Guillemont, 3 September 1916 Tactics and Insights

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Guillemont, 3 September 1916 Tactics and Insights

‘Not a Single Blade of Grass...’ by Sebastian Laudan

[This article first appeared in Stand To! No.106 July 2016 Special Edition].

In 1926 Oberstleutnant aD (Lieutenant Colonel, retired) Wilhelm Nau published the last volume of a series of books covering the participation of the infantry regiment he had been serving with in Belgium and France throughout the first two years of the war, namely Infanterie Regiment ‘Hamburg’ Nr. 76 (IR 76). In preparing his books for publication Nau - who held the rank of major during the war - used the diaries he had kept throughout the conflict and enriched his works with many comments, hand-drawn sketches and detailed maps. Here Sebastian Laudan reveals Nau’s recollections of the German struggle to defend Guillemont in the face of the British onslaught in the late summer of 1916.

Author’s note: All time designations are referred to as German time (ie GMT+1).

Soldier: "Herr Leutnant, where is Guillemont, I can’t see it!?"

Officer: "Hold on, I'll point it out to you. Look at the [shell] impact and the black earth rising - that is open field. Now see that impact followed by red dust rising - that is Guillemont, there you are!"(1)

‘About August 21 (the 111th Division) was relieved and sent to the north of the Somme. Engaged near Guillemont and Guinchy (sic), it suffered serious losses (Aug. 25 - Sept. 6).’(2)

New Division

At the outbreak of war in 1914 Wilhelm Nau had been in command of II (Bataillon) IR 76 (II/IR 76) and led his men among the bulk of von Kluck’s First Army into Belgium and France. He directed his battalion through the raging battles of Mons and the Marne and took up a position between the rivers Aisne and Oise during the winter of 1914/15, only to see his regiment being transferred to the newly-formed Prussian 111th lnfanterie-Division in March 1915. The three lately combined North German infantry regiments, IR 76 from Hanseatic Hamburg, Hanoverian Füsilier-Regiment 73 (FR 73) in addition to IR 164 from the Weser Uplands, were to suffer heavily in spring 1915 while defending a sector of the notorious St Mihiel Salient against the French. Relieved from this region in August 1915, the 111th Division moved far to the north and took over the relatively ‘calm’ front line sector around Monchy-au-Bois and Ransart south of Arras. Not before the end of August 1916 was the division to become seriously engaged again, this time in the epic Battle of the Somme, raging a little way to the south.

Eager to Learn

The unit found itself pitched up in the vicinity of what was the already hotly-contested village of Guillemont. It was here, on the decisive day of 3 September 1916, that Major Nau was wounded and fell into British hands. He remained a captive in a British prisoner of war camp for the duration of hostilities and developed a profound interest in the preparation, execution and ramifications of that remarkable day of battle, a day which had effectively ended his military career.

Nau had kept a meticulous diary from the outbreak of the war. As an officer in captivity - almost certainly fighting boredom and emotional trauma - he was eager to learn, in detail, how the British had managed to overrun the German lines at Guillemont - albeit not at Ginchy - in such a rush. At an early stage Nau began to enrich and amplify his own notes by interviewing many comrades during his incarceration and continued to do so after the war. Later he consulted the Potsdam Reichsarchiv, housing the Prussian military archives, and even purchased a copy of the standard British History of the Twentieth (Light) Division by Captain Inglefield. After having completed the picture Nau was able to tell a more balanced story of the fight. In his personal conclusion he refers to 3 September 1916 - for him a remarkable day of battle - as being at once a brilliant feat of arms and a day of tragedy.

The Somme - late August 1916

In February 1916 it was the Germans who opened up a year of incredible carnage by attacking the iconic town of Verdun. It was their first major offensive on the Western Front following Second Ypres in April 1915 and actually was to be their last prior to March 1918. Surprised by a large-scale Russian offensive in the east, by early June 1916, Germany was forced to send reinforcements to prevent her Austro-Hungarian ally from collapsing. It was then that the Entente forces in the west - following a concerted overall strategy - attacked astride the River Somme in Picardy and thus embarked on an ambitious campaign that was to burden military history with a sombre legacy.

After a preliminary bombardment unprecedented in its duration and intensity, followed by a disastrous prelude in the northern sectors of the battlefield - particularly astride the River Ancre, the British managed to exploit success in the south and gradually pushed the Germans back towards the strategically important town of Bapaume. The losses were enormous on both sides. From mid-July onward, and throughout August 1916, the British Army clawed its way across fields, through villages and woods and over ridges whose names and reputations live in infamy to this day. The tactically important village of Guillemont had already been attacked several times - and had even been entered on 30 July, 8 and 18 August - but was never secured, so by the end of that month it was still in German hands. However, the defenders had also lost heavily. Reserves were limited, and the British knew it, hence they calculated that another ‘last push’ would win the battle, threaten Combles and help secure a line from which they could assault the third German position barring the way to Flers.

By 1 September 1916 then, the southern flank of the British Army was stalled in front of the rubble heaps of Guillemont and Ginchy, both serious breakwaters against the incoming tide and blocking the roads to the small town of Combles, the very hub of the German defence system of the entire sector.

‘Maze of Trenches, Saps, Strongholds’

Guillemont and Ginchy had both been typical rural Picardy villages in what had been the relatively undisturbed hinterland of the Somme front but by the end of August and early September both villages had ceased to exist, each having received its share of massive bombardments. The villages were discernible only by flat heaps of rubble and reddish (some say whitish) dust: the wasted landscape all around being shell-tom and desolate.

In late August 1916 it was up to the German 111th Division, a fresh and very reliable unit in terms of Western Front standards to play a role in the large-scale battle between the Somme and Ancre rivers.

On 23 August IR 76 entered the ghastly front line at Guillemont. 111/76 was sent straight into the firing line, while 11/76 under Major Nau was to man the rear position:

‘We remained in billets [at Etricourt] until late afternoon. In Le Mesnil I met Major von Burstin [CO IR 76] and received orders for the deployment of the battalion. We were to man the second and third line at Guillemont. More information was obtained by Hauptmann Prausnitzer, who was with the Generalstab [General Staff] of our Division. He passed on trench maps left behind by our Württemberg predecessors, showing the well-built village of Guillemont and an impressive maze o f trenches, saps and strongholds. Everything looked really fine on the map,just like our previous position at Ransart. If only the trenches were still there... I was asked by the CO to relay a comment on the actual state of the position after having reached it. A couple o f days later I got hold of an aerial photo showing our position at Guillemont, a literal moonscape, without any traces of buildings, roads or even the railway left.

‘By 9.00pm we decamped, me leading the battalion, accompanied by my staff and a liaison officer of Wurttemberg IR 120. In Sailly we made a halt at a Pionierdepot [engineer’s depot] and picked up our newest armour, the Stahlhelm [model 1916 steel helmet]. By nightfall we were approaching a village presumed to be Morval, instead found ourselves in Combles. Actually we had got lost and were forced to walk in complete darkness across a craterfield northbound towards what was once the road Morval-Guillemont. A sift hat weren’t enough, we ran into an artillery battery, which we hadn't noticed until the gunners suddenly opened up a deafening fire. Finally my old compas led us to our objective. The companies followed right behind, the men were puffing and blowing from the loads they had picked up at Sailly: provisions, water, hand grenades, picks, shovels and even timber. During the night we relieved our Wurttemberg comrades-in-arms, who obviously were eager to get away. They told us in their weird Swabian dialect of a recent English attack, which had been repulsed by our III Battalion, namely the marvelous 9th Company.

‘The next day I was visiting our second line running along a low ridge that stretches from Ginchy to Leuze Wood. At the spot where the elevation crosses the railway bank, forming a sunken road of about three metres depth, some shallow dugouts had been driven into the embankment. This was now our Bataillonsstab [Battalion HQ]. We and the artillery observers had an excellent viewfar across the country. According to the trench map, Guillemont should be seen by following the railway cutting for a few hundred yards, but there was nothing except a speck of red dust. Ginchy could be picked out only by the remains of a single rooftop! Near the railway cutting narrow trenches had been dug to the left and right, barely able to cover a man standing upright. The men were lying there without any protection against the weather and the shells. We started digging and deepening trenches. At least the third line provided some shelter we could use.

‘In the afternoon the [British] artillery fire rose and by dusk became a veritable Trommelfeuer [drumfire]. Battalion Hiibner (111/76), over there in the front, was totally covered in smoke, yellow dust and bursting shells, while aeroplanes were circling over their heads. We were watching the scene with awe through our binoculars and suddenly noticed fading red flare lights - Sperrfeuer [defensive barrage fire]! I ran to the nearby artillery observation officer and told him to pass on the request. He lectured me as to the importance of saving ammunition but I told him sternly to act immediately and had my men fire red flares as well.

‘The next day, 25 August, was rather quiet in our sector, however, our neighbours were kept busy all day. In the afternoon we faced the same situation as the day before, the smoke screen, red flares, our Sperrfeuer setting in. Around 10.00pm the enemy sfire faded away and finally ceased. During the night we were shifting duties, I Battalion went into the frontline, III Battalion, completely exhausted, took over our reserve position, we were to go back. Getting to the rear relatively safely meant moving along the railway cutting and then further along the shell-pocked Ginchy - Morval road. Easier said than done by night and under fire, it was not until dawn the following day that we were able to erect our tents in the northeastern corner o f the enormous, yet tattered, St Pierre-Vaast Wood.

‘Actually we had come from smoke to smother. It was raining permanently and many men suffered from bowel disease. By nightfall the enemy shelled the woods with long-range random artillery fire which made it hard to find secure spots. In the end the companies had to scatter all over the place in order to prevent losses from direct impacts. Nevertheless, the battalion lost two men killed and several others wounded. I heard my men saying: "If only the English infantry was coming, but these stray shells... ”

‘The following days were painful, the humidity, the poor accommodation in tents standing on mud, the artillery fire preventing any repose. As soon as the sun dared to come out for a quick peek, English aeroplanes were circling the sky, observing, even spreading pamphlets gloatingly indicating Romania’s entry into the war.

‘On 29 August we were about to relieve I Battalion in the front line, but not without a farewell from the weather god, who sent a thunderstorm, leaving us soaked to the bone. Without the slightest regret we pulled down our floating camp and left the inhospitable wood behind.

‘By nightfall the companies were advancing.

In Sailly provisions and water were picked up, then the path led us back to the front, yet again via Morval and the notorious railway cutting through the rear lines which we had been holding four days earlier. Covered in sludge I reported to the regimental CO, Major von Burstin, who I wouldn't see again before the end of the war and captivity. ... Before I left I shook hands with another fellow officer, Leutnant Hiibner, who told me o f the hell called Guillemont and dismissed me with the words: “Well, dear Nau, when the English finally attack for real, we’ll be done. ”

‘The next day, 30 August, 11/76 was still held back in the second and third lines o f the regimental sector. The day was calmly ticking away, it was drizzling. Wemade;thebestofitby checking our equipment and providing the men with whatever material and provisions were available. By dawn the next day, 1 September, it was up to us to man the frontline, so we began to relieve the companies of I Battalion, which lasted all day until the evening. ’

Not one brick remained

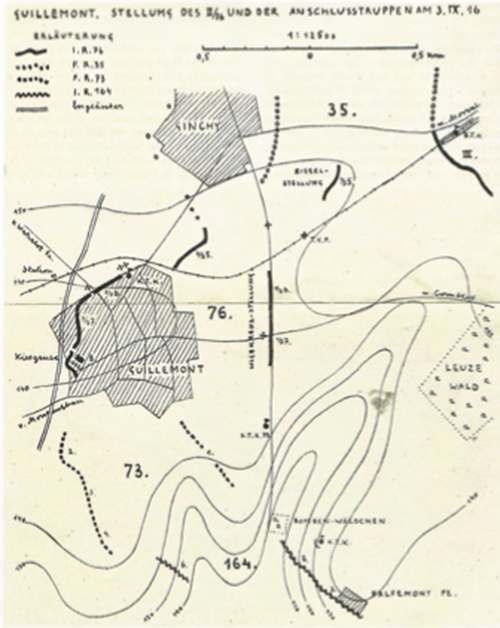

Nau describes, with reference to his own sketches, that the position of IR 76 roughly followed the western edge of Guillemont. The sector was bounded to the north by the intersection of the Ginchy road with the Morval - Montauban railway, to the south it was limited by the Montauban road.

To the immediate right of I R76 stood Fusilier- Regiment 35 (FR 35) of the Brandenburg 5th Division, with only few advanced posts west of Ginchy and its main body just east of it. The left (southwestern) flank of Guillemont was covered - although not along its entire length - by the Hanoverian Fusilier-Regiment 73 (FR 73), among whose ranks served a talented, although not yet prominent, junior officer - Leutnant Ernst Jünger.(3)

Even further south, the third regiment of the 111th Division, IR 164, held the Falfemont Farm compound and guarded the ground in front, covering the valley that ran northeast from the village of Hardecourt-aux-Bois towards Leuze Wood.

By now the terrain bore virtually no discernible landmarks: the ground pitted with shell craters of all sizes. From afar the village contour could only be recognised by reddish brick and tile dust as well as a few mutilated tree stumps. No village streets, no country roads existed, even the line of the railway had been shelled so comprehensively that it was barely distinguishable, except from the air. Ernst Jünger confirms this observation: ‘When morning paled, the strange surroundings gradually revealed themselves to our disbelieving eyes. The defile proved to be little more than a series of enormous craters full of pieces of uniform, weapons and dead bodies; the country around, sofar as the eye could see, had been completely ploughed by heavy shells. Not a single blade o f grass showed itself. The churned-up field was gruesome... The village of Guillemont seemed to have disappeared without trace; just a whitish (sic) stain on the cratered field indicated where one of the limestone houses had been pulverised.

And yet another source, namely the British 5th divisional history, reaffirms the surreal state of the scenery: ‘...Guillemont... as a village no longer existed; infact, except for the marking on the map, it would have been impossible to tell that that shell-pitted expanse of ground had ever been a peaceful agricultural hamlet. Not one brick remained.’

To the troops coming in from Morval, a single head-high tree stump at the northeast corner of the village served as the only, yet most welcome, orientation aid. Everything still connected to Guillemont had gone underground: wells, caves, fundamentals and hollows. Nau, in his post-capture inquiries, interviewed several survivors who confirmed that single men and even small parties had been hiding in these village cavities, invisible from the surface, before and during the attack and had stood their ground before being killed or captured.

Hapless

At the northwestern edge of Guillemont a shallow depression, no more than 21m difference in altitude, dropped away towards the first British line about 75m away. This slightly elevated ground was held by 6/ and parts of 7/ Kompanie IR 76 (7/76), while the remainder of 7/76 and 8/76 were holding the western and southwestern edge of the village. This latter position was dominated by a fortified Kiesgrube (The Quarries) about 5m in depth and no more than 20m from the British. Accessibility to and from the Kiesgrube was impossible during the day and extremely difficult by night. Even compasses proved untrustworthy as there was too much ‘iron’ lying around. Considerable detours and wrong turns were commonplace among patrols and supply parties. The situation had already led to an annoying situation a few days previously, when the OC of 4/76 missed the German firing line during a relief between I and III Battalions, advanced alone into no man’s land and was captured. Although the incident caused no more than the loss of a single hapless junior officer, the British Army bulletin of 26 August mentioned the German ‘attack’ northwest of Guillemont, which had been ‘beaten back'.

Leutnant Jünger describes a comparable situation, while holding the sunken track opposite Arrow Head Copse: ‘At dusk, two members of a British ration party lost their way, and blundered up to the sector of the line that was held by the first platoon. They approached perfectly serenely... [and] were shot down at point-blank range...It was hardly possible to take prisoners in this inferno, and how could we have brought them back through the barrage in any case? ’

The second German line, the Reservestellung, was in no better shape nothing, was left of the trenches and strongholds visible on the trench maps. Every night shell craters became roughly connected to each other to form a trench which was barely head-height and of dubious value. There were no further obstacles available, no barbed wire, no barriers, nothing to prevent an enemy from driving through, given that the pocked, iron-studded ground was hazardous and rough at any time to both attacker and defender.

The second German line, the Reservestellung, was in no better shape nothing, was left of the trenches and strongholds visible on the trench maps. Every night shell craters became roughly connected to each other to form a trench which was barely head-height and of dubious value. There were no further obstacles available, no barbed wire, no barriers, nothing to prevent an enemy from driving through, given that the pocked, iron-studded ground was hazardous and rough at any time to both attacker and defender.

When Guillemont itself had become part of the front line, the Germans had hastily driven several mineshaft-like Stollen into the earth, which proved their worth against shrapnel and shell fragments. Prior to 3 September no such excavation seemed to have been smashed, however, some of these dugouts turned out to be death-traps as a result of the noxious gases emitted by exploding high explosive shells. One such tragic incident took place on the eve of 3 September, when a dugout held by a half-platoon of 6/76 became buried by a single, huge shell. After having removed the rubble a brave Sanitater [stretcher-bearer] crawled into the shaft with the help of a breathing apparatus, only to find his twenty-five comrades dead; all physically unhurt, and looking like men asleep.

The Kiesgrube (Quarry) of Guillemont in August 1916. The quality is poor but is included here as images of the Kiesgrube position and its garrison are rare.

Communications

Apart from the absence of a continuous front line, ensuring communication was the key problem. Liaison with the artillery and the staff behind was delivered by Meldeganger [despatch runners] only, as no technical means were available. Permanent artillery fire prevented the layout and maintenance of telephone cables, the sole existing earthbound connection had been destroyed long ago and could never be re-laid prior to 3 September. II Battalion’s Blinker-Trupp [light signalling unit] tried in vain to establish some sort of communication with the rear, only to draw hostile fire at once, leaving both crew members killed on the spot.

Weather conditions were uncharacteristic for late August: heavy rain - the worst downpour on 29 August left trenches and craters full of water - then calm autumnal weather from 31 August on. Sunday, 3 September, began hazy before the sun came through, so visibility on that day should have been perfect. Thanks to a light wind, the usual smoke and dust caused by heavy artillery fire on a Grosskampftag (main battle day) wasn’t as heavy as on 24 August.

Before the Attack

According to Nau, the men defending Guillemont were grimly determined to fight despite the miserable conditions they were vegetating in. They at least felt themselves fairly well equipped: all unwieldy Tornister (haversacks) had been left behind and replaced by an improvised, though convenient version, simply made of sand bags and straps sewn together, designed to carry everything from hand grenades to provisions. By autumn 1916 almost every soldier in the frontline wore the new steel helmet, and this held true at Guillemont, too. The few who hadn’t been able to fetch a steel helmet were quickly offered one of those lying around in abundance on the battlefield.

Rifle and machine gun ammunition was given out in sufficient amounts, although hand-grenades were short. Each company was supplied with four flare guns and plenty of Very lights.

In the reserve position food supply had been good, thanks to the field kitchens daring to get as close as possible. When ordered to occupy the very frontline on 1 September, 11/76 was provided with iron rations only, each consisting of one portion of Zwieback (hardtack), canned meat and a bottle of mineral water per day, hence four packs for the scheduled four days in the trenches. Any other supply was left to the Trägertrupps (supply carriers), which were to try their luck by night, usually forty men of each company. Of course this sort of nightly traffic drew fire of all sorts from the enemy and caused severe losses: one carrier party of 8/76 left Guillemont with twenty men, of which only two came back at all.

Medical services were provided by the two battalion surgeons, one manning the Truppen- Verbandsplatz (TVP), the advanced dressing station at the railway embankment, while the other stayed within the third line. It was extremely difficult for the Sanitater to carry back the wounded, if anything then by night only. This was made even worse by the fact that in the beginning no stretchers had been available and only few reached the forward lines at all.

Since II/76 had taken over Guillemont on Friday, 1 September, all hands were looking forward eagerly to detect any discernible signs of an imminent attack. Of the British infantry in the trenches not a single move could be seen. The next day, 2 September, Leutnant Hennings demanded pinpoint fire against what seemed to be a troop of British sappers coming out of Trones Wood as if there was no war. Blimps were soaring into the air, fourteen of them could be counted, a certain sign of the menace looming ahead.

By early morning of Sunday, 3 September, British troops could be seen pouring out of Trones Wood and heading undisturbed at a leisurely pace for Waterlot Farm, again without an appropriate reaction by the German artillery.

The British artillery had been busy throughout the days before, however, the intensity of the bombardment varied between rather heavy to patchy, more acute during the day, fading away by nightfall. Not only trenches and strongholds had been targeted but also all approach roads and concentration areas behind the German front had received attention too. The Ginchy - Guillemont road and the southwest corner of the latter especially was severely battered, although not with gas shells.

The artillery fire was mainly directed by British aeroplanes circling above the German lines from dawn till dusk. Some pilots flew daringly low, strafing the trenches with rather ineffective machine-gun fire, and were sometimes greeted in kind by their potential targets.

Although the British tried to obscure their intentions, the Germans knew very well that a massive blow was looming. 11/76 had tried desperately to consolidate the fragile position and to close the gaps between its own companies and those of its neighbouring units to both flanks, but to little avail. The most dangerous breaches in the front line were to be found between 8/76 and I/FR 73 southwest of Guillemont and further along towards the affiliate IR 164. The latter gap had already been widened in mid-August - the position was then still in the hands of a Württemberg regiment - and had never been plugged.

Sanddüne

Major Nau harboured no illusions with regard to the baffling scenario in front of him: the German position lacked not just a continuous line but in places it had begun to disappear completely. He described the terrain as looking more like a ‘Sanddüne’ [sand dune], shifting back and forth, pierced by strings of foxholes and dugout entrances. As everything visible on the ground became smashed, sooner or later all men and material had burrowed as deeply as possible into the earth - mostly at night. The outcome of all nocturnal activities could be seen by dawn and made the battered stretch of land appear as if it was constantly in motion. The scenery changed from day to day and no aerial photograph, let alone a trench map, could reflect the current situation. This, besides British aerial dominance, made it quite impossible for the German artillery to provide accurate fire, while an adequate supply of men and material to and from the fighting line was almost unmanageable. It was but cold comfort to the Germans that the British artillery too lacked discernible targets and had to scatter its fire randomly over the entire area. In the end, the tactically important Kiesgrube - which naturally had become a prime target for the British artillery - remained the only recognised stronghold in the entire German line.

German Agonies

Astonishingly, the Germans incurred fewer fatal losses to the random bombardment than one might expect. Many men, if not killed immediately, suffered more or less seriously from bleeding wounds or blunt force trauma, being hit by small shell splinters, stone fragments or lumps of earth. As a rule, men buried alive while hiding in shallow foxholes had a far better chance of survival following a close impact than others being stuck in deep dugouts, however, this didn’t help in the case of a direct hit. In any case all troops at Guillemont were ordered to seek shelter under canvas in stray foxholes or shell craters and remain still during daylight. In some places the men even advanced and hid as close as possible to the British first line, in the hope that hostile fire would pass over them.

To give an example of the agonising conditions the men at Guillemont were facing, one only has to consider the fate of the highly regarded Leutnant Naeve, in command of 5/76, north of the village. At around 8.00am on 2 September the officer was severely wounded when hit by fragments of a heavy shell in the left leg and became buried at the same time. His two companions were killed outright. A party of men hurried out from a shell crater nearby and unearthed the officer before he suffocated. The Leutnant was alive, but barely so, his chest and lungs squashed, hardly able to breathe, his left leg ripped open and bleeding heavily. Moreover, the forward rim of his steel helmet, his lower lip and chin had been split cleanly by a shell splinter from above. Although the Leutnant was severely wounded, he had to wait all day sitting upright and barely conscious in a shell hole, his wounds dressed cursorily, before being taken back at night just like any other injured man.

Despite the conditions, officers and NCOs were trying desperately to maintain a minimum of combat-readiness. During the long hours of daylight communication was almost impossible between leaders and troops beyond that of shouting distance. Everyone was under canvas, lying down motionless to prevent being noticed by enemy planes or artillery observers. Hence the men became listless and rigid, only hoping for an enemy attack to be delivered of the misery either way.

By nightfall the men became alive again and their duties were legion: rescue of the wounded, distributing supplies, the salvage and overhaul o f ordnance, the rebuilding of damaged or levelled positions.

Night patrols were sent out to reconnoitre no man’s land and the British positions always got lost somehow, as there were no landmarks or topographic features left for orientation. During the night of 2 September a patrol consisting of an officer and three men scouted towards the British position and seemingly succeeded in doing so, approaching very close until they could start eavesdropping. It was not until the ‘English’ began to whisper in German that the patrol realised it had crawled north in a semicircle and had finally bumped up against a picket-guard of FR 35 near Ginchy! Fortunately the patrol was able to withdraw as silently as it had approached. Major Nau finally ordered his company commanders to prohibit all patrolling by night as this would only lead to even more confusion and false alarms or worse. It may be said that a German front line worth the name did not exist prior to 3 September. There was no working system of coordinated defence, no communication or supply, only the anticipation of a major attack, which, and this had been clear to all defenders, would, in all probability, be devastating.

The Night Before

Nau states in his diary that by nightfall of 2 September morale was generally fairly good, even given the unbearable conditions. Although most men were wounded to a greater or lesser extent or were at least mentally traumatised, they wanted ‘pay back’. More importantly, all machine guns were still intact. 7/ and 8/76 had only few fatal losses to declare, while 6/76 mourned the above mentioned annihilation of a half platoon as a result of the dugout suffocation incident. 5/76 had suffered from the almost complete levelling of its ‘desert-like’ position between Guillemont and Ginchy and along the railway embankment and was completely exposed to shells and advancing infantry.

Lessons learned by the Germans were that there was no demand for reinforcements from the front, as any additional movement by day and night would lead to more hostile artillery activity resulting in even more casualties. Moreover, it was up to the reserves to hold the second and third lines in case of a British breakthrough or to counter-attack if possible. This fatalistic but resolute attitude from the men in the front line was regarded with both admiration and concern by Major Nau, as the forward unit’s combat strength had been drastically reduced within the previous 48 hours. The physical condition of the men was alarming, considering the fact that everybody was exhausted and had been short of food and drink for three consecutive days in spite of the short stay in St Pierre-Vaast Wood which, to put it mildly, had not been ‘comfortable’.

At sunset on 2 September, the German position came back to life as there was plenty of work to do which could not have been done in daylight. Volunteers were countless, happy to move and act again like human beings. Major Nau made a very last report to his regimental CO and declared that the situation was 'rather difficult’, but that the men’s confidence remained ‘unbroken’.

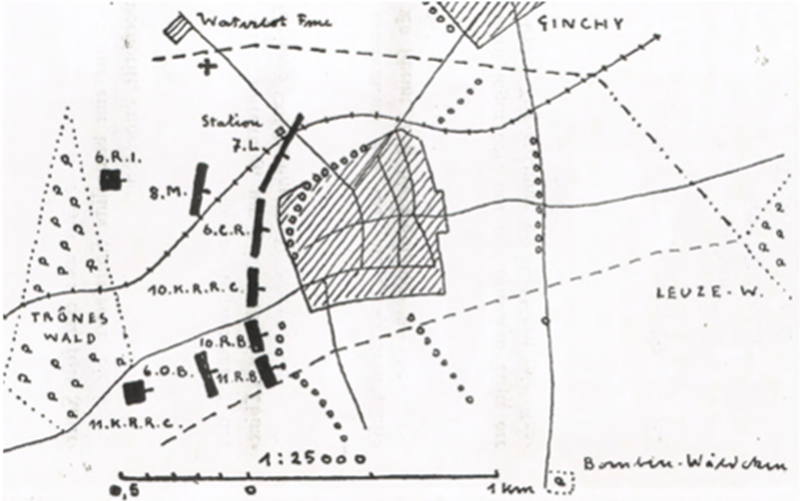

Assailants

Opposite the German defenders stood the British 20th (Light) Division, a new Kitchener’s Army division raised in September 1914. In France since July 1915, the division had not taken part in any of the major battles of that year and although having had its share in the fight for Mount Sorrel near Ypres in June 1916, still lacked experience in a major battle. By the end of July 1916 the division was sent to the Somme, only to be handed the ‘appalling’ - according to Inglefield - sector between Beaumont-Hamel and Hebuteme. By pure coincidence the Prussian 111th Division, had then held a position within a stone’s throw further north. Now the two divisions were to be pitched against each other at Guillemont.

By 22 August the 20th Division had relieved the worn-out 24th in the sector roughly bounded by the Montauban - Guillemont road and the southeast corner of Delville Wood. Almost as soon as it had taken over, the division was ordered to prepare for a general attack which would be carried out on 24 August all along the British Fourth Army front in conjunction with the French. However, after nightfall on 23 August -according to Inglefield - unexpected artillery fire as well as a minor German sortie by III/76 out of Guillemont made further preparations impossible. The British were forced to postpone the main attack and rescheduled it for 29 August, then for the following day and finally set it for 3 September due to a combination of bad weather, repeated German infantry and artillery activity and the general exhaustion of the troops, who had been digging, building and carrying for days and nights. Inglefield refers to the high morale and combat readiness among the men in spite of the constant attrition - the British 59 Brigade alone, having been in line for nine days, had lost 600 men before being relieved by 61 Brigade.

This constant ‘nibbling’ and draining of British manpower, had led to a rather risky regrouping of the units deployed to take Guillemont proper: 60 Brigade had been so undermanned, counting no more than 1,550 rifles, that it had to be regarded as unfit for attack. Thus on 1 September 47 Brigade of the 16th (Irish) Division was deployed to the 20th Division in order to form the first wave of attack along with 59 Brigade (reinforced by 6/Ox and Bucks Light Infantry of 60 Brigade), while 60 and 61 Brigades were to remain in reserve. Nau saw some of the Irishmen after his capture, and described them as ‘young folks, offering a fresh appearance, and, due to their seemingly brand-new attire, could be regarded as just recently committed to the front.'

59 Brigade was put back into the line during the night of 2/3 September. Inglefield remarks that the days of rest, the mild weather and some good food had served the men well and put them in an excellent mood. Moreover, the Germans were obviously saving their shell stock, hence artillery activity was low and no gas shells had been used. However, many aspects of the original plan of attack had to be reconsidered by corps and division at short notice, quite a challenge according to Inglefield: ‘In spite of these changes [to the original operation orders] such a short time before the attack, all the necessary arrangements were made and worked well during the battle.

Ratio

Within the attack sector of the 20th Division the balance of power was far from even. The British 47 Brigade (2,400 rifles) and the reinforced 59 Brigade (2,300 rifles), could deploy some nine battalions by noon on 3 September to face one and a half German battalions (11/76 plus about half of I/FR 73) - though in name only. Even this imbalance did not reflect the actual picture, as only two out of six German companies (2/73 and 8/76) involved were holding the line in its entirety, the others had no more than two of its three platoons present in the frontline.(4)

A regular German company consisted of three Züge (platoons), each counting for about eighty rifles, plus the small Kompaniestab (company staff). Nau assumes (and defends his figures by relating them to the known casualties after the battle) that no more than some sixty rifles per platoon were available. So, on 3 September fourteen German platoons were facing two British brigades in the first line, with four to five more platoons holding the second line at the Riegel-Stellung near the railway, the Wegekreuz-Stellung and further south up to the Bomben-Wäldchen (Wedge Wood) respectively, some 1,000 rifles in total. So, in rough numbers only, the ratio was about 5:1 in favour of the British.

Besides the obvious superiority in numbers and firepower, morale and discipline must have been excellent among the British. Nau quotes the observation of a German survivor that ‘the troops [6/Connaught Rangers] attacking the Kiesgrube seemed to be ‘feuerfest’ [bullet-proof] and had carried on stubbornly regardless of losses.’

Nau was even able to sneak a glimpse at the British artillery after his capture: ‘The English artillery consisted of the divisional artillery of the 6th and 24th Divisions as well as the heavy artillery of XIV Army Corps. Apart of this artillery I could watch while being carried wounded from the battlefield on the afternoon of 3 September. It was placed in two elongated lines between Trones and Bernafay Woods, about 1,200 to 1,300 meters behind the English Jump-off line, wheel-to-wheel, each gun separated by a sackcloth, masked against aerial view. I saw the gunners eating, firing, getting shaved and carrying ammunition. After the battle I read a newspaper article written by an Irish officer with regard to the very same artillery position: “The guns stood so close to each other, they seemed to be touching, they were firing constantly, and several Irishmen standing around began to wonder whether there was anything still alive within the German lines. ”So sorry that our few planes hadn’t been able to spot this worthwhile target, whose annihilation might have changed the outcome of battle.’

Nau also witnessed the effect of his own artillery and was disheartened: ‘The area east of Trones Wood received only stray heavy shellfire. Field artillery would have caused havoc among the ubiquitous English infantry. West of Trones Wood only few shrapnel [shells] could be seen at all, while west of Bernafay Wood total peace was reigning.'

This observation stood in contradiction to Inglefield’s description of heavy losses caused by German artillery, especially among the reserve units. An indicator of how deficient the German artillery really was might be the fact that, again according to Inglefield, British subterranean communication lines between divisional and brigade HQs were relatively undisturbed. By contrast communication within and among the German positions was almost non-existent before and during the attack. Apart from a few dispatch runners and vaguely visible flares, no other communication was available to the Germans.

Attack

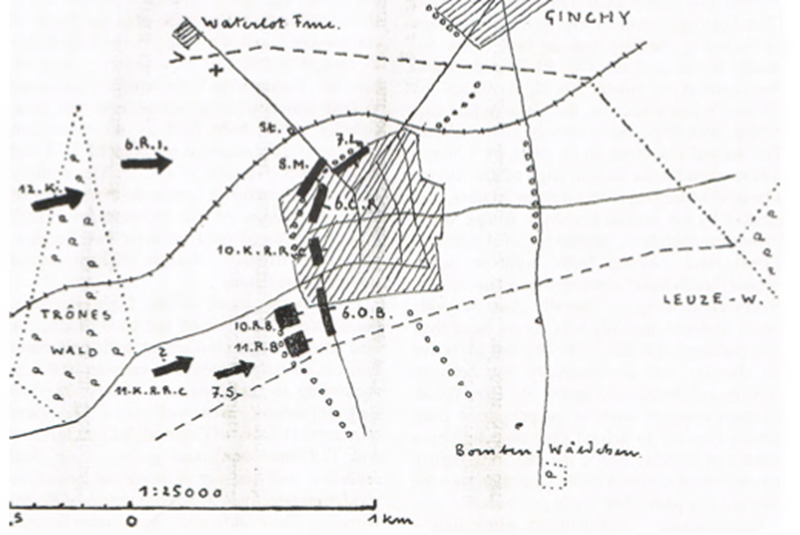

The original British plan had been to attack Guillemont simultaneously in an enveloping movement from the south, west and north respectively. Although the German front north of Guillemont and further towards Ginchy was only sparsely occupied, the British regarded this area with mistrust, presuming enemy reserves and field guns waiting in hidden folds behind. On the other hand the German line at the southwestern edge of Guillemont and along the two barely recognisable sunken roads seemed just thinly held. Only the Kiesgrube (The Quarries) might cause serious problems by bringing flanking fire to bear from the south. In the end the OC 59 Brigade made the decision to bolster his right flank. The division’s first objective, the German first line proper, was to be taken shortly after 1.00pm. The second objective, to be taken by 1.50pm, was marked by the eastern edge of the village. The third objective, to be taken by 3.00pm, was marked by the sunken Ginchy - Wedge Wood (‘Bombenwäldchen’, northwest of Falfemont Farm) road running from north to south behind Guillemont cemetery and the crucial Wegekreuzstelhing - literally the Wayside Cross Redoubt, actually held by no more than two platoons of 6 and 7/76. The last objective for the day was an imaginary line between Ginchy and the western comer of Leuze Wood. German reserves were to be prevented from getting forward to defend each objective by a curtain of shellfire, while the attacking British waves would follow a rolling barrage, moving forward at a pace of 50 yards per minute.

Nau remarks - not without admiration - that this plan actually proceeded astonishingly well, at least until the third objective had been reached when German reserves and artillery did come into play.

According to Inglefield the British artillery fire began by dawn on Sunday, 3 September 1916, and by 9.15am a ‘Chinese Attack’ - a feint attack - was announced by concentrating heavy fire on the German forward lines. Nau describes that 8/76 at the key Kiesgrube position came in for extra attention, to no one’s surprise, and lost three out of four heavy machine guns - apparently having been placed too close together - due to a single heavy shell strike. At 9.30am the area northeast of Guillemont - called a ‘trap’ by the British due to several recent bad experiences - was hit hard too. It seemed as if the attackers presumed to find strong German reserves in that area: actually it had been held by no more than two completely exposed platoons of 5/76 and isolated picket-guards of FR 35. The artillery preparation reached a crescendo at the hour of attack - 1.00pm. At that moment the British infantry followed hard on their own barrage, advancing frontally, though slightly curved inward at the flanks.

Prior to the attack of the Light Division, the adjacent 5th Division had tried to take the area southwest of Guillemont with Falfemont Farm as its main objective as early as 10.00am. According to the divisional history ‘the [95 Brigade] advance went well ...and, two hours after zero, [1/Duke of Cornwall’s Light Infantry and 12/Gloucesters] had gained their final objective, and had dug in along the line of the road from Ginchy to Maurepas, north of Wedge Wood... Their advance was magnificently executed, and, in spite of a withering machine-gunfire, the line never wavered for an instant; but both Battalions suffered considerable losses... ’ The history of FR 73 confirms the vigorous capture of the Hanoverian position (3 and 4/FR 73) and bewails the extermination of the entire garrison. However, 95 Brigade was impeded due to the constant flanking fire from Falfemont Farm, where 13 Brigade had been pinned down and remained so. Following an impressive advance of 3,500m, the designated line between the southeast corner of Guillemont and the Bombenwäldchen could finally be reached and secured, but the brigade’s right flank stayed in limbo and remained so for two more days.

Sunken Lanes

The front line trench held by the whole of the 2nd Kompanie and parts of 3rd Kompanie of the Hanoverians southwest of Guillemont formed a sharp angle, with its tip pointing to nearby Arrow Head Copse. The position’s upper line ran parallel to a (‘western’ or ‘first’) sunken lane just ahead, which branched off in a southwestern direction from the Guillemont - Montauban road and led further on toward what the British had dubbed Maltz Horn Farm. The angle’s lower line ran back towards another sunken lane about 150m to 200m behind the first. This (‘eastern’ or ‘second’) sunken road, serving as a back-up, ran due south until it hit the Guillemont - Hardecourt road.

Shortly after 1.00pm I/FR 73 was hit by two Rifle Brigade (RB) battalions of 59 Brigade (10/RB, 11/RB), which were then leapfrogged by 6/Ox and Bucks, the latter taking the ‘eastern’ sunken road by 1.30pm. The outnumbered Hanoverians offered stem resistance - no quarter was given - but were eventually overrun and not a single man of 3/FR 73 was left alive to tell the story: the company simply vanished. Almost the same fate happened to 2/FR 73 - Ernst Jünger’s company - as only a handful of survivors, albeit taken prisoner, could be counted in the aftermath.

XXX IMAGE

British gunners in Chimpanzee Valley north of Faviere Wood watching wounded and visibly distressed German prisoners passing by after the capture of Guillemont - 3 September 1916. This would have been the route most likely taken by Major Wilhelm Nau. Courtesy 1WM Q4172

Leutnant Wetje, 2/FR 73, confirmed the fact that the British had appeared in front of the ‘eastern’ sunken road by 1.30pm, while he himself was taken prisoner about half an hour later.

The action of I/FR 73 on the southwestern edge of Guillemont is particularly worth noting because the British seemed to have taken notably few prisoners in that sector, if at all, perhaps due to the fact that they had been facing rather unexpected resistance and suffered substantial losses.

Inglefield indeed confirms severe losses among the ranks of 6/Ox and Bucks - all the officers and most of the NCOs of the battalion’s three first-wave companies. 59 Brigade alone lost 1,000 men within the first hour of the attack, even though the German artillery played almost no part in the defence.

Fight for the Kiesgrube

Although Major Nau had thought the Kiesgrube a noteworthy obstacle to every attacker, it was overrun by 6/Connaught Rangers at the rush. Leutnant Hennings, 8/76, later told Nau that when the end came each of his three platoons had but ten rifles and almost no hand grenades left. The only machine gun still in order had been used with deadly force southward at a distance of no more than 200m before being silenced by a well-aimed hand grenade, while a dashing single fighter plane had strafed the ground with machine-gun fire from a height so low that it seemed to have been within one’s grasp. However, Inglefield mentions that the Irishmen, intoxicated by their rapid success, neglected to mop up the Quarries position properly, thus leaving 10/King’s Royal Rifle Corps to their immediate right in a precarious situation caused by the German flanking fire mentioned above. Yet, after no more than fifteen minutes of fighting, Leutnant Hennings and what few of his men remained were captured by the riflemen.

In this context, Nau tells a most remarkable anecdote passed on by Unterojfizier Rittmoller, 8/76, who, after the war and by sheer coincidence, came to meet the OC responsible for the capture of The Quarries, who ‘assured [him] of his proper respect for the stubborn stand the small group of defenders had made at the Kiesgrube.”

The Irish had been so swift during their advance that not only the Kiesgrube fell to them in a lightning advance but also the main part of the 7/76 position too. The Connaught Rangers must have veered to the left and rolled up the German line, as according to Leutnant Tiedt, 7/76, the enemy had come in from the rear.

In the same manner as their countrymen, 7/Leinsters climbed the low slope at the northwestern edge of Guillemont at such a pace, that the German garrison of 7/76 and two platoons 6/76 as well as the KTK (the sector HQ) staff beside the road leading to Waterlot Farm were not able to man the parapet in time, let alone bring the only machine gun into action.

At 1.50pm the British moved on toward their second objective, the eastern edge of the village or what was left about it. Again, battalions were leapfrogging others as the first waves began to secure the captured position. Some scattered Germans must have offered stiff resistance out of caves and wells, which led to some bitter hand-to-hand fighting. In the aftermath Nau interviewed one survivor, Vizefeldwebel Jakobs of 6/76, who told him of the tenacious fight within the flattened ruins that had left almost no one alive among the defenders. By 2.30pm the British had reached their second objective and were still on schedule.

There was no time to rest, however, as all ranks had to be ready to move on by 3.00pm and did so without meeting any resistance of note. 59 Brigade reached the sunken road Ginchy - Bombenwaldchen (Wedge Copse) and took the Wegekreuzstellung held by just one platoon of 7/76 under Leutnant der Reserve Brusch and, a little further north and almost touching the railway, by a platoon of 6/76 under Leutnant Brandt. This last remaining ‘thin grey line’ of about eight men could only guess at what was coming their way from Guillemont, as the entire front was shrouded in yellow smoke. Around 2.30pm Leutnant Brandt decided to advance toward the village in order to support his comrades fighting there. The brave attempt ended when, after leaving their dugout and advancing a few dozen paces, Brandt and his party ran straight into the ‘bulk of a thousand British soldiers ’, who had appeared out of the mist from south of the village. This account was confirmed later by Leutnant der Reserve Brusch, who watched two columns of British coming in from north and south of the village in a pincer movement, followed by more infantry approaching straight out of Guillemont, four battalions (6/Royal Irish, 10/ and 11/Rifle Brigade, 6/Ox and Bucks) together.

In the meantime the position between Guillemont and Ginchy had been taken by 8/Munsters, veering in from the northeastern corner of the village and thus hitting 5/76 in the flank. Both defending platoons in line counted for no more than eight to ten rifles each, the reserve platoon within the Riegelstellung between Ginchy and the railway consisted of but five men and their CO, Leutnant Schafer. By day’s end only six men of 5/76 left the battlefield unscathed and lived to fight another day.

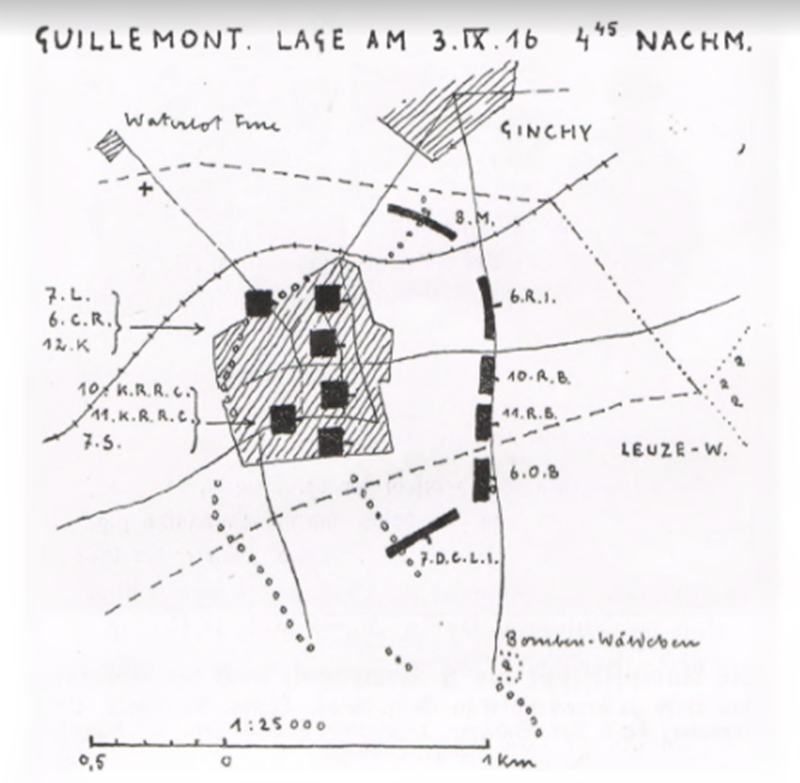

Counter-attacks

By 4.45pm the British attack had come to a standstill along the Ginchy - Wedge Wood road, with its flanking battalions, namely 8/Munsters facing Ginchy and 7/DCLI facing the copse, deployed in an outward curve in a defensive stance. The Light Division had lost any contact with its immediate neighbour: neither the British 7th nor the 5th Division had been able to keep up. Nevertheless the conquerors of Guillemont were anxious to move on. After an hour of rest, regrouping and adjustment with their artillery the British found themselves ready to advance towards the next objective, Leuze Wood. At that moment reports came in that the 7th Division had been thrown out of Ginchy again, with the 5th still held up way behind and so no further advance was possible that day. Moreover, German counter attacks and artillery salvoes began to be put in around 6.30pm, according to Inglefield - not until 9.00pm according to Nau - making it necessary for the British to stabilise their new positions and seek shelter for the night. Only probing patrols could be sent forward to ascertain what was to be expected the next morning. The following night and the next day were characterised by a period of ‘licking the wounds’, a further stabilisation of positions, the regrouping of intermingled units, aid for the wounded and the counting of losses on both sides.

Conclusion

The Battle of Guillemont was marked by several crucial components: on the British side the 20th (Light) Division, a military unit raised during the war, was assigned a task which was deemed very difficult to accomplish, possessing relatively little combat experience and forced at short notice to integrate a brigade of Irishmen the divisional commander was unfamiliar with. However, the British plan of attack was meticulously set out and executed, artillery preparation had been sufficient, weather conditions turned out to be favourable and, last but not least, the fighting morale among the comparatively fresh attacking forces seemed to be excellent. British losses were not insignificant, caused by some few tenacious nests of German resistance and one single flanking machine gun, although in the end all opposition was overcome. One has to bear in mind that all objectives for the day had been reached according to plan, a rather rare outcome throughout the war. The fact that the neighbouring divisions had not been able to keep pace, leaving the Light Division with open flanks by the end of the day and thus preventing any advance beyond the village, does not detract from the complete British victory at Guillemont.

On the German side stood the Prussian IIIth Division of fine reputation, a unit formed during the war, too, but, by 1916, consisting of long-standing, battle-hardened infantry regiments which entered the fray after a long period of duty in a rather calm sector of the Western Front. However, battlefield conditions around Guillemont defied anything that the stoic North Germans had seen thus far. In this literal desert, lacking all visible features known to a middle-European, the defender found himself under constant heavy artillery fire, erasing all means of defence as well as lines of proper communication or the adequate supply soldiers were accustomed to.

There was no permanent trench system available: no ‘pre-1 July’ dugouts driven up to 10m or more below ground level, offering protection and rest alike, until its garrison was able to man the trenches and spit fire upon the attacker, wreaking havoc. Nonetheless, Nau points out that the fundamental faith in fixed deep dugouts, drilled so far down into the earth, was regarded with ambivalence by the veterans of 1916. On the one hand such shelter could provide the only way to survive heavy bombardment over long periods and still hold a garrison ready to react in time, as had been the case along the front line of 1 July. On the other hand examples of entire groups or even platoons of men becoming trapped and being buried alive or asphyxiated deep down underground were legions. Actually many men at Guillemont, cowering in shallow holes or shell craters, became only superficially buried and were often rescued subsequently if, that is, they hadn’t been obliterated immediately away. Weighing up the pros and cons Nau offers the opinion that deeply dug shelters, linked to each other and being manned by a trained and motivated crew, was, with regard to the aforementioned inflexible 1915/16 doctrine of trench warfare and the overwhelming artillery effort, without any alternative. The tragic British casualties of 1 July 1916 obviously proved this testimony right.

As a matter of fact, the obsolete 1915 German scheme of defence at all costs, namely the written and unwritten order to hold on in the front line trenches to the last man and round, still existed in autumn 1916, although local commanders tried to circumvent it on their own initiative. Nau quoted Ludendorff, who was alleged to have commented on the costly year 1916, that ‘infantry [units] were fighting too close to each other and [were] too inelastic, the infantry used to stick to the ground, hence the whole system of defence must be structured in depth, broken up into flexible elements and consequently adjusted to the terrain.’

But the obsolete doctrine began to be watered down: Nau links the failure of the British 7th Division to secure Ginchy on that day to the fact that the Brandenburger FR 35 had left the village silhouette unoccupied - except for some doomed forward posts and observers. This unconventional - and unfortunately unarranged - step, together with the assignment of strong reserves hanging back in the rear trenches, at first had caused incomprehension within the ranks of IR 76 at Guillemont. It had been almost impossible to sustain liaison between both regiments, which in the end led to a risky gap in the front line between the two villages. However, in retrospect Nau pays expressive tribute to the far-sighted tactic of FR 35, actually the kind of flexible defence made obligatory later in the war. After the British had overrun the string of foxholes held by FR 35 around Ginchy they advanced into nothing, as the main body of Fusiliere was held in readiness to attack the British behind the village. Eventually the Germans counter-attacked with such vigour that the exhausted attackers had to withdraw by the end of the day. Ginchy didn’t fall until 9 September, when it was finally taken by the 16th (Irish) Division. Nau wonders whether the similar use of a more flexible tactic might have changed the outcome of the fight for Guillemont, too, but in the end remained doubtful with regard to the overall circumstances.

Anyway, one might be allowed to speculate that the relatively successful German 1917/18 model of a staggered outline of forces and an immediate, massive counter-attack from depth - Verteidigung aus der Tiefe (defence out of the depth) and enforced by the Hindenburg/ Ludendorff partnership in late 1916, would have made the taking of Guillemont far more difficult - and far more costly.

In retrospect, and with regard to the obvious imbalance of power and the unearthly fighting conditions, Nau speaks with utter admiration of the almost perfectly executed British attack and poses the question, whether the Germans at Guillemont were lacking not only force and organisation but willpower, too. With hindsight, Nau could find no hint for fatalism among the defenders, on the contrary, many examples of individual endurance could be documented during and after the battle. In the end his criticism was - besides a bitter remark on the complete failure of the German artillery on that day - directed towards the old- fashioned, ‘man-hungry’, inflexible defensive tactics of 1916 that had led the German Army to shed the blood of countless soldiers in the Somme battle, a loss she was never able to make good throughout the remainder of the war.

Statistics

The following figures provide some impression of the dimensions of the defeat the Germans suffered at Guillemont:

As mentioned previously, the three platoons of 5/76 had gone into battle with about 180 men in the front line on 31 August and left the field on 7 September with just six men unscathed. Casualties of this company alone have been listed by Nau as follows:

Killed: 30, missing (presumed dead): 22, died of wounds in hospital: 5, wounded and brought back: 55, wounded and captured: 49, in total: 161 officers, NCOs and men, about 90 per cent of its fighting strength.

8/76 had similar casualties, while the fatal losses of 6 and 7/76 had been lower, ironically due to the fact that they had been overrun more quickly by the British assault.

Major Nau’s battalion, 11/76, had gone into battle with about 700 rifles and he calculates that his total casualties during the deployment at Guillemont were some 450 men killed and wounded and about 150 to 200 men captured; again about 90 per cent of the battalion’s combat strength.

Nau rightly concludes that his battalion had actually ceased to exist on this significant day.

In his work Nau claims to have read an article from an English newspaper describing his own fate during the Battle of Guillemont on the afternoon of 3 September 1916: ‘We were witness to a moving scene. A senior German officer lay heavily wounded on a stretcher; the prisoners, before leaving, approached and shook hands. Several were weeping ...'

Acknowledgement

Sebastian Laudan is indebted to the editor for his assistance in preparing this contribution for publication.

Sources

Wilhelm Nau, Beitrage zur Geschichte des Regiments Hamburg, Vol. V Guillemot, (Hamburg: 1926).

H Voigt, Geschichte des Füsilier-Regiments

Generalfeldmarschall Prinz Albrecht von Preufien (Hannoversches) Nr. 73, (Berlin: 1938).

V Inglefield, The History of the Twentieth (Light) Division, (London: 1921).

Hussey/Inman, The Fifth Division in the Great War, (London: 1921).

Offiziersverein (Editor), Das Füsilier-Regiment Prinz Heinrich von Preußen (Brandenburgisches) Nr. 35 im Weltkriege, (Berlin: 1929).

Offizierverein (Editor), Geschichte des 4. Hannoverschen Infanterie-Regiments Nr. 164, (Hameln:1932).

Ernst Jünger, In Stahlgewittern (Storm of Steel), (Berlin: 1922/London: 2003)

References

(1) Dialogue between Leutnant Konig, 9/76, and one of his pickets before Guillemont, late August 1916.

(2) Intelligence Section of the General Staff, AEF, Histories of Two Hundred and Fifty- One Divisions o f the German Army which Participated in the War (1914-1918),: (Washington: 1920).

(3) Ernst Jünger in his epic work In Stahlgewittern (Storm of Steel) has given a detailed account on the situation before Guillemont. Jünger had been wounded in billets at Combles a few days before the main attack of 3 September 1916 and had to leave the battlefield, thus most probably was saved from suffering the fate of most of his men - death or captivity. His depiction nevertheless provides us with a gruesome firsthand image of this battle’s prelude.

(4) As the boundary between the 5th and 20th (Light) Divisions ran straight through 3/73, it is impossible to define the actual number of Germans within the attack zone of the latter.