Rex Warneford and the downing of LZ37

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Rex Warneford and the downing of LZ37

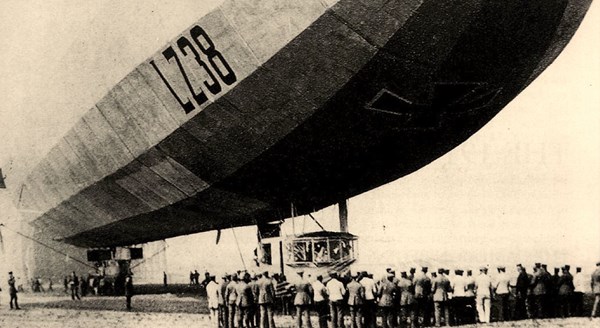

Zeppelin raids on London had started as early as January 1915 when towns in North Norfolk came under attack. Although this first raid was misdirected and caused minimal damage the fact that an attack had been made encouraged the German Kaiser to authorise further raids. For various reasons many of these attempts in early 1915 failed, and it was not until the end of April, when a more advanced Zeppelin came into service that bombs were again dropped. These raids in the Spring of 1915 were carried out by Zeppelin LZ38 over Ipswich (29/30 April), Southend (9/10 May) and Dover and Ramsgate (16/17 May).

Above: Zeppelin LZ38 preparing to take off from its base.

In response to these raids, Number 1 Squadron of the Royal Naval Air Service was stationed at Dunkirk and nearby Furnes (now Veurne) to try to intercept the Zeppelins on their return to their bases at Evere (near Brussels) in German-occupied Belgium.

Above: Personnel of No 1 Squadron RNAS in late 1914

During the third of these raids, a number of RNAS aircraft managed - against all the odds - to locate the Zeppelin and attack it. One of the RNAS pilots was Flight Sub-Lieutenant Warneford who flew a Nieuport two-seater, with Leading Mechanic GE Meddis as observer.

Above: Sub-Lieutenant Warneford

When they found the airship off Ostend at 5,000ft, Meddis opened fire from below the Zeppelin, however Warneford was unable to climb higher due to the load on board, which included hand grenades and a rifle.

Squadron Commander Spencer Grey, also flying a Nieuport, was the next pilot to attack and he fired his Lewis gun at the rear gondola despite being subjected to heavy fire from the two machine guns in each gondola.

Above: A 1917 watercolour by Felix Schwormstädt (1870-1938). "In the rear engine gondola of a Zeppelin airship during the flight through enemy airspace after a successful attack on England".

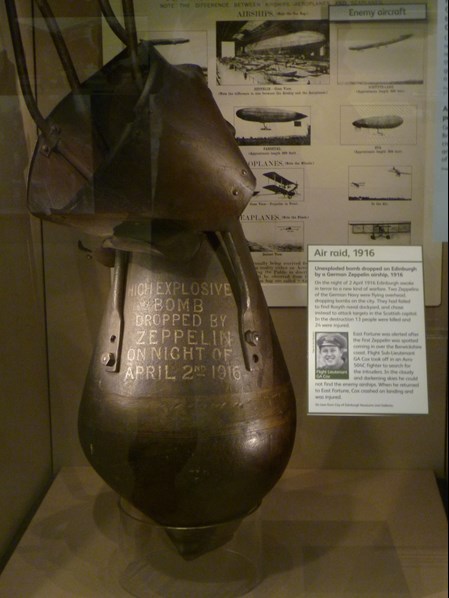

Although damaged, LZ38 was repaired and was able to make the first Zeppelin attack on London on 31 May. One hundred and twenty high explosive and incendiary bombs were dropped on Stoke Newington and Dalston. Also hit were Hoxton, Whitechapel and Leytonstone.

Above: An unexploded bomb dropped from a Zeppelin in 1916.

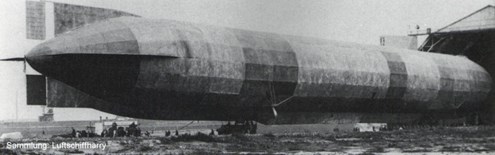

A week later, on 6 June, there was another attack on London. The RNAS base was alerted that three Zeppelins had been spotted. One of these was LZ37. Almost identical in proportion to LZ38, the airship was 536 feet long and had a capacity of about 1 million cubic feet for the hydrogen that kept it aloft.

Above LZ37 - Image courtesy of www. luftfahrtarchiv-koeln.de

Some accounts suggest LZ37 was one of the raiders, others that it was on a routine test flight with specialists rather than an offensive flight. Whatever the circumstances of the flight of LZ37, the RNAS pilots had been alerted to the presence of the Zeppelins. This danger would no doubt have been known to the Zeppelin's commander, Oberleutnant von der Haegen and his crew. However, no Zeppelin had yet been brought down by an aircraft, and with all its defensive armament, the crews of these massive airships no doubt felt invulnerable.

Reginald Alexander John Warneford

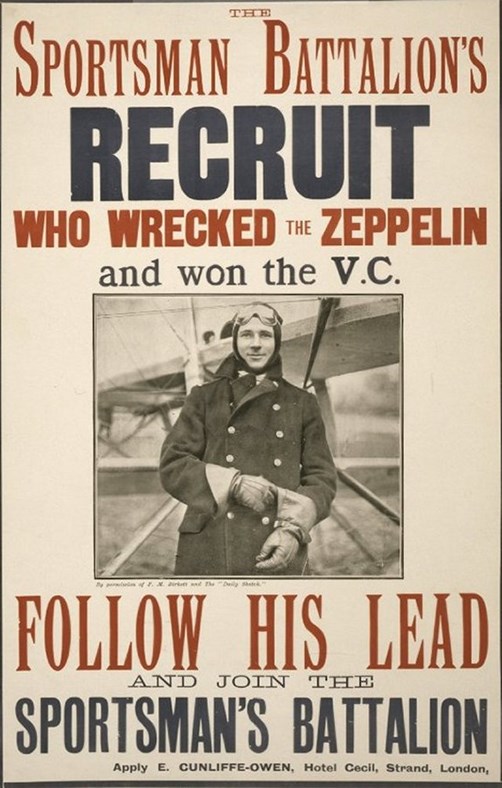

'Rex' Warneford was born in India in 1891. After leaving school he joined the Merchant Navy. When war broke out he returned to England and initially joined the Sporstman's Battalion (the 23rd Royal Fusiliers) but either because he did not fit in, or because he wanted to see action sooner, he transferred to the Royal Naval Air Service and quickly obtained his pilot's licence in February 1915.

Warneford's flying instructor later recorded:

"Warneford was in fact a born aviator. He had mastered the intricacies of flight with amazing swiftness, and, as he was completely without fear, my only difficulty was to check his over-confidence. The [flying centre] commander was so impressed by Warneford's brilliant flying that he made the remark: 'This youngster will either do big things or kill himself.' "

Warneford in the Illustrated London News, 12 June 1915

Posted to Number 1 Squadron, RNAS, Warneford was recognised as an aggressive pilot and, as recounted above, attacked a Zeppelin on 17 May 1915. No doubt he hoped to have more success in when, at 1am on 7 June several aircraft were ordered into the air when news of the Zeppelins came through.

Two pilots set off from Dunkirk to bomb the airship sheds at Evere, whilst Reginald Warneford was sent up on a patrol to see if he could intercept the raiders. In order to reduce weight in his aircraft, he flew alone without an observer. His aeroplane, a Morane Parasol type 'L', (numbered 3253) was armed with six 20lb bombs.

Above: A Morane Parasol Type 'L' (captured by the Germans and given German markings)

Whilst over Dixmude, Rex spotted an airship that appeared to be a little to the North, near Ostend. He aimed his Morane Parasol towards the Zeppelin and eventually caught up with the raider forty five minutes later, near Bruges. The crew had been keeping a sharp look out and Warneford was spotted.

Above: A 1917 watercolour by Felix Schwormstädt (1870-1938).

The resulting defensive fire was enough to prevent Rex making an initial attack. Despite the Zeppelin's lack of manoeuvrability, the commander, Oberleutnant von der Haegen turned the airship to attack the tiny Morane Parasol.

Above: Oberleutnant von der Haegen. Image courtesy of www. luftfahrtarchiv-koeln.de

Rex turned away to make the Germans believe he had given up the attack, but instead climbed to a height of 11,000 feet in order to attack from above.

Above: Warneford making his attack on LZ37

Gliding down in a silent approach, Warneford flew above the vast Zeppelin and pulled the bomb release handle - one by one the small bombs fell away - but had he hit the target, and would the bombs have any effect? He did not have to wait more than a few seconds to find out.

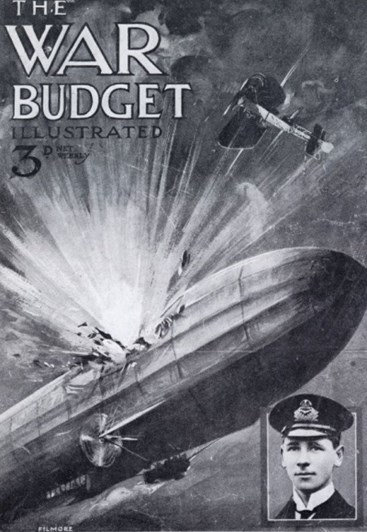

Above: The front cover of a contemporary magazine re-created the event.

The hydrogen inside the Zeppelin exploded and sent his fragile aircraft upside down and temporarily out of control.

Zeppelin LZ37 crashes to earth

Incredibly there is an account of what happened to the Zeppelin from one its crew. Alfred Muller wrote the following account:

I rushed from the wheel to the gondola door; I was overcome by terror. What had happened? A crackling. rattling sound. otherwise then, was dead silence in the gondola.

Above: Some of the crew of LZ37. Muller is second from the left on the back row. (Image courtesy of Michael O'Connor: Airfields and Airmen of the Channel Coast)

The commanding officer was slumped over the side: the first officer lay over the chart table: the (others) had fallen to the floor of the gondola. Nobody moved. Were they unconscious? I just stood there. What had happened? A shudder of horror. A quick look at the rear gondola brought a new terror. Almighty God! The ship was on fire!....

...An impact brought me round again. I was still alive. Had I dreamed it all? Or had a miracle happened? How had I got here? Was I still falling? No, I was on a bed, and a nun was standing by me. I stared at her wide-eyed. Above us were the flames crackling loudly, and a beam fell in.

As unlikely as it sounds, Muller had somehow survived a fall of several thousand feet. His Zeppelin had crashed into a convent in Ghent, killing one nun and injuring others. Muller however had landed in a bed - the only one of the crew to survive the explosion and crash.

Meanwhile, Warneford had major problems. Despite managing to bring his aircraft under control, the engine cut out and he found himself coming down in German-held territory.

With amazing skill, Rex brought his Morane down in a field and landed safely. Inspecting the engine, he discovered that his fuel line had been broken, no doubt due to the violent way the aircraft had been buffeted when the Zeppelin exploded. Carrying out a repair to the fuel line (using a cigarette holder) Warneford was able, half an hour later, to restart the engine. The process of taking off was usually a three man operation, but swinging the propeller himself then scrambling aboard before it ran away from him, he was able to get into the sky. But he still had no idea where he was in relation to the front lines. He flew on a westerly heading and eventually landed on the beach at Cap Griz Nez at Calais. Here, he was able to obtain fuel from a nearby French unit and make his way back to his base.

His report, to his commanding officer is understated:

Wing Commander Longmore.

Sir,

I have the honour to report as follows: I left Furnes at 1:00 A.M. on June the 7th on Moräne No. 3253 under orders to proceed to look for Zeppelins and attack the Berchem Ste. Agathe Airship Shed with six 20-lb.bombs.

On arriving at Dixmude at 1:05 A.M. I observed a Zeppelin apparently over Ostend and proceeded in chase of the same. I arrived at close quarters a few miles past Bruges at 1:50 A.M. and the Airship opened heavy maxim fire, so I retreated to gain height and the Airship turned and followed me.

At 2:15 he seemed to stop firing and at 2:25 A.M. I came behind, but well above the Zeppelin; height then 11,000 feet, and switched off my engine to descend on top of him. When close above him, at 7000 feet I dropped my bombs, and, whilst releasing the last, there was an explosion which lifted my machine and turned it over. The aeroplane was out of control for a short period, but went into a nose dive, and the control was gained.

I then saw that the Zeppelin was on the ground in flames and also that there were pieces of something burning in the air all the way down.

The joint on my petrol pipe and pump from the back tank was broken, and at about 2:40 A.M. I was forced to land and repair my pump.

I landed at the back of a forest close to a farmhouse; the district is unknown on account of the fog and the continuous changing of course.

I made preparations to set the machine on fire but apparently was not observed, so was enabled to effect a repair, and continued at 3:15 A.M. in a south-westerly direction after considerable difficulty in starting my engine single-handed.

I tried several times to find my whereabouts by descending through the clouds, but was unable to do so. So eventually I landed and found out that it was at Cape Gris-Nez, and took in some petrol. When the weather cleared I was able to proceed and arrived at the aerodrome about 10:30 A.M. As far as could be seen the colour of the airship was green on top and yellow below and there was no machine or gun platform on top.

I have the honour to be,

Sir,

Your obedient servant,

(signed) R. A. J. Warneford,

Flt. Sub-Lieutenant.

Victoria Cross

Warneford's success was recognised as being a fantastic achievement and he was told, by telegram, that he had been awarded a Victoria Cross as well as the Legion d'Honneur from the French Government. Just days later, on 12 June Warneford travelled to Paris to receive his French decoration, this was reported in the Daily Mail two days later, reinforcing his fame with the British public.

The last photo of Warneford, seen wearing the Legion d'Honnuer

Five days after the ceremony, Warneford was back in Paris to collect a new aircraft. After a brief test flight, Rex was ready to set off. Before he did so, he agreed to give a joyride to an American journalist, Henry Needham. After climbing several hundred feet, the wing came away from the aircraft and both occupants were thrown out. Needham was killed immediately and Warneford died whilst being taken to hospital.

Click here for a newspaper report of the crash (which erroneously describes him as a Canadian).

The wreckage of the aircraft Warneford was flying on 17 June, from the Illustrated London News dated 26 June 1915.

Memorials and Graves

The site of the crash of Zeppelin LZ37 is now marked by a modest plaque on a wall of Sint Jans College in the suburbs of Ghent (image below).

The crew of the Zeppelin were buried in Ghent in the 'Western Cemetery' (the CWGC detail this as the Gent City Cemetery) where there still stands a large and imposing monument to the crew of the Zeppelin.

Above: The memorial to the Zeppelin crew in Ghent.

Meanwhile, Warneford's body was (unusually) brought back to the UK for burial. Several thousand people turned up at the Brompton Cemetery in London for the service.

Warneford's cortege, from the Illustrated London News 26 June 1915.

Warneford's (non standard) headstone in Brompton Cemetery.

Memorial plaque inside the Church of St Michael & All Angels, Highworth

Not surprisingly, Warneford's fame - and the manner of his demise - led the authorities to use him to help boost recruitment, with his old battalion being quick to associate itself with him.

Recruitment poster for the Sportsman's Battalion.

Warneford's Victoria Cross (with the blue ribbon - this for recipients who were in the Royal Navy) is held at the Fleet Air Arm Museum in Yeovilton.

Above: Warneford's medal set.

Other early RNAS pilots

Anyone interested in visiting the graves in France and Belgium of these early RNAS pilots may wish to visit the following

- Calais Southern Cemetery, where Flight Lieutenant Herbert Wanklyn is buried.

- Ramscappelle Road Military Cemetery, where Flight Lieutenant David Keith-Johnston is buried

- Zuydcoote Military Cemetery is the last resting place of Flight Lieutenant John Bone, who originated from Canada.

Further Reading

An excellent account of Warenford is available in Airfields and Airmen of the Channel Coast (Battleground Europe) by Michael O'Connor

A booklet has been produced about Rex Warneford by the Wiltshire Branch of the WFA (priced £4 including UK postage, other areas may involve slightly higher charges).

Details of how to acquire this can be obtained by contacting the WFA's Wiltshire Branch Chairman Paul Cobb

First Through the Clouds – the Autobiography of a Box–Kite Pioneer By Frederick Merriam is reviewed on the WFA's web site

Articles on WFA web site

There is a rich set of resources on the WFA web site detailing Zeppelin air raids

The Enemy Above: British Reactions to German Zeppelin Raids in the Great War by Frank A Blazich

The Bombing of London by Ian Castle

The First Air Raid: Great Yarmouth by Bob Wyatt

The End of The Zeppelins (this item first appeared in Stand To! No. 31 in Spring 1991).

Zeppelins over Norfolk by David Tattersfield

Further Media

The BBC featured the story of Warneford in a local broadcast and also interviewed the chairman of the WFA's Wiltshire branch, Paul Cobb. This footage (5 minutes) is available on youtube

A BBC pod cast (7 minutes) featuring Lt Commander Chris Gotke of the Royal Navy Historic Flight talking about Warneford's heroics is available from the BBC

A video showing a replica of Warenford's Morane-Saulniew Type L being prepared for take-off is available on youtube

And finally, Warneford's funeral was so newsworthy that cinematographers were present, and the footage of the event is available on youtube.

Article by David Tattersfield