The Disaster at Hooge

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Disaster at Hooge

One of the most frequently heard misconceptions about the First World War is that British and Commonwealth generals and their staff officers shared neither the hardships nor the dangers of the average front line soldier. The excellent Bloody Red Tabs by WFA members Frank Davies and the late Graham Maddocks has been an important rebuttal of these arguments, detailing seventy eight generals who were killed in action or died of wounds. The book also provides biographies of a further 146 generals who were wounded, or became Prisoners of War. Although Bloody Red Tabs was published over twenty years ago, the fact remains that public perception is still dominated by the “Lions Led by Donkeys” approach.

Whilst this article is not intended to examine the arguments around the subject of generalship (there is not room for a full examination of the arguments) those who wish to delve deeper into the waters of this controversial subject can do so via the links which are provided at the end of this article.

Arguably the worst single incident of the First World War in terms of the near destruction of command and control of British Divisions was the height of the First Battle of Ypres. At this stage in the war the Germans were pressing the British and Commonwealth troops back and it was felt that a breakthrough by the Germans was possible. Had this occurred, the way would have been open to the channel ports: this would have spelled disaster for the Allies.

Against this background, the commanders of the British 1st and 2nd Divisions (Lieutenant General Sir Samuel Lomax and Major General Sir Charles Monro) had requisitioned, in October, the Chateau at Hooge, just outside Ypres as a suitable place for their headquarters.

The chateau was only two miles from the front line. By lunchtime on 31 October, it was becoming clear that the British front line had been broken in one or two places, and immediate action was needed to stabilise the situation.

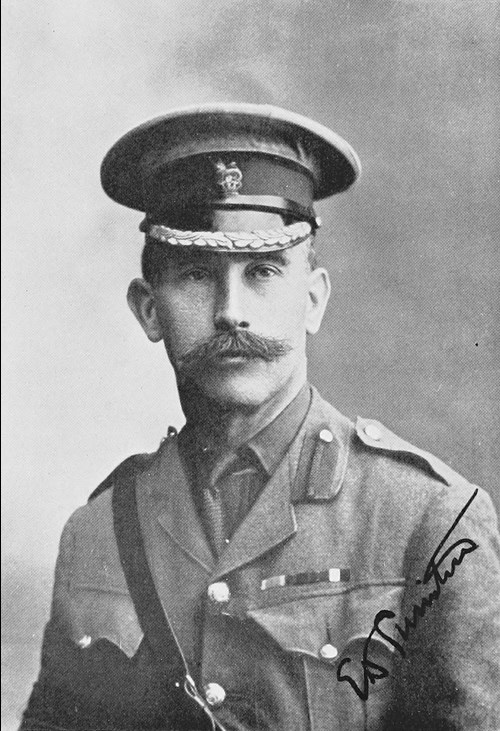

Lieutenant-Colonel (as he was at the time) Ernest Swinton wrote in his book Eyewitness:

As I drove away, I turned around to look at the Chateau of Hooge standing a little to the north of the road. The approach was packed with cars – a splendid advertisement to catch the eye of any chance enemy airman who happened to wander above and proclaim that here was a British headquarters.

Above: Swinton

It may not have been necessary for the cars to be spotted by aerial reconnaissance because the Germans had control of ridges to the east and the concentration of cars must have caught their attention. A German aeroplane flew over the chateau, but this failed to alert the staff of the headquarters to possible danger, and work continued in a room overlooking the gardens.

At about 1.30pm the first shell fell in the chateau gardens. Many of the occupants of the room rushed to the French windows which opened onto the gardens. It seems that still the danger of the situation did not occur to those present. Major General Sir Charles Monro however, took advantage of the distraction to consult with his GSO1 (Chief of Staff), Colonel Robert Whigham in a doorway to the adjoining studio.

Above: Monro

This act probably saved both of their lives, as a second shell burst close to the French windows; the metal tore through the room causing massive casualties. A third shell hit the chateau causing damage but no more injuries (some accounts suggest four shells fell in this salvo).

In the moments after the shelling, the high number of casualties was obvious. Sir Samuel Lomax was critically injured and was evacuated to a Casualty Clearing Station. Sir Charles Monro was severely concussed but otherwise unhurt.

Above: Hooge Chateau some weeks after - roofless and a semi-ruin

Destruction of the First Division command structure

Besides the incapacitation of Lt-General Lomax, his GSO1 (Chief of Staff) Colonel F W Kerr [i] was killed as was the second most senior staff officer of the division (GSO2) Major George Paley.

Above: Kerr

Above: Paley

Lt-General Samuel Lomax was evacuated back to the UK but was to die of his injuries six months later; he was one of the most senior general officers to be killed in the Great War.

Above: Lomax

Second Division decimation

The 2nd Division’s staff was also badly affected: Colonel Whigham (Monro’s GSO1) was rendered unconscious, but otherwise unhurt (he was the only officer of the two staffs to escape serious injury).[ii]

Lt-Col Arthur Percival (GSO2 of the 2nd Division) was killed, as was the Division’s third senior staff officer (GSO3) Captain Rupert Ommanney. Major Francis Chenevix Trench[iii] (who was a staff officer with the Division’s artillery) was also killed.

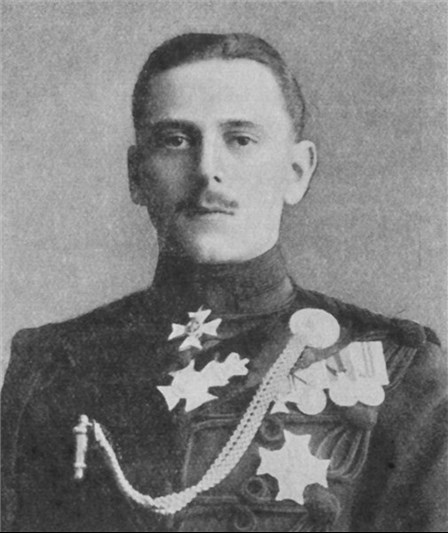

Above: Whigham

Above: Percival

Above: Chenevix Trench

Other staff officers of the 2nd Division were seriously injured; the Commander of Royal Engineers, Lt-Col RHH Boys was wounded,[iv] as was Major I W Forsett and Lieutenant H M Robertson.

Two other officers were severely injured, Captain Graham Shedden of the Royal Garrison Artillery and Captain Robert Giffard (Lomax’s A.D.C.) both died of their injuries.

Above: Shedden, and a memorial to Captain Shedden in St Mildred's Church, Whippingham, Isle of Wight

Above: Giffard

Ypres Town Cemetery Extension

The five officers who were killed outright (Percival, Paley, Kerr, Chevenix Trench and Ommanney) are all buried side by side at Ypres Town Cemetery Extension. Shedden and Giffard are also buried in this cemetery, but none of these seven are the highest profile officers to be buried here. Arguably the most high profile casualty of the Great War, Prince Maurice of Battenburg, a grandson of Queen Victoria, is buried just a few yards away.

Prince Maurice

Prince Maurice of Battenberg, KCVO, was born on 3 October 1891. His mother was Princess Beatrice, the fifth daughter and the youngest child of Queen Victoria. The youngest of his four siblings, Maurice resembled his father (Prince Henry of Battenberg who was the son of Prince Alexander of Hesse and by Rhine) who died when the Prince was only four. Although half German, Prince Maurice grew up in England and seemed to enjoy fast cars - there are reports of him being fined for speeding at least twice. When caught driving on Hampton Court Road in May 1914 at the heady speed of 34mph, he was reported as remarking: “You fellows are always out trapping on race days” (he was fined £3). On another occasion when caught at 42mph, he was fined £5 – this offence whilst a cadet at Sandhurst.

Above: Prince Maurice

He qualified from Sandhurst and joined the Kings Royal Rifle Corps. It was whilst serving with the 1st battalion on 27 October 1914 that he was killed. Prince Maurice was hit by shrapnel from a shell whilst leading his men across the road near the Broodseinde Ridge. Although a sergeant tried to administer assistance to the Prince he was found to be beyond any help and died before he could be evacuated back to the Dressing Station at Zonnebeke. The Battalion also lost 5 other officers and 167 other ranks on 27 October.

Although it was the rule for soldiers who were killed in action to be buried where they died, Lord Kitchener was about to make an exception, ordering that Maurice's body to be sent home, but Princess Beatrice asked for her son to be buried alongside his comrades.

[i] Colonel Frederick Walter Kerr was born on 20 May 1867. He was the son of Admiral Lord Frederic Herbert Kerr and Emily Sophia Maitland. Kerr fought in the Boer War and was Deputy Assistant Quartermaster General of the 1st Army Corps between 1904 and 1906, was GSO2 of the Aldershot Command between 1905 and 1906 and was Deputy Assistant Director of Movements, War Office between 1908 and 1912. Kerr became GSO1 of the Scottish Command between 1913 and 1914 and went to France with the 1st Division on the outbreak of the First World War.

[ii] Colonel Robert Whigham went on to have a long and distinguished career. Promoted to Brigadier General he served as BGGS I Corps from December 1914 to July 1915. Later in 1915 (as a Major-General) he was appointed to the role of Deputy CIGS in London. He was GOC 59th (2nd North Midland) Division from June to August 1918 whereupon he took over the 'crack' 62nd (2nd West Riding) Division during the Hundred Days campaign. He commanded one of the divisions of occupation on the Rhine in 1919 and was one of the few commanders of a division in the much reduced post-war army, becoming GOC 3rd Division later in 1919. He was appointed to Adjutant-General (1923-1927) and GOC-in-C Eastern Command 1927 until his retirement in 1931. He may often have reflected on his lucky escape on Halloween 1914.

[iii] Major Francis Maxwell Chenevix Trench was born on 23 September 1879. He was the son of Colonel Charles Chenevix Trench and Emily Mary Lefroy. He married Sibyl Lyon, daughter of Major Alfred Owen Lyon, on 28 March 1914.

[iv] His replacement, Major Charles North was only in his post for one day, being killed on 1 November. Major North’s permanent replacement was appointed on 9 November. This officer, Major Alfred Tyler, was killed after only two days. It is astounding that three officers in the supposedly “safe” staff role of Commander of Royal Engineers were injured or killed within less than two weeks.

Generalship in the First World War: Some links

Some Prominent British Generals and their Fortunes in The Great War - An extensive article by WFA member Dr David Payne.

The Generals. John Terraine's 1982 Address to The Western Front Association

Article contributed by David Tattersfield, MA

Vice Chairman, The Western Front Association