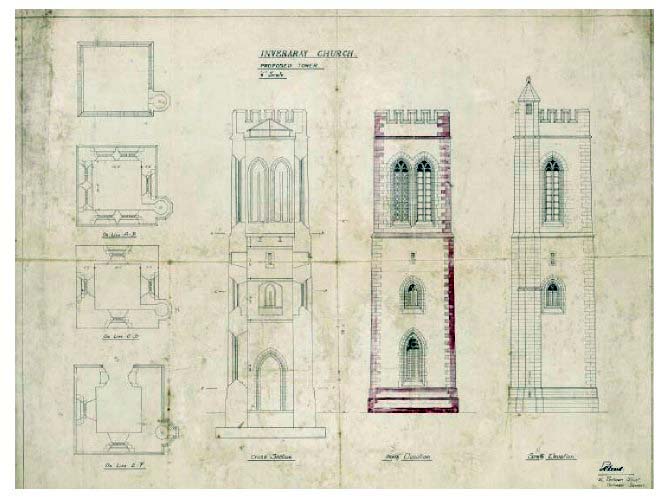

Throughout the 1920s the fundraising continued, and he asked his architect friend Edward Hoare to draw up plans for the belfry. He was pleased with the details of the plan produced by Hoare and Wheeler of London and noted that a wooden model was being made. Tenders were sought, and Hoare chose the lowest estimate which was from Mr George Reid of Ayrshire. The work began in October 1923 with removal of the turf and preparation for the foundation. An area 60ft square 15 ft deep was dug by 12 labourers, revealing old wooden pipes and patches of gravel. Niall recorded in his diary:

“Cunningham had to pump hard after a wet night.”

After six weeks of back-breaking work they had not reached solid rock and so decided to put in concrete reinforcements, taking sand from the shore and bemoaning the lack of extra carts to speed them up. At last, building the tower started in 1924, progress was slow but by the end of the year it was 44ft high. After spending almost £10,000 the money ran out and the build was halted for the next five years.

The fund-raising campaign was renewed, with appeals to friends, family and clan members all over the world. Every time the Duke gave a speech he asked for contributions, and among his personal correspondence many letters enclosed small donations. Money came from Harry Lauder, George Bernard Shaw, Lords and Ladies, military men, bereaved families and those who could afford only a little during the years of strikes and hardship. A few letters sent apologies that due to hardship they were unable to support such a good cause. There were collection boxes for visitors to the town, the wooden model on display attracting tourists and inspiring donations. The bells were chimed almost daily, another attraction drawing in visitors.

Meanwhile, Duke Niall continued to collect large stones for infilling the walls, recording a total of 2,674 in 1926. At last building began again in 1930, and after a long holiday in France Niall, on his return to Inveraray, was delighted with progress. The work and skills of the craftsmen impressed the Duke, who knew them all, and showed a genuine interest in the men and their lives. His diary records details of the work, sometimes daily. By August the roof was complete, and at the end of 1931 the final stage of the project was reached with a visit from the bell hangers from Loughborough. On Christmas Eve:

“the church was packed. We had all the tower lit up…and a great Bell display”

The costs were calculated thus:

- The building of the Great Tower:

- First part (1923-1925) Builders £92,00, Architect £552

- Second Part (1930-1932) Builders £6,827, Architect £409/12/0

- Total £16,988/12/0

Including the cost of the Bells, the project cost £21,264/15/6d, with an estimate of almost £1.50 million equivalent today. The Duke’s personal contributions were regular and generous.

The tower has 176 steps leading to the top where there is a splendid view of Loch Fyne and the surrounding countryside. It is 123 ft high, 36 ft wide, the walls at ground level are 9ft thick.

The first peal on the Bells was 6 August 1938, the second in July 1939. The Second World War silenced the Bells. Considerable damage to the stone walls and windows was caused by a lightning strike in November 1944. Stones were thrown into the adjacent field, and local telephones and lights put out. Fortunately, the bells were not harmed. It was wartime and impossible to make repairs. Duke Niall died in August 1949 and the Duke’s fine tower suffered further damage caused by the weather and neglect. There was a possibility that the bells would be sold by the Church to India but the Bishop of Argyll intervened and this was stopped. It was not until 1975 that major efforts to restore the memorial were started. It was designated a Category A listed building in 1980, and grants were made available for the work. A number of contributions were made and the repairs began - by 1994 the work was complete.

The high tower is exceptionally well designed to bring out the wonderful tones of the bells which are a joy to campanologists who consider them one of the finest rings of bells ever cast. It is also a tribute to the dedication of Niall Diarmid Campbell, a devout Highlander determined to honour the sacrifices of “his people” in the Great War.

Other Memorials connected to Duke Niall

In 1920, his diary records:

“Unveiled the Kilblaan War Memorial at 3.00pm. Called about the town (Campbeltown) in the morning then changed out of my kilt into uniform before lunch, taking Mr Lothian with me. I left in my motor for Mr Mac Vicar’s manse at Kilblaan. The cross is about a mile from the Campbeltown side of Kilblaan and we waited until all tenants, at least 1,500, had turned up and mustered at the cross at Keprigan cross roads. Where there was a huge concourse.

After inspecting the Guard of Honour the service began and I gave an address before unveiling the names on the cross it-self which had no covering upon it and the Union Jack merely covered the names let into the cairn.

Spoke to all the fathers and mothers and the other tenants afterwards.

In 1922, The Duke unveiled the town memorial in Inveraray; a Roll of Honour in Inveraray School was unveiled in 1919, and on 4 March 1923 a Celtic cross commemorating the 8th Argyll’s was unveiled at Beaumont Hamel, only yards from the site of the Battalion HQ. The memorial notes that during its service in the field (from 1 May 1915 until the end of the war) 51 officers and 831 NCOs and men were killed. and 105 officers and 2,527 NCOs and men were wounded. A Gaelic inscription on the memorial reads "friends are good on the day of the battle". Niall spoke in English and French, being Fluent in that language.

Article contributed by Ann Galliard

Acknowledgement

This article is based on material held by the Argyll Archive, Inveraray, with thanks to The Duke of Argyll and the Archivist, Cherry Park.