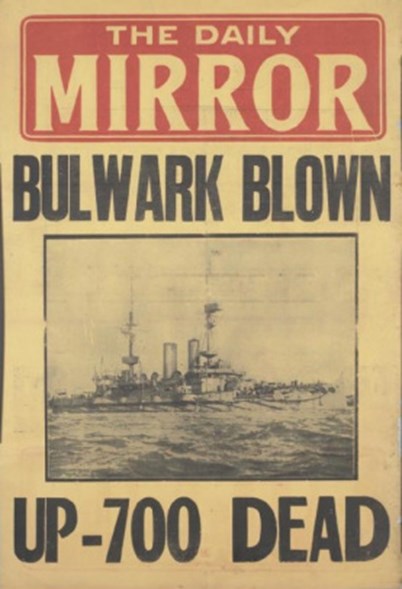

The loss of HMS Bulwark : 26 November 1914

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The loss of HMS Bulwark : 26 November 1914

Losses of life in the First World War are more often than not attributed to engagements in battle or enemy action of some sort. However, this is not always the case. One of the most significant events during the early part of the war that caused a major loss of life to military personnel was an accident.

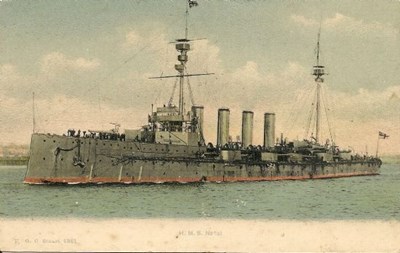

HMS Bulwark was part of the 5th Battle Squadron and at the outbreak of the war was based at Sheerness in order to protect the South East of England from the threat of a German invasion.

Above: HMS Bulwark

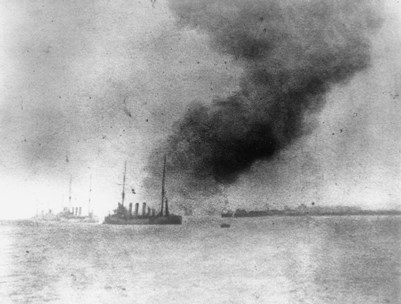

On Thursday 26 November 1914, she was moored in the Medway Estuary approximately between East Hoo Creek and Stoke Creek when, at 7.50am a massive explosion ripped through the vessel. The Times reported

"The band was playing and some of the men were drilling on deck when the explosion occurred. A great sheet of flame and quantities of debris shot upwards, and the huge bulk of the vessel lifted and sank, shattered, torn, and twisted, with officers and men aboard..."

Boats of all kinds were launched from the nearby ships and shore to pick up survivors and the dead. Work was hampered by the amount of debris which included hammocks, furniture, boxes and hundreds of mutilated bodies. Fragments of personal items showered down in the streets of Sheerness. Initially 14 men survived the disaster, but some died later from their injuries. One of the survivors, an able seaman, had a miraculous escape. He said he was on the deck of the Bulwark when the explosion occurred. He was blown into the air, fell clear of the debris and managed to swim to wreckage and keep himself afloat until he was rescued. His injuries were slight.

The CWGC database names 788 men from HMS Bulwark as having lost their lives in this explosion. There was only a handful of survivors.

Above: The aftermath of the explosion of HMS Bulwark.

Of the fourteen men to survive, most were seriously injured. Miraculously there were a very few who came through this without injury, having been blown out of an open hatch. One of these survivors, Able Seaman Marshall described feeling a “colossal draught” and, as he flew through the air, seeing the Bulwark’s masts shaking. Other witnesses were on the battleship HMS Implacable, which was moored next to Bulwark, they described

…a huge pillar of black cloud belched upwards... was followed by a thunderous roar. Then came a series of lesser detonations, and finally one vast explosion that shook the Implacable from mastheads to keel.

Among those killed were six 15 year old sailors: Midshipman William Ellice (who had earned ‘blues’ at Osborne in Rugby, Cricket and Hockey); Signal Boy Benjamin Spencer; Midshipman Evelyn Williamson, Bugler Philip Bullen, Royal Marines; Boy 1st Class William Kellow and Midshipman Charles Wilson.

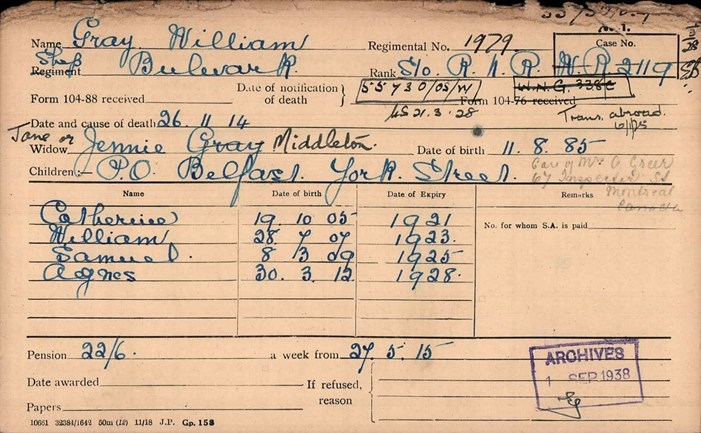

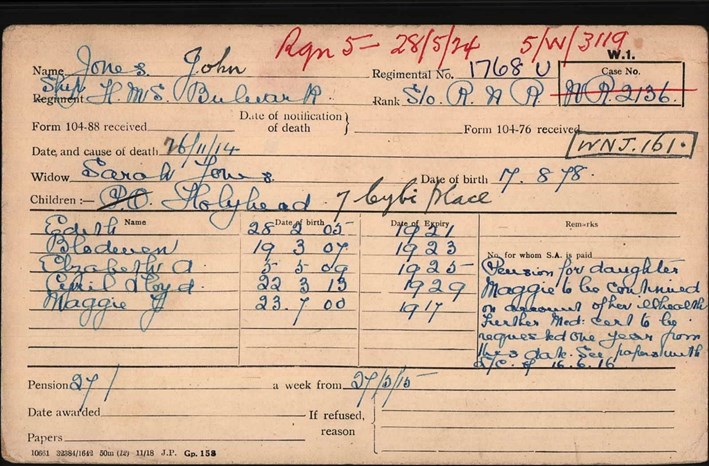

Hundreds of Pension records are provided via The Western Front Assocation's Pension Archive.

Above: Just one of the hundreds of records of men lost when HMS Bulwark exploded.

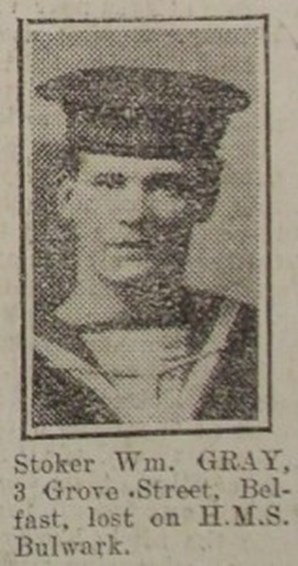

Above: William Gray was one of those to lose his life, and below is his Pension Record Card.

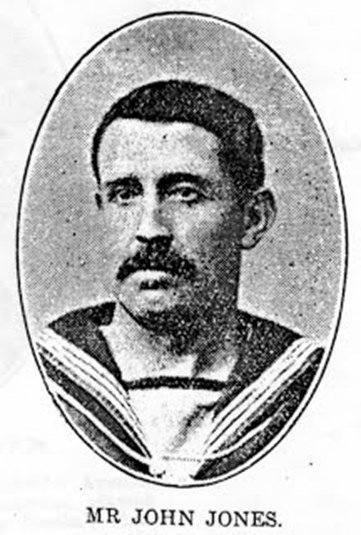

Above: Another fatality was John Jones. Born on 17 February 1874 at Holyhead the husband of Mrs Sarah Jones (nee Roberts) of 7 Cybi Place, Holyhead. In 1901 he resided at 11 Queens Park, Holyhead with 8-month-old daughter Maggie Jane Jones. He had been previously employed for 17 years by the City of Dublin Steampacket Company. At his death he left a wife and 6 children.

On that afternoon, Winston Churchill (The First Lord of the Admiralty) made the following statement to the House of Commons :

I regret to say I have some bad news for the house. The Bulwark battleship, which was lying in Sheerness this morning, blew up at 7.35 o'clock. The Vice and Rear Admiral, who were present, have reported their conviction that it was an internal magazine explosion which rent the ship asunder. There was apparently no upheaval in the water, and the ship had entirely disappeared when the smoke had cleared away. An inquiry will be held tomorrow which may possibly throw more light on the occurrence. The loss of the ship does not sensibly affect the military position, but I regret to say the loss of life is very severe.

The subsequent naval court of enquiry found that shells and other ammunition had been stored in the corridors between the magazines, and that a fault with one of the shells or overheating cordite near a boiler room bulkhead could have started a chain reaction which destroyed the ship.

Most of the fatalities from this incident are named on the Portsmouth Naval Memorial, but 61, whose bodies were located, and could be identified, are buried in Gilliingham (Woodlands) Cemetery.

The inscription reads:

TO THE HONOURED MEMORY OF SEVENTY SAILORS

OF HMS BULWARK TEN OF HMS PRINCESS IRENE

AND BERTIE CLARY A SKILLED LABOURER OF

HM DOCKYARD ALL OF WHOM LOST THEIR LIVES

THROUGH INTERNAL EXPLOSION OF THE TWO

SHIPS OFF SHEERNESS AND LIE BURIED HERE

Princess Irene, mentioned on the Memorial in Gillingham Cemetery, was another Royal Naval vessel which exploded, this disaster rocked Sheerness again, just five months after the Bulwark explosion.

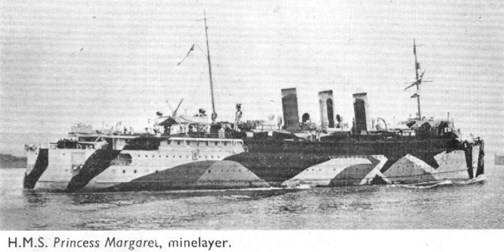

Built in Scotland in 1914, Princess Irene, and her sister ship Princess Margaret were ocean-going liners designed to serve the West Coast of Canada. Both were requisitioned by the Admiralty before they could sail to Canada and were converted into Mine-Layers.

Above: HMS Princess Margaret, which was nearly identical to HMS Princess Irene. Note the dazzle camouflage.

At about 11.15 on the morning of 27th May 1915, HMS Princess Irene was moored at Number 28 buoy about three miles west of Sheerness. Of the Princess Irene’s complement of 225 officers and men, three were ashore that morning. Also on board were a party of 80 Petty Officers from Chatham plus 76 Sheerness Dockyard workers. As the mines were being primed on the ship’s decks, there was an explosion.

Two columns of flames shot to a height of about 300 feet followed by a pall of smoke which hung over the spot where Princess Irene had been – this reached up to 1,200 feet. The explosion destroyed two barges which had been laying alongside her. Although the explosion was larger than that which had destroyed HMS Bulwark the loss of life was less.

Around 350 fatalities were incurred in this explosion, including a nine year old girl who was hit by flying debris; a farmhand and man working on a collier moored half a mile away also died of his injuries when he was hit by flying metal weighing 70 pounds. Body parts and sections of the ship were blown over a wide area, some wreckage being located 20 miles away. There was just one survivor from the Princess Irene.

Evidence at the Official Enquiry showed that the work of priming the lethal mines was being carried out in a hurry and by untrained personnel, although it was believed that there may have been a fault in the primer of one of the mines. Most of the dead are commemorated on Naval Memorials at Portsmouth, Plymouth and Chatham, but seventeen, like the casualties from HMS Bulwark, are buried at Gillingham (Woodlands) Cemetery, including Bertie Clary, a 'Hired Skilled Labourer' (and a civilian employee of HM Dockyard) who is nevertheless commemorated by the CWGC.

Yet another internal explosion caused the loss of a Royal Naval vessel within a few months. On 30 December 1915 HMS Natal was at Cromarty Firth, with a number of civilians on board

Above: HMS Natal

Although a number of the Natal’s 700 strong crew were on shore watching a football match, most of her officers and men were on board. They had been joined by a small part of civilians, who had come on board to watch a film at the invitation of the captain. At 3.25pm a number of explosions racked the stern of the ship.

On this occasion there was a much larger number of survivors, perhaps as many as 300. The five minutes it took for her to capsize was probably crucial in allowing this many to escape. However, losses were still heavy, with up to 420 being killed. Of the 407 officers and men from HMS Natal commemorated by the CWGC, nine named casualties (plus one unidentified fatality) are buried at Rosskeen Parish Churchyard Extensions with a further eight buried at Cromarty Cemetery.

Cromarty Cemetery

The official enquiry into the loss of HMS Natal concluded that it was caused by an internal ammunition explosion, possibly due to faulty cordite.

HMS Vanguard

The explosions in all these ships caused major loss of life, but the biggest single loss of life that was not caused by enemy action seems to have occurred in July 1917 when HMS Vanguard blew up at the Royal Navy’s base for the Grand Fleet at Scapa Flow.

Above: HMS Vanguard

Above: HMS Vanguard

On the morning of 9 July 1917, HMS Vanguard’s crew undertook routine exercises before the ship returned to its anchorage with the rest of the fleet at about 6.30pm. At about 11.20pm witnesses reported

… visible flame coming up from below just abaft the foremast, this being followed, after a short interval, by a heavy explosion accompanied by a very great increase of flame together with a very large quantity of wreckage fragments thrown up abaft the foremast in the vicinity of "P" and "Q" turrets. This explosion was followed after a short interval by a second explosion which considerably increased the volume of flame and smoke (and no doubt debris), but smoke had previously obscured the ship so that the vicinity of this explosion could not be exactly located. The evidence, however, points to it being just abaft the first one.

Report of the Court of Enquiry into the Circumstances Attending the Loss of H. M. S. Vanguard on the 9th July, 1917, from The National Archives, Reference ADM 137/3681

Vanguard had been launched in 1909, being commissioned the following year. She was part of a class of Battleship that had been based on the design of HMS Dreadnaught – a vessel which redefined Battleship design. First Sea Lord Admiral ‘Jacky’ Fisher was determined that Britain would not be ought-gunned at Sea by the rapidly expanding Imperial German Navy, so commissioned a number of classes of Battleships as part of the pre-war arms race with Germany.

Above: Admiral Fisher

Present at the Battle of Jutland, (which took place on 31 May 1916) Vanguard returned to Scapa Flow with the rest of the Grand Fleet in readiness for any future naval action. No action came, and the a routine of exercises and drills were undertaken. With a complement of about 758, it seems from surviving lists, about 95 officers and crew were fortunate enough not to be on board at the time of the explosion, however the CWGC database lists a total of 835 who were killed on 9 July 1917 who were part of the ship’s crew. Of these 621 are commemorated on the Chatham Naval Memorial, and most of the rest on the Portsmouth and Plymouth Naval Memorials. Only seventeen bodies were recovered. Just three men survived the explosion, one of them Lt-Commander Duke died of his injuries a few days later.

Not included amongst those commemorated was Commander Kyōsuke Eto. Eto was a military attaché of the Imperial Japanese Navy and was, in 1916 was assigned as a military observer on board Vanguard.

Above: Kyōsuke Eto being introduced to HM King George V.

Above: Kyōsuke Eto being introduced to HM King George V.

Above: Kyōsuke Eto

HMS Otranto

On 6 October 1918 the HMS Otranto (an armed transport) was approaching the UK when she collided with HMS Kashmir (another troop transporter) in poor visibility and rough seas in the Irish Sea between Northern Ireland and Scotland. The Otranto was transporting US troops as part of the build up of the American Expeditionary Force.

Above: Otranto before the war.

The sinking caused the deaths of 351 US ‘Doughboys’ and eighty British sailors. The destroyer HMS Mounsey managed to take off many troops, thus preventing a much greater loss of life. The British dead are buried at Kilchoman Military Cemetery on the Isle of Islay. The remains of the American troops were also once buried here, but in 1920 the US Government exhumed the bodies and these were either repatriated or reburied in the American military cemetery at Brookwood in Surrey.

SS Mendi

Another troopship was lost, with even greater loss of life in early 1917. The SS Mendi was a steamship chartered by the Government and on 21 February 1917 was passing the southern tip of the Isle of Wight on the last leg of her journey from South Africa to France. On board was 823 members of the 5th Battalion, South African Native Labour Corps.

Above: SS Mendi

Most of the men had never been to sea before and could not swim. In thick fog, the Mendi was inching her way forward, when out of the mist came the SS Darro, travelling at full speed. The Darro was twice the size of the Mendi, and hit the Mendi in the bow, virtually cutting her in two. Because of the list, half of the lifeboats were immediately unable to be deployed.

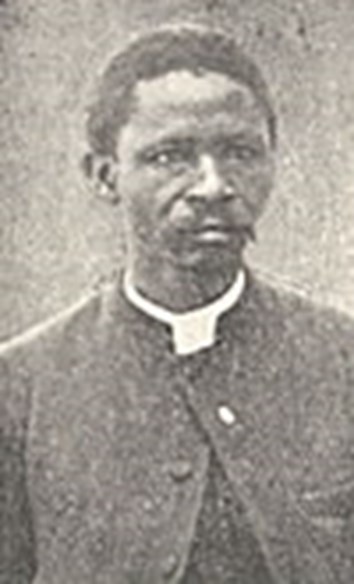

In the following 25 minutes, the troops gathered on deck, and what followed has become famous in South Africa. The battalion’s chaplain, the Reverend Isaac Wauchope addressed the men:

Be quite and calm, my countrymen, for what is taking place is exactly what you came to do. You are going to die, but that is what you came to do. Brothers, we are drilling the death drill. I, a Xhosa, say you are my brothers. Zulus, Swazis, Pondos, Basothos and all others, let us die like warriors. We are the sons of Africa. Raise your war cries my brothers, for though they made us leave our assegais back in the kraals, our voices are left with our bodies.’

Above: Sometimes referred to as Rev Isaac Wauchope, and sometimes as Rev Isaac Dyobha, legend has it that he addressed the men on the sinking ship.

Of the 611 South Africans who lost their lives, only 14 have known graves (the majority being buried in Portsmouth (Milton) Cemetery); the 597 with no known graves are commemorated on the Hollybrook Memorial, in Southampton.

Article by David Tattersfield

Read More:

Two men with five names: The Curious Case of Cornelius Costello