A soldier of the Cheshire Regiment - thrice missing: Private Peter Mahon

- Home

- World War I Articles

- A soldier of the Cheshire Regiment - thrice missing: Private Peter Mahon

On the day I began writing this article, 11 November 2020, I reflected, as did we all, upon the burial of the 'Unknown Soldier' on this day a century ago at Westminster Abbey. He was, of course, one of the many 'Missing – Known unto God'.

What follows is an attempt at revealing something of the story of a soldier. Again, one of the 'Missing. Killed in action', but also missing from some of the records of the soldiers who fought in the First World War.

Private Mahon’s name appears on the War Memorial in Middlewich, Cheshire, but it does not appear in the semi-official list of Soldiers Died in the Great War published in the 1920s or in the Roll of Honour in the History of the Cheshire Regiment in the Great War - A. Crookenden, Evans, Chester 1939.

This was puzzling and I resolved to find out why.

My enquiries did not start well because I was mistakenly informed that Private Mahon served with the 7th Battalion, Cheshire Regiment.

It occurred to me that there could have been a problem with Private Mahon’s name. Mahon indicates Irish ancestry and Irish surnames are often mispronounced and often misspelled. Sometimes the mis-spelling has become accepted over the years by families – 'Maher', for example, has become 'Marr'; 'Malone' has become 'Mullowney' and so on.

I decided to comb the names of soldiers of the in Soldiers Died in the Great War for names which looked something like or, when pronounced, would sound something like Private Mahon’s surname.

There were no similarities of the kind I was looking for in the list of the 7th Battalion - or more correctly the 1/7th Battalion.

Eventually I looked at the list of the 1st Battalion. And there, I thought, I found him. The entry reads:

'Mahore, Peter, b. Middlewich, Cheshire e. Middlewich,

Cheshire, 18769, Pte., k. in a., F. & F., 7.5.15'

Private 'Mahore' was born and enlisted in Middlewich and was killed in action somewhere in France or Belgian Flanders on 7th May 1915.

Since there is no Private 'Mahore' recorded on the Middlewich War Memorial I thought it was reasonable to assume that Private 'Mahore' and Private Mahon were one and the same person.

The confusion of names was not, as can be seen, quite as I had anticipated. The error quite possibly arose from the transcription of someone’s poor handwriting. Entries in soldiers’ Service Records are sometimes practically illegible. Transcription errors are not unknown. The Memorials to the Missing in France and Belgium, for example, have numerous neat inlays their stone panels indicating corrections of names.

I contacted the Commonwealth War Graves Commission to discover where Private 'Mahore' had been killed and where his grave was.

They had no record of any Private 'Mahore'. The record of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission shows his name correctly spelled. Private Mahon was killed somewhere in the Ypres salient and his final resting place is unknown. His name is carved on the Cheshire Regiment Panel (19) on the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing at Ypres (South side).

Private Mahon was therefore, in a sense, twice missing – once from some of the records of deceased soldiers and once, of course, as a soldier lost on the battlefield.

To complete Private Mahon’s story as best I could I referred once more to the History of the Cheshire Regiment in the Great War – and to the War Diary of 1st Battalion.

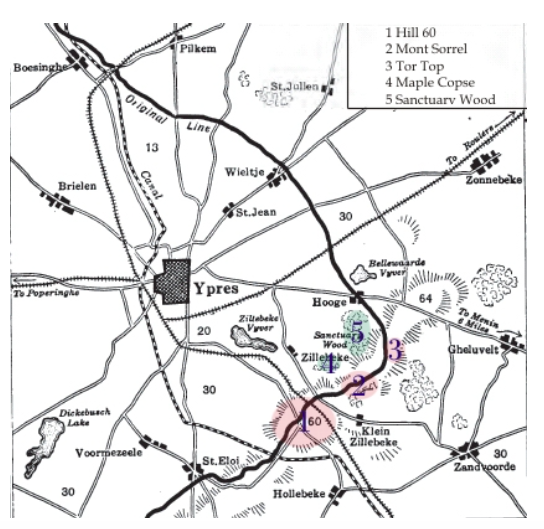

On 4 May 1915 Ist Battalion was 'in Brigade Reserve' - ie not in the front line but ready to go into action to support the other Battalions in the (15th) Brigade if necessary - and billeted in the Ypres casemates (chambers inside the thick stone walls of the city).

At 8.00 am on 5 May the Battalion was ordered to move to Hill 60 and support three trenches occupied by the Germans. (The 1st Battalion War Diary says that the Battalion was called out at 8.00 pm but 2nd Lieutenant Greg later recalled starting off from Ypres ‘… at about eight or none in the morning ….’ and this would seem correct bearing in mind the next time mentioned in the Diary which was 10.20 am.)

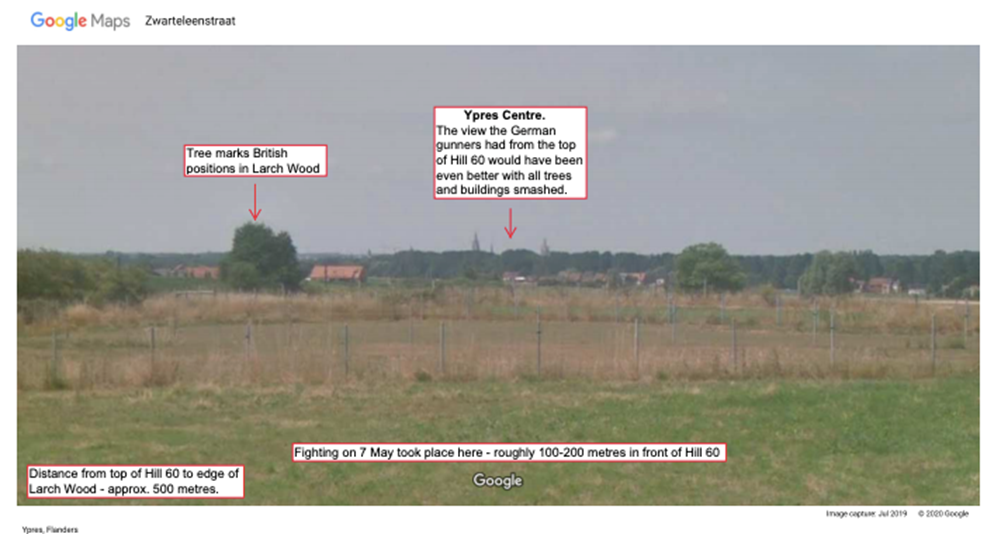

Hill 60 is not really a hill but a large somewhat elongated mound formed by the spoil taken from the adjacent cutting made for the Ypres-Comines railway. It gets its name from the fact that it is 60 metres above sea level. From the top of Hill 60 Ypres could be seen quite clearly and was an excellent site for artillery observation.

The French lost the Hill to the Germans in 1914 and when the British took over from them at the end of 1914 it was decided that the Hill should be retaken.

Because the earth of Hill 60 was soft, tunnelling was relatively easy and it was decided to blow the Germans off the Hill with mines. Probably the first British mine of the war was blown there by Lt White RE on 17 Feb 1915.

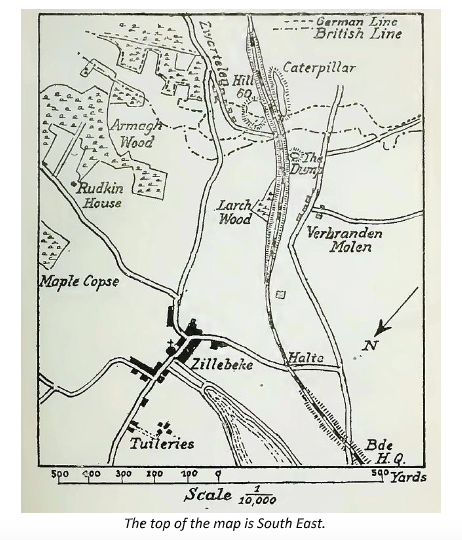

Three tunnels were begun early in March 1915 50-100 yards from the German front line. Almost immediately dead bodies were discovered and quick-lime had to be brought up to cover them. Many more bodies were uncovered in the coming months and the smell of quick lime was to hang over the Hill for several years.

The three tunnels were splayed out into six as they approached the Hill. About four tons of gunpowder in 100 pound bags were packed into the six mineheads. On 17 April the mines were fired over a ten second period. A huge quantity of earth exploded 400 feet into the air. Simultaneously, British, Belgian and French artillery laid down a barrage on the Hill which was captured by the Royal West Kent Regiment.

The Germans wanted to regain control of the Hill and launched a series of desperate counter-attacks all of which were repulsed until on 4 May they recaptured it by using poison gas.

This was why the men of 1st Battalion Cheshire Regiment found themselves facing Hill 60 on 5 May having been shelled and gassed on the way. The troops only had hastily issued mouth pads to protect themselves with. Failing that, they had been instructed to hold wetted handkerchiefs to their mouths. No proper 'respirators' were available.

At about 10.20 the Battalion got to Larch Wood - the south eastern edge of which is about 0.5 km to the north west of Hill 60 - which they had to attack and clear of Germans before they could occupy trenches in the wood and those closer to Hill 60. In the evening they had managed to get into trenches further on - about 100-200 metres north of the top of Hill 60.

Heavy shellfire continued. The Battalion’s commanding officer Colonel Scott had been killed as soon as the Battalion reached Larch Wood while three other officers were wounded. Deaths and casualties among NCO’s and the ranks were probably high but are not numbered in the War Diary or Regimental History. (Major CGE Hughes took over command of 1st Battalion. He wrote the account of the Battalion’s actions at Hill 60 in the Battalion’s War Diary.)

There was considerable confusion in the shattered trenches in front of Hill 60. A vivid account was written by 2nd Lieutenant (later Captain) Arthur Greg (see above and footnote i). The Battalion was shelled by both sides - British shells falling short of their targets on the Hill just beyond the Cheshires. The Germans occasionally managed to infiltrate the British trenches and attacked the Cheshires with rifle fire and grenades. The Battalion was almost attacked in error by men of another British regiment (the Royal West Kents who had captured the Hill the previous month).

There are apparently no entries in 1st Battalion’s original handwritten War Diary for 6 and 7 May in the National Archives (see footnote ii). Happily, the Cheshire Military Museum has a transcript of the missing entries. Evidently, on 6 May the Battalion managed to hang on in the positions it occupied the previous day and even took over three trenches from Kings Own Scottish Borderers. Mention is made of 'casualties from shrapnel' and the wounding of Second Lieutenant Greg.

On 7 May 1st Battalion 'cooperated with K.O.Y.L.I (2nd Battalion Kings Own Yorkshire Light Infantry) in an attack …. at 2,30 am.to recapture four trenches'. The result:' …. seventy yards of trench recaptured, but position untenable to lack of support from the left 'so'…. forced to withdraw ….'One officer was killed and two were wounded in addition to other casualties.

The Chester Chronicle of 5 June 1915 gives a slightly more detailed, but not totally accurate, account from an unacknowledged source.

At about 3 am on 7 May, the account states, ''A’ Company after desperate fighting, retook 70 yards of the trenches. Owing to the supports missing their way, the Cheshires were unable to hold them. ‘A’ Company in this action lost very heavily. This Company lost many officers and men.'Having been gassed, shelled, bombed and shot at continuously since 5 May the Battalion almost certainly now contained only a fraction of its full number of (1000 +) men and there had been very little chance of success. (For comparison - the Queen Victoria Rifles Battalion brought to Larch Wood to support the attack was down to 320 men.)

The attack, according to the Battalion War Diary was '…. generally unsuccessful and not renewed.' The Battalion was relieved by the South Lancashire Regiment that evening and withdrew to Ouderdom Camp 11 km to the west. British positions near Hill 60 were not to change greatly until the explosion of the mine under the Hill in June 1917.

The action on 7 May, almost certainly, was 'Journey’s End' for Private Peter Mahon. His name appeared (but not until well over a month later) as the last on a list of missing released from the Headquarters of the Cheshire Regiment at Chester Castle and published in the Chester Chronicle on 26 June 1915. His name is correctly spelled. The exact circumstances of his death are unknown and will probably remain so for ever (see footnote iii). It does not take too much of an effort to make an imaginative reconstruction of the appalling experiences of the men of 1st Battalion as they struggled in vain to win back what became known as 'the bloody pile of earth'. Peter Mahon’s remains may rest in the Larch Wood Cemetery in front of a gravestone with the inscription 'A soldier of the Great War Known unto God' carved on it; they may rest in the ruins of the Larch Wood trenches.

A local Middlewich historian, Philip Andrews, has discovered that Peter Mahon had previously served in 2nd Battalion, Cheshire Regiment, for two years and 311 days. The surviving pages of his Service Record indicate that he re-enlisted on 7 December 1914 and his age is recorded as 38 - which apparently contradicts the Census Record (see footnote iv).

Philip Andrews also discovered that the War Medal Roll indicates that his name is recorded as 'Mabon' on the Index Card rather than 'Mahon'. Perhaps Private Mahon, therefore, might be regarded as a soldier actually thrice missing – in that his name is 'missing' from another record. The Card has a note that his medals (1915 Star, British Medal and Victory Medal) were returned to the authorities.

I visited Hill 60 and Larch Wood Cemetery some years ago. I left a poppy at each place. I make a point of looking at his name on my, until recently, frequent visits to the Menin Gate. Remember the soldier 'thrice missing'. May he Rest in Peace.

Footnotes:

i) Arthur Greg was a member of the well-known cotton manufacturing family, the Gregs of Quarry Bank Mill, Styal, Cheshire. After he had recovered from the wounds he suffered at Hill 60 he joined the Royal Flying Corps. He was killed in 1917. The temporary cross which marked his place of burial is displayed at Quarry Bank Mill, as is his uniform. Some of his experiences at Hill 60 can be accessed via quarrybankmill.wordpress.com The History of the Cheshire Regiment in the Great War quotes Greg extensively. (Incidentally, this History records the arrival of 1st Battalion at Hill 60 as 4 May and the death of Lieutenant Colonel Scott as 6 May whereas the War Diary records 5 May for both events.) Nigel Cave also quotes Greg in “Hill 60” in the 'Battleground Europe' series, Pub. Pen and Sword 1998, and includes some excellent archive photographs showing the chaotic state of the ground.

ii) The absence of entries in 1st Battalion War Diary for 6 and 7 May is something of a mystery – there are none in the handwritten original Diary in the National Archives.

However, there is a transcript of the Diary in the Cheshire Military Museum in Chester and Caroline Chamberlain, the Museum Officer, kindly emailed me a PDF of the entries for 6 and 7 May 1915. So, what happened to the missing original handwritten page? My guess is that in those happy days when a War Diary could be brought to a reader on request, in what was then the PRO at Kew, and at a time when supervision was very “light touch”, somebody pinched it.

iii) Philip Andrews in ’The Fragrant Blossom of Middlewich’, Volume I, 1914 – June 1917, Pub. Synchronized Communications Ltd. 2016, mentions that the local newspaper reported that “A member (unnamed) of the same battalion home on leave sometime afterwards (no precise date) stated that Mahon was killed by accident during a bayonet charge at Hill 60.” The same newspaper mistakenly reported the date of his death as 12 May – when 1st Battalion was no longer at Hill 60.

iv) The 1901 Census for Middlewich reveals that Peter Mahon was an 'ordinary agricultural labourer' living at 1 Billington Court off Lewin Street. He was unmarried and aged 28 years. This would make him 41 years old when he reenlisted (although his Service Record indicates that he stated his age as 38 and his home address as now on the Holmes Chapel Road.). He was 42 years old at the time he was killed – which was quite old for a soldier in the First World War. The 1911 Census shows that he was still a farm labourer.

By the end of the fighting for Hill 60 casualties of 5th Division (including those of 1st Cheshires) amounted to more than 100 officers and 3,000 men. Probably about one third of these men were killed. The total casualty figure for 1st Cheshires alone is not recorded in the Battalion War Diary as far as I can see. German casualties are unknown but were probably of a similar magnitude to those of the British. Officially, the action on and in front of Hill 60 in 1915 was not counted as a “battle” and therefore it does not appear on the colours of any of the regiments that were involved.

When Hill 60 is remembered today it is usually for the explosion of a huge mine there over two years later in 1917 - one of 19 detonated simultaneously to drive the German army off the Messines ridge. The action of 1915 is often overlooked - as indeed it was by most of the newspapers at the time. The tragic events of Hill 60 were overshadowed by what was happening on a larger geographical scale elsewhere in the north and east of the Ypres salient and in the Dardanelles. Coincidentally the Cheshire Regiment was also involved in this latter disastrous campaign and sustained more heavy casualties.

Peter Crook,

November 2020

Article by Peter Crook