Two Colored Women with the American Expeditionary Forces by Addie W Hunton and Kathryn M Johnson (1997) Introduction by Adele Logan Alexander

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- Two Colored Women with the American Expeditionary Forces by Addie W Hunton and Kathryn M Johnson (1997) Introduction by Adele Logan Alexander

325 pages, 520 including a biography of Adolpheaus Hunton.

(1997) Introduction by Adele Logan Alexander

GKHall & Co

Illustrated throughout with ornate collages and collections.

Hardcover first edition as part of the the African-American Women Writers 1910-1940 series, under the general editorship of Henry Louis Gates, Jr. and Jennifer Burton

Addie Hunton and Kathryn Johnson served as ‘secretaries’ in YMCAs in France during the First World War. A black suffragette, Addie Hunton had already spent time in France with her family studying in France and Germany before the war. She wasn’t the first black woman to make it to france, previous African American women hoping to serve behind the lines had been returned home as ‘persona non grata. This initial resistance to accept African Americans in any role, was eventually overcome.

Musee de la carte postale. https://artsandculture.google.com/asset/brest-road-at-camp-hdqtrs-pontanezen/_gHPH7sBNy5cjA

The experience documented in ‘Two Colored Women’ is of time spent with some of the 25,000 African American soldiers on the West Coast of France who served as stevedores, labourers and engineers connecting American to Chateau Thierry, Verdun, Sedan and St.Mihiel.

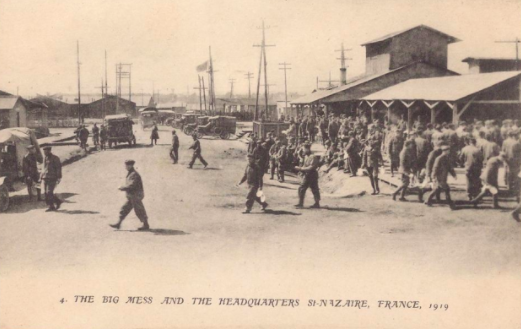

The women had direct personal experience of the camps at St.Nazaire and Brest, and when on rest leave with the men at camps near Chambery on Lake Bourget at and Challes-les-Eaux, as well as on their travels to the YMCA HQ in Paris, and trips south to Bordeaux and Marseilles. Like many of their brethren, their many efforts to be sent to the Front Line fell on deaf ears. Their experience of staying with French families was entirely positive, feeling they were treated as family members.

Mischievous attempts to tar the reputation of black men was prevented by the French.

Their accounts are bittersweet and observational. The hurt and sometimes horror of discrimination meted out on African American servicemen is ever present with a list of racial slurs, the “mean prejudice and subtle propaganda” (p. 325) and men being “goaded by prejudice beyond reason’ (p. 302).

As well as the usual privations of war; the hunger and thirst, fatigue, smoke and noise, and the danger of combat for those who made it to the front line, there were “days when terrible discriminations and prejudices ate into the soul deeper that the oppressors knew” (p.275 “Army restrictions were as numerous and as intricate as the barbed wire entanglements of the front”. (p. 308)

Despite being the very thing many African Americans had hoped to escape by enlisting, during training in American and once in France, they found that the white command, officers and soldiers governed by Jim Crow laws, written and assumed, whereby racial discrimination and segregation was enforced, despite being sent to fight to ‘defend democracy’.

African American soldiers had inferior quarters, deficient jobs, and suffered harsh rebukes compared to the white American soldier. No coloured Americans were permitted in the Victory Parade through Paris in 1919. Just two examples, on 21 January 1919 General Pershing made a trip to review the troops of the 92nd Division. On arrival he found all the coloured troops had been deliberately put to work to have them out of sight and on 1 April 1919 there were race riots in St.Nazaire after a white French Women entered a restaurant frequented by white American soldiers with a Black French Soldiers. Insults flew and a riot broke out.

African Americans were expected to police themselves against ‘race animosity’. When their own commander issued the request ‘Don’t go where your presence is not desired’ it was greatly resented.

The writing style often is somewhat grandiloquent, even ornate, with distinct religious overtones, such as this description of African American labourers who were put to burying the dead: “Whose would be the hands to gather as best they could and place beneath the white crosses of honor the remains of those who had sanctified their spirits through the gift of their lifeblood.” (p.298)

As a result of the YMCA’s army schools it was felt that African Americans who had been illiterate and unschooled returned across the Atlantic with a new impetus and vision based on their travels, and contact with the French people and so would be better equipped for ‘citizenship and future service’.

On a positive note, schools were established to teach the illiterate to read and write and provide a limited education to the others. Albeit, amongst their number there were both college graduates and undergraduates. The Mayor of Chambery invited African Americans staying at the YMCA at Challes-les-eaux to come and live in France.

YMCA Building, huts and tents for colored (sic) soldiers.

- Bordeaux

- Brest

- Le Mans

- Challes-les-Eaux

- Chambery

- Marseilles

- Joinville

- Belleau Wood

- Fere-en-Tardenois

- Orly

- Is-sur-Tulle

- Remacourt

- Chaumont

- Camp Romagne

Reviewed by Jonathan Vernon, Digital Editor, The Western Front Association

Additional Reading (reviewed on our website) :

Ely Green ‘Too Black, Too White’ : an autobiography of growing up Black in America in the 20th century

The Unknown Soldiers : Black American Troops in World War One

Rayford W. Logan : The Dilemma of the African American Intellectual

Paris Noir : African Americans in the City of Light by Tyler Stovall

Scott's Official History of the American Negro in World War 1

Freedom Struggles : African Americans and World War One by Adriane Lentz-Smith

Mentioned in Dispatches Podcast:

African American Serviceman during World War One