The Battle of the Boar's Head

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Battle of the Boar's Head

Lord Kitchener's famous call for volunteers 'Your Country Needs You' resulted in an overwhelming response with hundreds of thousands of men stepping forward. This has often been portrayed as a north of England phenomena. The roots of this misconception may be as a result of the attack made at Serre on 1 July 1916 by 'pals' battalions from Accrington, Leeds, Sheffield and other northern cities.

Just 24 hours before the attack on the Somme was an equally bloody assault by other 'Kitchener' battalions recruited from the south coast of England. This attack, on the 'Boar's Head' position, is now largely unknown.

Inspired by Kitchener's recruiting drive, three 'Southdowns' battalions were raised in Sussex between September and November 1914 by Colonel Claude Lowther, MP of Herstmonceux (East Sussex).

Above: Volunteers of the 1st South Downs Battalion in September 1914, showing their camp at Cooden (adjacent to Bexhill). Note the lack of uniforms. Image courtesy of Paul Reed.

The recruits were nicknamed 'Lowther's Lambs' and after nearly ten months, the three battalions were taken over by the War Office in July 1915. They became the 11th, 12th and 13th Battalions of the Royal Sussex Regiment, and were eventually allotted, together with the 1st Portsmouth Battalion (officially the 14th Battalion, Hampshire Regiment) to the 39th Division.

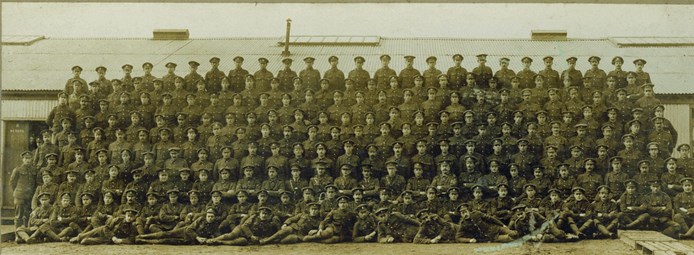

Above: 'A' Company, 3rd South Downs Battalion; around three-quarters of these men became casualties on 30th June 1916. Image courtesy of Paul Reed.

After arriving in France in March 1916, the twelve infantry battalions of the 39th Division were introduced to the front lines and started 'learning the ropes' of trench routine. An account of this period for the division can be found in Joffrey's War.

Colonel Lowther, the driving force behind the South Downs battalions was too old to serve in France and therefore command of the 1st Southdowns Battalion (11th Royal Sussex) was given to Lt.-Col. Harman Grisewood (born 1879). Two of Harman's brothers were also officers in this battalion: Francis (born 1880) and George (born 1889). George, who was Adjutant of the battalion, had been taken ill with meningitis shortly after they had arrived in France, and died on 27 March.

Harman was determined to look after his battalion, and possibly as a result of this determination he had a difficult relationship with the brigade commander who has been appointed soon after the division arrived in France. Following dinner at brigade headquarters one evening, a raid on the Germans was demanded, this to take place within 24 hours. The author Neville Lytton details this:

Grisewood jibbed a bit at the short notice, but said that he would immediately make a personal reconnaissance. This he did, but discovered that the lie of the land was extremely complicated and he informed the Brigadier [Brigadier-General ML Hornby] that the raid would not be successful unless he had three or four days for preparation. The Brigadier was furious..."

Neville Lytton, The Press and the General Staff (1920) pp 38-39

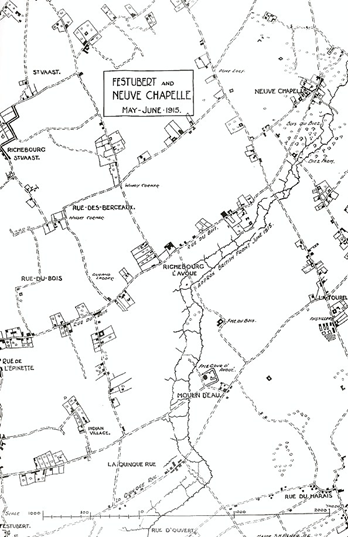

Richebourg l'Avoue

The British preparations for the Battle of the Somme (which was originally scheduled to commence in June 1916) were obvious to the Germans, and it was felt that it would be useful to try to divert German attention away from the Somme area. It was therefore decided that an attack in the area of Neuve Chapelle may be worthwhile.

Above: Map of the Boar's Head area. (Click on the map to enlarge)

Consequently, the untried units of the 39th Division were instructed to prepare to attack at the German salient known as the Boar's Head, south-east of Richebourg l'Avoue.

Initial plans had been made which involved the 11th Battalion leading the attack, with the 12th Battalion on their right, and the 13th Battalion in reserve. When he saw the plans, Lt.-Col. Harman Grisewood, expressed serious misgivings that if his untried troops attacked over unfamiliar ground a disaster might result. He is reported to have informed his brigade commander: “I am not sacrificing my men as cannon-fodder!”

This was probably the last straw for Brigadier-General Hornby who no doubt reported this insubordination to the divisional commander. Harman Grisewood was promptly sent home on leave. Nevertheless, the preparations for the attack continued. Neville Lytton describes the build-up:

Our shooting was shockingly bad and our heavies never touched one of these [concrete gun] emplacements, a fact which I reported regularly every night and morning. The Germans, on the other hand, knocked our line about considerably, and the fire on both sides was so intense that no sleep was possible for eight days that I held the line prior to the attack.

Neville Lytton, The Press and the General Staff (1920) pp 40-41

Having lost faith in the 11th Battalion, the plans were changed and the 12th and 13th Battalions led the attack, on either side of the Boar's Head salient. The 11th were to be in reserve.

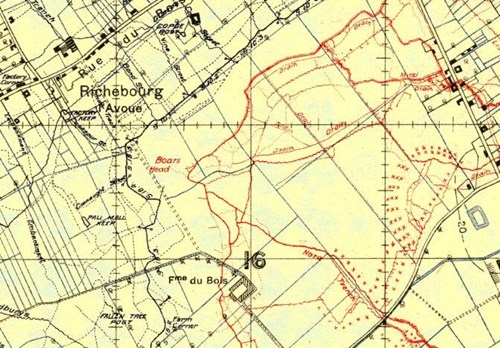

Above: Trench map of the area dated September 1916, courtesy of Great War Digital

The two battalions assembled at 1.30am on the morning of 30 June in readiness for the attack.

Extract from Report on Operations, 13th Royal Sussex, 30 June 1916:

The preliminary bombardment on the morning of the attack opened at 2.50am and at 3.05am the leading wave of the battalion scaled the parapet, the remainder following at 50 yards interval. At the same time the flank attack under Lieutenants Whitley and Ellis gained a footing in the enemy trench. The passage across no man's land was accomplished with few casualties except in the left companies, which came under very heavy machine-gun fire. The two right companies succeeded in reaching the objective but the two left companies only succeeded in penetrating the enemy's wire in one or two places. Just at this moment a smoke cloud, which was originally designed to mask our advance, drifted right across the front and made it impossible to see more than a few yards ahead. This resulted in all direction being lost and the attack devolving into small bodies of men not knowing which way to go. Some groups succeeded in entering the support line, engaging the enemy with bombs and bayonets and organising the initial stages of a defence. Other parties swung off to the right and entered the trench where the flanking party was operating, causing a great deal of congestion. On the left the smoke and darkness made the job of penetrating the enemy wire so difficult that few if any succeeded in reaching the enemy trench. Some parties of the right company succeeded in reaching the enemy support line when they were subjected to an intense bombardment with HE and whizzbangs. Captain Hughes, who was wounded, seeing that his company was in danger of being cut off, gave the order for the evacuation of the enemy trenches and the remainder of the attacking force returned to our trenches. The enemy who was evidently thoroughly prepared now concentrated his energies on the front line and for the space of about two and a half hours our front and support lines were subjected to an intense bombardment.

Returning from his enforced leave, Lt Col Harman Grisewood was relieved of command, he was able however, to send a message to the men of his battalion:

“In relinquishing the command I have been so proud to hold during the past fourteen months. I wish to record my gratitude to each and every man in the battalion for the loyal co-operation they have given me in the great work we undertook together and so to express my appreciation of all the assistance each has rendered. The battalion has earned a great name and a splendid reputation and I know they will add to a record of glory and bravery worthy of the regiment to which we belong. The memory of the two years we spent together will always be with me, and to everyone in the battalion I wish God’s speed and good fortune.”

Behind this message was a personal tragedy for Harman: his younger brother, Francis Grisewood had been killed in the attack. Francis was farming in Australia when war broke out, but had returned to the UK as soon as possible, joining the battalion his older brother commanded. Francis has no known grave and is named on the Loos Memorial to the Missing.

Above: Francis Grisewood. Image courtesy of King's College London

Victoria Cross

One Victoria Cross was awarded for valour shown during the attack on the Boar's Head. Nelson Carter was born at Eastbourne in 1887 and enlisted, aged 15, in the Royal Field Artillery. Within a few months he was discharged as being medically unfit, but in 1906, now aged 19, enlisted again, serving for three years before once more being discharged on health grounds.

When war was declared in 1914, Nelson joined the Southdowns Battalion, and in view of his previous experience, was promoted to Corporal on the same day. He was given further promotions, first to Serjeant and later Company Serjeant Major. It was probably as a result of one of these promotions that he was transferred to the 2nd Southdowns Battalion (12th Royal Sussex Regiment) with whom he was sent to France. The following was written to Nelson's wife by an officer:

When I last saw him he was close to the German line, acting as leader to a small party of four or five men. I was afterwards told that he had entered the German second line, and had brought back an enemy machine gun, having put the gun team out of action. I heard that he shot one of them with his revolver. I next saw him about an hour later ( I had been wounded in the meanwhile and was lying in our trench). Your husband repeatedly went over the parapet. I saw him going over alone and carrying in our wounded men from 'No Man's Land'. He brought them in on his back, and he could not have done this had he not possessed exceptional physical strength as well as courage. It was in going over for the sixth or seventh time that the was shot through the chest. I saw him fall just inside our trench.

Above, CSM Nelson Carter, VC. Image courtesy of Paul Reed. (C) Carter Family

At least two sets of brothers were killed during the course of the 30 June attack. James Honeysett (aged 36) and Cecil Honeysett (29) were from Bexhill-on-Sea and members of the 3rd Southdowns battalion. Also in the 3rd battalion was Leonard Blaker (aged 29) and Frank Blaker (27) from Worthing.

In the 2nd Southdowns battalion was Private John Searle, who volunteered for the army in April 1915, aged just 14 years old. John was from Durrington (Worthing) and was posted as missing after the attack on the Boar's Head. He has no known grave and is commemorated on the Loos Memorial to the Missing.

Above: Private John Searle, "the youngest of five brothers serving". Killed at the Boar's Head, aged 15. Image courtesy of The Royal Sussex Living History Group / John Baines

Where are the men from the South Downs buried?

Of the 344 fatalities incurred in the three South Downs battalions on the 30 June recorded by the CWGC over half have no known grave and therefore the names of these 187 'missing' are, like John Searle, commemorated on the Loos Memorial. A large proportion of the rest are buried at St Vaast Post Military Cemetery. A total of 73 identified men from the Royal Sussex attack are known buried in Plot 3 of this cemetery. This is an original battlefield plot created during the war.

Some 16 miles to the south of the Boar's Head is the Cabaret Rouge British Cemetery at Souchez. Here are buried 68 identified men from the Southdowns Battalions (inevitably a number of the unknowns will also be men from these battalions). The vast majority are buried in plot 15, rows N, O and P.

The Southdowns men now in plot 15 were all originally buried at Illies German Cemetery within a large trench grave and had a German cross. A Graves Registration Unit cross commemorating the '84 unknown British soldiers and the 7 unknown British officers who had died on the 30 June 1916 and were buried in this grave' was added later.

Above: Cabaret Rouge British Cemetery.

After the war, it became possible, through official histories, associated artefacts and research to place names and identities on a number of the unknown casualties contained in this trench grave. They were then concentrated into Cabaret-Rouge, in the 1920s, with named headstones rather than ones to unknown soldiers.

When they were reinterred at Cabaret-Rouge a superscription was added to the majority of the headstones in rows O and P reading “believed to be buried at this spot”. Whilst the evidence from research and artefacts suggested that they were the correct casualty, this could not be confirmed with identity discs. All of those who were later buried in row N were all identified using their identity discs and their graves therefore do not have the superscription engraved.

Other men from the attack are buried in small clusters in cemeteries close to the scene of the Boar's Head, including three known and identified men at the Royal Irish Rifles Graveyard, Laventie. One of the men buried here is CSM Nelson Carter, VC, who was mentioned above.

'Undertones of War'

One of the classic accounts of the First World War is by the soldier/poet Edmund Blunden; a schoolboy in 1914, by 1915 he was serving as a 2nd Lieutenant in the 1st Southdowns battalion. Major GH Harrison, who took over the battalion after Grisewood, became an admirer of Blunden’s writings and also a firm friend. Blunden was one of the diminishing number of old soldiers who survived the war and lived into old age, passing away in 1974.

Above: Apparently the last reunion of the Southdowns Battalions Association, which took place on 12 May 1979. Image courtesy of Southdowns Battalions

Further reading:

- Baines, John The Day Sussex Died : A History of Lowther's Lambs to the Boar's Head Massacre (2012).

- Lytton, Neville The Press and the General Staff (1920).

- Bourne, JM and Bushaway, Bob (editors) Joffrey's War - A Sherwood Forester in the Great War (2012).

- Blunden, Edmund Undertones of War (1928).

- Paul Reed will be publishing a new book which will include the phenomenal amount of work he has already put into research the attack on the Boar's Head by the Southdowns battalions. The book will be coming out in 2016, prior to the hundredth anniversary of the battle.

Acknowledgements:

I am grateful to the following for their help with this article.

Paul Reed: The Boar's Head

John Baines and The Royal Sussex Living History Group: The Day Sussex Died

David Lester: Southdowns Battalions

Article by David Tattersfield