Brothers in Arms: Three Died and Three Survived the First World War

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Brothers in Arms: Three Died and Three Survived the First World War

The First World War resulted in terrible suffering for many families, but the Willis family was among those that paid the highest of prices: six brothers went to war, but only three came home. Of the surviving siblings, one had lost a leg and the other two also left with recurring health problems.

The Willis family had travelled from Nottingham to Manchester in search of work in the late 18th century. After moving around various working-class areas to the north of the city, they finally settled in a three-up, two-down terrace in Moston, North Manchester.

Above: The family home at Elizabeth Street in Moston, North Manchester, is still standing.

It was from this family home that most of the boys left their mother Eliza to head for war, their father having already died some years earlier.

The first of the boys to sign up was Ernest, a 24-year-old labourer, who was placed with the Rifle Brigade (4th battalion). From his records it looks like he initially struggled with the discipline of Army life and was punished more than once for missing parade. He would, however, make up for these indiscretions when he reached the Front.

Above: Ernest pictured with one his brother’s children and Fred also seen in uniform, and his name on the Menin Gate memorial to the missing

Next to join was Fred, who was 32 and a hat block maker. Fred was single like Ernest and also served with the Rifle Brigade, but with the 9th battalion. Fred’s unit would go into action before Ernest’s at Hooge, Belgium, and on September 25, 1915 - just four months after first walking into the recruitment office - he was dead.

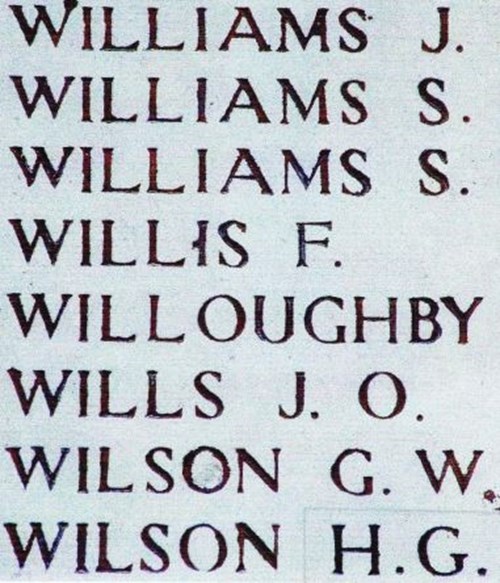

Fred’s body was never recovered from the battlefield, a spot on the Bellewaarde Ridge not far from where the Royal Engineers Memorial is now to be found, and is remembered on the Menin Gate memorial to the missing at Ypres.

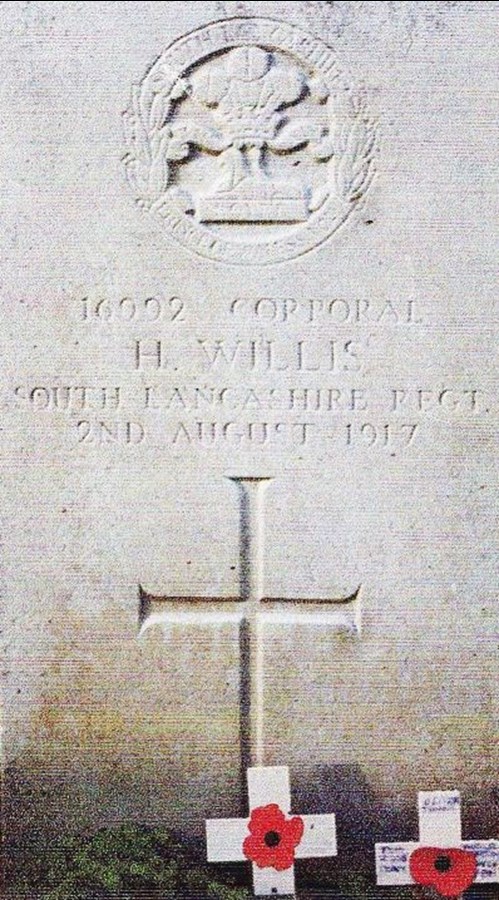

A month after Fred had signed up, the second youngest of the brothers, 19-year-old Harry, had enlisted with the South Lancs (2nd battalion). A fitter by trade, he left his fiancé and home in December 1915 and was soon in action at Arras before heading to the Battle of the Somme. A survivor of these battles, Harry found himself in Flanders next and was sheltering in a dug-out at Railway Wood on August 2,1917 when a German shell landed on top of it - killing Harry and 20 others and wounding a further 23.

Above: Harry with his fiancé prior to leaving for war and his headstone at Poelcapelle.

It turned out that Harry had been killed only a few hundred metres from where Fred had died two years earlier at Hooge, but unlike his older sibling his body was to be recovered and he is now buried in the Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery at Poelcappelle, Belgium.

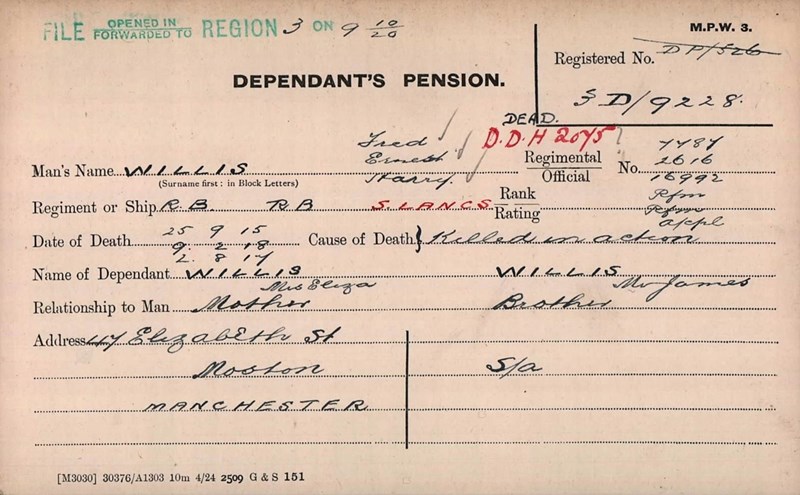

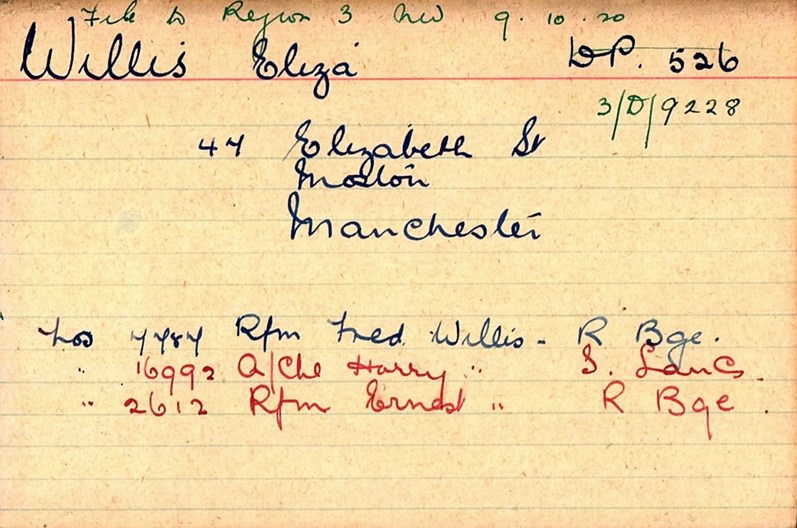

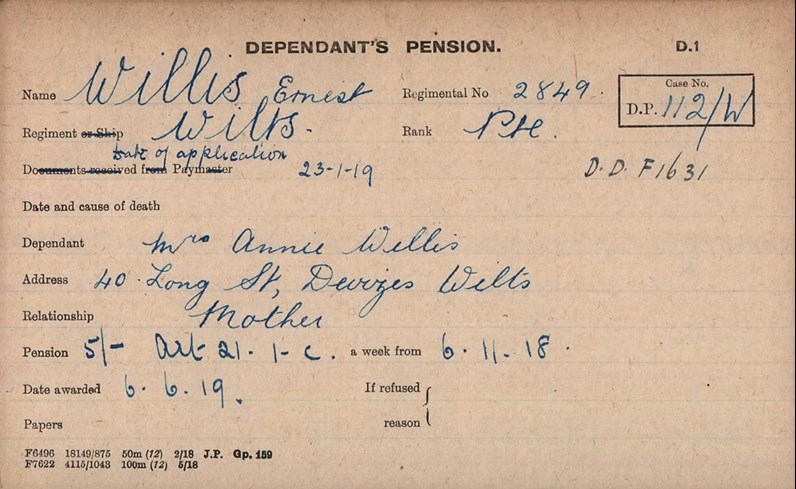

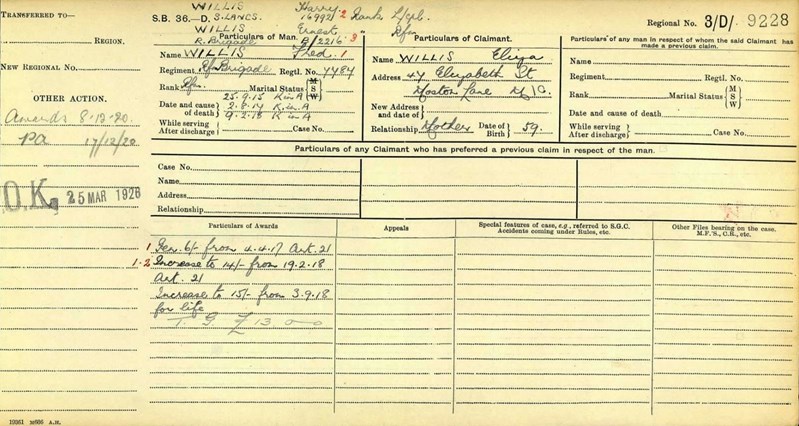

Above: Just a few of the pension records for the Willis brothers.

By this time the youngest brother, James William, had also enlisted. He had been just 17 when war broke out and working as a cotton dyer. James enlisted with the Manchester Regiment (7th ‘pals’ battalion) less than a year later, having lied about his age (his Army records show him as being 19 on enlistment). This enlistment came just few weeks after the death of the first of the brothers, Fred, which may well have influenced his decision.

There are gaps in James’s military record in which he clearly spent long periods away from duty, and he would see out the war with the Labour Corps. The explanation for these absences may well be linked to a rejected claim he made for a disability pension in the years after the war in which he said that he continued to suffer from deafness ‘caused by shock’.

Above: Photo of the youngsest brother James and (below) a photo of Thomas, who is seen with his wife Elizabeth and one of their children.

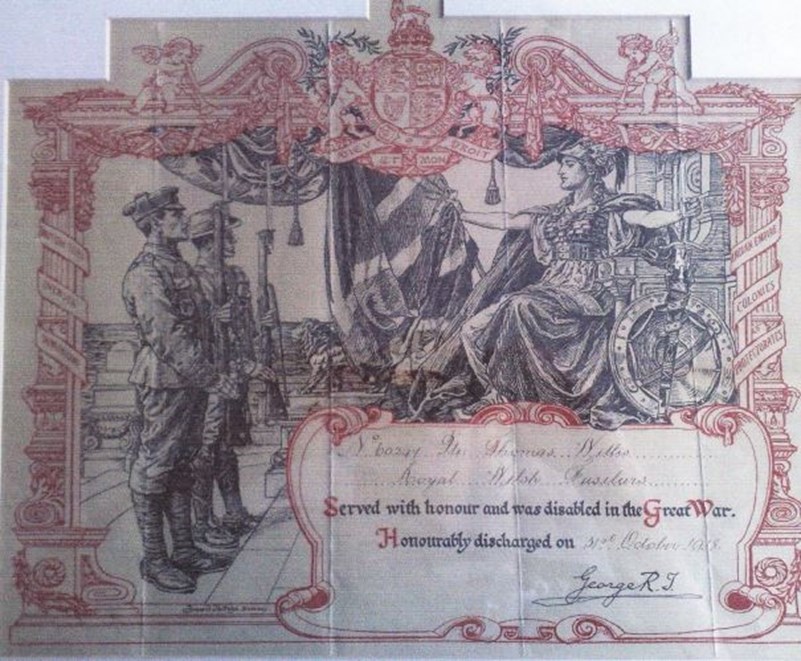

The fifth brother into uniform was Thomas, who had moved out of the family home a couple of years prior to the war. He had been 21 when he married his sweetheart Elizabeth on August 3, 1914 – the day before Britain went to war.

Thomas was an upholsterer and it is not clear if he was a conscript. Ultimately placed with the Royal Welch Fusiliers (10th battalion), he would go overseas in early 1917 and return home without one of his legs just a couple of months later.

The late Tom Willis, Thomas’s son and a former stalwart of the WFA Lancashire and Cheshire Branch, said that his father did not talk about the war often, but recalled him explaining that he had been laid out wounded for two days in the open at Monchy, Arras, in June 1917 before he was finally found by the stretcher bearers. As a result of the delay in treatment, gangrene set in and the wounded leg had to be amputated.

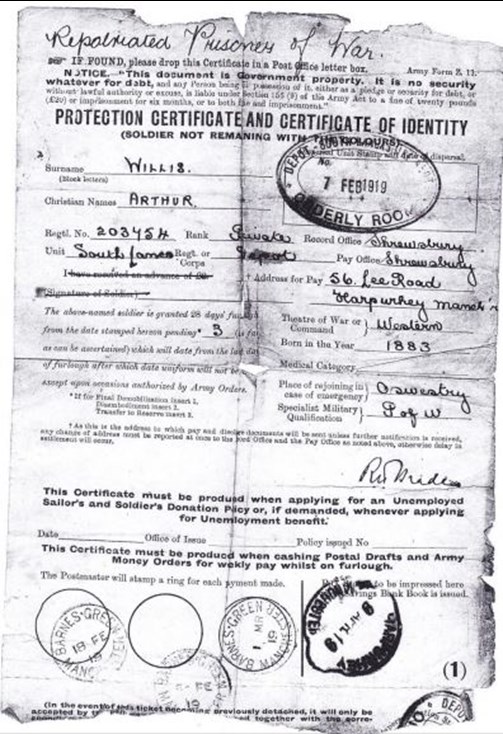

Above: Arthur’s repatriation document from 1919 and a picture of him in a PoW camp - he is the blurred figure on the front row to the side of the authoritarian gentleman at the front.

The last brother to go to the Western Front was Arthur, who was the oldest. He was 31 at the time of the war, married and working as a cabinet maker. It seems likely that Arthur didn’t get abroad until late 1916, or even 1917. He was serving with the South Lancs territorials (1/5th battalion) and taken prisoner during the Battle of Cambrai in November 1917 after “not a man returned” from his battalion when they were all-but surrounded with many already killed.

Among those who had also been involved at Cambrai, but escaped capture or worse, was the first of the brothers to sign up, Ernest. By this point he had been out fighting since July 1915 and survived many of the worst battles of the war, but his ‘luck’ was to run out in February 1918 when killed by German shelling on the outskirts of Ypres. He is buried in the Bedford House Cemetery, Belgium.

“It is hard to know what effect the loss of the three brothers had on the surviving three. Like many men who fought, they did not talk openly to us about it. My dad definitely didn’t,” explained Thomas’s son back in 2014.

Above: A scroll recording Thomas’s honourable discharge after he lost his leg and (below) a modern shot of Velu Wood, near to where he lay out on the battlefield for two days.

“Dad had moved back into what had been the family home in Moston after the war and would go on to have three daughters and a son to look after. I was born in 1935 and my mum died a year later. Dad, who was working as an upholsterer, just ‘got on’ with things. He never let his disability keep him from work and even refused free school dinners for us as he considered it a matter of pride and dignity to ‘provide for my own’. He died in 1951 and is buried in Moston Cemetery in North Manchester.”

Of the other two surviving brothers, Arthur returned home in February 1919 having suffered considerable as a prisoner of war. He had four children and lived a quiet life in Manchester.

James, who suffered from ‘shellshock’, was to marry and have a son but would move into a more semi-rural community in Lancashire.

Tom Willis would often say of his dad and uncles: “I remain proud of all of them.”

Article by Dr Martin Purdy