Zeppelins Over Norfolk

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Zeppelins Over Norfolk

The First World War was a conflict of many firsts. While the Great War saw the debut of mass public recruitment as well as the implementation of tank warfare, it was also the first time heavier-than-air flying machines had been used in a military offensive. As German airships attacked the east coast of Britain in January 1915, it was civilian targets that bore the brunt of some of the first air raids.

With the bombardment of Hartlepool, Scarborough and Whitby by warships of the German Navy’s High Seas Fleet, war had already come to the civilian population a few weeks earlier, on 16 December 1914. While the attack caused minor damage and a small number of fatalities in Scarborough and Whitby, over 100 civilians died in Hartlepool. Although the damage was confined to a limited geographic area, the bombardment succeeded in giving a temporary boost to Britain’s flagging recruitment campaign.

Above: Recruitment posters often referred to the bombardment of Scarborough.

But just five weeks after the attack on these east coast communities, a new dimension of warfare on the home front began. In January 1915, the first civilian fatalities were incurred through the use of enemy air power.

The use of flying machines was not new. Balloons had been used to transport letters out of Paris during the Franco-Prussian War in 1870, and Field Marshal Kitchener had been aloft as a young officer in the same conflict to watch the actions of the French Army.

Although the invention of aeroplanes had brought about opportunities for the military, Germany continued to persevere with older ‘lighter than air’ technology, using airships extensively. Many, but not all of these airships were built by a company founded by Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin, whose name is now associated with all of these aircraft.

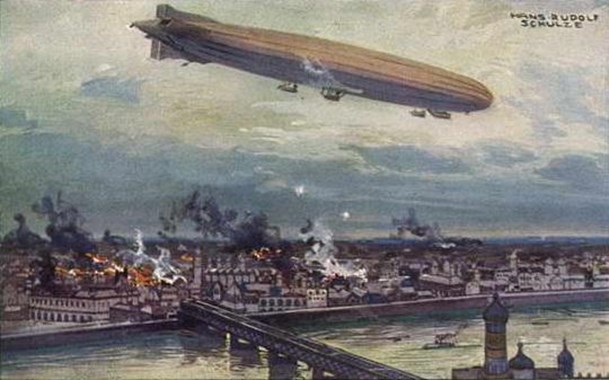

Above: German airship SL2 bombing Warsaw in 1914.

By January 1915, the First World War was a little over five months old, but already trench lines had been formed and alternative ways of attacking the enemy were being considered. Against this background, a raid on the port of Hull and installations on the Humber estuary was authorised by the Kaiser. It is likely that Hull was selected because the town was accessible across the North Sea from the main Zeppelin base near Cuxhaven (which had been attacked by R.N.A.S. Seaplanes on Christmas Day 1914 in a pre-emptive strike against the German Zeppelin sheds).

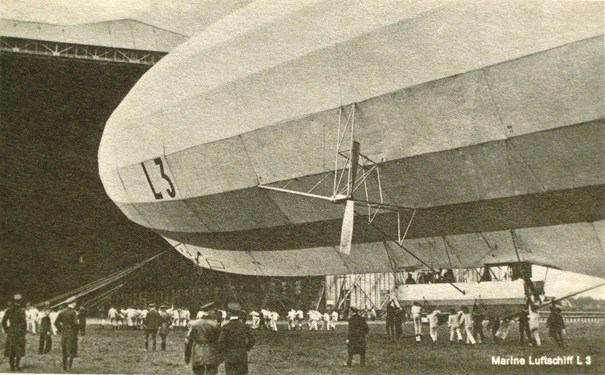

If the Christmas Day attack was intended to prevent German airships attacking the UK, it failed. On 19 January a raid by three German airships was launched. One of these airships, the L6, took off from Nordholz (near Cuxhaven) with the intention of bombing targets in the Thames Estuary. Due to bad weather this attack was aborted. However, two more airships, the L3 and L4, took off from Fuhlsbüttel (near Hamburg) at 11am and headed out to sea. With 14 or 15 crew members on board each aircraft, both were loaded with enough fuel to remain airborne for 30 hours (their maximum was range was over 1300 miles). They were each armed with eight 50kg high-explosive and 25 incendiary bombs. The intention was for them to cross the North Sea during daylight hours and then, at nightfall, make the attack on Hull.

Above: the L3.

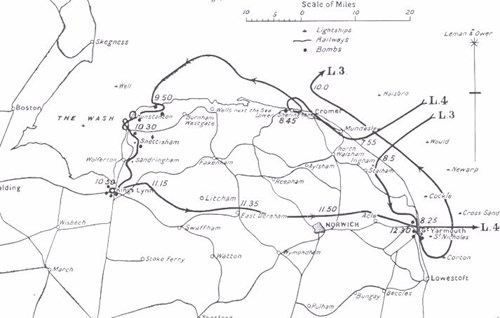

Approaching the UK, an increasing wind from the north meant that rather than flying up the Humber Estuary, the two airships crossed the coast of Norfolk between Cromer and Great Yarmouth at about 8.30pm. At this point they parted company.

Airship L4 (commanded by Kapitänleutnant Count Magnus von Platen-Hallermund) continued a westerly course and headed over Cromer before dropping a bomb on the seaside resort of Sheringham. This bomb, which fell on Jordan’s Yard, Wyndham Street (now Whitehall Yard) at 8.30pm, was the first to be dropped by air on British soil. Having failed to explode, a local resident picked it up and put it in a bucket.

A few minutes later, a second bomb was dropped in Sheringham; although this did explode, it caused no damage.

Plaque at Whitehall Yard, Sheringham.

The time was now 8.45pm, and von Platen-Hallermund (who likely believed he had bombed a town on the southern shore of the Humber estuary) turned out to sea in a vain attempt to locate Hull (which is on the northern shore of the Humber).

Above: route of the two Zeppelins

While the L4 was causing havoc at Sheringham, airship L3, commanded by Kapitänleutnant Johann Fritz, after crossing the coast, had turned south and headed towards Great Yarmouth.

On its way towards the town, the L3 dropped a number of flares and incendiary bombs. The first three bombs fell either in fields or did minimal damage, but the fourth bomb landed in the St Peter’s Plain area.

Above: “Mr Ellis wounded by a bomb and his ruined house at Lancaster Corner, St Peters Plain” from a postcard

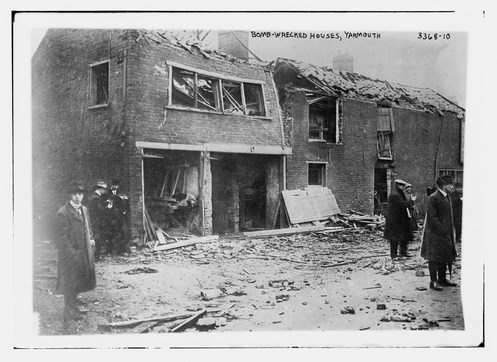

Above: Homes in Great Yarmouth damaged by bombs dropped by the German Zeppelin L3 on 19 January, 1915.

Numerous properties suffered blast damage and some buildings were so badly damaged that they were later demolished. But this bomb was significant because it caused the first ever British civilian casualties of an air raid.

Local shoemaker Samuel Smith, 53, was killed along with 72 year-old Martha Taylor. Two other civilians were also injured as a result of the attack.

Martha Taylor and Samuel Smith.

Further bombs fell on Great Yarmouth, some failed to explode, although one – which fell behind the Fish Wharf – damaged properties and burst a water main. The final bomb, according to accounts of the raid, fell near the town’s racecourse; this killed a dog and damaged a fence.

The attack on Great Yarmouth lasted little more than ten minutes, and well before 9pm the air raid was over and L3 turned out to sea to commence the return flight to its base in Germany.

Above: Kapitänleutnant zur See Freiherr [Baron]Treusch von Buttlar-Bradenfels. He was one of the officers on board the L3. Around his neck is the Pour le Mérite (Prussia’s highest order of gallantry) which he received in 1918.

Meanwhile the L4 was some miles to the northwest, and had failed to locate Hull. Turning back towards the shoreline, and by now hopelessly lost, von Platen-Hallermund brought the L4 down to low altitude. He re-crossed the coast at about 9.50pm near the village of Thornham, which resulted in him nearly colliding with a village school, and headed south. Bombs were dropped on the village church at Snettisham, where a meeting had just finished. This action blew out windows in the church but caused no casualties. The airship continued southwards, past the King’s estate at Sandringham and headed towards King’s Lynn, where a number of bombs were dropped causing a great deal of damage.

Above: Painting “Air raid on Snettisham Church by Zeppelin L4, 19th January 1915” by Ben Mullarkey

Above: Soldiers of the Territorial Forces clear up the debris following an air raid on King's Lynn. Behind them, the damaged roofs of several houses can be seen. Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, Q 53589

One bomb landed in Bentinck Street, resulting in the death of 26 year-old Alice Gazley.

Above: The remains of houses in Bentinck Street, King's Lynn, destroyed by bombs dropped by Zeppelin L4. Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum, Q53591

Alice had been widowed less than three months earlier, when her husband Percy was killed whilst serving with the Rifle Brigade in October 1914. Percy Gazley is commemorated on the Ploegsteert Memorial to the Missing.

Alice Gazley with her late husband, Percy.

Also killed in this attack was 14 year-old Percy Goate. In an inquest report, Percy’s mother said: “We were all upstairs in bed when I heard a buzzing noise. My husband put out the lamp and I saw a bomb drop through the skylight and strike the pillow where Percy was lying….I tried to wake him but he was dead. Then the house fell in. I don't remember any more.”

Percy Goate (photo above) and Alice Gazley are buried in adjacent graves in Hardwick Road Cemetery, King’s Lynn.

After dropping bombs on King’s Lynn, L4 turned east and (ignoring the large city of Norwich) headed towards the coast, coincidentally flying over Great Yarmouth on its way.

Leutnant zur See Kruse, who was one of the officers on L4.

Reaction in the Press

Reporting the incident the following morning, The Times speculated:

It was plain that the source of the disturbance was aircraft, though precisely of what kind could only be conjectured. The opinion is generally held that it was a dirigible, for what appeared to be searchlights were seen at a great altitude. Others, however, say that the lights were not the beams of a searchlight, but the flash of something resembling a magnesium flare.

—The Times Wednesday, 20 January 1915; p.8

Further news was published about the raid in the following days; here the reporter describes one of the unexploded bombs:

The upper part, for all the world like the "cone" to be found in every art classroom, is made of thin metal and packed with a resinous substance which, after experiment on a very small scale in an ordinary firegrate, I found to be highly inflammable.

—The Times Thursday, 21 January 1915; p.9

As can be seen from the image below, the novelty of finding these bombs clearly outweighed the perceived risks. This image is possibly the third bomb to have been dropped in Great Yarmouth, which was reported as having been “recovered by reservists and later defused”.

The attacks by airships continued for most of the war. A total of 52 raids by Zeppelin and other airships were carried out on the UK, although by 1917 these attacks were becoming less effective. Only six raids took place in 1917, and only four in 1918, the last taking place in August 1918. The casualties were tiny compared to those incurred in the Second World War, killing less than 600 civilians (with a further 1300 or so injured). Other German bombing raids – for instance, those carried out by Gotha bombers – caused further death and destruction. It has been established that a total of 84 German airships dropped 5000 bombs on the UK, but the cost to the Germans was high, with about 30 airships being lost, either in combat or as a result of accidents or weather conditions.

Although these airship raids may have caused localised panic, the effect on Britain’s war industries was negligible. While they may have slightly interrupted war production in isolated areas, the most significant outcome of these raids was to cause a great deal of public anger.

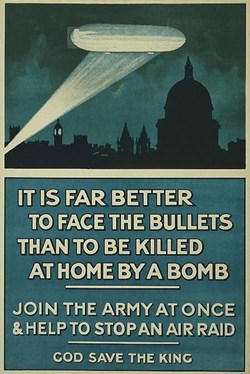

Above left: “The End of the Baby-Killer”, a 1916 poster.

Above right: A 1915 recruitment poster.

Further reading:

There is a rich set of resources on the WFA web site detailing Zeppelin air raids

The Enemy Above: British Reactions to German Zeppelin Raids in the Great War by Frank A Blazich

The Bombing of London by Ian Castle

The First Air Raid: Great Yarmouth by Bob Wyatt

Rex Warneford and the downing of LZ37 by David Tattersfield