The Execution of the 'Iron Twelve'

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Execution of the 'Iron Twelve'

The early weeks of the First World War saw the Germans advancing across most of Belgium and large parts of northern France, although these mobile conditions were not to last as static trench warfare started to be the norm by the middle of September. During these first weeks of 'open warfare' the Allies were generally in full retreat and this led to considerable numbers of British and French soldiers becoming trapped behind the lines. The areas around Guise, St. Quentin, Le Cateau and Nouvion may have been thick with these soldiers, doubtless attracted by the presence of dense woods in which to hide. Those caught were at risk of being executed. The number captured and executed by the Germans is not known. Today the only evidence takes the form of the Commonwealth War Grave Commission headstones in quiet corners of communal cemeteries carrying a date of death long after the tide of battle had passed by.

Two encounters took place in the last days of August 1914 that resulted in a number of British soldiers being separated from the bulk of the army, which was retiring in a southerly direction in the face of the German onslaught. On 26 August the 2nd Battalion Connaught Rangers (part of the 2nd Division, under Major-General Sir Charles Monro) had been detailed to act as rear-guard to the retreat. Misinformed as to the Germans' position, battalion was encircled by them in an area around Marbaix and Grand-Fayt. They emerged with nearly 300 men missing.

Major-General Sir Charles Monro

The next day (27 August) the 2nd Royal Munster Fusiliers and two troops of the 15th Hussars were defending the crossings of the Sambre Canal between Catillon and Etreux, about six miles south-west of Le Grand Fayt. They came under German attack during the morning. Orders to retire from Brigadier-General Maxse, GOC 1 (Guards) Brigade never reached them.

Above: Brigadier-General Ivor Maxse.

Above: The 2nd Battalion, Royal Munster Fusiliers cheering the arrival of Lt.-General Lomax to present the Connaught Shield to the battalion's team prior to the war at Aldershot. Image courtesy of the Imperial War Museum. IWM Q113844

The RMF and 15th Hussars were left isolated as other units in the brigade on their flanks withdrew and by early evening their line of retreat across the canal (to the relative safety of Guise) had been severed. Surrounded by a much superior German force, the survivors surrendered that evening. The Battalion's war diary was unable to be written up, and instead was completed nearly four months later from a letter written by the senior surviving officer, Lieutenant Gower. His detailed account ends with the following passage:

"When getting into the orchard next to the road...I went to report to Major Charrier on the road. I found him by a deserted [machine] gun, the team of men were killed or wounded. Charrier was killed almost while I was talking to him. I had passed Simms dead."

Above: Major Paul Charrier commanded the 2nd Battalion Royal Munster Fusiliers at the Battle of Etreux and was killed in the action. Image courtesy of www.britishbattles.com

"I found that the enemy were attacking from the East, South and West. I told Hall this and shortly afterwards Hall and I led a small charge against one portion of the enemy and drove them back.... About 8pm those [soldiers] on the right of the road were driven to the left. Fresh enemy were coming up from the North so I surrendered at 9.12pm. Very little ammunition [was] left. I surrendered with 3 officers and 256 men. Other men tried to get away but 100 more were brought in next morning and after nine days there were 444 prisoners. We had exactly 100 wounded and 150 plus nine officers killed."

Above: The memorial marking the grave of the Royal Munster Fusiliers officers killed on 27th August 1914, erected soon after the battle. Image courtesy of www.britishbattles.com

Virtually all of the fatalities of this action are now buried at Etreux British Cemetery.

WFA member Hedley Malloch has estimated that about 120 men from the Munsters were "on the run" a week after the action. The number of men of the Connaught Rangers who were also at large after their action the previous day is impossible to estimate. Only three men from this action have known graves, being buried at Grand-Fayt Communal Cemetery.

The men from these two actions would not have been alone. It is without doubt that other stragglers found themselves behind the enemy lines. Many hid in the dense forests in the area.

The German reaction to these unwanted guests was initially tolerant. Any Allied soldier could come out of hiding and surrender and expect to be treated as a PoW. The Germans began issuing a series of proclamations giving Allied soldiers a period of grace (usually one or two weeks) in which to surrender.

Spending late August and September in the woods and fields, fed and guarded by villagers could have been an enjoyable experience – although cut off from friends, the men were not in imminent danger, and surely the war would be over soon? Yet as late summer gave way to the rain and mists of a cold autumn, many soldiers felt forced to seek somewhere warmer, drier and where food was more assured. This need appears to have been a compelling one, which forced at least nine British soldiers into the arms of villagers of Iron, a tiny place of just 500 inhabitants which is about three miles south of Etreux (and about 15 miles from Grand-Fayt).

Above: After the Battle. German Soldiers in Etreux. Image courtesy of Hedley Malloch's collection

On 15 October nine of men came into contact with the Logez family. The men, still in possession of their rifles, were scavenging for vegetables. They were taken in by Madame Logez who organised shelter in a large hut. The feeding of these nine, to be joined later by two others, was a big challenge, but with the assistance of other women of the village, food was ferried to the hiding place, which was now a mill to the north of the village.

These eleven soldiers were Privates Denis Buckley, Daniel Horgan, Fred Innocent, John Nash and L/Cpl James Moffatt of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Munster Fusiliers as well as Privates George Howard, Terence Murphy, William Thompson, John Walsh, Matthew Wilson of the 2nd Battalion Connaught Rangers, and finally L/Cpl John Stent of the 15th (The King's) Hussars.

A major alarm occurred on 15 December when German military police arrived at the mill on motorcycles. Madame Logez delayed them long enough for her daughter to warn the hiding soldiers to hurry away, out of the rear of the mill. In a small community such as Iron, it was impossible for secrets to be kept indefinitely. As a result of a feud between some of the villagers, on 22 February 1915, a resident called Monsieur Bachelet, a 66-year-old veteran of the Franco-Prussian War, informed the Germans of the presence of the eleven British soldiers. As a result of the incident just before Christmas, the men had by this time been moved into the village – to the house of Monsieur Vincent Chalandre.

Jeanne Logez, the 16-year-old daughter of Madame Logez described what happened:

"We realised that when we saw the road suddenly covered with Boches that the crisis had come. I tried as I had done on the first occasion to warn the soldiers... but it was impossible."

Above: A column of German troops circa 1914-15. Image courtesy Imperial War Museum IWM Q56791.

Despite being armed, the eleven put up no resistance when discovered. They probably realised to have done so would have made matters worse for the locals. Vincent Chalandre's house was burnt to the ground. The Germans also discovered the names of the Logez family who had worked to protect the eleven for so long. The family was rounded up and the mill was also burnt down.

However, of the French civilians implicated, it was Vincent Chalandre who was in the most danger. The eleven soldiers and Vincent were all transported to the nearby town of Guise where it is likely they went through a form of military tribunal, but this was almost certainly just for "show".

On the morning of 25 February the twelve men were taken to an area at the rear of the Chateau where they had been incarcerated for the previous 48 hours where s ditch had been dug. The significance of this would not have been lost on the prisoners.

With their hands tied behind their backs, the eleven soldiers and the Frenchman were shot.

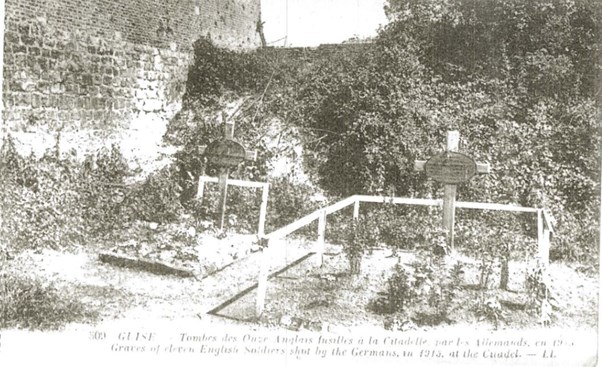

Above: An old postcard showing the original grave of the 12 at the execution site. Originally buried where they were shot, they were later re-buried in the Communal Cemetery at Guise. This photo was taken in 1919 or 1920.

Other French civilians implicated in the protection of the soldiers were given jail sentences.

After the war, the bodies of the twelve executed men were exhumed and reburied. The soldiers' bodies could not be individually identified and they were buried in a collective grave at Guise Communal Cemetery under the care of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

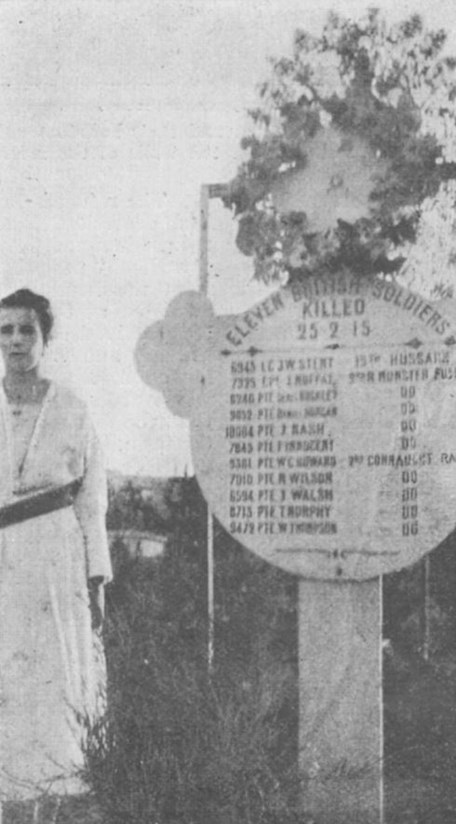

Above: Edith Hill, the sister of John Stent (one of the executed men) standing in front of a wooden marker on the collective grave in Guise Cemetery. Although undated, the photo is very early as the IWGC had not yet installed their headstones. As well as losing her brother, she was a war widow, losing her husband, Harold Hill of the London Regiment, in 1916. She had only been married for a few months.

Above: Robert Wilson, the younger brother of Matthew Wilson, another of the 12, taken sometime in the late 1920s. The Wilsons came from Galway. Note what appears to be the IWGC register box on the collective grave pressed into use as a hat stand by the photographer.

Vincent Chalandre was buried a few yards away. His grave was neglected and lost for many years, but in 2010 was restored as a result of the efforts of the Iron Memorial Fund.

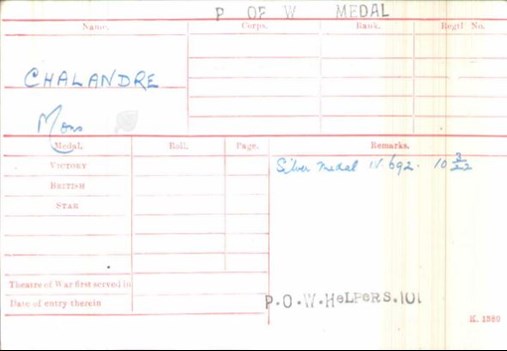

In recognition of the efforts, four members of the Chalandre and Logez families were awarded an "Allied Subjects Medal (Prisoners of War Helpers Medal)(Bronze)" in recognition of their efforts in sheltering the PoWs. Vincent Chalandre was posthumously awarded a Silver Medal.

The Medal Index Card of Vincent Chalandre. These cards were saved by the WFA when they were in danger of destruction in 2005.

In 2011 a monument was placed in the village of Iron commemorating the eleven men. There is also a simple marker at the Chateau in Guise marking the spot where they were executed.

Surviving Records

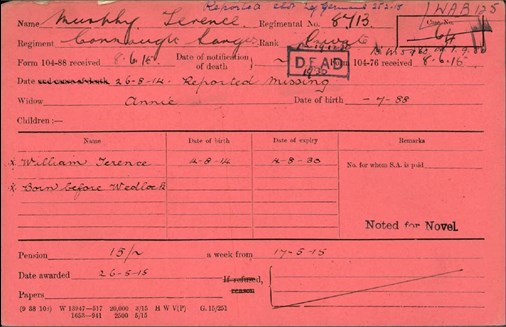

Unfortunately the only service records to survive of these eleven soldiers are those for Privates Denis Buckley and Matthew Wilson. Much more information was available using the WFA's Pension Ledgers as well as the WFA's Pension Cards. The card for Private Terence Murphy, for instance, states "Reported Shot By Germans 25.2.1915" and goes on to record that his widow was awarded 15 shillings per week.

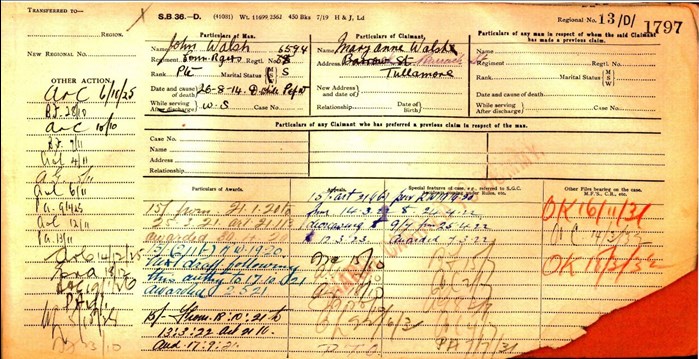

The ledger for John Walsh states that he "died whilst a Prisoner of War" giving the date of 26 August (being the date of his capture rather than date of execution).

Article by David Tattersfield

Acknowledgements

My thanks to Hedley Malloch for permission to use his research and photographs in this article.

Further Reading (web):

- Part one of the story of the Iron 12 (this is an article in the digital copy of Stand To!, to read this you will need to be a member of the WFA)

Further Reading (book):

- The Killing of the Iron 12 by Hedley Malloch. Available from Pen and Sword

Support the Iron 12 Memorial Fund

Although the memorial has been built, there are ongoing costs associated with its upkeep. If you wish to contribute to the ongoing maintenance of the memorial, donations can be made by cheque or credit transfer:

Name of Account: Iron Memorial Fund

Bank: HSBC, 12 Westgate, Guisborough TS14 6BE, United Kingdom

Sorting code & Account Number: 40-22-27; 01457055

Donations by Cheque: Cheques should be made payable to: ‘Iron Memorial Fund 40-22-27 account 01457055' and sent to the address of the bank detailed above.