The Battle of the Somme - A Royal Flying Corps perspective

- Home

- World War I Articles

- The Battle of the Somme - A Royal Flying Corps perspective

On 1st July 1916, the Battle of the Somme opened. With 60,000 casualties (including 20,000 dead) on the first day, this battle continues to fascinate and appal in equal measure. One aspect of the Battle of the Somme which is less well covered than others is that of the airmen who flew over the area during the summer and autumn of 1916, and later in the war. One pilot who wrote about the opening day of the Battle of the Somme in his memoirs is Cecil Lewis.

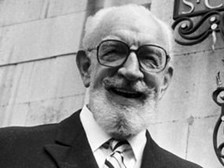

Above: Cecil Lewis.

"At La Boisselle the whole earth heaved and flashed, a tremendous and magnificent column rose up into the sky. There was an ear-splitting roar, drowning all the guns, flinging the machine sideways in the repercussing air. The earth column rose, higher and higher to almost 4,000 feet. There it hung, or seemed to hang, for a moment in the air, like the silhouette of some great cypress tree, then fell away in a widening cone of dust and debris."

Cecil Lewis - Sagittarius Rising (1936)

The results of the explosion that Lewis observed can be seen to this day.

Above: the mine crater at La Boisselle. Image courtesy of Friends of Lochnagar

Cecil Lewis was just eighteen years old (he had lied about his age to join the Royal Flying Corps) and was piloting a Morane Parasol monoplane (image: below) out of La Houssoye.

His observer/gunner in this two-seater was 'Pip' and was described by Lewis at some length in Sagittarius Rising:

Next day we were up at 3 a.m. and took the air at four. Dawn over the trenches, everything misty and still above, with the prospect of heat to come; even the war seemed to pause, taking a deep, cool morning breath before plunging into action. We were out to find the exact position at Boisselle, for even now, on the fourth day of the offensive, the Corps Intelligence did not seem clear on the point. We sailed over the mines and called for flares with our Klaxon. After a minute one solitary flare spurted up, crimson, from the lip of the crater. It looked forlorn, that solitary little beacon, in the immense pitted miles of earth around. We came down to five hundred feet and sailed over it, trying to distinguish the crouching khaki figures huddled in their improvised trenches in the khaki-coloured earth. It was not easy. We crossed the crater going north, wheeled south again to come back over it, when suddenly there was a crash, and the whole machine shook, as if at the next moment it would wrench itself into pieces.

I thought I had been hit by a passing shell. In a flash I pulled back the throttle and switched off. The vibration lessened; but we still shook fearfully. Now! Where to land? Five hundred feet over the front line, the earth an expanse of contiguous shell-holes! We should certainly crash, perhaps catch fire, right on the line! Such thoughts raced through my head as I looked frantically for some spot less battered than the rest. There was a place! Right underneath me! I dived at it, and the speed of the machine rose to a hundred miles an hour. Of course we could never hope to stay in that one green patch. We should overshoot, crash in the trenches beyond; but at five hundred feet there is no time to change your mind. You select your spot for better or worse and stick to it. So we dived.

“What’s the matter?” shouted Pip from behind me.

“Cylinder blown off, I think,” I shouted. (Actually it was a connecting-rod which had crystalised and snapped in half).

“Undo your belt!” I yelled. I didn’t want him to be pinioned under the machine when it caught fire, if it did catch fire.

By now we were down to a hundred feet, and the contours of the earth below took on detailed shape. I saw - God be praised! - that the green patch that had caught my eye was the side of a steep hill. There was no wind. I swung the machine sideways and pulled her round to head up the slope. She zoomed grandly up the hillside. The speed lessened. Now we were just over the ground, swooping uphill, like a seagull on a steep Devon plough. Back and back I pulled the stick. The hill rose up before me, and at last she stalled, perched like a bird on the only patch of the hill free of shell-craters, hopped three yards, and stopped - intact!

With a gasp of amazement and relief – for no one could have hoped to have got down in such a place undamaged - we jumped out of the machine. It was Pip’s twenty-first birthday. Suddenly I remembered it. “Many happy returns!” I said.

Cecil Lewis - Sagittarius Rising

In late September 1916 Lewis was sent home for a fortnight on sick leave. Upon returning, he found five men missing from the mess.

"Where's Rudd?" I asked. Only four chaps here. Where were the others?

"Killed. Archie [anti-aircraft fire]. This morning...."

...I couldn't believe it somehow.

"Suppose so. Machine took fire. Couldn't recover the bodies."

The boy who spoke was only eighteen too. A good pilot. Brave. Rudd had been his room-mate. God, how quiet the Mess was!

"And Hoppy?"

"Wounded: gone home."

"And Pip and Kidd?" I was almost frightened to ask.

"Done in last night. Direct hit. One of our own shells. Battery rang up to apologise. New pilots coming."

Lewis described Pip as

...the darling of the Flight, for he had a sort of gentle, smiling warmth about him that we loved. Besides, from the old rattling piano, out of tune, with a note gone here and there, he would coax sweet music - songs of the day, scraps of old tunes, Chopin studies, the Liebestraum, Marche Militaire.

He also went on to talk about Pip's talent on the mess piano

...enough for us, to make us sit quietly in the evening, there in that dingy room where the oil lamp hung on a string thick with flies, and listen.

Cecil Lewis - Sagittarius Rising

Pip, with whom Lewis had shared much of his time in the air during the early part of the Battle of the Somme is almost certainly Lt FES Phillips, MC who was killed along with his pilot, Lt LC Kidd, MC. They were flying a Contact Patrol and were shot down just before 2pm on 12 October 1916. Both are commemorated on the Arras Flying Services Memorial.

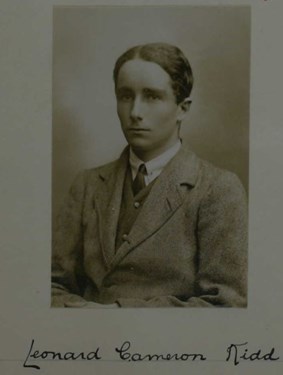

This is probably 'Pip', Lt FES Phillips. Image courtesy of www.dnw.co.uk

Above: Lt LC Kidd, who was killed with 'Pip' Phillips. Image courtesy of Ancestry.com. Great Britain, Royal Aero Club Aviators’ Certificates, 1910-1950 [database on-line]. (Royal Aero Club index cards and photographs are in the care of the Royal Air Force Museum, Hendon, London.)

Above: Arras Flying Services Memorial (image courtesy of the CWGC)

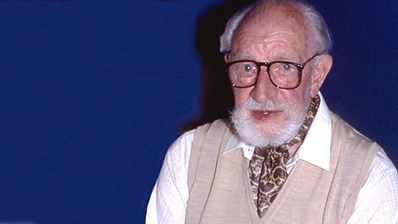

Against all the odds (pilots in the RFC had a very short life expectancy) Lewis survived the war. He lived to the ripe old age of 99.

Above: Cecil Lewis in 1991, aged 93 when he was interviewed by Sue Law Lawley for 'Desert Island Discs'

Of course, Lewis was not the only pilot in the air on the 1 July 1916. Among the many thousands of fatalities on this day was Captain Gilbert Webb.

Capt Webb, from 22 Squadron RFC, took off in his FE2b with his observer Lt Tudor-Hart at 10am. The short flight from Bertangles to the area of the 'offensive patrol' (between Douchy and Miraumont) would have taken only a few minutes. Whilst on patrol, they were attacked by several German aircraft. During the course of this combat, Webb was killed, and the aircraft crashed. Tudor-Hart was wounded and captured. Webb is buried close to where he fell, at Achiet-le-Grand Communal Cemetery Extension.

Earlier in the morning, 22 Squadron had lost another crew. Again flying a FE2b, Lt Firstbrook and Lt Burgess were shot down.

Above: An FE2B sortie. Image courtesy of Military Times / Mark Bromley (www.military-history.org)

Details of the combat appear in Pi in the Sky, by William Harvey:

I (Firstbrook) left the aerodrome ... carrying two 20 lb Hales bombs. When I reached the height or 8,000 feet, I crossed the German lines in the sector between Albert and the Somme. I remember releasing one of the bombs, but do not remember the target. From that moment on I remember nothing until I regained consciousness in a German Field Hospital on July 7th. I was wounded by a machine gun bullet entering my back between the spine and shoulder blade, and it travelled in a downward direction and lodging in the diaphragm. I was unconscious for six days from concussion caused by my machine crashing.

A newspaper report of the time describes his treatment:

His wound was very painful, and to his amazement and apprehension he discovered that he was to have an operation without general anaesthetic. No ether cup was to waft him into insensibility, no chloroform on a handkerchief to dull his brain to the surgeon's knife. In due course he was dumped upon an operating table and a hypodermic needle jabbed repeatedly into the region of his wound. Local numbness resulted and the German surgeons started in to mend four broken ribs in the gaping hole in his side.

Toronto Evening Telegram, Saturday 6 October 1917.

It seems Firstbrook was transferred to neutral Switzerland in December 1916 and arrived in London in September 1917. Although obviously badly wounded, he was luckier than Lt Burgess, who died of his wounds a week after being shot down. Burgess is now buried at Douchy-les-Ayette British Cemetery.

Commanding officers of squadrons were instructed not to fly, but this order was often ignored. Major 'Ferdy' Waldron commanded 60 Squadron, flying from Vert-Galant and took off with a patrol on 3 July.

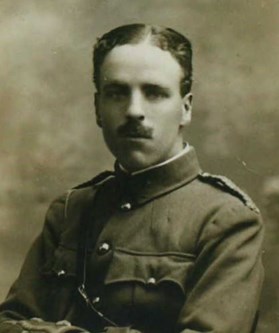

Above: Major Francis Fitzgerald ' Ferdy' Waldron as a Lieutenant in the 19th Royal Hussars. He gained his Royal Aero Club certificate (numbered 260) in 1912. Image courtesy of Ancestry.com

Both Armstrong and Simpson fell out, through engine trouble, before we reached Arras.... Waldron led the remaining two along the Arras-Cambrai road. We crossed at about 8,000 feet, and just before reaching Cambrai we were about 9,000, when I suddenly saw a large formation of machines about our height coming from the sun towards us. There must have been at least twelve. They were two-seaters led by one Fokker (monoplane) and followed by two others. I am sure they were not contemplating 'war' at all, but Ferdy pointed us towards them and led us straight in.

My next impressions were rather mixed. I seemed to be surrounded by Huns in two-seaters. I remember diving on one, pulling out of the dive, and then swerving as another came for me. I can recollect also looking down and seeing a Morane about 800 feet below me going down in a slow spiral, with a Fokker hovering above it following every turn. I dived on the Fokker, who swallowed the bait and came after me, but unsuccessfully, as I had taken care to pull out of my dive while still above him. The Morane I watched gliding down under control, doing perfect turns, to about 2,000 feet, when I lost sight of it. I thought he must have been hit in the engine. After an indecisive combat with the Fokker I turned home, the two-seaters having disappeared....I landed at Vert Galant and reported that Ferdy had 'gone down under control.' We all thought he was a prisoner, but heard soon afterwards that he had landed safely but died of wounds that night, having been hit during the scrap.

AJL Scott The History of 60 Squadron RAF

Waldron is buried at HAC Cemetery, Ecoust-St-Mein

As the Battle of the Somme ground on, RFC losses continued. Major Lanoe Hawker was one of the leading 'aces' by 1915 and a great tactical innovator. Because of this and his aggression, he was awarded the VC and also given command of 24 Squadron flying the single seat 'scout' DH-2. He took his new squadron to France in February 1916, but opportunities to add to his tally were limited due to the ban on commanding officers flying. Nevertheless, like Waldron, Hawker ignored the order.

Above: A DH-2. This type had sensitive controls and at a time when service training for pilots in the RFC was very poor it initially had a high accident rate, gaining the nickname "The Spinning Incinerator".

On 23 November 1916, Hawker left Bertangles Aerodrome at 1pm as part of 'A' Flight, Whilst over the Somme battlefield, Hawker lost contact with the other DH-2's, and became involved in a dog-fight with an Albatros D.II flown by Leutnant Manfred von Richthofen - the famous 'Red Baron'. Although the Albatros was faster and more powerful than the DH-2, Richthofen could not make his superiority pay off and fired 900 rounds during the fight, to no visible effect. Running low on fuel, Hawker eventually broke away from the combat and attempted to return to Allied lines.

Above: A depiction of the Hawker / Richthofen combat (left) and Lanoe Hawker VC (right). Both images courtesy of The 24 Sqn RAF Association "B Log Book" (https://the24sec.wordpress.com/2010/06/)

"I attacked, together with two other planes, a Vickers one-seater at 3,000 meters altitude. After a long curving fight of three to five minutes, I had forced down my adversary to 500 meters. He now tried to escape, flying to the front. I pursued and brought him down after 900 shots."

Manfred von Richthofen's combat report

The Red Baron's guns jammed 50 yards from the lines, but a bullet from his last burst struck Hawker in the back of his head, killing him instantly. His DH-2 spun from 1,000 feet and crashed 200 yards east of Luisenhof Farm, south east of Ligny-Thilloy. Although German infantry buried Hawker where he was shot down, after the war the grave could not be located. As a result, Major Lanoe George Hawker, VC is named on the Arras Flying Services Memorial.

The Somme in 1918

South of the River Somme is a remote, rarely visited private memorial (image: below) to two airmen, Captain Mond and Lt Martyn. Now weathered, the inscription is difficult to read.

Ce monument est érigé à la mémoire du

CAPITAINE FRANCIS L. MOND. RFC et RAF et du

LIEUTENANT EDGAR M MARTYN RAF

du corps d’aviation anglais, 57ème escadrille,

tombés glorieusement à cet endroit

en combattant contre les avions allemands

le 15 mai 1918.

Per ardua ad astra.

The story of the two officers is poignant. In May, 1918 Mond and Martyn were shot down and killed whilst on a bombing mission to Bapaume. Their DH4 bomber came down in no man's land just south of the River Somme. An Australian infantry officer went out, under fire, and extricated the bodies of the two airmen and brought them back to British lines. There they were identified as Captain Francis Mond and Lt Edgar Martyn, a Canadian. The bodies were sent away for a burial, but somehow they disappeared without the army keeping a record of the burial.

Despite an investigation by the army no trace of Mond and Martyn was forthcoming. It is possible that in the confusion of war-time this was not an unusual occurrence. However, the mother of Captain Mond refused to let the matter rest. She instigated further investigations, and, in 1920, presented a dossier of her findings to the Imperial War Graves Commission.

Acting on the information supplied, the graves of Mond and Martyn were identified at Doullens Communal Cemetery Extension no.2.

An American Airman on the Somme

July 1918 saw further fatalities to the RAF (as it had become when the RFC merged with the RNAS).

Ervin D Shaw, from Sumter, South Carolina, USA enlisted in the US Army in September 1917 and was first sent to Ohio State University, where he studied aviation, before joining the American Expeditionary Force in Britain, where he received further training at Oxford University. Shaw was subsequently sent to France for active duty, and attached to 48 Squadron which was flying Bristol Fighters (image: below).

During his time with 48 Squadron, Shaw was credited with shooting down two German aeroplanes, but just five days after celebrating American Independence Day, Shaw took off (from Bertangles) with his gunner/observer Serjeant Tom Smith at 6pm on 9 July on a reconnaissance mission. Attacked by three German Pfalz scouts, near the town of Albert, Shaw and Smith were shot down.

Tom Smith and Ervin Shaw were killed in this action, and are now buried side by side at Regina Trench Cemetery. (The link takes you to short video of Regina Trench Cemetery, shot by Stephen Kerr using a drone). Shaw is one of the very few Americans to be buried in a CWGC cemetery.

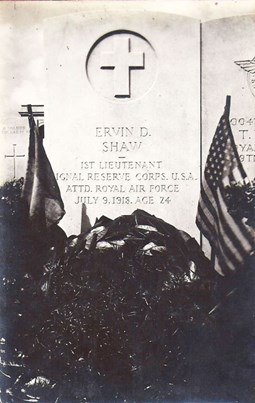

Above left: Lt Ervin Shaw. Image courtesy of www.scnow.com

Above right: The headstone of Ervin Shaw, Regina Trench Cemetery - next to this headstone is that of his gunner, Tom Smith. Image courtesy of www.theitem.com

To honour Lt Shaw, the US government named the basic flying school at Sumter (South Carolina), 'Shaw Field'. The Shaw Air Force base in Sumter Counter is still operational and is now one of the largest military bases operated by the United States.

Further Reading:

Cecil Lewis: Sagittarius Rising

Peter Hart: Somme Success: The Royal Flying Corps and the Battle of the Somme 1916

WFA Articles

If you are interested in other articles about the RFC or RAF during the First World War, the WFA web site has the following pieces:

Rex Warneford and the downing of LZ37

Biggles’ Last Flight: the flying career of Captain WE Johns

Other Media

A full interview with Cecil Lewis has been preserved. The interview was conducted in 1963 by the BBC and is now one of the many hundreds of interviews held by the Imperial War Museum. These interviews were originally on reel-to-reel tapes, but in danger of disintegrating until The Western Front Association made a substantial donation to enable these recordings to be digitised by the IWM some years ago. The two recordings below (each in excess of 20 minutes) are truly fascinating and well worth listening to.

Above - Cecil Lewis

The full version of a podcast of the 1991 BBC interview of Cecil Lewis by Sue Lawley can be downloaded via this link to 'Desert Island Discs'

Youtube

In 'A Recreation of Wings' we can see a presentation by Mike O'Neil. of the Golden Age Air Museum of Bethel, Pennsylvania. Mike's talk gives the fascinating inside stories behind the Museum's creation of several flying replica World War I aircraft including a Fokker Dr I triplane, Sopwith Pup, and a SPAD XIII.

Article by David Tattersfield