Boy Soldiers of the Great War Revisited by Richard van Emden

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Boy Soldiers of the Great War Revisited by Richard van Emden

[This wonderful article first appeared in the April 2022 edition of Stand To! It is shared here by way of example of the quality of articles members enjoy in every edition of our journal].

Shortly before my father died in 2002, he had a book published that he had been working on since the late 1970s (it was on the Old French epic The Song of Roland, an 11th century poem loosely based on a battle fought in 978). He had written the book in French (Dad was trilingual) but then, unexpectedly, he was told by the commissioning editor to write it in English. He ditched the French, wrote the English, only to be told to write it in French after all; he had not backed up the first version. To cut a long story short, it took twenty odd years to complete. He was a pure academic, I am not, and I recall being determined that if nothing else, I would not leave too many ‘intended–to–be–written’ books ‘out there’ before I called it a day: Dad left seven and I guess based on the above, he may have needed another 140 years to complete his work.

I am a competent writer and I am a decent researcher but, if I am to blow my own trumpet for a moment, then I would say that my best asset is possessing a nose for a good story, one that I feel is, taking the Great War as the context, a bit ‘different’, a story that has rarely and sometimes never been touched upon by fellow historians.

Whenever I have spoken to friends about the Great War, friends who may know little about the period, they assume that every subject, every aspect of the 1914–18 War must have been written about by now, every angle covered by someone else, no literary stone left unturned and so forth. They are astonished to discover that, to my mind, there are nearly as many books to be written on the endlessly fascinating subject as have been completed and published; in other words, thousands of new and enlightening stories are still out there just waiting for an author.

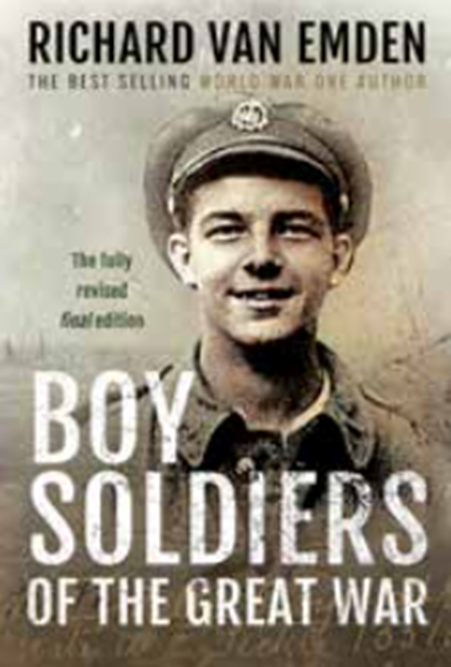

I am not particularly interested in generals, nor weaponry, not even battlefield tactics to any great extent. I am not that bothered about some of the minutiae of war that others become fascinated by, including cap badges, shell fuses and military kit, to name just three. Each to their own, I believe. My interest is in the human condition during war, a fascination with what people can endure in the nigh certain knowledge that I would have run a mile (and been shot for cowardice). Which is why I am highly curious about those who chose to take that test, naively or not, hence my book Boy Soldiers of the Great War. Here we have lads aged as young as 13 diving headlong into the hardest, most exacting crucible of conflict imaginable and surviving – even occasionally flourishing. How on earth did they manage?

I love the Great War as a subject. I am often asked how it all started for me. In 1984 I saw a documentary on the war, presumably commemorating the 70th anniversary of its outbreak, and I realised I knew nothing about it. That Christmas I asked my parents for a celebrated memoir. Robert Graves’ Goodbye to All That appeared under the tree and within days I was hooked, never to return to normal life. A visit to the Chelsea Pensioners’ home and I met my first veteran, named Ernie, a soldier of Passchendaele where he fought aged 18. He was underage, though by the standards of the day, not by much. I knew then that I should try and speak to as many surviving veterans as I could. When I went to the Somme in 1986, for the 70th anniversary of the battle, I met 20 veterans, a third of whom turned out to have been underage when they fought on the Western Front.

That second visit to France confirmed a second love. I adore walking the Somme battlefields and I later became entranced by Gallipoli (introduced to me by the great Peter Hart). But I would not write a book about either campaign unless I could bring something entirely new to the table, hence my passion for soldiers’ own photographs and the series of books I have written (or co–written) using them.

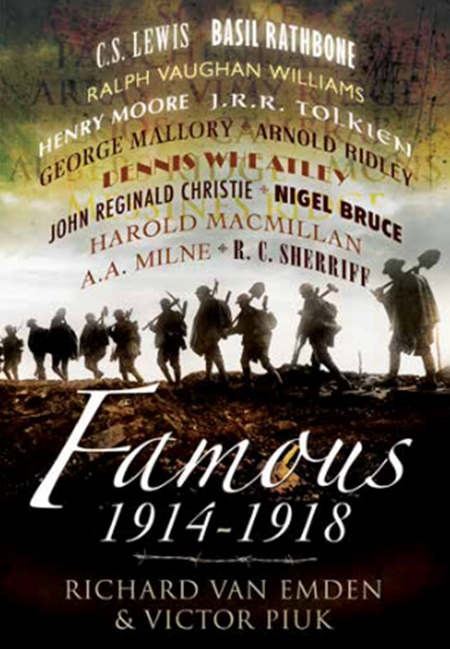

Back to my nose, and my desire to write books with a distinctive perspective. So, for example, fusing the home front with the Western Front, and not to see them in isolation, was the key motivation for writing The Quick and the Dead. I wondered about animals and in particular wildlife in and around the trenches when I wrote Tommy’s Ark. And the stories of those who served in the war and went on to become household names appear in my co–authored book Famous, 1914–1918.

Boy Soldiers of the Great War was a story that began after walking the battlefields and being struck by the number of young, sometimes very young, lads who were killed in the war, and whose ages were carved on gravestones. I was once told by the late Grace Acott, sister of the legendary Rose Coombs, that Rose had mused over the story of the underage lads who went to war and thought it was a tale worth telling... I am eternally glad Rose chose not to pursue it. I am equally glad that no one else did either, a fact that rather amazed me when I came to roughing out a coherent storyline. Most writers can turn to other books to give them an outline, some basic facts about the history upon which they are about to embark. With Boy Soldiers, there was nothing, and I do mean NOTHING. There were memoirs by lads who served overseas and underage, such as George Coppard’s With a Machine Gun to Cambrai, but he did not dwell unduly on the story of his youth, and I could only take scraps from what he chose to recall. Other memoirs would give me more detail; John Gowland’s brilliant War is Like That for example, but mostly I relied on the interviews I had conducted with Great War soldiers in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

I had interviewed men like Frank Lindley who fought aged 16 on the Somme, in particular on that first day when he was wounded. I spoke to Norman Skelton, ex Royal Engineers about his service but I had not yet truly registered the importance of their youth or focused on themes that identified them as underage, such as the myriad ways they chose to lie on enlistment.

My first book, published in 1996, was a memoir of a great friend of mine, Benjamin Clouting. He had served throughout the war with the 4th (Royal Irish) Dragoon Guards, most notably in August 1914 when he held the horse of Drummer Thomas, the man credited with firing the first short of the BEF on continental Europe since Waterloo. Ben was 16 at the time, the youngest soldier in the Regiment, and we spoke at length about how he had managed to game the system and get into the Regiment to serve overseas. But even then, I missed some of the stories of his youth that I would have asked had he been alive a decade later.

Where does one start to build a story that no one has explored before? Well, go and see if the issue ever raised its head in Parliament. Hansard was the obvious primary source, and not knowing whether the issue of underage soldiering was ever discussed, I looked. I have a large lever arch file containing the best part of 300 pages I should think, each page a photocopy of a debate in the House of Commons on the very issue I was researching, heated debate after heated debate. There was one name in particular that kept cropping up, Sir Arthur Markham, who fought and fought again to stop the lads going overseas, particularly those of extreme youth. On the other side of the Dispatch Box stood his bête noire, the Under Secretary of State for War, Harold Tennant who, in presenting the Government line on this issue, was not averse to being economical with the truth.

I should stress that I had no intention of ever writing a ‘lambs led to the slaughter’ diatribe. All my instincts told me that the story was going to be much more nuanced and interesting than simply to lambast casually and lazily those in authority. I am not and have never been one of the ‘General bashers’, indeed over time I have grown more appreciative of what they achieved. That said, there was a story here that must have involved the army in some act of collective ‘blind–eye turning’ for so many lads to get across to France.

It was critically important that I tried to see the story through a 1914 perspective, not a 21st century one, to understand what motivated the boys to go and to appreciate what made recruiting sergeants allow them to enlist. We are all aware of the recruiting sergeant who, when a boy claimed to be 16, would tell him to go outside, walk round the block and re–enter the hall now magically aged 19. While some of those in charge of recruitment did line their pockets with bounties paid for each recruit, there was another story, namely most never believed these boys would ever be involved in actual fighting since the war would be won within the year. Rather, these undernourished, wheezy lads fresh out of iron foundries and coal pits, would flourish with fresh air and three square meals a day. With a bit of fun serving alongside their mates and daily exercise, these boys would put on two inches in no time; it was certainly the reason why so many parents permitted their sons’ recruitment in the first place. It was always with that awareness of alternative narratives that I researched each aspect of the story I could identify.

I always knew that this book may not appeal to all sections of the Great War community, some of whom might feel that focusing on such a story was by its very existence a surreptitious attack on the establishment of the day – that even calling a book Boy Soldiers of the Great War was an incitement to the so–called ‘bleeding–hearts brigade’ to pick up metaphorical mallets with which to bludgeon Haig and his ilk. I am also very conscious that the death of a 15 year old in the trenches, while his age pulls at our heartstrings, is no more and no less tragic than the death of a 30 year old father of four children: it is simply a different tragedy.

With this in mind, I was determined to be even–handed. My aim was to present the history in such a way as to leave the reader with the tools to make up their own mind as to the culpability or otherwise of the senior command and of politicians and parents, and not forgetting the boys themselves.

Back in the days when local newspapers were widely available and widely read, it was useful to place appeals for information, asking readers to get in touch with their stories of relatives who had served underage. Thirty years ago, it was possible to get well over 1,000 replies to a press mail–out and, even 20 years ago, I could expect replies numbering into the hundreds. Those days have gone, sadly. Within days of my 2003 appeal, I received many offers of primary material held in letters, memoirs and diaries, more than I could ever use.

Access to online records held by Ancestry proved to be incredibly helpful when researching letters written by proud, sometimes indignant or at times desperate families, letters that are attached to the pension files of underage soldiers. These missives gave an insight into contemporary parental concerns, whether it was about securing the release from the trenches of an errant son, or questioning why a son, once home, was kept in uniform and not discharged. Sometimes there were letters from boys pleading for insignia, such as the Silver War Badge, a badge worn on the right breast or jacket lapel that denoted honourable service at the front. The badge would help stop the ritual abuse of these lads meted out by civilians who assumed that these boys, most looking far older than their actual age, had never bothered to serve their country.

As the story developed, I knew I would have to make some assessment as to the numbers who served at home and overseas. I won’t bore you with the details but, in the first edition of the book, I came up with a figure of 250,000 underage soldiers. When my agent managed to secure a publishing contract with Headline, I knew this was a figure that would likely loom large in any press features, and I accepted that I would have to substantiate it. I will admit now that my figures were extrapolations based on examining the CWGC records. Back in the early 2000s it was not possible to simply put in an age, say 17, and count how many hits I got back. Back then it was a case of going through every name to see if there was an age attached. I am almost embarrassed to admit that I ran every possible combination through the online database beginning at AA (I guess Aaron would have been amongst the first returns) through to ZZ, of which there would be none. I printed off those whose ages were given as 17 or under and did a simple head count for those aged 18; the minimum requirement for overseas service was 19.

The high stack of pages was used to great effect when I pitched the idea for a documentary to Channel 4. The ruse was to go into a meeting between a commissioning editor and my then boss and ‘happen’ to casually present this stack of printed pages as proof, if proof were needed, that there was a great story here. I still recall the wide–eyed look of the editor as he flicked through printed page after printed page of named underage lads and the cemeteries in which they were buried or the memorials to the missing upon which their names were inscribed. I made sure many of the 15 and 16 year olds were near the top of the pile.

I digress. The statistics I produced were backed up with other evidence, but I always felt a little fragile on the stats, simply because I could not prove them enough to my own satisfaction. However, publishing deadlines were such that, while I had already spent an inordinate amount of time making my calculations, I simply could not spend more honing further what I had. The book was going to be published and I had to deliver. On the upside, I also felt that while my figures were to some extent speculative, they were also on the low side. There was something of the gut feeling about this, but when the updated edition came out in 2012, I was able to back up what I had written with more, I thought, compelling circumstantial evidence, though the figure remained the same.

It was only with the latest and last edition of the book that I revisited my stats, looking at the evidence in an entirely new way and coming up with a much higher figure than I originally proposed. The new figure, of 400,000, is based upon detailed research into the service of men who died aged 19 in 1916, 19 and 20 in 1917 and 19, 20 and 21 in 1918, looking at when these men actually went overseas. The figures for those serving overseas and underage in 1915 and 1916 are mind–boggling.

The latest and what is the last, updated edition of this book sharpens up much of what I said before, but it also adds many new stories and additional themes based on exhaustive research of the Ancestry database: I looked through thousands, probably tens of thousands of individuals to seek out these new stories. I cannot begin to describe what a monumental amount of work was undertaken on this edition but unless someone can turn up a 12 year old in the trenches and/or a 13 or 14 year old casualty, I will not be revisiting the story again, though I shall never be able to quite look away as and when I come across new material.

There is no doubt in my mind that having had three cracks of the whip this story has improved with each revision. I may have felt happy about the first edition back in 2006, but as with all these things a book can be improved. I always worked with the following mantra in my head: ‘the best that I could do in the time available’, and this has allowed me to hand over a book when perhaps the purist would have demanded more time, much to the publisher’s distress. That said, I would never hand over a book I was not happy with, and I have preyed upon the patience of several publishers over the years.

Had I produced only the first edition, I would be writing here about what angles I might have revisited, or what themes with hindsight I might have introduced. The second edition naturally upgraded the first, but the nine year hiatus between the second and the third editions has given me the chance to improve things as much as I can, to the point where I now feel the book is ‘done’. Interestingly, I have been able to revisit a couple of key stories. One, the death of Private Parr, considered the first casualty of the war, was introduced in the 2012 edition as a new story. I had been unaware that he was 17 when he died and so I knew I would have to include him. In the 2021 edition, I was able to take onboard persuasive research by historian Andrew Thornton, who proved, at least to my satisfaction, that Parr was killed on 23 August and therefore not the first to die, though he was amongst the first to fall, and he was certainly aged 17.

The other story concerns Private S Lewis, identified in The Mirror newspaper in September 1916 as being aged 12 when he enlisted and 13 on the Somme. No one since had identified Private S Lewis, not least because he was noted as having served with the East Surrey Regiment, which was not the unit with which he went overseas. On publication of the second edition, I noted the boy’s youth, and also in a subsequent newspaper article that I helped write for the Daily Mail. This article was spiked. Then, at the last moment, The Sunday People took it and this proved to be extraordinarily fortunate, for who should be a regular reader of The Sunday People but the son of Private S Lewis? Colin Lewis got in touch to tell me his father was Sidney Lewis of the Machine Gun Corps, and he had all the evidence to prove it. A blue plaque now features above the front door of the house in Tooting, London, that Sidney walked through in 1915 to enlist. So, information that appeared hopelessly beyond my reach in 2012 has now been researched in detail and written up in the 2021 edition.

In the last issue of this journal I read Gordon Corrigan’s fascinating essay on his book Mud, Blood and Poppycock, at least in part so as to get a feel for what I should write. I was interested in his primary and very laudable desire to move the dial on public attitudes towards the Great War and the all too prevalent view that the war was pointless, and the men incompetently led. The dial has certainly moved for me on these issues over the years. My book is very different from Gordon’s – clearly – but in one key aspect I wish to highlight: I did not seek to move any dial on the story of underage soldiering. That nose of mine had led me to what I have always believed was one of the great untold stories of the war and I am just thankful I made it to the starting post first.