Iris Hotblack and Alan ‘Balmy’ Morton : love letters from the Front

- Home

- World War I Articles

- Iris Hotblack and Alan ‘Balmy’ Morton : love letters from the Front

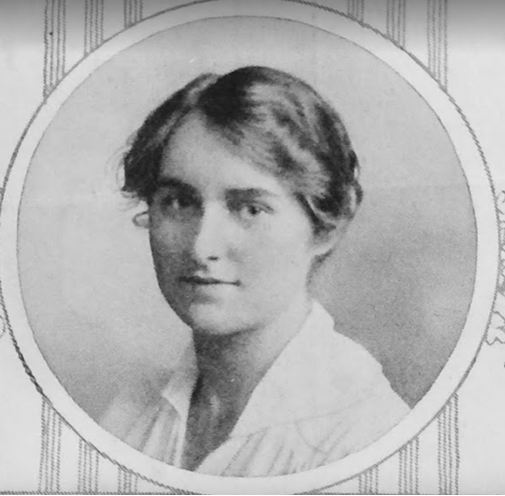

At the outbreak of war in 1914, 20-year-old Miss Iris Mary Hotblack was at home with her family. They lived in a large, Edwardian, detached, seven-room house called The Boltons on King Henry’s Road, Lewes, in Sussex.

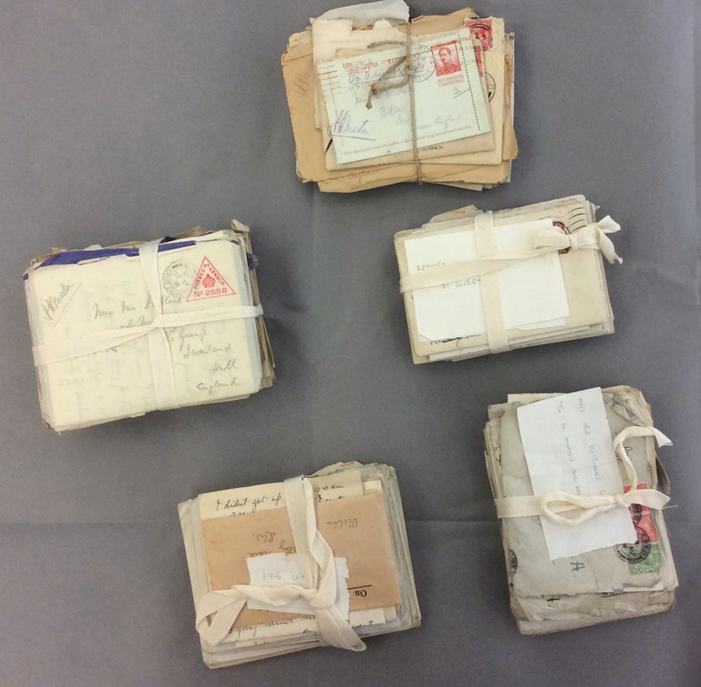

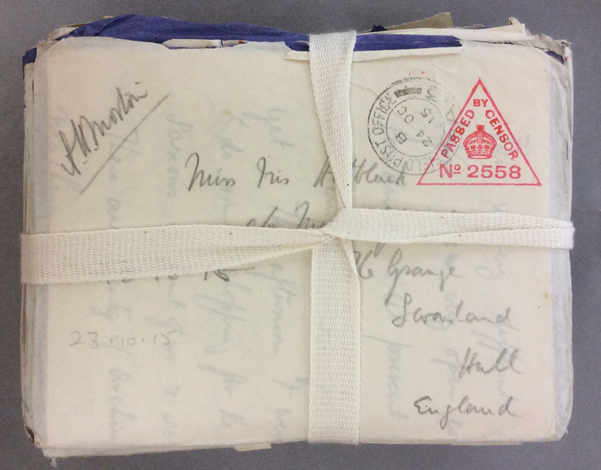

Iris had been sent away to school in Cheltenham, so she was used to living away from home and writing letters to stay in touch. She wrote regularly to her brothers and various other friends (male and female). Several bundles of these letters, some redacted, were passed to the Liddle Archive by Iris's daughter-in-law for safekeeping in 1985. Catriona Pennel came across them during her research for 'A Kingdom United'. For my MA research on an event in Lewes early on during the First World War, I also read through them.

Iris met Alan Morton when the families were on holiday on the Norfolk Broads in 1908. Nicknamed 'Balmy', Alan was then 18 and had just left Rugby to join the Royal Artillery. (The nickname 'Balmy' stuck when a sweaty young Alan joined a class late and his English teacher spoke to the class about the boy's 'balmy' complexion). Alan only dropped the monicker after he got engaged to Iris in 1915, signing off from then on as 'Alan' rather than 'Balmy').

During the war, Iris wrote weekly letters to Alan, her brothers, and other male and female friends.

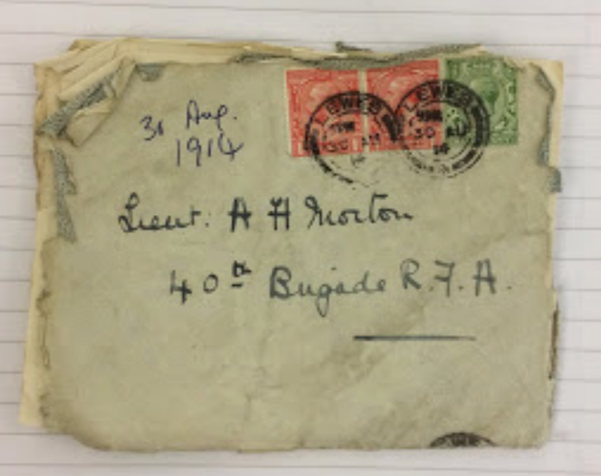

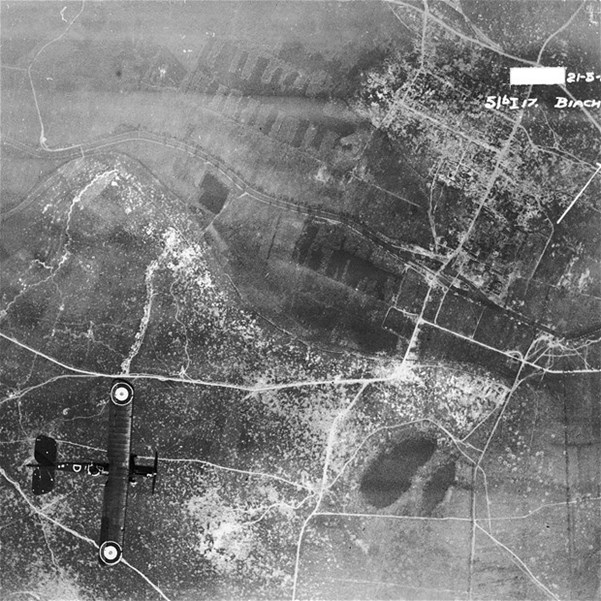

With the outbreak of war in August 1914, Alan was sent to France on 7th August 1914. He wrote to Iris about his experiences as a junior officer with the Artillery and later as a 'spotter' with the Royal Flying Corps, to whom he had successfully applied and where he was placed on secondment. Like so many back home, Iris was eager for detailed news that until 1915, the newspapers struggled to provide adequate accuracy due to censorship and a ban on correspondents on the front. As a result, the papers fell back on rumours, exaggerated hearsay and letters home that came to their attention.

Alan’s letters were typically two pages on paper pulled from a notebook, initially in ink but later in pencil. Writing his memoir in the early 1970s, Alan could detail the dangers of being caught up in Mons and the retreat to Paris, aerial reconnaissance trips in these early months of the war and the many close shaves he had while others were shot out of the sky or bombed back on land.

Iris also wrote regularly to close Lewes ‘pal’ Cecil Fawssett and her brother Gerald Hotbalck. Both had enlisted early, joining the 6th (Cyclists) Battalion, Sussex Regiment.

Cyclists of the 2/6th (Cyclists) Battalion, Royal Sussex Regiment

Whilst Alan’s letters might be described at this time as long notes that are sometimes quite perfunctory, Cecil, on the other hand, wrote chapters at a time, his letters often 14 pages long, gushing and expansive, waxing lyrical on every theme that took his fancy, as well as gossip about friends and family.

In several letters in August 1914, Iris wrote eagerly to Alan about the rumour of Russian soldiers landing in England and being sent to help the British soldiers on the Western front; she pressed Alan for any sighting of these men. In turn, Alan wrote that the famous pre-war aeronaut Gustav Hamel, he had heard, was a spy. In other letters, Cecil Fawssett joked about the rumour that Lewes barber, German-born 'Dusard' had been thought to be a German spy and that Iris’s father, who ran a manufacturing business, should watch out. Iris and Alan, though perhaps not Cecil, were caught up by widespread, unfounded rumours and common fears.

A few weeks later, when Iris had been staying with a friend in Hove, as she did regularly, she met some wounded men in Brighton and heard detailed stories of German atrocities carried out during the invasion of Belgium; in this instance, she told Alan that there had to have been some truth in what they had read in the papers. The realities and scale of this ‘great war’, this European War that Carrington described in The Times as the ‘first’ ‘world’ war, were gradually being understood. Lewes took in Belgian refugees, losses began appearing regularly in the local newspapers, and the hospital took in the injured.

At this time, Iris wrote sorrowfully to Alan to say that her cousin Nell, married only two months, had been left a widow by the war. With great pride, she also declared that she had recently persuaded two young men to enlist and didn’t know any men who had not done so. She often signed off her letters saying how proud she was to be the sister to and friend of many serving men.

Iris wrote to Alan about life in Lewes, including the so-called 'invasion' of some 10,000 recruits for Kitchener's New Army in mid-September 1914. Billets had to be found for them in a town that had a population of not much more than 10,000. At first, around half went into public buildings, including the Town Hall, Council Chambers and old Warehouse, while the other half were billeted on the public - whether they wanted men or not. The Hotblacks took in four men to start with, and then, with the sudden closure of the old Workhouse when deemed as unsanitary, a further two.

Prompted by advertising and promotions to volunteer in papers, posters, pamphlets, and public meetings, as well as the news of defeat in France as the British Army retreated, there was a massive rush to enlist in late August 1914 and early September 1914. Rather than turn these men away for weeks or months, plans were quickly put in place to share some 120,000 or more men between a dozen UK locations where they would be trained over 8 to 9 months. Men would go to Aldershot, Dublin and Wareham, Swindon and Salisbury, with two batches of around 10,000 men each destined for the South Downs, one group sent to the east of Shoreham near Patcham, the second headed for Seaford via Lewes.

In her letters to Alan, Iris remarked that 'her' men, all Welsh, would sing at the slightest invitation: national anthems and 'glee songs' were their favourites, with one a soloist of notable skill. At 'The Boltons', where the Hotblacks lived in Lewes, they had singing in the evening or took them around to a neighbour’s house for ‘'illuminated concerts' in the garden. 'Her' men, indeed all those billeted on the Workhouse, were sent to Eastbourne after a week due to 'sanitary reasons'; some went into private billets, others public. With a Regimental goat leading the way - a gift from Lewes people- the Cardiff Commercials marched off to Eastbourne on the morning of Monday 21st September 1914.

This friendly 'invasion' ended after two weeks, culminating in a Wales vs Lancashire football match on the Dripping Pan on Saturday, the 27th and a Church Parade on Sunday, 28th September, at the Convent Field, with many soldiers having to attend services in other places of worship around town. Iris was there with her friends. She described to Alan how proud and excited she was, so much so that she had wanted to join in.

Iris had been eager ‘to do something’ from the start of the war and frequently expressed her frustrations to Alan. Iris had at first taken on the organisation of women's hockey on the Convent Fields, though this, like all organised sports such as football and cricket, even rowing and tennis, were frowned upon in a time of war and thought of as frivolous - the last Association football game was played in November.

Iris recruited girls, ‘the best-looking 16 girls in Sussex,’ according to how she described them. She took membership fees, paid the costs to use the Convent Fields, and was the coach. Mary had lobbied those responsible for the Convent Fields and had even been interviewed by the Mayor. However, complaints frustrated her and being charged for using the grounds as if they were putting on a full game when only five or six of them had been down to practice irritated her further, and the hockey gradually ended.

Instead, Iris and a friend turned their attention to nursing as volunteers. They intended to spend three months cleaning floors and changing beds in London, only to learn that a 13 guinea fee was required for food and lodgings. Neither she nor her father was unwilling to pay this, nor did she feel committed enough to undergo the five years of training needed to become a nurse. In November 1914, Iris applied for and got a 'nanny governess' position with a family who lived near Hull. It was while here, on learning that his pal and Rugby study-mate Hugh, who lived close by to where Iris was now staying in North Lincolnshire, had met up with her, that Alan’s anxieties about ‘her close male friends still at home’ pushed Alan to act, if only by letter, he proposed, or rather suggested they might get engaged. Iris didn't turn Alan down but rather, in the kindest words, gave him ample hope and told him to wait. Iris also wished to explain and excuse the attention she received from Lewes boy Cecil Fawssett, her ‘closest male pal’ and the brother of her dearest female friend - one of his sisters. Cecil was in training in Norfolk at the time and would return to Lewes on leave - on one occasion teaching Iris how to ride his motorbike that, on several occasions, she took out on trips around the South Downs and later turning up in his 40hp Daimler.

Meanwhile, Alan and Iris continued to write and meet when he was on leave. In the summer of 1915, Alan completed RFC training at Gosport (having started as an artillery spotter and Observer, he went on to gain his pilot's certificate). Alan formally proposed while on leave in April 1916, and Iris accepted. They had an engagement party with Alan’s cousins in early May at The Savoy. They had intended to wait until the war's end to get married; however, when Alan was given three weeks' leave in June 1916, they agreed to get married.

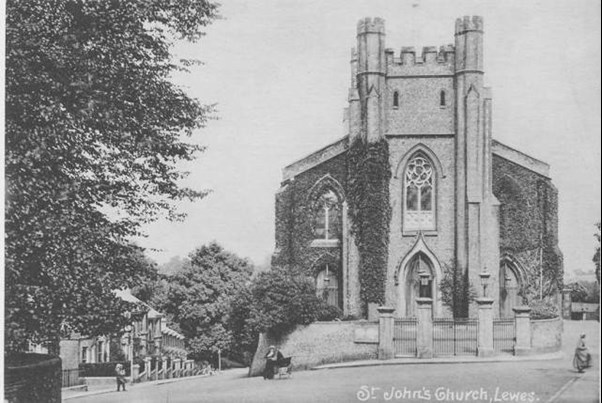

On the afternoon of Saturday, 3rd June 1916, a 'pretty war wedding took place at St.John’s Church, Lewes’.

Alan’s father and Iris’s brothers had each secured leave. Alan’s ex-military father, in his fifties and having been turned down when he had tried to enlist in 1914, had gone personally to Kitchener at the beginning of the war, had joined the Suffolk Regiment, and was now serving in France like his son.

Iris was ‘attired in white satin Charmeuse, draped with white Brussels net, with embroidered ornaments of crystals and diamanté. The full-court train was of white tulle. The bride also wore a veil, a chaplet of myrtle, and orange blossoms. Her only ornament was a string of pearls, the gift of the bridegroom, and she carried a posy of lilies of the valley’. In letters from Alan in July, he mentions finding a sprig of these lilies in his breast pocket. The bridesmaids were Miss Helen Culley and Miss Phyllis Kent. Captain Leslie Kent R.E. was the best man. The reception afterwards was held in the garden at the family home on King’s Road, Lewes. The wedding cake was ornamented with a miniature RFA gun and an aeroplane model.

The couple honeymooned in a house leant to them in Salcombe. Now a Captain, Alan returned to the Battle of the Somme and photographic reconnaissance duties with the Royal Flying Corps.

DH.4 over Biache-Saint-Vaast

Iris, meanwhile, the young wife, shared her time between her mother-in-law's, the Morton apartment in London, her family home in Lewes and a 'club' in London where she had more independence and could be with Alan when he was on leave.

Alan was awarded the Military Cross and ended the war a Major - his exploits written up in daily letters to his wife.

There are also letters from the war period to Iris from her brothers and from her friend Helen, who had married an American and spent her war in California and Hawaii, making remarks about how in America you could 'talk with the son of a miner or the son of a lord and not care who their grandfather had been' and that she hoped that ‘her snobbery had been knocked out of her’.

After the war, Alan remained with the Army; Iris gave birth to their first child in 1920. Her brothers Elliot, Gerald and Harold all survived the war; their youngest brother, Geoffrey, was killed in a bomb attack in Dublin in 1921 while serving with the Army.

Major Morton and his wife Iris were sent by the Army first to India for several years, then to Hong Kong and finally to Malta before returning to England for good in April 1939. They had two children.

Remembering and treasuring their honeymoon, Iris and Alan retired to Salcombe in the 1950s, and Iris died in 1969. Alan wrote his memoir in 1971, ending the story after Iris had a stroke and died a few days later. Alan moved to Eastbourne, where he died in June 1974.

Based on research conducted into the 'Friendly Invasion of Lewes 1914' when 10,000 recruits descended on the town for two weeks. This became his MA Dissertation while studying British History and the First World War at the University of Wolverhampton.

Written by Jonathan Vernon, Digital Editor, The Western Front Association, with grateful corrections by a great-niece of the couple written about here, Caroline Holland.

An intriguing postscript. Historic Photographic Studio Edward Reeves of Lewes, on the same site since 1855, took the wedding photographs for the marriage of Captain Alan Morton and Miss Iris Mary Hotblack. Tom Reeves showed me the original glass plates taken by his great-grandfather and digitised one or two for an exhibition in the town.