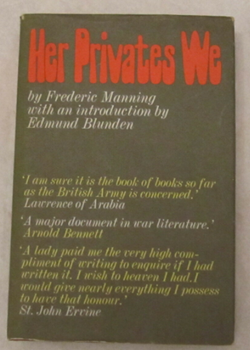

Her Privates We by Frederick Manning

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- Her Privates We by Frederick Manning

There is an introduction from the author and poet Edmund Blunden; he describes ‘Her Privates We’ as a ‘new kind of candid, reflexive writing’. Ernest Hemingway loved the book. It had me thinking of Norman Mailer or Henry Miller. It is certainly from the same Pantheon as Erich Maria Remarque (All Quiet on the Western Front), Robert Graves (Goodbye to All that) Blaise Cendrars (The Bloody Hand) and Ernst Junger (Storm of Steel).

When first published the author gave his Regimental number not his name. Frederic Manning, already a successful writer, had wanted to remain anonymous and for the story to speak for itself. He states that what he wrote was fictional, but you sense this was said to protect men who he would not want to think he had characterised them unfairly because he also says that he felt he had made ‘a record of their words’ and had heard the ‘voices of ghosts’ when writing. The dialogue is engaging - you hear it rising from the pages like voices from a top-notch BBC 4 radio drama.

The fact that Manning died in 1935 (he smoked and drank heavily) might explain why his work is so unknown: not for him the decades of success that established the lasting reputation of the likes of Robert Graves or Ernest Hemingway.

I found myself immediately drawn into the narrative which follows a few months in the life of Private Bourne. The first paragraph alone is as evocative and engaging as the first minutes of the Sam Mendes film ‘1917’ as Bourne comes in from an attack and looks for respite in the first ‘ole in the ground’ he stumbles across. For a moment you wonder if he is in the German line in error.

‘Her Privates We’ is a record of the experience on the Somme and Ancre fronts during the latter half of 1916. The story is character driven and the style more literary than will suit some people’s tastes. Though clearly written from experience it is not an account of a specific event or people.

We see, hear, feel and smell the place.

Dialogue with an accent is written out phonetically like Irvine Welsh’s ‘Trainspotting’. You know that Bourne, as he is referred to throughout, is a misfit. He’s from another ‘station’, a different walk of life entirely than that of the men whose company he prefers to keep. We get philosophy and reflection from his perspective on the lot of the ‘ordinary working man’. Bourne wants the experience with the ‘lads’ not as an officer or NCO. The day to day workings of a company between junior officers, NCOs, the cook, quartermaster and men is revealed.

We experience how the average Tommy lived a lot and loved a little behind the lines, between billets, while on a quest for treats and then during preparations before going over the top. We feel how men behaved, died or survived.

‘Averages are too colourless, indeed too abstract in every way, to represent concrete experience …’ he muses.

We get to know Bourne (aka Manning) very well.

A misfit known by what he did in civilian life but his reluctance to take a commission. His generosity to others. A gent with his gifts. Someone who craved action to replace the boredom, who enjoyed periods of isolation. For most ‘company guard’ was a chore, not for Bourne who ‘liked the solitude and the empty night … with its enchantments changing even this flat and unlovely land into a place haunted by fantastic imaginings’, where he experienced on a frosty night ‘a silence so intense that he almost expected it to crack the ice’.

Though when it came to being too keen he took the advice of one of his mates not to go ‘lookin for no Victoria Cross. You want to be bloody careful you don’t get a wooden cross instead’.

We see and hear how men were killed, not with the apocryphal shot through the head as put in letters home, but ‘blown into fragments by a high explosive shell’. We see the ‘gray face’ that is senseless and empty of a dead soldier propped up in a trench, an image that haunts us from the photographic library of the Imperial War Museum and haunts us in the final pages of the book. The scenes of death are vividly portrayed with lines such as ‘The look of puzzlement on a man as he died after having had both his legs blown off’ or the shock of seeing a man with most of his guts blown out’. This is a sight and experience my late grandfather recounted in mounting detail to me as a boy growing up of a man in his company who took a couple of days to die having been hit in the stomach by shrapnel. He waited a few hours for his friend to ‘stiffen up’ before burying as best he could. Such was the reality of war.

There is humour throughout. The constant mangling of the French language is a delight to read, itis ‘Franglais’ at its funniest with the with unexpected drama for a man who thinks he is being polite to say to a woman how lovely it is to get ‘cushy avec mademoiselle’. And there are the songs too, with ribald renditions of ‘parley-voo’, ‘auprès de ma blonde’ and ‘mademoiselle from Armentieres’.

There are so many moments such as these that provide insights to the human condition which are as meaningful today as when the lines were written; he describes, for example, ‘men concealing their emotions, but not that they were concealing their emotions’.

There are moments of genius too with the English language, such as the simple act of a man folding a blanket neatly described as ‘though he were folding up something he had finished with and would never use again’.

We get Bourne’s perspective on desertion and execution, in this case deferred and the man escapes custody never to be seen again. And we are reminded of the true nature of trench warfare - the boredom that had to be endured, ‘I would rather be dog-tired than bored’, he reflects.

Stoical and indifferent, Bourne is surprised when he develops a crush on a girl. He may even be feeling he pangs of love. ‘It was something about her neck’, he muses ‘the back of her small head, and the way her little ears were set, flat against the bright hair …’.

Finally, though we arrive there gradually, the four muckers, Bourne, Ben, Shem and Martlowe go over the top. We have their thoughts on the planning for this, and listen in on the perennial discussion on whether it is best to go over in the first or second wave. The only thing that they can agree on is the importance of going over the top with a full stomach.

My quest, thirty years now after my grandfather’s death - he served as a Machine Gunner (Corporal) during Third Ypres, is forever to get as close to an understanding and experience of the reality of life and death on the Western Front for the British soldier. Even hours of interviews with my grandfather (he died in 1992) lack the insight that Manning provides.

I’m now reading ‘Her Privates We’ for a second time and recommend it highly to others. There's a film to be made ...

Review by Jonathan Vernon. Digital Editor