'We Too Were Soldiers' by Dr Vivien Newman

- Home

- World War I Articles

- 'We Too Were Soldiers' by Dr Vivien Newman

WAAC workers and Chief Ordnance Office Staff, Rouen 1917

‘We Too Were Soldiers’ 1

By Dr Vivien Newman

Viv Newman's long-standing interest in the Great War led, after many years teaching women's war poetry at A level, to a PhD thesis entitled Songs of Wartime Lives: Women's Poetry of the First World War (2004) University of Essex. The thesis examines women's war poetry as historical source material. Viv gratefully acknowledges the WFA's generous bursary which enabled her to visit a number of archives and re-discover a wealth of women's poetry.

Viv's grandfather, Major Arthur Scott-Turner RAMC, FRCP, FRCS, served as a surgeon on the Western Front from November 1914 to March 1919. Partly as a result of his war service, he came to believe that women doctors were at least as competent as men; he vigorously supported women doctors' attempts to break into specialisms other than paediatrics and obstetrics.

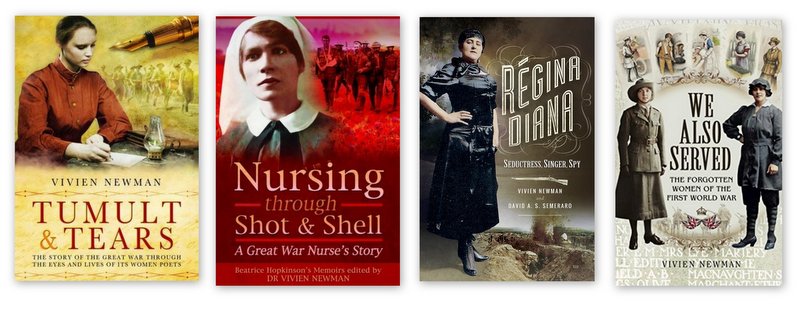

Viv Newman is the author of several books on the roles women played during the First World War. She is a regular speaker at Western Front Branch Events. In March 2018 she will be speaking at Essex Branch. She can also be heard in interview with Dr Tom Thorpe in 'Mentioned in Dispatches'

Viv Newman is the author of several books on the roles women played during the First World War. She is a regular speaker at Western Front Branch Events. In March 2018 she will be speaking at Essex Branch. She can also be heard in interview with Dr Tom Thorpe in 'Mentioned in Dispatches'

LINK TO > Mentioned in Dispatches

Introduction

For many people, the Great War is defined by its poetry; the names Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen, Edward Thomas trip off the tongue as easily as Ypres, Loos, the Somme. Despite familiarity with 'war poetry', it nevertheless comes as a revelation to many people to learn that during the war and in its immediate aftermath, hundreds of women also wrote thousands of poems. These poems appeared in newspapers, magazines, association newsletters and private correspondence, as well as being published in single volumes and anthologies. That such a corpus exists is in fact unsurprising, because women were far from bystanders in this 'total' war, and both civilian and uniformed women poeticised the range of their experiences.

Unsurprisingly, much uniformed women's service was quintessentially 'feminine': although 'some of us are nurses', many 'are merely cooks', while others 'sit in the sewing-room and sew on eyes and hooks'.2 But thousands of women spent months and years in uniform, close to the guns; like their uniformed male counterparts, they too found language to convey the horrors they were witnessing:

Hills on fire and the valleys smoking, and

the few bare trees spitting bullets ...

Always guns and more guns ...

and no ways of escape.3

Women's poetry offers Great War historians and interested amateurs a valuable, informative, sometimes amusing, other times harrowing view of the frequently overlooked contribution uniformed women made to Victory during the time when they too were 'soldiers'.

Women's war service

During the war, more than 100,000 British women joined the countless official and semi-official women's organizations established, like the Women's Auxiliary Army Corps (WAAC, January 1917), or extended, to assist the war effort, many formed by women themselves. Some women volunteered for a few hours weekly, others spent years overseas, not infrequently within earshot of the guns. Women's reasons for enlistment were varied, ranging from the desire to escape humdrum jobs or the boredom of their parents' drawing rooms, to patriotism and the conviction that they should assist Britain in her hour of need. Some women enlisted to avenge a man's death; some were pressurised by families keen to have a daughter in uniform; others defied their families when they enlisted in the embryonic women's auxiliary services. A few women found themselves inadequate to war's demands, but many discovered undreamed of reserves of character, courage, determination - and an ability to capture their experiences in poetry. Although the poetry written by these women has aroused little scholarly interest it repays examination both for the tale it tells of service life and death, and for its grassroots insights into women's uniformed service.

'I've worn a khaki uniform ... Significant indeed' 4

Pre-war, many women's lives were severely restricted: the mere accident of birth rigidly controlled their activities, employment, social groupings, even dress. When war was declared, many women, were as desperate as 'the boys' to acquire a uniform, the 'outward and visible sign ... of forming part of a great community, banded together in a common cause'.5 Additionally, having laid aside civilian clothes (often symbolic of female frivolity), uniformed women's involvement in and contribution to the 'cause' would be 'visible', what they were doing 'all could see'.6 From the beginning, the women's Commandants sought what they considered suitable uniforms: although femininity seemed desirable, sexuality needed to be contained. The 'khaki jacket chosen [for other Ranks] had side pockets ... but no breast pockets. ... These would emphasise the bustline'.7 Almost inevitably, once it was acquired, many women found neither the uniform nor its colour flattering: 'Gladys fell down last night, no men were on the scene/For if they had been they'd have seen her stockings coloured green'.8 Nevertheless, the uniform's symbolism was valued; like her colleagues WAAC Isabella Grindlay:

Would not change it now,

Not even for a model from Paree ...

'Tis old and scarred but what care For that?

I'm very proud to wear an army hat.9

Whatever the women felt, men were not universally enthusiastic about these khaki-clad militarised women, perhaps because, almost irrespective of age, women could choose to don uniform whilst a man's civilian clothes were a visible, outward sign of either his years or his unwillingness/inability to enlist.10 Poet Jessie Pope, aware of the mixed feelings uniformed women aroused, seeks to reassure her many readers that uniformed women have not abandoned femininity:

"... though the tasks they tackle

Make them mettlesome and rough

There's a woman's heart beneath each

khaki kit."

For Pope, these tasks (frequently identical to those performed by working-class women in civilian life) are glamorised by the uniform, which appealed to those who anticipated wearing it. The reality was less attractive:

Old Range ...

Your soot has often made me sneeze,

Your steel I've polished on my knees,

I've scraped some scores of spots of grease

From off your top.'2

Although the cleaner/poet shows that this 'range' being situated in a 'Home of our wounded Tommies' makes the unpleasant job more bearable, she nevertheless expresses her delight at handing over this chore to 'Jean', a luckless co-worker.

Turning 'their backs upon Blighty'

WAAC workers and Chief Ordnance Office Staff, Rouen 1917

Between 1917 and 1919, around '100,000 women passed through the various [women's] auxiliary services', some 9,625 WAACs serving in France.13 By undertaking the multiple non-combat tasks soldiers had hitherto performed, WAACs freed a man for the firing line.

Unsurprisingly, those (or those whose loved ones) were 'released' for the Front were not always grateful. These sentiments lurk beneath this sarcastic poem:

Have you heard of the latest advance?

I don't mean of Tommies or Jacks,

But this awful invasion of France

By these wonderful women, the WAACs.

For good measure,

Having filled all our places at home,

They speedily turned their backs

Upon Blighty and set out to roam,

Over France, did these wonderful women,

the WAACs.

According to this poet, these women 'soldiers' invaded France, Tike locusts they spread', ready to wreak havoc on the smoothly-running Lines of Communication. Fortunately, WAACs had their defender: one Sergeant Sumner chides those

who despise them though female they be ...

Doing a duty, a most noble breed,

Supporting our country in its hour of need

Laughed at by many, painted jet black ...15

So much for the male view, but how did serving women see themselves? Poetry by and about WAACs, in private papers, letters, diaries and Ripples from the Ranks, gives a 'fascinating insight into WAAC life and daily incidents'.16 Pausing briefly over Ripples, the title page is productive, the poet specifying that she is '3617 Grindlay'. By including her service number and omitting her Christian name, Grindlay de-personalises herself and stresses commonality rather than unique experiences. The opening poem shows how every recruit must divest herself of her identity, or at least try to. She is a cog in the machine; failure in her tasks lets down both 'Country' and 'Corps':

And some of us are old and staid,

And some of us are young and good,

And some of us are sad of heart

And some of us are light and gay.

We are soldiers one and all

And all must march the selfsame way.18

Grindlay's superficially light-hearted poems introduce us to service-life, the seeming purposelessness of some activities - 'Red tape is horrid stuff!'18- the witty misery of others when army boots can dampen even an ardent recruit's patriotism:

I'm happy from the ankles up,

How happy I can't tell,

But, from the ankles down, alas!

I do not feel so well.'19

If we listen carefully, we find that many servicewomen's writings are multi layered: the woman feeling herself to be part of the organisation and, in a wider sense, of the nation's war effort, yet there is also an individual with her own identity:

Just now and then I feel a little downed

My patriotic fervour seems to fade;

I grow impatient of the daily round

My temper gets a little worn and frayed.20

Even the most enthusiastic member can weary of the communal life with its restrictions and lack of privacy; frictions surface. Sometimes another WAAC's foibles irritate almost beyond endurance:

Now Peggy babbles all the time of Edward.

Her chatter is an endless rhyme of Edward.21

If something happened to 'Edward' all would surely rally round; currently, 'Peggy' is a bore. One woman's gnawing anxiety does not instantly evoke compassion amongst colleagues. There are transient relationships, 'friendship's ties are scarcely knit/Until they must be broken', envy of colleagues who have achieved the coveted overseas posting, 'Abroad she now must roam,' and barbs aimed at those joining a rival service: 'Go, dainty maid, your needle ply/Among those daring men who fly'.22 There is also a hint of guilt: 'In our conversation here,/We may have been a bit severe'.23 Rules appear endless, women are warned that 'There's no nonsense in the army',24 and the hierarchy between women must be respected: 'You can't be seen with me -/I'm just a private, as you see'.25 Whatever the photographed rows of smiling faces suggest, these women did not shed their personalities at the entrance to the Camp, and long hours spent in each other's company and seemingly petty restrictions could cause minor irritations to spiral. Although many women yearned for an overseas posting, once this materialized, life spent almost totally in female company could be irksome. The arrival of male soldiers was a welcome event:

If you're walking, call me early, call me early Rosie dear

Tomorrow may be the happiest day of all the year

For the Sergeants of the Ordnance are coming here today

And perchance their funny faces will drive dull care away.25

From its foundation, potential fraternisation between WAACs and service men and the possibility of scandal preoccupied WAAC officials. In 1917, unfounded salacious rumours suggested that WAACs were being sent to France to service army brothels, pursuing 'trades that you can't find in books'; WAAC Commandant Gwynne-Vaughan confronted and refuted these allegations, commenting: 'immorality is an excellent stick with which to beat a Corps of women'.27 When drawing up rules, Gwynne-Vaughan believed her approach to relationships between male and female personnel was pragmatic and open- minded - 'walking out' would be tolerated, within strict limits. Not all WAACs were impressed to find they were only allowed to walk with their Best Boy in designated areas:

There are some rules made for Abbeville

And the founder you feel you could choke

You walk fifty yards with your best boy...

You mustn't walk half an inch more.25

To make matters worse, if WAACs disobey, 'P is for Patrols, those limbs of the law/Alert and suspicious, WAACs tremble before.'29 Again, we are given hints of tensions, this time between a 'worker' and her 'superiors' who are intent on policing her and her behaviour. Interestingly, despite' a number of peticised complaints, this WAAC finally acknowledges, 'It's a swanky camp this in Abbeville.'30 There is a hint in the stressed this that the Abbeville women considered themselves superior to those in the much smaller camp in nearby Wimereux, 'seldom without its problems.'31 Whilst the Corps' official historians were predominantly educated, privileged women who had a particular and understandable need to emphasise the experiment's success both in terms of inter-female relationships and relationships with the Army, ordinary WAAC poets provide a more down to earth account of the lives of women who were taking their first steps into the masculine world of the armed services.

'I wish my mother could see me now'

WAACs were not the only uniformed women to poke irreverent, poetic fun at themselves, their illusions, their comrades and their service. Most issues of women's newsletters and gazettes (serving similar purposes to men's trench newspapers) contained a mixture of gossip, photographs, drawings and poems ranging from simple ditties to verses providing insights into the writer’s everyday service life, and, by extension the life of those performing similar tasks. 32 The prevailing poetic sentiment was a mixture of pride at what the write and her Corps were collectively achieving, and bemusement at the transformation wrought in women’s lives:

I wish my mother could see me now,

With a grease-gun under my car I used to be in Society once,

Danced, hunted and flirted, once!

Had white hands and complexion once!3

This veteran now casts a wry backward glance at early illusions; she once imagined war was a glorious game:

We used to fancy an air-raid once,

Called it a bit o f excitement once,

Prided ourselves on our tin hats once!

Now I am F.A.N.Y.34

Such naivete is long gone, war is one monotonous round of grinding work and heartache, warmed by knowledge of the FANY's indispensable war service. Like WAAC poems, some FANY verses are satirical and hint at ill-concealed tensions: '10 Little Fanny volunteers in France/ One didn't like to work, wished to go and dance.'35 So, according to one FANY 'Corporal and Head Cook', the young drivers availed themselves of opportunities to 'dance', have 'lunch [...] with the 'Medecin-Chef' and, when returning 'to Blighty/Stop [...] in Paris on the way to buy a naughty nightie!'36 Whether factual or not, the verses hint at how this poet, perhaps jealous of the drivers' relative freedoms, imagines they behave when out of camp.

Like all uniformed women, the members of the Scottish Women's Hospital Units [SWH] had marched to war full of naive enthusiasm; they served on the Western and Eastern Fronts - where they were dubbed 'Little Grey Partridges'. Nursing French troops in the Abbaye de Royaumont on the River Oise, SWH women discovered that life as a 'soldier' was full of minor irritations as well as heart-ache and trauma:

If you can rise though no-one comes to call you

And share one candle with five gloomy friends,

If you can eat cold porridge in the cloisters,

When in the darkness salt with sugar blends ,..37

Undeniably, verses about 'cold porridge', ‘beastly drill’ and resentment that when ‘you meet one of the officers/You’ve bally well GOT TO SALUTE’ [sic] Are the stuff neither of great poetry, nor of ‘official’ history, but they provide tantalising insights into women’s everyday service life by those who experienced it 90 years ago.

Casualties amongst uniformed women

Grave of Sister Mary Gray at Asniere-sur-Oise

‘We troop in silence o’re the crest/Of the hill to take her away to rest.’ 39

When the women's corps were formed, women were recruited to 'Come and Help';10 it was not assumed that they would come into direct contact with the enemy or die as a result of their service. Nevertheless, all women were prepared to lay their lives down if so required and the first female death overseas occurred on 23 November 1914.11 Accounts, photographs, and the occasional poem survive about women's funerals at the Front. SWH Nurse Mabel Jeffrey writes poignantly about the funeral of Sister Mary Gray on 23 January 1916. Uniformed comrades in 'workaday garb of blue and grey' followed Gray's coffin which was draped with, 'her country's flag, white flowers and green,/Tokens of thanks for the life that has been.'42

On 30 May 1918, the WAAC suffered its first casualties through enemy action: nine women were killed in Abbeville, They were buried with 'full military honours', the 'RAF... circling round the cemetery during the ceremony.'43 Although there was considerable media hysteria, no poetry seems to have been written (or preserved) relating to this event, when for the first time, servicewomen became and were accepted by women (less by men) as legitimate targets. The Abbeville casualties were newcomers to France; ironically, the established women 'felt it somehow inappropriate that this honour [of being killed] had fallen to new arrivals'.11 Further raids remained a potential hazard, one imaginative Wimereux WAAC circumventing the problem: 'my head felt rather unprotected so I wore a small tin basin with a cushion inside and felt much happier.'15 Being unglamorous domestic personnel, having pudding basins available had some advantages! Parenthetically, WAAC tin hats arrived 'about a month after the Armistice.'46

If many uniformed women's funerals were attended only by serving comrades and officiated at by Army padres, the (unique amongst women) wartime state funeral of SWH founder Dr Elsie Inglis was an event of major importance in her native Edinburgh. Inglis, who served on both the Western and Eastern Fronts, died in November 1917. Her actions, her total commitment to the wounded in her care, to the Hospital Units she founded and finally her self-sacrifice came to epitomise for many the nobility of women's wartime service, 'A loving, kindly woman's heart you brought/.../out poured it all/In perils of the road the field the mountain'.17 Although Inglis achieved temporary posthumous fame most women’s lives and deaths went un-noted. In the words of the Dead Woman's Penny, they too 'passed out of the sight of men by the path of duty and self- sacrifice'.

'Things which will abide': Fannies',

WAACs' and Little Grey Partridges'

post-war 'Precious Memories' 48

Although historians comment upon Old Soldiers' Associations, they frequently overlook those of serving women who were equally eager to preserve the memories of their war service, to recall the good and the bad times. Associations' immediate post-war newsletters are marked by a sense of anxiety: by late 1918, 'Q is the Question as to where we shall go' appears in acrostic poems, the answer is grim, 'W is the Workhouse'.19 Of course, few women had a guarantee that their job would be available at the end of the war; they had resigned their civilian jobs, not for 'the Duration' but forever.

As time passed and women struggled to reintegrate themselves into civilian life, they sought to retain their links: newsletters helped maintain contacts and preserve memories. Officially constituted in December 1919, the WAAC Old Comrades' Association newsletter kept ex servicewomen in touch.50The poems and jottings are generally nostalgic, looking back to good times and camaraderie, and laughing about former irritations. The newsletter affirms women's pride in having belonged to the Corps and sorrow that it, if not its raison d'etre, has ended. Several poems remember

dear dead days that never come again …

when sorrow and when joy, they both were ours

And the war was not all sorrow and all pain.51

After the Armistice, although most uniformed women reverted to the 'private' sphere, their thoughts roamed back to days of being 'care-free WAACs who'd done their little share/To win the war'; such sentiments dominate newsletters.52 Differences and tensions dissolved now; ties forged between women who shared a uniform proved binding, being reaffirmed when reunions took place:

hearts forget in peaceful joys,

Their troubles and their pain,

And weave for many an absent hour

Sweet memories that remain.53

For the Little Grey Partridges, their (post war) 'Royaumont Song', to the tune of 'John Peel' encapsulates nostalgia for their beloved Abbaye:

For the sound of the name to the heart brings a thrill

And the spell that it cast, it is over us still,

Could we forget, even had we the will

Royaumont, Royaumont in the morning 54

Some Associations survived another war, folding only when most members had themselves died, the Royaumont women keeping theirs alive until 1973; its winding-up was mourned by the frail survivors: 'It's just that I have outlived everyone I ever worked with ... I among others miss the newsletter, it is a tender link and keeps us informed'.5The flimsy letters, (which a few women donated to archives sensing an historical importance reaching beyond the sad catalogue of rheumatism and influenza), their cherished Gazettes and the poems they wrote, provide powerful evidence of the strength of servicewomen's bonds. Reading this preserved correspondence sent from genteel nursing-homes, it is hard not to be moved to tears by the strength of feeling and sorority between these now elderly women who, like old soldiers, jealously guarded memories of those indescribable, distant days:

Things which will abide,

The Friendships made, the fellowship of our band,

The memories for us all of work and play.

The spirit which carries on whate’er betide.56

Conclusion: 'We helped to beat the Boche 57

QAIMNS nurses and VADs going on duty via charabanc

During the Great War, uniformed women undoubtedly occupied an ambiguous position. They were sometimes accused of 'aping men in a tasteless parody of the real army'.58 With so much photographic and textual copy presenting smiling faces and capable girls, fears spread that our 'superb' women were relishing the War.59 In their writings, women undeniably hint at their excitement at the sudden unexpected opportunities the conflict provided. As with men's verses, there is a sense of living life to the full: even the most prosaic tasks became glamorous 'war work' if performed for Tommy. Women's writings also give a glimpse of the disruptions and tensions this new life was creating; poems provide an alternative, sometimes entertaining view to the one contained in Corps' official histories. Poems show women striving to find ways of serving their nation and demonstrate poets' awareness that by wearing uniform women have stepped outside their gendered roles and are inexorably altering women's relationship with the Armed Services.

Uniformed women's writings remind us that despite the various ways they were constructed by the media or by recruiting sergeants, women in uniform could bond with or despise each other; some women worked tirelessly in the background, others ostentatiously sought the limelight. Significant numbers of women reached the war zone that supposedly 'Forbidden Zone' to women; here they tended the wounded, comforted the dying, were the targets of enemy fire, worked on the Lines of Communication, and did what male soldiers have done through the ages - peeled potatoes, washed socks, filled in forms ... and wrote poetry. Sometimes this poetry is mere doggerel penned in an idle moment to vent frustration, entertain colleagues and capture a memory. At other times, it is a powerful reminder that women not only went to war, they found new ways of describing it, new ways of reminding us that they were forging a path for future generations of women. These women became an integral part of the 'monstrous landscape of the superb exulting war', and they too are war poets.60Their poems offer us a wealth of alternative source material for exploring how uniformed women behaved, interacted and saw themselves during those four long years when they 'helped to beat the Boche'.

References

1. Pope, Georgina Fane: 'Nursing in South Africa During the Boer War', British journal of Nursing, 20 September 1902, p. 232.

2. Stephenson, Gwendoline: Idle Thoughts of a VAD (Stockwell nd).

3. Borden-Turner, Mary: 'Where is Jehovah?' 'The English Review Volume 25 July-December 1917, p. 97.

4. 3617 Grindlay, I.: 'The Parcel', Ripples From the Ranks of the Q.M.A.A.C. Erskine Macdonald, 1918, p. 17.

5. George, Gertrude: Eight Months with the Women's Royal Air Force (Heath Cranton, 1921) np.

6. Hamilton, Helen: 'The Writer of Patriotic ad.' Napoo A Book of War Betes-Noires, (Oxford, 1918), p. 56.

7. Terry, Roy: Women in Khaki (Columbus 1988), p. 44.

8. 'The Wail of a Waac' in Old Comrades Association Vol. XIII 6 1933 (hereafter OCA).

9. Grindlay, 'My Army Hat' op. cit.: p. 15.

10. For example on 6 January 1917 Graphic informed readers about Miss Gardiner

Duncan a 'Scots nurse of 70 who has been 18 months nursing in the Vosges', p. 26.

11. Pope, Jessie: 'The WAACs' from the papers in IWM DD MISC 124 item 1917.

12. No 20 Renfrew VAD Gallowhill Auxiliary Hospital.

13. Gwynne-Vaughan, Dame Helen: Service with the Army (Hutchinson [1941]), p. 71.

14. Bestin, Jan: 'The WAACs' in Birmingham Collection, vol. 34, p. 7.

15. Sgt. Sumner: 'Only a WAAC' in The CRO 15/3/19 np.

16. Times Literary Supplement, October 31 1918, p. 537.

17. Grindlay, 'The QMAAC', op. cit.: p. 7.

18. Grindlay, 'The Hanky-Box Lid' op. cit.: p. 40-1.

19. Grindlay, 'Route March Sentiments', op. cit.: p. 10.

20. Grindlay, 'The Parcel', op. cit.: p. 17; 'Leave' p. 11.

21. Grindlay, 'Edward', op. cit.: p. 13-14.

22. Grindlay, 'Departing Comrades', op. Cit.: p. 61 ff.

23. Grindlay, 'Departing Comrades', op. Cit.: p. 61 ff.

24. Grindlay, 'Carry-On', op. cit.: p. 57.

25. Grindlay, 'Potter', op. cit.: p. 36.

26. 'The Wail of a Waac', Old Comrades, volumes XIII, no.11. 15 May 1918

27. Terry, op. Cit. p. 70; Gwynne-Vaughan, op. cit. : p. 50.

28. A. Gebbert, WAAC A Comer in Abbeville', Papers of Maude Emsley National Army Museum APFS 1994-01- 248.

29. 'The Cadets' Alphabet', OCA Vol. XVIII, 7 November 1938.

30. Gebbert, loc. Cit.

31. Gwynne-Vaughan, op. cit.: p. 33. Between the two camps there were over 7000 women in early summer 1918, with the majority of workers in Abbeville. Precise numbers have not been preserved. Figures from Dorothee Platz PhD thesis (2004) 'We had been the Women's Army' Das Women's Army Auxiliary Corps. Kriegserfahrungen von Frauen im Hilfsdienst der britischen Armee des Ersten Weltkrieges. Appendix 'QMAAC Mannschaften in 083. Frankreich' University of Tuebingen.

32. The largest preserved collection appears to be Women's Volunteer Reserve Magazine held by the British Library. This has articles and poems about the various tasks volunteers performed.

33. 'One of the Saints', 'F.A.N.Y.' F.A.N.Y. Gazette, March 1918 np.

34. ibid.

35. McLure, N.: 'The Adventure of FANY 12', in F.A.N.Y. Gazette, November/December 1918.

36. Ibid.

37. Mackenzie, Geraldine: 'If' - Dedicated to the Night Orderlies of Royaumont, Newsletter of the Royaumont and Villers-Cotteret Association 1923-1973.

38. 'The Wail of a WAAC' loc. cit. 'Some Waac' Old Comrades Association 3 September 1937; A Gebbert, loc. cit.

39. Jeffery, Mabel: 'In Memoriam' in Cornish, John and Wenzel, Marian: Auntie Mabel's War Her Part in the Hostilities 1914-1918, (Allen Lane, 1980), p. 53.

40. WRAF recruiting poster.

41. Staff Nurse, Ethel Fearnley, Queen Alexandra's Imperial Military Nursing Service 23 November 1914, buried in Boulogne.

42. Cowper, J. M.: A Short History of Queen Mary's Army Auxiliary Corps (pamphlet), p. 54-5.

43. Gwynne-Vaughan, op. cit.: p. 57.

44. Turner, Isobel Agnes: 'Joining the WAACs, 1917' (recollections), NAM (National Army Museum), APFS (Archive, Photographs, Film, Sound) 1998-01-107:3, p. 3.

45. Turner, loc. cit.

46. J.M.D. 'Elsie Inglis', The Scotsman, November 1917.

47. Women's Volunteer Reserve Magazine, March 1919, p. 57.

48. FANY Gazette, 20 December 1918.

49. Gwynne-Vaughan, op. cit.: p. 72.

50. 'Bristles', OCA October 1921, p. 7.

51. 'Bristles', loc. cit.

52. K. K.: 'Shanghai in June', OCA June 1923, p. 5. '(Shanghai' was the Rest/holiday Home acquired for former WAACs; many seemed to have relished their time spent there.)

53. 'Royaumont Song: D'ye ken Royaumont' held in the papers of SWH Nurse Miller, Peter Liddle Collection, Brotherton Library, University of Leeds, WO 083.

54. 'Large' Wilson to Miss Miller Liddle WO

55 .Women's Volunteer Reserve Magazine, March 1919, p. 57.

56. Anon. 'The 'WAACS', in WAAC Magazine, January 1919 no. 3, np.

57. Thebaud, Francoise: 'The Great War and the Triumph of Sexual Division', in ed. Francoise Thebaud, A History of Women in the West: Toward a Cultural Identity in the Twentieth Century. (Belknap Press 1944), pp. 21-75, p. 34.

58. Alec-Tweedie, Mrs, Women and Soldiers, John Lane, London, 1918, p. 92.

59. Borden-Tumer, 'The Hill', The Forbidden Zone (Heinemann, 1929), p. 175.

60. Anon. 'The "WAACS'", in WAAC Magazine, January 1919, no 3, np.