‘Unfading Memories’: The Hot Lane and Elder Road Street Shrine

- Home

- World War I Articles

- ‘Unfading Memories’: The Hot Lane and Elder Road Street Shrine

When the British government chose to go to war in August 1914 it had no understanding of what would follow. This is reflected in the comments of Sir Edward Grey, the Foreign Secretary, when he said in his speech to the House of Commons on 3 August that ‘if we are engaged in war, we shall suffer but little more than we shall suffer even if we stand aside’. It was to be a ‘traditional’ British war. Britain’s contribution would be primarily naval. A naval blockade of Germany, in conjunction with Britain’s dominance of international finance, trade, shipping and communications, would constitute a ruthless economic war that would eventually bring Germany to the conference table or to ruin. Britain’s military contribution would be confined to the despatch of a small expeditionary force to France, where its presence was primarily political, a symbol of Anglo-French solidarity. No one expected the BEF to ‘win the war’.[1] This all changed after the appointment of Lord Kitchener, the Empire’s most famous living soldier, as Secretary of State for War on 6 August. Familiarity with this fact dulls our appreciation of just how astonishing Kitchener’s appointment was. Even more astonishing was the Cabinet’s unquestioning acquiescence in Kitchener’s announcement, on 7 August, that Britain must raise a mass army and keep it in the field for at least three years. This changed everything. Without a mass army Britain could not have experienced the mass casualties that have since dominated British perceptions of the war. And, quite probably, Germany would have won the war.

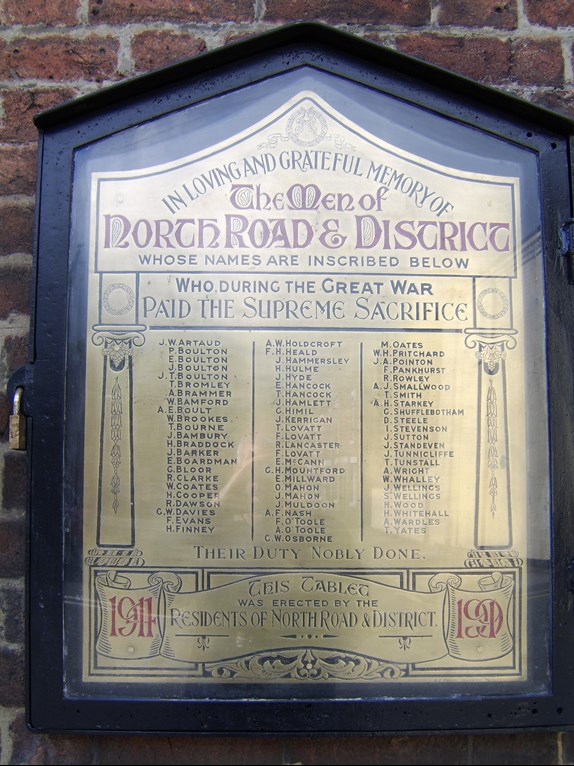

The unprecedented casualties suffered by Britain required a new vocabulary and ritual of remembrance – the war cemeteries on the Western Front and elsewhere, the memorials to the ‘missing’, the Cenotaph, the Minute’s Silence, Armistice Day, the wearing of poppies, official, national and civic memorials and small local memorials on pubs, streets and factories.[2] This article focuses on one such small, local memorial, which is officially classified by the War Memorials Archive as ‘The Hot Lane and Elder Road Street Shrine’.[3]

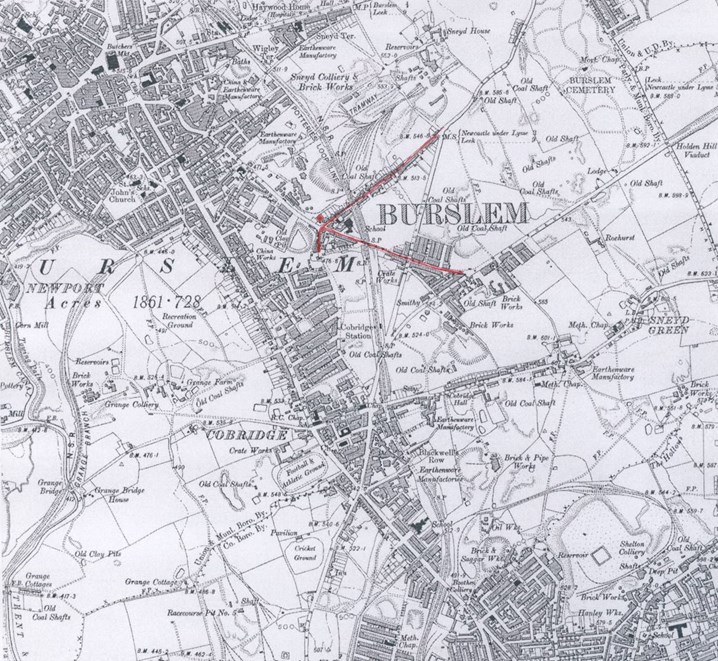

Above and Below: Burslem from a 1898 OS map. The streets shown below in red are Hot Lane and Elder Road, with the 'Dog and Partrridge' pub on the intersection of these streets also shown in red.

Location, Location, Location

The memorial is fixed to the wall of what was the ‘Dog & Partridge’ public house, 5 Hot Lane, Burslem, the ‘Mother Town’ of the Staffordshire Potteries, which ‘federated’ in October 1910 to form the Borough of Stoke-on-Trent.[4] The memorial’s location and the streets that it covered are shown in red on the map. When the pub was closed in 1960s the building was taken over by the Boy Scouts and used by them until 2003. After a period of disuse the building was sold and converted into flats.[5] Why it was fixed to this pub is a moot point. There were no shortages of pubs in the immediate vicinity. The Alma Inn was just across the road on the corner of North Road and Elder Road, the Ship Inn was further up Hot Lane and the White Swan, completely rebuilt in 1912, beckoned from the corner of Elder Road and Bleak Street. North Road also boasted the Lord Raglan and the Railway Hotel.

Above and below: The (former) pub the 'Dog and Partridge on Hot Lane. The memorial can be seen on the right of the building.

The memorial is made of stone. It consists of an ‘inscription tablet set within a frame formed by two columns supporting a triangular pediment’. It is 54 inches [1370mm] high, 35 inches [880mm] wide and 6 inches [160mm] deep. The top inscription reads ‘IN MEMORY AND HONOUR/ OF THE MEN FROM HOT LANE & ELDER RD/ WHO FELL IN THE GREAT WAR 1914 – 1919’. This is followed by the list of names, thirty-six in all. The bottom inscription reads ‘WHOSE SELF SACRIFICE HAS LEFT BEHIND IT/UNFADING MEMORIES/ SUBCRIBED [sic] FOR BY NEIGHBOURS& FRIENDS/ THIS TABLET WAS UNVIELED [sic] BY/ DR GOOD’.[6]

The list of names is separated by a short line. Twenty-three names appear above this line; eleven appear below it. Although the evidence is not conclusive, it appears that the names above the line were of men who came from Hot Lane and those below it of men who came from Elder Road.[7] Two names, those of T. Hancock and W. Turner, appear alongside the dividing line, apparently added after the memorial had been completed.

Above: The memorial on the former pub

It is apparent every November that the memorial still functions as a ‘site of memory and a site of mourning’.

The Memorials Context

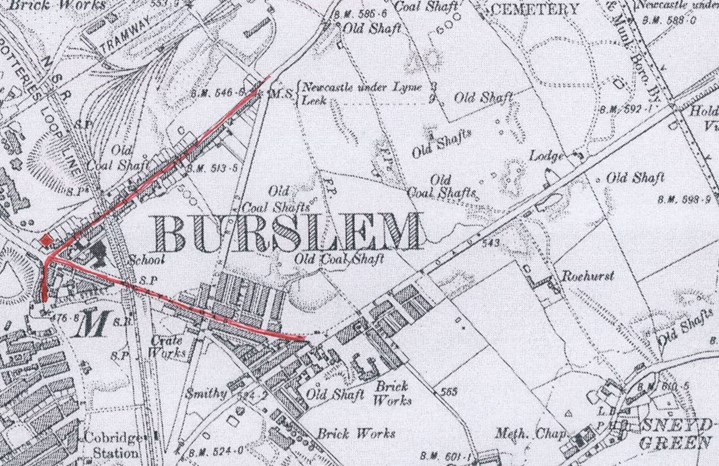

The Hot Lane memorial needs to be seen in the context of two other memorials close by: the North Road memorial; and the Christ Church memorial.[8] None of them has a date of unveiling. Nineteen of the thirty six names on the Hot Lane memorial also appear on the North Road memorial, which has a total of 70 names;[9]eight are on the Christ Church memorial, which has a total of 124 names.[10]

Above: The North Road Memorial

One name, that of Thomas Yates, appears on all three memorials. Twenty-one of the names on the North Road memorial also appear on the Christ Church memorial. Hot Lane, the northern end of Elder Road and most of North Road were not in the parish of Cobridge, but in the parish of Sneyd. The Sneyd parish church, Holy Trinity, was in Nile Street, next to the Doulton factory. It was demolished in 1959 because of mining subsidence. After the church was declared unsafe in 1956 the congregation and furnishings were transferred to St Werburgh’s in Hamil Road. This was re-consecrated as Holy Trinity, Sneyd, in 1958. It is not currently known whether thechurch had a war memorial. The North Road memorial migrated over the years. Its last resting place before being moved to Christ Church in July 2013was on the wall of a pub, Bennett’s Inn, at the top of North Road. Before that it was fixed to the wall of the Junction Inn (originally the Railway Hotel) at the corner of North Road and Sandbach Road. It is believed that the memorial was brought there by the licensee when he left another pub at the bottom of North Road. This may have been the Alma Inn, which was on the corner of North Road and Elder Road (and directly opposite the Dog & Partridge), or the Lord Raglan, a bit further up North Road, opposite the primary school.[11]

This account suggests, though does not prove, that the Christ Church memorial came first, but was felt by locals to be inadequate because it did not include the names of men who had lived nearby but outside the parish. It then looks suspiciously like the Hot Lane memorial was created to include the seven men who were on neither of the other memorials: Bamford, Harding, Hulson, the Lightfoot brothers, Turner and Vaughan. The inclusion of twenty-one names that appear on the North Road memorial strongly suggests that the Hot Lane memorial came last. If the North Road memorial came after the Hot Lane memorial it would surely have included all the Hot Lane names on it.

Above: The Chris Church Memorial

The Local Context

Burslem

At the time of its post-war unveiling, the memorial’s address could be officially and correctly rendered as 5 Hot Lane, Stoke-on-Trent, the borough created out of the ‘federation’ of the six Potteries towns in October 1910, but the concept of living in this new construct took time. It is significant that each of the Potteries towns produced its own war memorial and that no borough-wide war memorial was erected. Hot Lane was most definitely in Burslem, but it was on a frontier. Elder Road was most definitely in Burslem’s suburb, Cobridge, as was North Road.

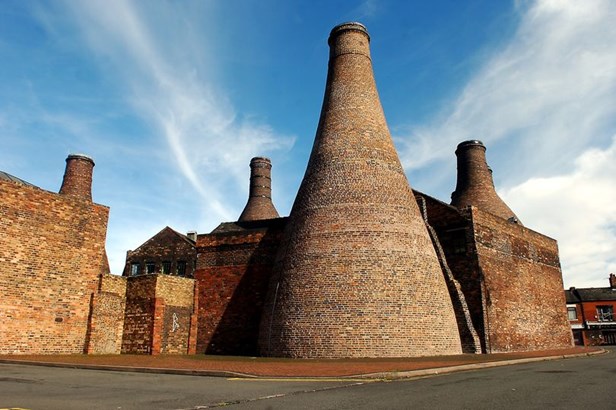

Burslem was the quintessential industrial town, dominated by potbanks and coal mines. It was a town of manual workers, most of whom would have joined the workforce aged twelve. ‘Zoning’ was an unknown concept in the Potteries. Accommodation existed side by side with factories and mines. It was a world experienced on foot. Most people lived within comfortable walking distance of their employment. This included Sneyd Colliery and brickworks, the Grange Colliery, Hanley Deep Pit, Sandbach Pit and the Racecourse Pit. Potbanks within easy reach included Boote’s, Doulton’s, Furnival’s, H. & R. Johnson, Macintyre’s, Myott’s, Sudlow’s and many more. Parker’s Brewery was off Nile Street, in Pitt Street East.

Above: A surviving example of one of the Potbanks. This is at Gladstone Pottery Museum, Longton, Stoke-on-Trent

This was reflected in the employment of the men on the memorial. Eighteen were miners, the majority of them employed at the Sneyd Colliery, seven were potters, two worked in brewing, one in brick making, one in metals, one in baking and one in transport (carter). There was one police officer and one ship’s stoker, both of whom had originated in the area, but no longer lived there.[12]

Hot Lane and Elder Road

Hot Lane and Elder Road, in my experience, were very different. Hot Lane was a densely populated street of older, two up and two down working class-houses, most of which had been demolished by the time I was old enough to notice. The 1911 Census recorded 118 households. These were occupied overwhelmingly by manual workers and their (often large) families.[13]Besides the Dog & Partridge, there was another pub, the Ship Inn.[14] The street also contained a chapel, belonging to the Methodist New Connexion, which was virtually opposite the Dog & Partridge.[15] Elder Road, in contrast, was much more sparsely populated. Most of the eastern side was occupied by a recreation ground and by Cobridge Park, opened in 1907.[16] The housing on the western side of the road, especially at the Cobridge end, was newer and better and was occupied less by manual workers and more by people in managerial and clerical occupations and by shopkeepers.[17]

This contrast is less apparent, however, when the housing at the northern end of Elder Road, closest to Hot Lane and to the Dog & Partridge, is considered and helps explain the location of the memorial. The 1911 Census recorded eight houses on the eastern side of Elder Road, extending from the junction with North Road to Flint Street (since renamed Ashburton Street). No. 1 Elder Road was also a pub, the Alma Inn. There were a further four houses behind this row in ‘Back Elder Road’. There were seven houses on the western side of the road running from the junction of Elder Road and Nile Street almost to Bleak Street (now known as Orgreave Street). This housing was very similar to that of Hot Lane and so were its inhabitants and it is here that the men whose names appear on the memorial lived.[18]

The Military Context

There were broadly two types of British soldiers who fought in the Great War: volunteers and conscripts. The voluntary system survived until the spring of 1916. Conscription was introduced for single men by the Military Service Act of January 1916. Conscription began on 2 March. The act was extended to married men on 25 May 1916. Conscription did not, however, end the possibility of volunteering. Men sometimes anticipated their ‘call up’ under the Military Service Acts in the belief that volunteering would give them more control over the branch of the army to which they were sent. The conventional wisdom is that slightly over 50 per cent of British soldiers were recruited after the introduction of conscription, but it is clear from the work of Alison Hine and from the histories of Burslem soldiers in the Great War, including some on the Hot Lane memorial, that it is inappropriate to equate soldiers who joined the army after 2 March 1916 with conscripts.

Conscripts are, in many ways, remarkably elusive. They were, in Ian Beckett’s felicitous phrase, the true ‘unknown army’ of the Great War.[19] There is no doubt that volunteers looked down upon the men who ‘had to be fetched’.[20] This has resulted in a lazy association of ‘conscript’ with ‘shirker’, but in truth most conscripts were simply men who had been too young to volunteer in 1914 and 1915 and it is inappropriate to deduce their attitude to the war from their military status.[21]

Twenty of the thirty six men whose names appear on the Hot Lane memorial were definitely volunteers (60.6 per cent) because they were awarded either the 1914 Star or 1914-15 Star. The number is probably an underestimate. It was possible to volunteer before the end of 1915 and not be sent abroad until after 1 January 1916, when it was no longer possible to qualify for either of the Stars. It was also possible to volunteer after 1 January 1916.

Staffordshire has some unusual military features. It was one of only five English counties, the others being Kent, Lancashire, Surrey and Yorkshire, that had more than one ‘county’ infantry regiment. The county, along with Nottinghamshire, was one of the most fertile recruiting grounds for the pre-war Regular army. It was also the county that showed the greatest level of support for the Territorial Force, formed by R.B. Haldane in 1908.[22]

The North Staffordshire Regiment on the eve of war consisted of two Regular battalions (1st and 2nd), two reserve battalions (3rd and 4th) and two Territorial battalions (5th and 6th).[23] The 1st Battalion was stationed at Buttevant, in Co. Cork. It was mobilized as part of the original BEF and spent the whole of the war on the Western Front. The 2nd Battalion was stationed in Rawalpindi. It remained in India for the duration of the war. The 5th Battalion was based in the Potteries, the 6th in Burton-on-Trent. Following Lord Kitchener’s call to arms on 7 August a further five battalions were raised, the 7th, 8th, 9th, 10th and 11th. The 7th was the first to be raised, formed at Lichfield on 29 August 1914, which makes it a ‘K1’ battalion, composed of men who were among the ‘first hundred thousand’ to volunteer. Its origins are obscure.[24] The 8th was formed at Lichfield on 18 September 1914 by Major Cecil Wedgwood, first Mayor of the Borough of Stoke-on-Trent, followed two days later by the 9th.[25] The 10th and 11th were Reserve battalions.

The period of voluntary recruitment is associated with the phenomenon of local men serving in local units. In North Staffordshire this meant the Territorials as well as the New Army.[26] 5th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment was part of 137 (Staffordshire) Brigade, 46th (North Midland) Division. In March 1915 46thDivision became the first Territorial division to be deployed to France as a complete formation.[27] Burslem’s Territorials were the first to feel the full fury of the Great War.[28] The attack by 46th Division on a German strongpoint, known to the British as the Hohenzollern Redoubt, on 13 October 1915 was a disaster. Even the normally restrained British official historian, Sir James Edmonds, concluded that the attack achieved nothing but ‘a useless slaughter of infantry’.[29] 13 October 1915 was the worst single day of the war for Burslem. Even the use of the 46th Division again in a pointless diversionary attack at Gommecourt on 1 July 1916 did not inflict the level of casualties sustained at the Hohenzollern Redoubt.[30]

Remarkably, however, none of the men on the Hot Lane memorial was killed on 13 October 1915 or on 1 July 1916. Only one of them, Philip Roberts, was aTerritorial. He volunteered for the third line battalion (3/5th North Staffords) in April 1915 and was not sent abroad until February 1917. He died of his wounds in October 1918 while serving with ‘D’ Coy, 1/6th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment.

The unit that figures most prominently on the Hot Lane memorial is the 7th (Service) Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment. It formed part of 39 Brigade, 13th (Western) Division. After training on Salisbury Plain and in and around Aldershot, the battalion sailed from Avonmouth in June 1915. It landed on the Gallipoli peninsula on 11 July 1915.[31] It transferred to Mesopotamia in February 1916. 13th Division was the only British infantry formation to serve in Mesopotamia. During April 1916 it took part in the third attempt to relieve Major-General C.V.F. Townshend’s force, which had been besieged at Kut-al-Amara since 7 December 1915. The first phase of this attempt went well. The Turkish positions at Hanna and Falahiya were taken on 5 April 1916, but three attempts to force the Turkish defences at Sannaiyat (6-22 April 1916) failed and Kut fell on 29 April.[32]

The prominence of service with the 7th North Staffords meant that a third of the men listed on the memorial did not serve on the Western Front. The men who volunteered for this battalion in August 1914 would surely have seen themselves as responding to an existential threat from Germany. Britain was not then at war with the Ottoman Empire. It is a moot point what they made of being shipped thousands of miles from home to fight Turks.[33]

It is often asserted that men joined their local units during the period of voluntary recruitment, but after the introduction of conscription the local link was broken and men were sent where the army needed them. The Hot Lane memorial supports neither of these assertions. Of the thirty-six men listed on the memorial, twenty did not serve with the local infantry regiment. Three (J. Boulton, Rowley and D. Lightfoot), were Reservists; nine (Artaud, E. Boulton, Cavenor, Ford, Lewis, O. Mahon, Standeven, Sutton and Vaughan) were volunteers. Artaud was a guardsman, Cavenor a gunner and Lewis a sapper, but Boulton, Ford, Mahon and Standeven joined non-local infantry regiments during the period of voluntary recruitment. There is a possible explanation for this. The local Territorial battalion, 5th North Staffords, was pretty well up to strength when the war broke out. It had little room for wartime volunteers. The 7th, 8th and 9th Service battalions quickly filled up. Men who left it a bit later than others may have found themselves with no space available in local units.

On 1 September 1914 57.56 per cent of the total strength of the army was infantry; by 1 October 1918 the proportion of infantry had declined to 32.83 per cent. There were 92,920 officers and men in the artillery on 1 August 1914; by 1 August 1918 there were 548,780. There were 1,295 officers and 10,394 men in the Royal Engineers on 1 August 1914; by 1 August 1918 there were 11,830 officers and 225,540 men. There had been an equally huge rise in the non-combat support arms. The proportion of the army that was non-combatant doubled from 17.64 per cent on 1 September 1914 to 34.21 per cent on 1 October 1918. The Labour Corps alone constituted 14.16 per cent of the army by October 1918.These changes are not reflected on the Hot Lane memorial. All but three were in the infantry. The exceptions were Frank Cavenor (Royal Field Artillery), Thomas Lewis (Royal Engineers) and Frank Lovatt (Machine Gun Corps). Lovatt was arguably an infantryman, too. There was no one in the Army Service Corps, a branch of the army that expanded from 5,933 other ranks on 1 August 1914 to 314,693 other ranks by 1 August 1918.

Analysis of the names on the memorial does not support the view that the response to the ‘call to arms’ was one of naïve patriotism by callow young men who thought it ‘would be over by Christmas’.[34]Their average age at deathwas 28.1 years. The youngest was Percy Boulton (18) and the oldest Thomas Yates (52).Nineteen were married, most of them with families. Many would have been in the workforce, often in physically demanding jobs, for ten to fifteen years by the time they volunteered. They had lived in the ‘real world’. The history of John Wellings is instructive. His was no ‘mindless’ rush to the colours. He did not enlist until 12 February 1915. By then he was 33 years old, had been married for fifteen years and had three children. It is also unlikely that he had a ‘naïve’ view of war because his older brother, Samuel, a Reservist, had been killed in action on 21 September 1914.

Putting Histories to Names

The memorial presents several problems, principally the number of surnames that are common in North Staffordshire, names such as Hancock, Hulme, Lovatt, Sutton, the absence of Christian names, ranks or units and misspellings.

The sources for researching British service personnel are numerous but problematic.[35] The ‘starter source’ in trying to identify the names on the Hot Lane memorial was the list Soldiers Died in the Great War [Soldiers Died]. This was published in 80 volumes in 1921 by His Majesty’s Stationery Office on behalf of the War Office.

Above: Soldiers Died in the Great War Part 16 - The Devonshire Regiment

It has been digitized as a searchable data base by the Naval & Military Press.[36] It is possible to search by soldier’s name, by his date of death, by his regiment and/or battalion and by his place of birth, place of enlistment and place of residence at the time of his joining the army.[37]Thirty-four of the thirty-six names on the memorial could be traced in Soldiers Died. The exceptions are J. Barker, who is unaccountably missing from Soldiers Died, but who has been identified from other sources, and D. Lightfoot, for whom see below (and elsewhere)!

A search was then made for soldiers’ service files, which have been available on line for some time. These files suffered massive damage during the first German night air raid on London on 7/8 September 1940, when the Arnside Street repository was hit by incendiaries. Thirteen of the men on the memorial have service or pension files that have survived at least in part. This is about the ‘national average’. These files, when available, are revealing and often moving.

Further checks of the names were then made of the Medal Roll Index Cards [MRIC], the Medal Rolls and the Registers of Soldiers’ Effects. The MRIC for 1914 and 1915 often show the date of entry of the soldier into a theatre of war and which theatre he entered. The Registers of Soldiers’ Effects provide valuable information on soldiers’ next of kin as well as their place of death. Pension Cards are extremely valuable for confirming family links.

The names derived from Soldiers Died were supplemented by wartime obituaries in the local newspaper, the Staffordshire Weekly Sentinel, whose coverage of losses never slackened with familiarity.

Above: Staffordshire Weekly Sentinel

Most of the reports, which often include photographs, were submitted by close family and often give background information as well as an insight into how the war was being perceived. The Sentinel reports also provide useful information about addresses. This memorial is an intensely local one. The men whose names are found on it, or their families, must have had at some point a close connection with Hot Lane or Elder Road, though this is often not evident from the censuses or, indeed, from other sources.[38]

The Names

ARTAUD, J. 17286 Lance Corporal John William Artaud, 2nd Battalion Grenadier Guards, who was killed in action on 15 September 1916,aged 22.

2nd Grenadier Guards were part of 1 (Guards) Brigade, Guards Division. At 6.20 am on 15 September 1916 the battalion attacked German positions at Ginchy on the Somme. This action was part of the Battle of Flers-Courcelette, which is now best remembered for the first use of tanks in war. The battalion managed to pass through a German barrage with remarkably few casualties, but later suffered heavily from machine gun and rifle fire coming from their right flank, where the British attack had failed.

John Artaud was apparently born in Smallthorne in 1894,[39] the son of Charles Woodfield Artaud (b. 1859), a bricklayer, and Ann(ie) Artaud (née Barrow, formerly Ford) (1853-1914), of 22 Unwin Street. His father was born in Southampton and his mother in Barnsley. In 1911 he was living with his parents and his sister, Emily, at 124 Leek New Road, Cobridge, and was employed as a driver at a coal mine. No evidence has been found of a closer connection with Hot Lane or Elder Road.

Lance Corporal Artaud has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial, Somme, France. His name also appears on the North Road Memorial, now in Christ Church, Cobridge. Kitchener Volunteer: 1914-15 Star; BWM; VM.[40]

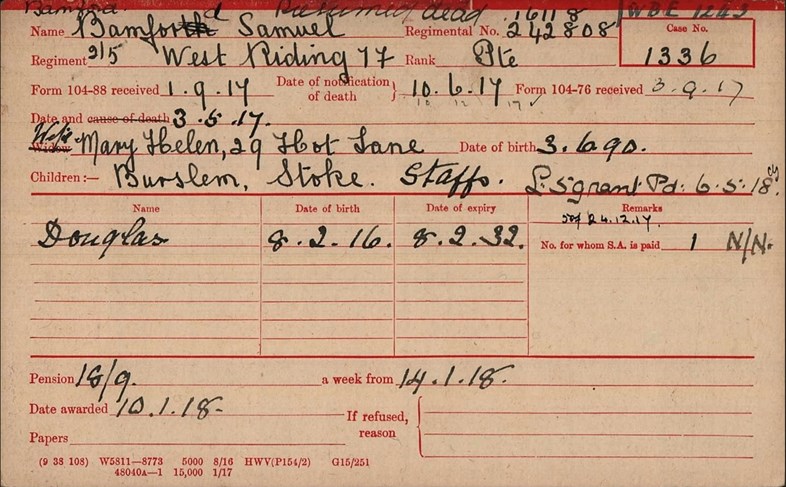

BAMFORD, S. 242808 Private Samuel Bamford, 2/5th Duke of Wellington’s Regiment, who was killed in action on 3 May 1917, aged c.31.[41]

2/5th Duke of Wellington’s Regiment was part of 168 (2nd/2nd West Riding) Brigade, 62nd (2nd West Riding) Division TF. The division had been on the Western Front since January 1917. On 3 May 1917 2/5th Dukes were involved in the Battle of Bullecourt, the notorious ‘Blood Tub’. Samuel’s was one of 168 fatalities that befell his battalion on 3 May as it advanced through Bullecourt village before being compelled to fall back..

Soldiers Died gives Bamford’s place of residence as Stoke-on-Trent and his place of enlistment as Burslem. His place of birth is stated as ‘Honley, Yorkshire’.[42] Soldiers Died also describes him as ‘formerly 31432 North Staffordshire Regiment’, though this is not confirmed in the MRIC or the Medal Rolls. Soldiers’ Effects shows his widow as ‘Mary E.’

Above: The Pension Record Card for Samuel Bamford

Samuel Bamford was born in 1886, the son of Samuel and Eliza Bamford. He had six siblings, William, Eliza, Lily, Harold, Bertie and Douglas. The family moved around quite a bit, recording addresses in Hanley, Cobridge and Tunstall. By the time of the 1911 Census Samuel Bamford was working as a potter’s handler and living at 37 Nile Street, Burslem, with his wife Mary Ellen (née Holloway), a warehousewoman. Mary Ellen was the daughter of Herbert and Hannah Holloway, who lived at 140 Hot Lane. Samuel and Mary Ellen married on 9 October 1910 at Sneyd Parish Church. A son, Douglas, was born on 8 February 1916. Bamford stated his place of birth as Hanley.

Samuel Bamford’s military service was convoluted. Some of his service files have survived in the Pension Records and among the ‘Burnt Records’. He first joined the army on 18 July 1904, enlisting in the North Staffordshire Regiment’s Militia battalion (Service No. 6220), in which he served for 2 years 102 days. In February 1908 he joined the Regular Army. He applied for Lancers of the Line but was transferred to the King’s (Liverpool) Regiment (Service No. 10214). He does not seem to have liked the Regular Army as he bought himself out on 31 March 1908. Although no record has survived, Bamford appears also to have had another period of service in the 1st Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, which was terminated by his ‘misconduct’ as a mess waiter. This period, without dates, is recorded in his attestation form of 2 September 1914, when he again joined the North Staffordshire Regiment.[43] He was posted to the Depot and then to the 4th (Extra Reserve) Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment in Guernsey. His September 1914 attestation form shows him living at 37 Charles Street, Cobridge. He gave his occupation as ‘teapot handler’, his wife’s name as ‘Mary Ellen’ and his place of birth as ‘Hanley’. On 17 November 1914, however, he was discharged as being ‘unlikely to make an efficient soldier’ after serving just 77 days.

Given this history, it is perhaps surprising that Bamford eventually made it into the army. There is no service file covering his time with the 2/5th Dukes, but his Pension Card shows his service number as 242808, his wife’s name as ‘Mary Ellen’ and her address as 29 Hot Lane.[44] Samuel’s War Gratuity was £3 0s 0d, showing that he had enlisted within 12 months of his death. Given that he found himself in a West Yorkshire based second-line Territorial unit, it is tempting to conclude that he was conscripted, but such a conclusion is probably unsafe.

242808 Private Samuel Bamford, 2/5th Duke of Wellington’s Regiment, has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Arras Memorial, France. BWM; VM.

BARKER, J. 16124 Private John (‘Jack’) Barker, 18th (Service) Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers (2nd South-East Lancashire), who was killed in action on 10 June 1916 aged 24.

18th Lancashire Fusiliers were raised in Bury, Lancashire, by Lieutenant-Colonel G.E. Wike and others as a Bantam battalion on 8 April 1915.[45] They were part of 104 Brigade, 35th Division.[46] On 10 June 1916, in preparation for a raid on the German trenches at Richebourg scheduled for 12.45 am on 11 June, a preparatory excursion was made into No Man’s Land. This failed because of shell fire. Unusually, the battalion war diary lists all those who were killed and wounded, including Jack Barker.

Jack Barker was born in Burslem in 1893. At the time of the 1911 Census he was aged 18 and living at 124 Hot Lane with his father Robert, a coal hewer, his mother Sarah Jane (née Morrey) and his brother Charles, a glaze brick dipper. Jack Barker was employed as a brick setter at the Sneyd Brickworks.[47]

Private John Barkeris buried in Rue des Berceaux Military Cemetery, Richebourg-L’Avoué, Pas de Calais, France. His name also appears on the North Road Memorial, now in Christ Church, Cobridge. BWM; VM.

BOULTON, E. 18591 Sergeant Ellis Boulton, 9th (Service) Battalion Cheshire Regiment, who was killed in action on 4 July 1916, aged 22.

9thCheshires were part of 58 Brigade, 19th (Western) Division. On the day of Boulton’s death the battalion was engaged in the battle of Albert, one of the opening encounters of the Somme campaign. The battalion was pulled out of the line between 3.30 am and 6.30 am on 4 July. After three days of heavy fighting it had lost three officers killed and ten wounded, 25 other ranks killed, 34 missing and 235 wounded.

Ellis Boulton was born in Burslem in 1894, the son of Joseph (1863-1932), a coal miner (hewer), and Emily Boulton (née Jervis) (1861-1913). He was one of five brothers.[48] At the time of the 1911 Census the family were living at 8 Lindley Street, Cobridge. Boulton’s occupation in 1911 was stated as ‘general labourer in aluminium’, presumably at the British Aluminium Company works at Milton.

Sergeant Boulton is buried in Gordon Dump Cemetery, Ovillers-La Boisselle, Somme, France. He was the brother of Joseph and Percy Boulton. His name also appears on the North Road Memorial, now in Christ Church, Cobridge. Kitchener Volunteer: 1914-15 Star; BWM; VM.

BOULTON, J. 9695 Private Joseph Thomas Boulton, 11th (Service) Battalion Manchester Regiment, who was killed in action on 7 October 1915, aged 32.

11th Battalion Manchester Regiment was formed at Ashton-under-Lyne in August 1914. The battalion was part of 34 Brigade, 11th (Northern) Division. At the time of Boulton’s death the war on the Gallipoli peninsula had reached a stalemate, but the battalion war diary reported that sniping was ‘very prevalent’.

Joseph Boulton was born in Burslem in 1882, the son of Joseph (1863-1932), a coal miner (hewer), and Emily Boulton (née Jervis) (1861-1913). He married Betsy Elizabeth Poole at Holy Trinity Church, Sneyd, on 2 November 1902. They had five children: Joseph Samuel (b. 16 November 1903); Florence Maud (b. 12 December 1907); Lincoln (b. 23 March 1909); Agnes (b. 7 June 1911); and Beatrice Ann (b. 28 June 1912). Despite being a married man with a child, Boulton joined the Regular Army on 3 February 1904.[49] He signed on for a 3/9 period of engagement with the Manchester Regiment. He was stationed in South Africa from December 1902 until November 1906. At the end of his three years with the colours, on 2 February 1907, he transferred to the army reserve. When the European war broke out Boulton was recalled and posted to the 2nd Battalion Manchester Regiment (14 Brigade, 5thDivision), in France from 19 September 1914. He was severely wounded by a gunshot to the right shoulder on 25 October 1914 during the Battle of La Bassée. He was evacuated to the United Kingdom and was treated in the 3rd Western General Hospital, Cardiff. After his discharge he was posted to 3rd (Reserve) Battalion Manchester Regiment and then, on 28 August 1915, to the 11th Battalion, which had landed at Suvla Bay on the Gallipoli peninsula on 6 August 1915.

Joseph Boulton worked as a collier (hewer) before and after his pre-war military service. He was the brother of Ellis and Percy Boulton.

Private Boulton is buried in the Azmak Cemetery, Suvla, Turkey. His name also appears on the North Road Memorial, now in Christ Church, Cobridge. Reservist: 1914 Star; BWM; VM.

BOULTON, P. 10658 Private Percy Boulton, 2nd Battalion Irish Guards, who was killed in action on 27 November 1917, aged 18.

2nd Irish Guards was a Regular battalion, part of 1 (Guards) Brigade, Guards Division. On the day of Boulton’s death the battalion was involved in the Capture of Bourlon Wood, during the Battle of Cambrai. On 27 November the battalion attacked behind a creeping barrage, but came under heavy German machine gun fire on reaching a sunken road. Although the battalion took its objectives, casualties were described as ‘very severe’.[50] The level of casualties meant that the captured position was very thinly held and when reports came in that there were Germans in the battalion’s rear, the line fell back to the edge of Bourlon Wood where a defensive flank was formed on the left. At one point the battalion was effectively cut off after severe German shelling and machine gun fire.

Percy Boulton was born in Burslem in 1899, the son of Joseph (1863-1932), a coal miner (hewer), and Emily Boulton (née Jervis) (1861-1913). At the time of the 1911 Census the family were living at 8 Lindley Street, Cobridge. Boulton enlisted on 16 November 1914 as 15428 9th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, giving his age as 18, but was discharged on 16 August 1915 as having enlisted underage. Boulton appears to have been born in the second quarter of 1899. This would have made him 15 in November 1914 and 18 at the time of his death, when he was still underage.[51] He was the brother of Ellis and Joseph Boulton.

Private Boulton has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Cambrai Memorial, Louverval, France. His name also appears on the North Road Memorial, now in Christ Church, Cobridge. Kitchener Volunteer: BWM; VM.

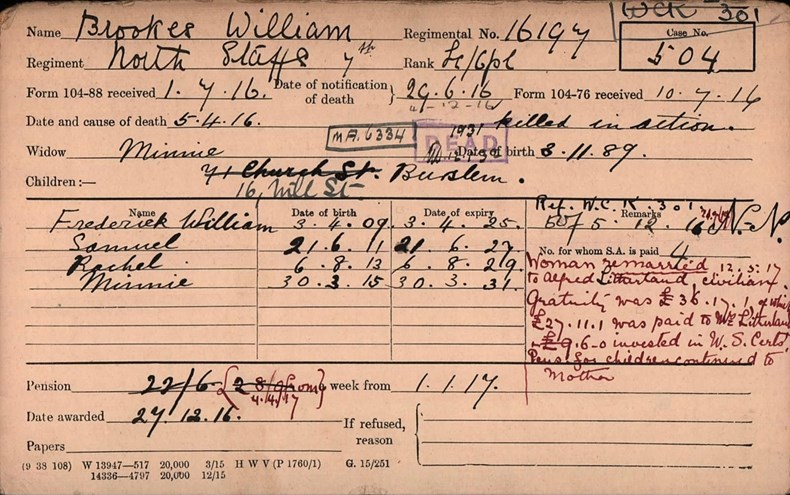

BROOKES, W. 16197 Private William Brookes, 7th (Service) Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, who was killed in action in Mesopotamia on 5 April 1916, aged 26.[52]

On 5 April 1916 39 Brigade, 13th (Western) Division, including the 7th North Staffords, assaulted the Turkish position at El Hanna, the front line of their defence against the relief of Kut-al-Amara, where they had besieged General Townshend’s force since December 1915. The attack was made at dawn and by 6.00 am the whole of the Turkish front line system had been secured. Unfortunately, the brigade pushed too far forward and was caught in a barrage of its own guns (‘friendly fire’). William Brookes was one of 39 other ranks in the battalion to be killed that day. The losses incurred by the battalion during the first two weeks of April 1916 were the heaviest it suffered in Mesopotamia.[53]

Brookes married Minnie Harley in 1907. At the time of the 1911 Census he was living with his wife and son William, aged 2, at 140 Hot Lane, the home of Herbert and Hannah Holloway.[54] He was employed as a miner’s loader underground at Chatterley Whitfield colliery.

Private Brookes has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Basra Memorial, Iraq. His name also appears on the North Road Memorial, now in Christ Church, Cobridge, and on the Barnfields Memorial, formerly in Pleasant Street, but now in St John’s churchyard, Burslem.

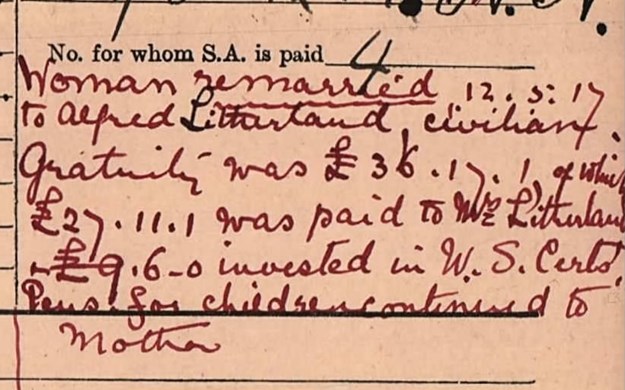

Above: William Brookes' Pension Record Card

Below: The close up of the card which references his widow's re-marriage. Part of the gratuity was paid to the widow, and part invested in War Savings Certificates for the children

Brookes’s widow remarried in 1917, to Alfred Litherland, and lived at 71 Church Street, Burslem. Kitchener Volunteer: 1914-15 Star; BWM; VM.[55]

CAVENOR, F. 75840 Gunner Frank Edward Cavenor, 27 Battery, 32 Brigade, Royal Field Artillery, who was killed in action on 10 April 1917, aged 29.

27 Battery, 32 Brigade RFA was a Regular Army unit that went to war with the original BEF as part of 4th Division. Gunner Cavenor was killed on the second day of the First Battle of the Scarpe, at the opening of the Arras offensive.

Frank Cavenor was born in Burslem in 1888. He married Eliza Donally, brother of William Donally, in 1908. At the time of the 1911 Census they were living at 3 Lower Street, Burslem, with their children, Hilda (aged 1) and Walter Harry (aged six months) and a lodger, Sarah Ann Bates. Cavenor was working as a baker.

Gunner Cavenor has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Arras Memorial, Pas de Calais, France. His name also appears on the Christ Church Memorial. His widow was remarried to Albert Sherratt in 1924 and they lived at 55 Mars Street, Smallthorne. Kitchener Volunteer: 1914-15 Star; BWM; VM.

DONALLY,W. 8671 Private William Donally, 7th (Service) Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, who died of dysentery at No. 3 Canadian Stationary Hospital, West Mudros, on 31 October 1915, aged 19.

7th North Staffords landed on the Gallipoli peninsula on 11 July 1915 as part of 39 Brigade, 13th (Western) Division. The campaign was notorious for health problems, not least dysentery.

William Donally was born in Burslem in 1896. At the time of the 1911 Census he was living with his parents, Edward and Lucy, and his siblings, Charlotte, Albert, Ernest,[56] Charles and Elsbeth, at 37 Moore Street, Cobridge.[57] He was employed as a potter’s handle maker. Donally was the brother-in-law of Frank Cavenor, who married his sister, Eliza in 1908. He volunteered on 1 September 1914, aged 18 years 10 months, by which time he was working as a miner at Sneyd Colliery.

Private Donally is buried in Portianos Military Cemetery, on the Greek island of Lemnos [Limnos].His name also appears on the Christ Church Memorial (Moore Street was in the parish of Cobridge). Kitchener Volunteer: 1914-15 Star; BWM; VM.

FORD, S. 23252 Private Samuel Ford, 3rdBattalion Worcestershire Regiment, who was killed in action on 28 April 1916, aged 21.

3rd Worcesters were part of 7 Brigade, 25th Division. On 26 April 1916 the battalion moved forward from reserve and relieved 10th Battalion Cheshire Regiment in the line about halfway up the slope of Vimy Ridge. The front line ran across a series of mine craters and both sides were engaged in mining and counter mining under fairly constant shell fire. On 27 April the Worcesters established an advanced post on the edge of Broadmarsh Crater. The next day there was sniping and bombing around the new post until about 7:30pm when there was a major explosion caused by the Germans detonating a new mine near the left flank of the battalion’s line. The Germans then attacked and overran the new advance post at Broadmarsh Crater. The Worcesters held the enemy at the crater caused by the new explosion for about four hours until the advance was checked. The battalion suffered six killed, fourteen missing believed killed and one officer and 47 other ranks wounded. It is likely that Private Ford was among the fourteen ‘missing believed killed’.

Samuel Ford was born in Burslem in 1895, the son of Frederick Ford, a boiler maker, and his wife Martha(née Cooper). At the time of the 1911 Census, he was living with his parents and his siblings, David, Eliza and Caroline, at 21 Elm Street, Cobridge, and was a miner by occupation. His service number suggests an enlistment date of June/July 1915.[58]

Private Ford has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Arras Memorial, Pas de Calais, France. Kitchener Volunteer: 1914-15 Star; BWM; VM.

FOSTER, R. 8593 Sergeant Robert Victor McKinley Forster, 7th (Service) Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, who was killed in action in Mesopotamia on 20 April 1916, aged 34.

39 Brigade launched a frontal assault on Turkish positions at dawn on 19 April 1916. This was followed by four days of heavy fighting, during the first of which Sergeant Forster was killed along with 22 other men in the 7th North Staffords. This attack was part of the eventually unsuccessful attempts to relieve General Townshend’s beleaguered army at Kut-al-Amara.

Robert Forster was born in Burslem in 1882, the son of Richard Forster, a potter’s mould maker, and his wife Caroline (née Randles). At the time of the 1891 Census the family, including Robert’s siblings, James W., Reginald, Joshua, Beatrice, Ellis and Frances, were living at 77 Albert Street, Burslem. By the time the war broke out Forster had been married for seven years to his wife, Mary Ann (née Eyres),[59] and they had three children, John Thomas (b. 24 April 1905), Cicely (b. 4 August 1906) and Winifred (b. 27 June 1913). The family lived at 6 Moore Street, Cobridge, and Robert worked as a miner at the Sneyd Colliery. Forster was a veteran of the South African War. He had served for twelve years in the 4th (Extra Reserve) Battalion, North Staffordshire Regiment. On 21 November 1914 he was posted to the 11th (Reserve) Battalion, North Staffordshire Regiment, and appointed Acting Sergeant on 10 February 1915. On 14 September 1915 he was again posted, among a draft of reinforcements, to 7th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, which had been serving on the Gallipoli Peninsula since 11 July.

Sergeant Forster has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Basra Memorial, Iraq. His name also appears on the Christ Church Memorial, where his surname is also misspelled.[60] (Moore Street was in the parish of Cobridge.) Special Reservist: 1914-15 Star; BWM; VM.

HANCOCK, T. Probably 11459 Private Thomas Hancock, 7th (Service) Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, who was killed in action on 9 April 1916 in Mesopotamia. He is the only Thomas Hancock listed in Soldiers Died in the Great War who has a Potteries connection. His name appears to have been carved on the Memorial as an afterthought. No links for him to Elder Road or Hot Lane have yet been documented.

39 Brigade, 13th (Western) Division, including 7th North Staffords, made an attack against Turkish positions at Sanniyat, part of the defences investing General Townshend’s army in Kut-al-Amara. The night was bitterly cold and the troops were ‘hungry, tired and wet’.[61] The attack was made with the bayonet only. The Turks were under good cover and not subject to artillery fire. They met the attack with ‘an absolute inferno of fire’.[62] It should come as no surprise that the attack failed. 7th North Staffords lost 46 men, including Private Hancock.

Soldiers Died gives his place of birthplace and place of enlistment as Burslem, but provides no information about where he resided. HisSoldiers’ Effects file lists his sole legatee as his mother, ‘Mary Jones’.

Private Hancock has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Basra Memorial, Iraq. His name also appears on the North Road Memorial, now in Christ Church, Cobridge. Kitchener Volunteer: 1914-15 Star; BWM; VM.

Above and Below: The Basra Memorial in its original position on the banks of the Shatt al-Arab Waterway, and in its new position (where it was rebuilt under the Saddam Hussein regime in the 1990's) (Photos: CWGC)

HARDING, T. 16070 Private Thomas Harding, 18th (Service) Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers (2nd South-East Lancashire),who died of wounds on 7 November 1916, aged 30.

18th Lancashire Fusiliers were raised in Bury, originally as a Bantam battalion. It formed part of 104 Brigade, 35th Division. At the time of Harding’s death his battalion was holding trenches near Arras. He may well have been wounded on 6 November, when the battalion war diary records ‘casualties’ among NCOs and men following German rifle grenade and aerial torpedo activity. There were no casualties reported on 7 November.

Thomas Harding was born in Hanley in 1886, but at the time of the 1911 Census he was living at 100 Hot Lane, Burslem, with his wife Eliza (née Brockley), a paintress, whom he had married in 1904, and their two children, Charles (aged 4) and May (aged 3). He was employed as a ‘marl miner loader’. (There was a marl hole off Sneyd Street for the Cobridge Brick & Marl Co. Ltd.)

Private Harding is buried in Habarcq Communal Cemetery Extension, Pas de Calais, France. BWM; VM.

HULME, H. 13692 Private Harry Hulme, 7th (Service) Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, who was killed in action on 26 January 1917 in Mesopotamia, aged 26.

7th North Staffords were part of 39 Brigade, 13th (Western) Division. The battalion was transferred to Mesopotamia after the evacuation of the Gallipoli peninsula in January 1916. On 26 January 1917 7th North Staffords were attacking a Turkish position called the Hai Salient, part of the defences of Kut-al-Amara, which was recaptured on 25 February. Harry Hulme was one of 17 men killed on 26 January.

Harry Hulme was born in Burslem in 1891. At the time of the 1911 Census he was living with his parents, Joseph and Elisa [sic] Hulme, at 78 Hot Lane, and was employed as a collier (loader underground), but at the time of his attestation in September 1914 he was employed as an ‘erector’. He married Eliza Machin at St Paul’s Church, Burslem, in October 1912. They had two children, Emma (b. 30 January 1913) and Ellen (b. 21 May 1915). The Commonwealth War Graves Debt of Honour Register describes him as the son of Mrs Eliza Brindley, 122 Hot Lane, Burslem.[63] His widow was remarried to George Chadwick in 1919.

Private Hulme is buried in the Amara War Cemetery, Iraq. His name also appears on the North Road Memorial, now in Christ Church, Cobridge. Kitchener Volunteer: 1914-15 Star; BWM; VM.

HULSON, S.[64] 40741 (also 6627) Private Samuel Hulson, 6th (Service) Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment, who was killed in action on 16 August 1917, aged 31.

6th Lincolns were part of 33 Brigade, 11th (Northern) Division. They were originally employed on Gallipoli, but were redeployed to France in July 1916. On 16 August 1917 the battalion was holding a position called Ferdinand Farm at St Julien, near Ypres. The Germans retaliated with artillery for a machine-gun bombardment being fired by the 33rd Machine Gun Company. Samuel Hulson was one of three other ranks killed by the German shelling.

Samuel Hulson was the son of William and Sarah Hulson, 66 Hot Lane, Burslem. At the time of the 1911 Census he was living with his parents and working as a carter in his father’s business as a ‘metal merchant and rag sorter’. His brother, Gordon, also worked in the family business, but the youngest son, Sidney, was an apprentice fitter at a colliery. Neither brother appears to have served. The family employed a live-in servant, Sarah Lily. Samuel Hulson married Elizabeth Brereton in 1913.

Private Hulson has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Tyne Cot Memorial, West-Vlaanderen, Belgium. His widow lived later at 9 Rose Vale, Chesterton. BWM; VM.

HYDE, J. 37097 Private John Hyde, 2nd Battalion Lancashire Fusiliers, formerly 3/23329, North Staffordshire Regiment, who was killed in action on 11 October 1916, aged 27.

2nd Lancashire Fusiliers was a Regular battalion and had landed in France on 20 August 1914 as part of the original BEF. It was in 12 Brigade, 4th Division. On 11 October the Battalion was on the Somme holding Spectrum and Donald trenches at Trones Wood. The Germans shelled heavily round the battalion HQ, obtaining six direct hits. Four other ranks, including Private Hyde, were killed and 19 wounded.

John Hyde was born in the village of Bradnop, near Leek, in 1889. At the time of the 1911 Census he was living with his parents, James Hyde, a carter, and his wife Ruth (née Harper), together with his siblings, William, Richard, Edward, Martha, Matthew and Ruth, at 4 Sandbach Road, Cobridge. He was employed as a colliery hewer, as were his brothers William and Edward. John Hyde married Annie Hulme in 1912 at Christ Church, Cobridge.

Private Hyde is buried in Bancourt British Cemetery, Pas de Calais, France. His name also appears on the North Road Memorial, now in Christ Church. His widow remarried in 1920 to Samuel Jones and they lived at 25 Hot Lane. BWM; VM

KERRIGAN, J. 9753 Lance Corporal John Kerrigan, 8th (Service) Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, who was killed in action on 17 June 1916, aged 20.

8th North Staffords were part of 57 Brigade, 19th (Western) Division. They landed in France on 18 July 1915. The circumstances of Lance Corporal Kerrigan’s death are obscure. The battalion was training in rear areas in June 1916. There is nothing in the battalion War Diary to explain how Lance Corporal Kerrigan was killed or, indeed, any mention of deaths in the battalion on 17 June. Even so, the Albert Communal Cemetery Extension contains the graves of three other soldiers from the unit who were killed on 17 June 1916, Private W. Grocott, Lance Corporal A. Hancock and Private W. Palfreyman. Another soldier, Private A. Bailey, was killed on 19 June. The 8th Battalion’s history is a bit more helpful:

‘On the 12th June, under command of Major Wedgwood, we left VlGNECOURT with much regret, having had a pleasant time during our stay there. We marched in the direction of the line, halting for one night at MOLLIENSAU-Bois, and on the 13th reached DERNANCOURT, which was found considerably overcrowded. Billets were not available and the Battalion was allotted a hollow near the railway line between DERNANCOURT and ALBERT. With the aid of tents and bivouacs we proceeded to make ourselves as comfortable as the circumstances would allow. A mile and a half away could be seen the shattered church of ALBERT and the now historical feature of the statue of the Madonna hanging over in a horizontal position. Still further could be seen, on the high ground, the chalky outline of the trenches. Ten days were spent in continuous work on the trenches, during which a number of casualties occurred.’[65]

At the time of the 1911 Census Kerrigan was living with his aunt Eliza at 75 Hot Lane and was employed as a ‘taker off at brickyard’, at the nearby Cobridge Brickworks, off Sneyd Street.

Lance Corporal Kerrigan is buried in the Albert Communal Cemetery Extension, Albert, Somme, France. His name also appears on the North Road Memorial, now in Christ Church, Cobridge. Kitchener Volunteer: 1914-15 Star; BWM; VM.

LEWIS, T. 136454 Sapper Thomas Lewis, 171 Tunnelling Coy, Royal Engineers, who was killed in action on 17 October 1917, aged 26.

171 Tunnelling Company was formed of a small number of specially enlisted miners, with troops selected from the Monmouthshire Siege Company RE. First employed in March 1915 in the Hill 60/Bluff areas at Ypres. It moved to Ploegsteert in July 1915 and commenced mining operations near St Yves. April 1916 saw a move to the Spanbroekmolen/Douve sector facing the Messines ridge. At the time of Lewis’s death, 171 Tunnelling Company were road mending near Zonnebeke, Belgium.[66]

At the time of the 1911 Census Thomas Lewis was living with his brother, John, a miner (hewer), and his wife Florence, at 158 Hot Lane, and was employed as a colliery labourer.[67] He married Hannah Johnson in 1913 and they lived at 4 Hale’s Square, Cobridge.

Sapper Lewis has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Loos Memorial, Pas de Calais, France. His name also appears on the Christ Church Memorial.(Hale’s Square was in the parish of Cobridge.) Kitchener Volunteer: 1914-15 Star; BWM; VM.

LIGHTFOOT, D. 3368 Private Daniel Thomas Lightfoot, 3rd Battalion Worcestershire Regiment.

3rd Battalion Worcestershire Regiment was a Regular army unit, part of 7 Brigade, 3rd Division. It deployed to France with the original BEF in August 1914 and was involved in all the early battles: Mons; the Aisne; 1st Ypres.

Daniel Lightfoot’s is a tangled history. He was born in Burslem in 1884, the son of James Lightfoot (1855-1926), a collier, and his wife Elizabeth (née Smith) (1853-1899). In 1891 the family were living at 10 Hot Lane; in 1901 they were living at 14 Elder Road, by which time Daniel was employed as a brickyard labourer. In April 1901, however, he enlisted at Whittington Barracks, Lichfield, in the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion, North Staffordshire Regiment. On 3 January 1902 he transferred to the Worcestershire Regiment. He was recalled to the colours in August 1914 and served with the BEF on the Western Front until he was invalided home in December 1914. He was due to return to his regiment, but his MRIC shows him as having deserted (at home) on 5 October 1915. There is no evidence to indicate that Lightfoot returned to the army or died during the war. He was the brother of John Lightfoot.

For a detailed investigation into Lightfoot’s war, see The Search for Daniel Lightfoot

LIGHTFOOT, J.T. ‘J.T.’ is a mistake. Actually, 38532 Private John William Lightfoot, 4th (Extra Reserve) Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, who died at the Norfolk War (General) Hospital, Blofield, on 17August 1918, aged 38.

John Lightfoot was born in Burslem in 1881, the son of James Lightfoot (1855-1926), a collier, and his wife Elizabeth (née Smith) (1853-1899). He was the brother of Daniel Lightfoot, above. The Lightfoot family were living at 10 Hot Lane at the time of the 1891 Census and at 14 Elder Road at the time of the 1901 Census. After his marriage to Hannah Gertrude Copeland (née Finnemore), on 26 November 1911 at Sneyd Parish Church, the couple lived at 8 Lorne Street, Burslem.[68]

John Lightfoot’s surviving service file shows him ‘attesting’ on 4 December 1915. The date suggests that he ‘attested’ under the ‘Derby Scheme’. During 1915 the voluntary system of military recruitment came under increasing strain and challenge, not only because of its perceived failure to deliver sufficient men for the army but also (and more importantly) because of its evident unfairness and its ill-effects on economic and industrial mobilisation. Despite this, conscription remained unpopular in many quarters, not least the Liberal party. In response, the Earl of Derby, who was appointed Director-General of Recruiting on 11 October 1915, was charged with finding a compromise. The so-called ‘Derby Scheme’ created the basis for a system of conscription – by dividing the male population into 46 groups according to age, marital status, physical fitness and occupation - but without the element of compulsion. Derby was able to do this because he had the data from the National Registration of men and women aged 15 to 65 that took place in August 1915 under the terms of the National Registration Act of July 1915. Under the Derby Scheme men were invited voluntarily to ‘attest’ their willingness to serve if called upon to do so. Married men who attested were assured that they would not be called up until all eligible bachelors had joined the colours. Results were disappointing, but when the War Office announced that conscription would be introduced, recruitment offices were overwhelmed with men wishing to attest. Between 23 October and 15 December 1915, 2,184,979 men attested and 215,431 were enlisted for immediate service. However, 650,000 single men had still not volunteered. Conscription was introduced for single men in January 1916 and for married men the following May.

Although he ‘attested’ in December 1915 John Lightfoot was not ‘enlisted’ until 31 March 1917, by which time he was 36, married and with children, though not in an occupation deemed vital to the war effort. He was posted to the 4th (Extra Reserve) Battalion, North Staffordshire Regiment. Most British infantry regiments had two Regular battalions (1st and 2nd) and a Reserve battalion (3rd). The North Staffordshire Regiment was unusual in having also an Extra Reserve battalion; only 21 other regiments had such battalions. Even more unusually, the 4th North Staffords were deployed on active service in October 1917. Only four other Extra Reserve Battalions shared this fate. The vast majority of reserve and extra reserve battalions were engaged in port protection duties (Forth Garrison, Harwich Garrison, Tyne Garrison, &c). 4th North Staffords landed at Le Havre on 7 October 1915 and served successively with 157 Brigade, 56th (1st London) Division TF (until 9 November 1917), 106 Brigade, 35th Division (15 November 1917 to 3 February 1918) and, finally, with 105 Brigade, 35th Division. This period of the war saw a wholesale reorganisation of the BEF consequent upon the government’s decision to reduce infantry divisions from four brigades to three.

John Lightfoot suffered a serious the gunshot wound to his left thigh on 4 March 1918. On 6 April 1918 the Staffordshire Weekly Sentinel published the following item: ‘PTE. J.W. LIGHTFOOT, MIDDLEPORT. Mrs J.W. Lightfoot, 49, Maddock Street, Middleport, Burslem, has been officially notified that her husband, Pte. J.W. Lightfoot, North Staffs. Regt., has been seriously wounded and is dangerously ill in hospital. Prior to his enlistment he was employed by Messrs. Sadler, Ltd., Newport Street, Dalehall, Burslem.’ [WOUNDED BEFORE THIS] Between 23 and 30 March 1918 35th Division was engaged in repelling the German offensive, which had been launched on 21 March. They were in the Bapaume sector on the Somme. (John Lightfoot had also been hospitalised in January 1918, with dysentery.) Lightfoot really ought not to have been sent into combat in the first place and was very unlucky to have been in one of the very few Extra Reserve Battalions to be deployed on active service. He was hospitalised on 13 April and died on 17 August 1918 from a combination of the effects of the wound and from pneumonia. His family had left their home in Burslem to be with him at the hospital in Norfolk.[69]

Private John Lightfoot is buried in Burslem Cemetery. Derbyite: BWM; VM.

LOVATT, F. Probably 128686 Private Frank Lovatt, 34th Battalion Machine Gun Corps, who was killed in action on 21 March 1918, aged 19.

34th Battalion Machine Gun Corps was the machine gun unit of 34th Division. Private Lovatt was killed during the battle of St Quentin on the first day of the German Spring Offensive.

Frank Lovatt was born in Burslem in 1899, the son of William Lovatt, an engine fitter, and his wife Olive (née Buxton). At the time of the 1911 Census he was living with his parents and his siblings, Harry, Olive, Wilfred, James and Alfred, at 215 Hot Lane. The Staffordshire Weekly Sentinel’s notice of Lovatt’s death, published on 20 April 1918, describes him as having enlisted in ‘August 1915’,[70] at which time he was employed at the Sneyd Colliery. His brother, Corporal Harry Lovatt, also served.

Private Lovatt has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Arras Memorial, Nord-Pas de Calais, France. Kitchener Volunteer: BWM; VM.[71]

MAHON, J. 44455 Private James Mahon, 2ndBattalion Suffolk Regiment,[72] who was killed in action 27September 1918, aged 19.

2nd Battalion Suffolk Regiment was a Regular unit that had formed part of the original BEF, suffering crippling casualties during the battle of Le Cateau (26 August 1914). On the day of Mahon’s death the battalion was part of 76 Brigade, 3rd Division, and was attacking the German defences on the Canal du Nord. On 26 September 1918 the battalion moved to assembly positions at Havrincourt. Its attack began at 5.20 am on 27 September supported by 76 Light Trench Mortar Battery. The battalion war diary comments laconically that there were ‘eleven casualties to other ranks’. The objective was gained.

James Mahon was born in Burslem in 1899, the son of Owen Mahon, a bricklayer’s labourer, and his wife Hannah.[73] At the time of the 1911 Census he was living with his widowed mother (his father died in 1904) and his siblings, Owen (whose name is also on the memorial), Hugh and Mary, and a lodger, William Walley, at 48 Hot Lane.

Private Mahon is buried in Lowrie Cemetery, Havrincourt, Pas de Calais, France. His name also appears on the North Road Memorial, now in Christ Church, Cobridge. (His mother later lived at 9 Moss Street, Cobridge.) BWM; VM.

MAHON, O. 9237 Private Owen Mahon, 9th (Service) Battalion Royal Fusiliers, who was killed in action on 7 July 1916, aged 24.

9th Battalion Royal Fusiliers was part of 36 Brigade, 12th (Eastern) Division. The Royal Fusiliers was a London regiment, but numerous North Staffordshire men served in it.[74] This seems to be the result of the recruiting sergeant in Stoke being a Royal Fusilier! On the day of Mahon’s death the battalion was taking part in the battle of Albert, the first stage of the Somme campaign. On 7 July the battalion was holding trenches in front of Ovillers. Bombardment of the German positions began at 5.30 am, prior to the infantry assault scheduled for 8.30 am. The German artillery retaliated with large calibre guns as soon as the British bombardment began. There were no dug outs in the front trenches and casualties were heavy, especially in ‘C’ Coy. ‘A’ Coy suffered heavily from German machine gun fire once the assault began, but the combined ‘D’ and ‘C’ Coys managed to reach the German trenches, capturing and consolidating the fire and support trenches.

Owen Mahon was born in Burslem in 1893, the son of Owen Mahon, a bricklayer’s labourer, and his wife Hannah. At the time of the 1911 Census he was living with his widowed mother (his father died in 1904) and his siblings, Hugh, James (whose name is also on the memorial) and Mary, and a lodger, William Walley, at 48 Hot Lane. He was employed as a banksman at a colliery.

Private Mahon has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Thipeval Memorial, Somme, France. His name also appears on the North Road Memorial, now in Christ Church, Cobridge. (His mother later lived at 9 Moss Street, Cobridge.) Kitchener Volunteer: 1914-15 Star; BWM; VM.

MILLWARD, E. 38266 Private Ernest Millward, 4th (Extra Reserve) Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, who was killed in action on 12 September 1918, aged 31.

4th North Staffords were part of 105 Brigade, 35th Division. Private Millward was killed during a relief of the 12th Battalion Highland Light Infantry in trenches at St Silvestre Cappelle, a village seven miles north of Hazebrouck in France. His was the only fatality, though four others were wounded. Considerable shelling was experienced during the relief, which led the battalion war diarist to believe that the Germans had ‘anticipated’ it.

Ernest Millward was born in Burslem in 1887, the son of Joseph and Annie Millward, who had lived for many years at 47 Hot Lane.[75] On 29 September 1912 Ernest married Sarah Ellen (formerly Cope, née Proctor). His wife had a son, Frederick Charles Cope, from her first marriage. Millward attested under the Derby Scheme on 1 December 1915, aged 28 years and 10 months, and was immediately transferred to the Army Reserve. His address was then 76 Dartmouth Street, Burslem, and his occupation was given as ‘potter’s turner’. He was mobilized on 26 March 1917 and was posted to France, where he served as a stretcher bearer with ‘B’ Company, 4th North Staffords.

Private Millward is buried at Hagle Dump Cemetery, West-Vlaanderen, Belgium. His name also appears on the North Road Memorial, now in Christ Church, Cobridge. His widow later lived at 6 Peel Street, Longbridge Hayes, and his brother Joseph at 14 Hot Lane. Derbyite: BWM; VM.

PLATT, J. 6078 Private Joseph Platt, 7th (Service) Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, who was killed in action in Mesopotamia on 25 January 1917, aged 39.

Above: Joseph Platt

At the time of Platt’s death the 7th North Staffords, 39 Brigade, 13th (Western) Division, were involved in an engagement known as the Capture of the Hai Salient, part of the eventually successful attempts to recapture Kut-al-Amara. Fighting was intense. Losses amounted to eight officers and 300 other ranks, 99 of whom were killed on 25 January.[76]

Joseph Platt was born in Burslem in 1878, the son of Joseph Platt (1840-1901), a miner, and his wife Mary. He joined the army in 1900, serving in the South African War, where he was awarded the Queen’s and King’s medals. At the time of the 1911 Census he was living at 3 Warburton Street, Burslem, the home of his brother-in-law Matthew Brown, together with his widowed mother, and was employed as a potter’splacer. He was recalled to the colours in 1914, entering a Theatre of War on 10 September 1914 with 1st Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment. At some point he may have been wounded and invalided home before being transferred to the 7th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, a New Army unit.

Private Platt is buried in the Amara War Cemetery, Iraq. His name also appears on the Christ Church Memorial. (Warburton Street was in the parish of Cobridge.) Reservist: 1914 Star & 2 Clasps; BWM; VM.

ROBERTS, P. 201054 Private Philip Roberts, 1/6th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment TF, formerly 4301 North Staffordshire Regiment, who died of wounds on 6 October 1918, aged 30.

1/6th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment was part of 137 (Staffordshire) Brigade, 46th (North Midland) Division. On 3 October 1918 the battalion was following up the huge success it had enjoyed on 29 September, when it crossed the St Quentin Canal at Bellenglise, one of the great feats of the war on the Western Front.[77] Private Roberts suffered a gunshot wound to the head and died three days later at No. 11 Stationary Hospital, Rouen.

Philip Roberts was born in Burslem in 1889, the son of Robert and Sarah Roberts (née Mansfield). Robert Roberts died in 1893 and his widow remarried three years later to Joseph Parker. At the time of the 1901 Census Philip Roberts and his siblings, Robert (aged 17) and George (aged 6), were residing with their mother and stepfather at 25 Greeting Street, Burslem. At the time of the 1911 Census Roberts was apparently married and living with his wife Emily at 22 Acton Street, Hanley.[78] He was employed as a coal miner (loader underground). On 5 April 1915 he enlisted as a Territorial in the 3/5th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment. By then he was living wife his wife and two children, George (b. 8 March 1913) and Elsie (b. 12 September 1914), at 54 Hot Lane. Private Roberts remained on Home service until 24 February 1917, when he was posted to ‘D’ Company, 1/6th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, in France.

Private Roberts is buried in St Sever Cemetery Extension, Rouen, Seine-Maritime, France. Territorial: BWM; VM.

ROWLEY, R. 9295 Private Ralph Rowley, 1stBattalion King’s (Liverpool Regiment), who was killed in action on 27 October 1914, aged 27, at Nord-Westhoek, Belgium.

1st King’s was part of 6 Brigade, 2nd Division. It landed at Le Havre nine days after the expiry of the British ultimatum to Germany, taking part in the battle of Mons, the Retreat, the fighting on the Aisne and the first battle of Ypres. At 3.30 am on 26 October the battalion received orders to clear the village of Nord-Westhoek. The attack began at 5.30 am and was carried out with heavy casualties, including two officers killed and five wounded and 54 NCOs and other ranks killed or wounded. On the day of Ralph Rowley’s death the battalion was subject to heavy German shelling as well as experiencing an infantry assault, which was repulsed.

Ralph Rowley was a constable in the Metropolitan Police when the war broke out, but was recalled to the colours as a Reservist. He had served for eight years in India with the 2nd King’s. The Staffordshire Weekly Sentinel’s notice of his death, published on 5 December 1914, says that he lived formerly at 64 Hot Lane. He was the son of Ralph Rowley (1863-1938), a miner, and his wife Mary Jane (née Morris) (1863-1910). His siblings were Mary, Ada, John, Lily and Walter. In 1891 the family were living at 66 Church Street, Burslem; in 1901 at 1 Herbert Street, Hanley; and in 1911 the widowed Ralph Rowley Snr was lodging at 24 Sandbach Road, the home of William Rowley, together with his daughter Lily and son Walter. On Rowley’s pension card, his father’s post-war address is shown as 18 Hot Lane.

Private Rowley has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Menin Gate Memorial, Ypres, Belgium. His name also appears on the North Road Memorial, now in Christ Church, Cobridge. Reservist: 1914 Star; BWM; VM.

STANDEVEN, J. 27102 Private John Standeven, 8th (Service) Battalion Welsh Regiment (Pioneers), formerly 10451 North Staffordshire Regiment, who was killed in action on 8 August 1915, aged 24,on the Gallipoli peninsula.[79]

8th Battalion Welsh Regiment disembarked at Anzac Cove on 4 August 1915. On 8 August it moved to support the attack on Chunuk Bair being made by the troops who had landed at Suvla Bay. The attacks were driven off by heavy Turkish machine gun fire and snipers. John Standeven was one of four other ranks killed in action on 8 August.

John Standeven was born in Hanley in 1891,[80] the son of George Standeven (1869-1897), a coal miner, and his wife Elizabeth (née Morrey). At the time of the 1891 Census John Standeven, aged 5 months, was lodging with his parents in the home of Thomas Shufflebottom, at 96 Chell Street, Hanley. George Standeven appears to have died in 1897. At the time of the 1901 Census Elizabeth Standeven was living at 2 North Road, with her children John, George (aged 4) and James (aged 10 months).[81] She married John Felton later that year. He died in 1902. So, at the time of the 1911 Census Elizabeth Felton, widow, was living at 86 Hot Lane with her children, John, Elizabeth and George Standeven and Thomas, Ada, Mary and Henry Felton.[82] She also had a lodger, Harriet Shufflebotham. John Standeven was employed as a labourer on a coal pit bank. Elizabeth Standeven was married again, in 1914, to William Ford. She lived later at 98 Hot Lane.

Private Standeven has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Helles Memorial, Turkey. His name also appears on the North Road Memorial. Kitchener Volunteer: 1914-15 Star; BWM; VM.

STEVENSON, I. 7801 Private Isaiah Stevenson, 7th (Service) Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, killed in action on the Gallipoli peninsula on 7 January 1916, aged 28.

At the time of Private Stevenson’s death the 7th North Staffords, 39 Brigade, 13th (Western) Division, were preparing to evacuate the Gallipoli peninsula, an evacuation that was successfully completed on 8 January. The day before, however, the battalion was subjected to a violent Turkish bombardment by high explosive and shrapnel as well as rifle fire and grenades. Attempted Turkish infantry attacks were beaten off. The cost to the battalion was one officer and 34 other ranks, including Private Stevenson, killed and two officers and 56 other ranks wounded. The officer who was killed was the battalion’s CO, Lieutenant-Colonel F.H. Walker.

Isaiah Stevenson was born in Burslem in 1888. At the time of the 1901 Census he was living with his parents, William Henry Stevenson, a miner (hewer), and his wife Mary (née Williams), along with his siblings, Mary, Job, William, Frank, Jonathan and Maria, at 92 Hot Lane.[83] His parents later lived at 16 Abbey Street, Cobridge. Isaiah Stevenson married Margaret McCue in the third quarter of 1912. At the time of Stevenson’s death, she was living at 40 Abbey Street, Cobridge. His widow was remarried to John Carnes in the second quarter of 1919.

Isaiah Stevenson was a reservist, who was recalled to the colours in August 1914, being posted originally to the 3rd (Reserve) Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, prior to his transfer to the 7th Battalion. The Weekly Sentinel notice of his death states that he had two brothers serving: Sergeant W.T. Stevenson, Royal Field Artillery; and Private J. [Job] Stevenson, 3rd Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment. Two other brothers, Frank and Joe, were stated to have attested. Mrs Stevenson also had three brothers serving.

Private Stevenson has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Helles Memorial, Turkey. Reservist: 1914-15 Star; BWM; VM.

SUTTON, J. 11165 Lance Corporal James Sutton, 13th (Service) Battalion Royal Fusiliers, who was killed in action on 11 April 1917, aged 34.

13th Royal Fusiliers was part of 111 Brigade, 37th Division. At the time of Sutton’s death the battalion was engaged in the First Battle of the Scarpe, the first stage of the Battle of Arras. The battalion had been ordered to take the village of Monchy-le-Preux. The attack began at 5.30 am on 11 April. The village was taken despite stubborn German resistance. By 3.00 pm the battalion was entrenched on the western side of the village where it was subjected to heavy German shelling.

James Sutton was born in Tunstall in 1883. At the time of the 1891 Census he was living with his widowed father Thomas Sutton, a baker, and his siblings, Winifred, Louisa and Harriett, at 8 Hot Lane, Burslem, the home of Thomas’s father-in-law, John Steadman. At the time of the 1901 Census Thomas Sutton had married Mary Ellen Barlow and was living with James and his siblings, Winnie and Lucy, together with his step children, Sarah, Harriet, John and Ada Barlow, at 71 Scotia Road, Burslem. By the time of the 1911 Census James Sutton was living at 4 Beardmore Square, Burslem with his wife Winnie (née McQuillan), whom he had married in 1909. He was employed as a potter’s printer and she as a transferrer. They had a baby son, James.

Private Sutton has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Arras Memorial, Pas de Calais, France. His name also appears on the Barnfields Memorial (now in St John's Churchyard).Kitchener Volunteer: 1914-15 Star: BWM; VM.

TUDOR, H. 8661 Private Henry Thomas (‘Harry’) Tudor, 1st Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, who was killed in action on 31 August 1916, aged 34.

Above: Henry Thomas (‘Harry’) Tudor

1st North Staffords were part of 72 Brigade, 24th Division. Private Tudor was killed during heavy fighting in Delville Wood, on the Somme.

At the time of the 1911 Census Tudor was living with his ‘wife’ Laura (née Swingewood),[84] their children, Doris (b. 29 November 1903) and Florence Rachel (b. 27 October 1909), his widowed mother, Mary Griffiths, and his sister, Florence, at 11 Mayer’s Bank, Burslem, and was employed as a ‘jigger in the pit’, probably Sneyd Colliery.[85] On his enlistment documents, dated 26 August 1914,[86] he was living with his wife and another child, Mary (b. 6 January 1914), at 3 Elder Road.[87] He was aged 30 years 6 months and was described as a labourer. He had served in the Militia for six years before the war. On 25 April 1915 Tudor was declared a deserter. On 29 June he was taken into civil custody before being sent back to his regiment. He was tried by District Court Martial on 15 July 1915 and sentenced to one year’s imprisonment.[88] He was released after five months and the unexpired portion of his sentence was expunged on embarkation. He was posted to 1st Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment in France on 8 December 1915.

Private Tudor is buried in Delville Wood Cemetery, Longueval, Somme, France. His name also appears on the Christ Church Memorial. Special Reservist: 1914-15 Star; BWM; VM.

TURNER, W. 46131 Private William Turner, 9th Labour Company, Lincolnshire Regiment, formerly 37958 North Staffordshire Regiment, died as the result of illness on 10 April 1917, aged 34.

William Turner was born in Burslem in 1883, the son of William and Maria Turner. At the time of the 1911 Census he was living with his widowed mother, Maria, at 13 Hot Lane, and was employed as a house painter. The Staffordshire Weekly Sentinel’s notice of Turner’s death, published on 28 April 1917, described him as working for Parker’s Brewery. Turner’s name appears to have been carved on the Memorial as an afterthought.

Private Turner is buried in St Sever Cemetery Extension, Rouen, Seine-Maritime, France. BWM; VM.

VAUGHAN, W. 19069 Private William Vaughan, 6th (Service) Battalion East Lancashire Regiment, who was killed in action in Mesopotamia on 9 April 1916, aged 35.

There is an element of mystery about Vaughan’s unit. Most men who enlisted during the period of voluntary recruitment joined local regiments. Soldiers Died in the Great War gives Vaughan’s place of enlistment as Stoke-on-Trent. There is no evidence of a connection with Lancashire. 6th Battalion East Lancashire Regiment was, however, in the same division, the 13th (Western), as 7th Battalion North Staffordshire Regiment, in which several men on the memorial served, though in 38 Brigade rather than 39 Brigade. On 9 April 1916 the battalion was involved in an action known as the Second Attack on Sanniyat, part of the attempt to relieve General Townshend’s army besieged at Kut-al-Amara.

William Vaughan was the son of Thomas Vaughan, a native of Tipton, described in the 1891 Census as a ‘mill labourer’, and his wife Sarah (née Abberley) (b. 1852).[89] At the time of the 1911 Census he was living with his wife Annie (née Parkinson), a transferrer, and their two children, May (aged 10) and John James (aged 2), at 11 Stoneley Street, Burslem. They had married in 1900. He was employed as a coal miner (hewer). His wife was the daughter of Samuel Parkinson, an engineman, and his wife Eliza, who lived at 10 Adelaide Street at the time of the 1891 census. At the time of the 1901 census William Vaughan and his wife were lodging with her parents at 31 Harvey Street, Burslem.

Private Vaughan has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Basra Memorial, Iraq. Kitchener Volunteer: 1914-15 Star; BWM; VM.

WARDLES, A. Properly 50539 Private Albert Wardle, 7th (Service) Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment, who was killed in action on 19 September 1918, aged 20.

7th Battalion Lincolnshire Regiment was part of 51 Brigade, 17th (Northern) Division. On the day of Private Wardle’s death the battalion was attacking the German positions at Epéhy, part of the Hindenburg Line defences. In two days of fighting (18-19 September 1918) the battalion lost one officer and 21 other ranks killed and 239 wounded, but took its objectives, capturing one field gun, 18 machine guns, 4 minenwerfers[90] and 4 anti-tank rifles, as well as 5 German officers and 160 other ranks.

Albert Wardle was born in Burslem in 1899, the son of John and Elizabeth (‘Lizzie’) Wardle (née Jolley), of 95 Hot Lane. At the time of the 1911 Census Albert was living with his father, a stoker, and his siblings, Jane and Ann (both transferrers), Robert and Edward at 91 Hot Lane. Wardle’s mother died in 1910 and his father remarried, to Jane Stevens, in the last quarter of 1911 (the Census was taken on 2 April 1911).

Private Wardle has no known grave, but is commemorated on the Vis-en-Artois Memorial, Pas de Calais, France. His name also appears on the North Road Memorial, now in Christ Church, Cobridge. Conscript: BWM; VM.

Above: The Vis-en-Artois Memorial