Aerial Photography

- Home

- World War I Articles

- TrenchMapper by The Western Front Association

- Aerial Photography

At the start of the twentieth century the evolution of camera design and photography (fast exposures and camera miniaturisation, automation/remote control and stabilisation) led to two main uses for photographs taken from a tethered aerial platform; survey and observation, both of which had direct military applications. Survey provides the cornerstone of accurate mapping which when overlaid with observations; previous intelligence gathering and reconnaissance, provides military commanders with a two-dimensional representation of the area over which military operations are envisaged or planned.

The first successful experiments in photographic topography were carried out in 1849 by a French army engineer called Aimé Laussedat. Laussedat pioneered the use of aerial photography as a surveying tool to map the city of Paris. He used unmanned balloons and kites from which he suspended his camera. In the mid 1880s E. G. D. Deville, the Surveyor General of Canada, refined and adapted Laussedat’s techniques for use in the Canadian mountains. By comparing the terrestrial photographs taken from various locations and incorporating standard surveying techniques a third dimension was added to the mapping and this resulted in the first accurate contoured maps being produced. Deville’s third dimensional technique was improved in late 1883 when Cornele B. Adams, a US Army officer, was given a patent for a ‘method of photogrammetry’ that involved the capture of two aerial photographs of the same area with a camera from two different positions. The resulting stereo image was then used to create a topographical map. Twenty years before the advent of powered flight the utility of aerial photography in support of accurate map production had been clearly demonstrated.

The use of the nascent aerial photography capabilities was not immediately apparent to many military officers. None of the combatants in the Crimean war (1853-1856), the conflict closest to aerial photography’s birth, appear to have attempted to photograph from balloons. In Britain the War Office could not be convinced of the balloons potential consequently they were not operated at all by the British. The Civil War in the USA was the first large-scale conflict where balloons played a role on both sides. The first reported military application of aerial photography is believed to have occurred in 1862 during the Union siege of Richmond, Virginia. An aerial photograph of the town was taken from an observation balloon. Two gridded map-like prints were produced one for General McClellan, the Union commander, the second for the balloon crew who observed the activity taking place in Richmond from a height of 1,500 feet. Communication was established by telegraph and the balloon observers indicated movements within the town by using a grid marked on the photographs (Hamish B. Eaton, APIS Soldiers with Stereo: An Account of Army Air Photographic Interpretation, (The Intelligence Corps Museum, 1978) p. 1.). A British eye witness to the event, Captain F. Beaumont Royal Engineers (RE), who served with the Union Army’s Balloon Corps in the American Civil War, wrote:

‘I once saw the fire of artillery directed from the balloon; this became necessary, as it was only in this way that the picket which it was desired to dislodge could be seen.’ J. M. Bacon, The Dominion of the Air, (Project Gutenberg Ebook, 1903).

British Balloon Capabilities

Despite the evidence British moves towards balloon acceptance still stuttered. Two officers, Beaumont, and Captain G. E. Grover tried unsuccessfully in 1863 to persuade the British military to recognize the military value of balloons. They failed for two reasons, cost and the operational limitations of not being able to produce hydrogen in the field. However, in 1878, following a change of personnel at the War Office, Captains J. L. B. Templer and H. P. Lee were appointed to the Woolwich Arsenal with the task of constructing and trialing balloons for military use. By 1879 there were five balloons in British military service (Eaton, APIS Soldiers with Stereo. p. 1.).

In 1883, Major H. Elsdale, RE, whilst serving in Canada, made an experimental attempt at balloon aerial photography. Elsdale took photographs of the fortress at Halifax, Nova Scotia using a clockwork-operated plate camera that when an exposure had been taken triggered a mechanism that ripped the balloon fabric and brought the camera back to earth. In 1885 balloons were deployed with the British expedition to Bechuanaland and although Elsdale was present no mention is made of his aerial cameras. Figure 1 is a vertical aerial photograph taken by Elsdale in 1886 of the Balloon School camp at Lydd in Kent.

Figure 1. Balloon School Camp at Lydd in Kent 1886.

A School of Ballooning was formally established at Chatham in 1888, and was moved to Stanhope Lines, Aldershot in 1890 when a balloon section and depot were formed as permanent units of the RE establishment. The Boer war (1899-1902) saw an expansion in British military ballooning with a further four sections, including a photographic reconnaissance section, being authorised and employed in South Africa. The primary roles for the balloon sections was observing enemy troop movements and directing artillery fire. Some of their most important but less published roles was to improve the very poor maps the British had at the outbreak of war, to sketch Boer camps and battle dispositions and take the earliest aerial photographs. Figure 2 is an oblique photograph taken from a British balloon at 1,000 feet. The white patches on the image are smoke from exploding shells.

Figure 2. Boer War - British Camp Balloon Base (date unknown).

The Birth of the Royal Flying Corps

On the 17 December 1903 the Wright brothers flew the first heavier-than-air craft. Another type of aerial platform had become available. In 1908 on a demonstration flight in France Wilbur Wright’s passenger L. P. Bonvillain took the first photograph from an aircraft. The stage was set for a revolution in aerial photography.

The advent of heavier-than-air craft stimulated the British army’s aviation establishment and on 28 February 1911 an army order was issued creating the Air Battalion of the RE’s. The Air Battalion comprised No.1 Company (Airships) and No 2 Company (Aircraft). In October 1911 the British government was provided with a report on the French air corps exercises held at the ‘Camp du Châlons’ during August 1911. The author, Lieutenant Ralph Glyn, was attached to the newly formed Air Battalion. The report cited the main use of aircraft by the French as reconnaissance and control of artillery fire, but went on to highlight the successful use of aerial photography. As the Official History states; in 1911 the French air corps’ exercise provided an insight into:

‘. . . , almost all the uses [for aircraft] which later became the commonplaces of the war’. Walter Raleigh, The War in the Air Volume 1 (Oxford, Clarenden Press, 1922) p. 178.

The obvious importance of aviation and Britain’s perceived vulnerability to air attack led to the creation of a unified British Aeronautical Service called the RFC on 13 April 1912. The RFC comprised a Military Wing a Naval Wing and a Central Flying Training School. By 13 May 1912 the old Air Battalion had been absorbed into the RFC.

Early Aerial Photography in the RFC

During the early summer of 1912 the War Office sought volunteers from across the British Army to join the Military Wing of the RFC as ground personnel. One area that the RFC particularly wanted to improve was in the adaptation of current balloon photographic techniques and methods for use in aircraft. In August 1912 Frederick Charles Victor Laws, aged twenty five, transferred to the RFC from the Coldstream Guards after seven years of military service. He was accepted as an Air Mechanic (photography) 1st Class. Laws was to become one of the key influences in the development of British aerial photography during the First World War. Posted initially to No 1 Airship Squadron at Farnborough where within a few months he was promoted to Sergeant in charge of the photo-section, he soon found that aerial photography was not treated as a priority. Dismayed not to be working with aircraft it was pointed out to him by his Commanding Officer that only airships were involved in photography at that time. The majority of the early photographs were oblique but by mid 1913 the British experience had demonstrated the need for a camera that could be fitted to an airship or aircraft pointing vertically downwards, such a camera would need to be able to take successive vertical photographs that ensured continuity of cover or overlap. During early 1913 Laws had been the camera operator involved in the seminal airship flight that captured an overlapping series of aerial photographs along the Basingstoke Canal. This series of photographs proved a milestone in the application of aerial photography to mapping. The camera used had been the first specially designed and fixed Watson Air Camera (Figure 3).

During the spring of 1913 the Naval Wing of the RFC took control of all the British airships. Laws who was more interested in aircraft than airships asked to remain in the Military Wing and was posted along with his whole photographic section to the Experimental Flight at Farnborough commanded by Major Herbert Musgrave. The unit at Farnborough carried out experimental work with wireless, bombing, photography and artillery co-operation. In the twelve months from the spring of 1913 to 1914 Laws and his photographic team had many flying opportunities and learnt a great deal about emulsions, filters, and the effect of shutter speeds. The greatest challenge was the fitting of the Watson air camera into an aircraft, the first being fitted into a Henri Farman. F. C. V. Laws, Looking Back - Paper read by the Author at the Photogrammetric Society's Meeting on 18th November, 1958, The Photogrammetric Record, Volume 3 Issue 13, (1959) pp. 25-29.

In parallel with the experimental photographic work being carried out by the Flight at Farnborough the aircrew of 3 Squadron RFC, realising the possible value of aerial photography to military reconnaissance work, purchased their own cameras and adapted them for use in the air. The aircrew of the squadron experimented and successfully developed a system of developing the glass plate negatives in the air, so on landing they would be ready to print. During the summer manoeuvres of 1913 the squadron tested their techniques and, early in 1914, produced examples of their work, a series of photographs showing some of the defences of the Isle of White and the Solent. The hand held press-type cameras they adapted and used, with a 6-inch lens, became the camera type used most frequently by the RFC until 1915 (Raleigh, The War in the Air Volume 1. p. 250.).

Netheravon Concentration Camp - June 1914

With the threat of war looming, the RFC gathered in June 1914 at a ‘concentration camp’ at Netheravon, Wiltshire for a trail mobilisation and practice flying, that included aerial photography, over Salisbury Plain. At the end of July, Laws was mobilised and transferred to 3 Squadron at Netheravon. Flying as a passenger in a Henri Farman piloted by Lt. T. O. B. Hubbard he set off from Farnborough to join 3 Squadron with the Watson camera installed in the nose of the aircraft. At 3,000 feet over Odiham the aircraft’s engine failed, forcing a crash landing that wrecked the aircraft and camera but fortunately left Laws and Hubbard unharmed. The RFC had lost its sole aircraft adapted to carry a fixed air camera.

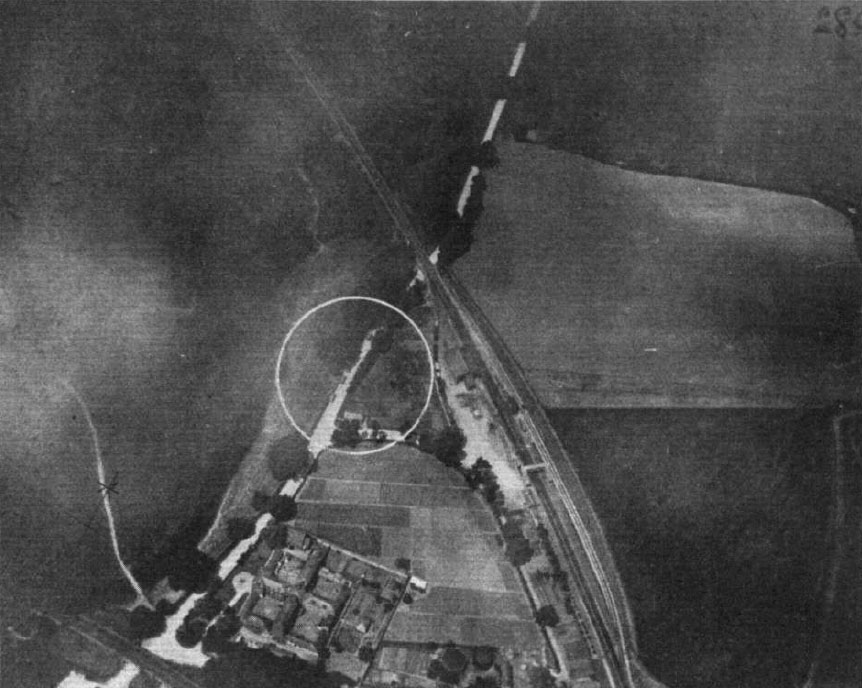

Three days later the art of photographic interpretation within the British military was arguably born. Laws again a passenger in a Maurice Farman aircraft, took photographs using a press-type camera of a parade taking place at Netheravon. When Laws developed the photographs he noticed that he had captured on the photograph a Sergeant Major chasing a stray dog off the parade ground. The tracks of both the dog and the Sergeant Major were clearly visible in the grass, owing to the angle of the light on the crushed blades. (Laws, ‘Looking Back’, pp. 25-29.). Samples of the photographs taken by the RFC during their practice flying were published in Flight Magazine during June and July 1914. Figure 4 illustrates the high quality of one of these photographs, the circle on the photograph highlights four wagons the target of this particular reconnaissance mission.

Figure 4. Reconnaissance target (4 wagons) 15 Jun 14, 2,000 feet.

On the 7 August 1914 Laws left Salisbury Plain for France. He expected to be fully occupied taking photographs of enemy positions, the reality was somewhat different. The RFC that deployed to France, equipped with six hand held ‘Aeroplex’ cameras with 12-inch lenses (up to five ‘Pan-Ross’ cameras followed soon after), had little appetite and arguably little need, at least initially for photography (NA: AIR1/724/91/6/1 History of Photography in the Air Branches, 1914-1918).

The Beginnings August 1914 to January 1916

The early weeks of the First World War were a war of movement, and during this stage the aircraft on all sides performed about as expected, as long range scouts keeping commanders appraised of the enemy’s strategic movements. Following the First battle of the Marne (6-9 September 1914) the character of the war began to change, aerial reconnaissance began to shift from recording movement to surveillance and artillery direction. On 15 September 1914 Lieutenant G. F. Pretyman, a pilot from 3 Squadron, took five photographs of German artillery positions on the Aisne with his own hand held camera (Eaton, APIS Soldiers with Stereo. p. 3.). Although of dubious quality they demonstrated that aerial photography was possible in a combat environment. During First Ypres with aerial photography still failing to impress, sketch maps of enemy trenches and gun pits located by aerial reconnaissance were issued by GHQ intelligence. The stalemate of the trenches brought new challenges to aerial surveillance. Surveillance required repeated flights, over both the immediate front and well to the rear, to detect changes to the German dispositions, and any movement or build-up of forces or logistics. Whilst flights monitoring German rail, road and river movement could be captured by the human eye and noted down the German’s intricately evolving trench systems proved more problematic. Only the camera could provide the definitive view corroborating or correcting the aircrew’s visual observations.

At this stage of the war the impetus for aerial photography innovation rested at the junior officer level. Lieutenant Charles Curtis Darley, a Royal Artillery (RA) officer serving as an observer in the RFC, was the most enthusiastic photographer in 3 Squadron.

‘At first we had, I think, one Aeroplex camera only, and the results were poor, due to fogged plates and being scratched on the film surface due to the metal plate holders. I don't think anyone else in the squadron except myself did any photography at this time. Later Lieutenant E Powell may have taken some. I had to buy my chemicals in Bethune, develop the slides in an emergency darkroom we made up in the stables of the chateau in which we were billeted and send them out.’ (The National Archives, AIR 1/2395/255/1, 3 Squadron notes on aerial photography. 1914 Dec. - 1915 Feb)

During the autumn of 1914 Darley had set up a dark room in the stables of a château where the squadron was billeted and purchased chemicals from Béthune for photographic processing. Initially using his own Aeroplex camera, and then a Pan Ross camera borrowed from a Lieutenant C. D. M. Campbell (who will be discussed later), he slowly collected photographic coverage of the German lines on the Fourth Corps front and following processing painstakingly assembled all the photography to build up a mosaic of the German defence system. On this photographic map he carried out the interpretation and identified and annotated all the salient points of interest, showing the latest developments in the German defensive positions. The mosaic, completed during January 1915, was intended for use by the squadron for planning and reporting purposes but the squadron commander, Major J. M. Salmond, was so impressed that he took it to Corps Headquarters (Eaton, APIS Soldiers with Stereo. p.3.). Darley described the process in his notes:

‘I made a trench map showing all the trenches on our and the enemy sides from the La Bassee - Bethune Road south of the brickfields, including the railway triangle to the north of Neuve Chapelle almost to the Aubers Ridge, which was the limit of the 3 Squadron area. The accurate part of the map finished north of Neuve Chapelle... This I believe was the first trench map and though I made it for my own use as an observer, Major Salmond took it to, I think, Indian Corps H. Q., where it excited considerable interest as shewing the possibilities of aerial photography, and translating the photographs, which were meaningless to most officers, to an intelligible map.’ (The National Archives, AIR 1/2395/255/1, 3 Squadron notes on aerial photography. 1914 Dec. - 1915 Feb)

The mosaic created quite a stir as it clearly illustrated:

‘. . . how the information on the photographs could be reproduced in a form intelligible to all officers.’. H. A. Jones, The War in the Air Volume 2 (Oxford, Clarenden Press, 1928) p. 89.

Here was a picture showing the enemy dispositions that a General could relate to and understand. The detail the photographs provided and their ability to bring the front immediately to the map table made converts of those who where to use it. It would not be long before the interpretation of aerial photographs became an essential element of battle planning.

With the onset of trench warfare and the corresponding change in the tempo of operations, the British corps commanders Generals Haig and Smith-Dorrien began calling for RFC squadrons to be put at their disposal for observation and photography work. When the BEF formally split into two armies on 26 December 1914 the RFC decentralised. By January 1915 it had been split into an RFC HQ and two RFC Wings, comprising of a least two Squadrons and commanded by a full Colonel, each allocated to an Army. First Wing, allocated to Haig’s First Army, was commanded by then Colonel Trenchard. Sholto Douglas a young recently transferred Royal Horse Artillery subaltern continues the story:

‘When I joined 2 Squadron, RFC early in 1915, there was practically speaking no such thing as air photography. I was told that a few photographs had been taken on the Marne by one or two enterprising officers, but these were purely private ventures. However, soon after.... Hugh Trenchard came out to take over 1 Wing, a camera appeared in the squadron, together with a civilian disguised as a Corporal, RFC. This would be sometime in February 1915. The various observers in the squadron were canvassed with a view to finding out whether any of them knew anything about photography. I had a camera as a boy, and had taken, developed and printed some very amateurish photographs. On the strength of this, I was appointed the squadron's official air photographer.’ (Record by S/L. W. S. Douglas of air photography, 1915 Jan. - Mar. AIR 1/2393/240/2)

One of the biggest challenges to overcome was holding the camera steady when being buffeted by the slipstream from the aircraft’s propeller:

‘We found that, by cutting an oblong rectangular [sic] hole in the floor of the observer's cockpit of a BE 2a, the observer could, if he was not too bulky, point a camera downwards between his legs and through the aperture, and thus get a (more or less) vertical photograph. It did not occur to us to fix the camera in the floor of the cockpit; but in any case this would have been impossible, as the camera was of the folding type with bellows.’ (Record by S/L. W. S. Douglas of air photography, 1915 Jan. - Mar. AIR 1/2393/240/2)

Putting the theory into practice proved problematic:

‘We then went up to try and get some photographs of the trench system on our front. I found that the chief difficulty was that when the camera was pointed through the aperture in the floor, one could not see the ground at all, so I had to get my pilot flying on a straight and level course at the object or area that I wished to photograph; hold the camera clear of the aperture until the area to be photographed nearly filled the said aperture; and then pop my camera down into the hole and take a snap shot. This procedure was not too easy in the cramped space available, especially as the weather was cold and bulky flying kit a necessity. Each plate had to be changed by hand; and I spoilt many plates by clumsy handling with frozen fingers.’ (Record by S/L. W. S. Douglas of air photography, 1915 Jan. - Mar. AIR 1/2393/240/2)

RFC Experimental Photographic Section

Coincided with Darley’s initiative, Field Marshal Sir John French received a courtesy copy of some aerial photographs taken by the French air arm and a map on which the German defensive positions had been draw using information derived from the aerial photographs. These photographs were passed via General David Henderson, the commander of the RFC in France, to his Chief of Staff Lieutenant Colonel F. H. Sykes. Sykes had seen some of Darley’s notes on photographic mapping (The National Archives, AIR 1/2395/255/1, 3 Squadron notes on aerial photography. 1914 Dec. - 1915 Feb), and realised that the French were producing better photographs than the enthusiastic amateurs of the RFC. As a result early in 1915 Major W. G. H. Salmond, then a staff officer at HQ RFC, was tasked to liaise with the French photographic organisation. Salmond’s subsequent report outlined a highly centralised technically proficient photographic organisation being operated by the French. As a result of the report, an RFC experimental photographic section was established, by the middle of January 1915, and sent to First Wing which at the time was commanded by Colonel Trenchard. The section commanded by Lieutenant J. T. C. Moore-Brabazon had three other members; Lieutenant C. D. M. Campbell, former Sergeant now Sergeant-Major Laws and 2nd Air Mechanic W. D. Corse. Their role was:

‘. . . to report, after experience in the wings, on the best form of organization and camera for air photography.’ Jones, The War in the Air Volume 2. p. 88.

The new section’s real challenge was to build an aerial photographic intelligence aware military culture. As Moore-Brabazon pointed out:

‘It was exceedingly difficult to get anybody to appreciate what we were trying to do, or use the information we got. In fact Colonel Trenchard carried about with him photographs of the enemy trenches which he pushed before members of the army staff who only viewed them with the mildest interest inspite of the fact that they were planning attacks on the very areas about which we could give them information.’. Medmenham Collection DFG 1471, J.T.C. Moore-Brabazon, Letter to Squadron Leader Mayle, School of Photography RAF, (25 November 1959).

It would take the battle of the Somme in 1916 to finally move aerial photography from a novelty collected by Staff Officers as souvenirs to a pre-requisite for any military operation.

Moore-Brabazon and Campbell set to work on the design of a camera that could be operated in a moving aircraft. The result, the hand held ‘A’ type (Figure 5) manufactured by the Thornton-Pickard company, was first used over the German lines on 2 March 1915.

Figure 5. An ‘A’ type camera being handed to an observer of a FB5. (source: Medmenham Collection)

Operating limitations, the need to lean out of an exposed aircraft cockpit and operate a camera that required eleven distinct operations for the first exposure, and a further ten for each subsequent exposure with thick gloves or numbed fingers, combined with the need for vertical photographs for mapping purposes, led to the fixing of the camera to the aircraft. This was only possible when the key challenges of distortion due to aircraft movement and vibration caused by the aircraft motor necessitating fast shutter speeds, 1/125 of a second, were overcome. By the summer of 1915 when the ‘C’ type camera became available fixed semi-automated aerial photography had been achieved (further details on British cameras can be found in part 5).

Laws and Corse were left to operate the new Wing photographic laboratory that they improvised in a cellar under the châteaux that housed First Wing’s HQ. A process was rapidly established whereby exposed photographic plates were brought in from the RFC squadrons by despatch riders to be developed and printed. As Laws stated:

‘It was not long before a steady stream of prints were being sent to the army formations.’. Laws, ‘Looking Back’, p. 30.

In addition to establishing the Wing photographic laboratory Laws was tasked to train the pilots and observers in First Wing in aerial camera use and was also involved in the design of the A Type camera.

RFC Photographic Sections Formalised

Within the month the experimental photographic section at First Wing was declared a success and following the section’s report recommendation a photographic section was established at the HQ of each of the now three RFC Wings. The original photographic section was tasked with creating and training the new sections at the other two Wings. The new photographic sections were commanded by an RFC ‘Equipment Officer’ who was responsible for all aspects which included camera technical issues and aircrew instruction in the use of cameras. The centralisation of the photographic processing and printing at Wing level streamlined the RFC’s aerial photography processes ultimately widening the dissemination of the raw printed photograph (A ‘raw’ photograph is a photograph issued unanalysed, having yet to go through an interpretation process). The centralisation also provided another key benefit; each photographic section was charged with maintaining their Army’s History of [photograph] Coverage (HOC). The HOC comprised a record of every exposed negative which was to include; the negatives unique number, the exposure date, time and place, the exposure altitude, the atmospheric and light conditions, the shutter speed and photographic stop used. The outline of each photograph was plotted on a map and cross-referenced to a card index file system (Finnegan, Shooting the Front, pp. 46 - 47). A comprehensive, coherent and searchable HOC would prove pivotal in realising the potential of photographic interpretation; it would not be long before HQ’s at most levels began keeping records and copies of the aerial photographs that covered their areas of interest. What was lacking though was a process that facilitated an understanding of what the photographs contained. Gone was the ad-hoc approached practiced by Darley who had spent many hours at Division and Corps HQ pointing out and explaining the detail visible in his photographs to uninitiated Staff Officers. The scale of the new photographic operation made the personal approach that much more difficult. Recipients had to develop their own photographic interpretation skills and as a result during much of 1915 many recipients viewed aerial photographs as little more than very accurate maps.

The New Intelligence Source

One of the beneficiaries of this new intelligence source was Lieutenant Colonel J. Charteris, General Staff Officer (GSO) I Intelligence at First Army HQ. Aerial photographs had been coming into First Army Intelligence in slowly increasing numbers since the start of the year. In a diary entry dated February 24 1915, probably during the planning for the battle of Neuve Chapelle, he wrote:

‘My table is covered with photographs taken from aeroplanes. We have just started this method of reconnaissance, which will I think develop into something very important.’. John Charteris, At G. H. Q. (London, Cassel &Company, 1931). p. 77.

At this stage of the war the mapping of areas behind the German lines was the responsibility of the Intelligence staff. The techniques of revising detail and plotting German defences from aerial photographs onto the available maps had been developing over the previous months and by the end of February the RFC’s pioneering photography work coupled with Laws’ camera training had enabled First Wing, presumably mainly Darley and Douglas to photograph the entire German trench system in front of First Army to a depth that ranged from 700 to 1,500 yards. The result was a fairly complete picture of the German tactical dispositions. This tactical picture, which was regularly updated, was used by Haig to plan the Battle of Neuve Chapelle. Significantly photographic interpretation inputs from Darley prompted modifications to First Army’s attack planning (J. Laffin, Swifter than Eagles: A Biography of the RAF, Sir John Salmond (London: William Blackwood, 1964), p.60-61.) Additionally 1,500 copies of a 1:5,000 scale map, derived from these photographs, overlaid with an outline of the German defensive system were specially printed and issued to each of the attacking Corps (Figure 6). Crude compared to later standards (see Figure 8) the maps represented the first true Common Operating Picture (COP) ever taken into battle by a modern British army.

First Army was the first to recognise the real utility of aerial photography for intelligence purposes: ‘in spite of limitations, aeroplane photographs are, at the present state of proceedings, by far the most reliable evidence we get of alterations in the enemy’s line and indications of his future moves’. No.32 ‘IM’, First Army to Moore-Brabazon, 1 June 1915, Box 87, Moore-Brabazon Papers, RAFM

Figure 6. Neuve Chapelle 1915. (source: H. A. Jones, The War in the Air Volume 2 (Oxford, Clarenden Press, 1928) between pp. 90-91.)

Artillery Driven Synergy of Ground Survey, Cartography and Aerial Photography

Although a resounding success the Neuve Chapelle battle map was not the trigger that moved aerial photography from the status of novelty to indispensability. From late 1914 through all of 1915, the British Army experienced a critical shortage of artillery ammunition. This shortage drove the introduction of artillery survey; battery positions and targets needed to be fixed to a survey grid so that rounds used for target ranging and registration could be kept to a minimum. From early 1915 an artillery driven synergy of ground survey, cartography and aerial photography which resulted in the production of maps on which German positions and activity could be accurately plotted and subsequently targeted was begun.

The first use of a squared map prepared by Lieutenant D. S. Lewis of the RFC was noted in September 1914 during the initial attempts to control artillery fire from the air using wireless (Jones, The War in the Air Volume 2, p. 85.). By the end of 1914 the squared map system had been accepted and adapted and covered the whole of the British front. The co-ordinate system used allowed positional locating accuracy down to approximately five yards, assuming that the base mapping was accurate. It was soon recognised however that the Army Intelligence Sections lacked the necessary skills to produce mapping to the required levels of detail or accuracy.

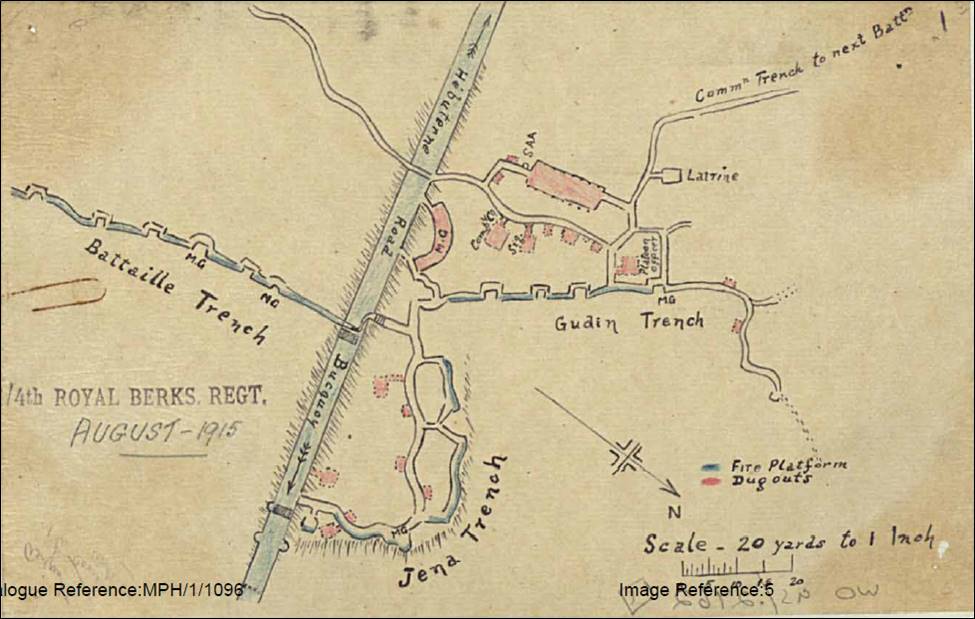

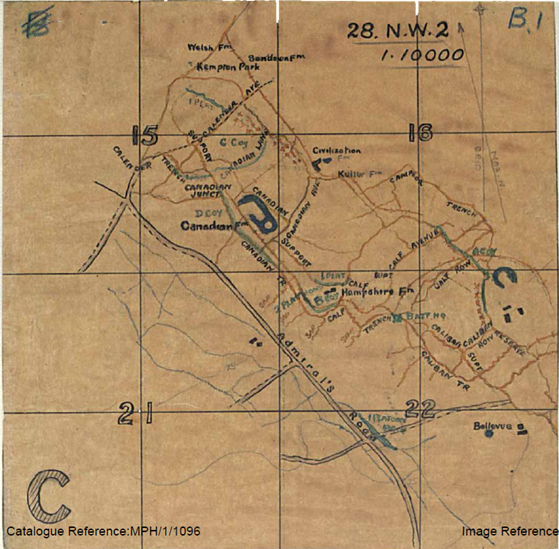

Figure 7. Hand drawn by ‘Intelligence’ - (source: National Archives extracted from WO 95/2762.)

So between July and September 1915 Topographical Sections were created at Army level. These sections were responsible for all survey work, map supply and reproduction in their Army area. This included the production of trench mapping from aerial photographs.

Figure 8. First generation 1:10,000 trench map - (source: National Archives extracted from WO 95/2762.)

The transfer of ‘maps and printing’ from Army Intelligence to the Topographical sections was not seamless. According to Capt Carrol Romer, the officer in charge of First Army’s Maps and Printing Section in early 1915, who has been credited as the first British photographic interpreter whilst serving under Charteris (Charteris, At G. H. Q.. p. 82.):

‘Masses of information of all sorts is collected at great labour and expense and it all goes onto a file and there it is comfortably and peacefully disposed of.’ Romer diary, quoted in: (Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers,p. 86.)

Romer was referring to perceived shortfalls in the effective compilation and dissemination of counter-battery intelligence during the transfer. Whilst the Army Intelligence Sections remained the authority on the strength and dispositions of the enemy the topographical evidence supporting that intelligence, much of it derived from the ever increasing numbers of aerial photographs, had to be plotted accurately onto the map. As a result the bulk of the photographic interpretation work shifted to these new Army Topographical Sections with any ambiguities being referred to ‘Army Intelligence’ for clarification. By the end of 1915 Third Army’s Topographical Section, at the request of the Army Staff, had begun to include the German trench system, including barbed wire, and known German artillery battery positions as overlays on the newly created 1:10,000 map sheets.

Uneven Development of Photographic Interpretation Skills

Despite this cartographically driven shift, the ever increasing number of aerial photograph recipients in the army’s subordinate formations continued an ad-hoc and uneven development of their photographic interpretation skills. During the summer of 1915 Alan Lloyd was appointed as an intelligence officer on the staff of First Corps where he was made responsible for the Corps aerial photographs ‘. . . which at the time, were merely regarded as very accurate maps.’ (Medmenham Collection DFG3412, Letter Lloyd to Babingdon-Smith, 3 Dec 1957.). In November 1915 Lloyd gave a lecture on aerial photographs to his Corps Commander which proved such a success that he was ‘sent round troops at rest to teach them how to read their photographs.’ (Letter Lloyd to Babingdon-Smith, 3 Dec 1957.). Lloyd went on to produce a series of notes to support his photographic interpretation lessons that were ultimately sent to GHQ, via Corps and Army, and were reproduced as the first British photographic interpretation guide ‘S.S. 445 Some Notes on the Interpretation of Aeroplane Photographs’ in November 1916 (The National Archives, AIR 34/735, Some Notes on the Interpretation of Aeroplane Photographs (December 1916). Referenced in ‘S.S. 550 Notes on the Interpretation of Aeroplane Photographs’, March 1917.). In contrast the Canadians appeared to have had a far greater awareness of the utility of aerial photographs during 1915:

‘A German aeroplane has been hovering over our positions looking for my gun, so we have stopped firing and all movement. I know just how the chicken feels when the hawk hovers over it. Few people realize how much aeroplanes figure in this war, for war would be much different without them. They do the work of Cavalry only in the sky. Whenever they come over, the sentries blow three blasts on their whistles and everybody runs for cover or freezes; guns stop firing and are covered up with branches made on frames. If men are caught in the open they stand perfectly still and do not look up, for on the aeroplane photographs faces at certain heights show light; dugouts are covered over with trees, straw or grass. We use aeroplane photographs a great deal; they show trenches distinctly and look very like the canals on Mars.’ Louis Keene, “Crumps” The Plain Story of a Canadian Who Went, (Boston and New York, Houghton Mifflin Company, 1917) pp. 83-84.

When the Canadian Corps formed in September 1915 they established a new GSO, Second Grade, to command the intelligence service within the Corps. This officer had under his command:

‘. . . a small force of draughtsmen and assistants working on aeroplane photographs, which were then beginning to be used extensively . . .’. J.E. Hahn, The Intelligence Service within the Canadian Corps 1914-1918,(Toronto, Macmillan, 1930) p. xviii.

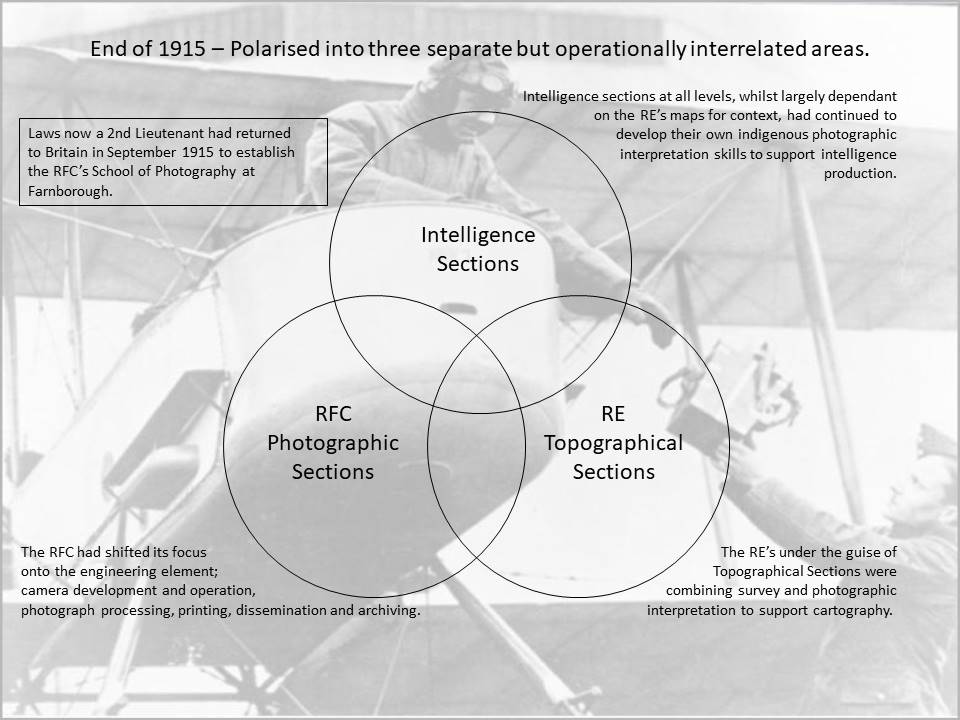

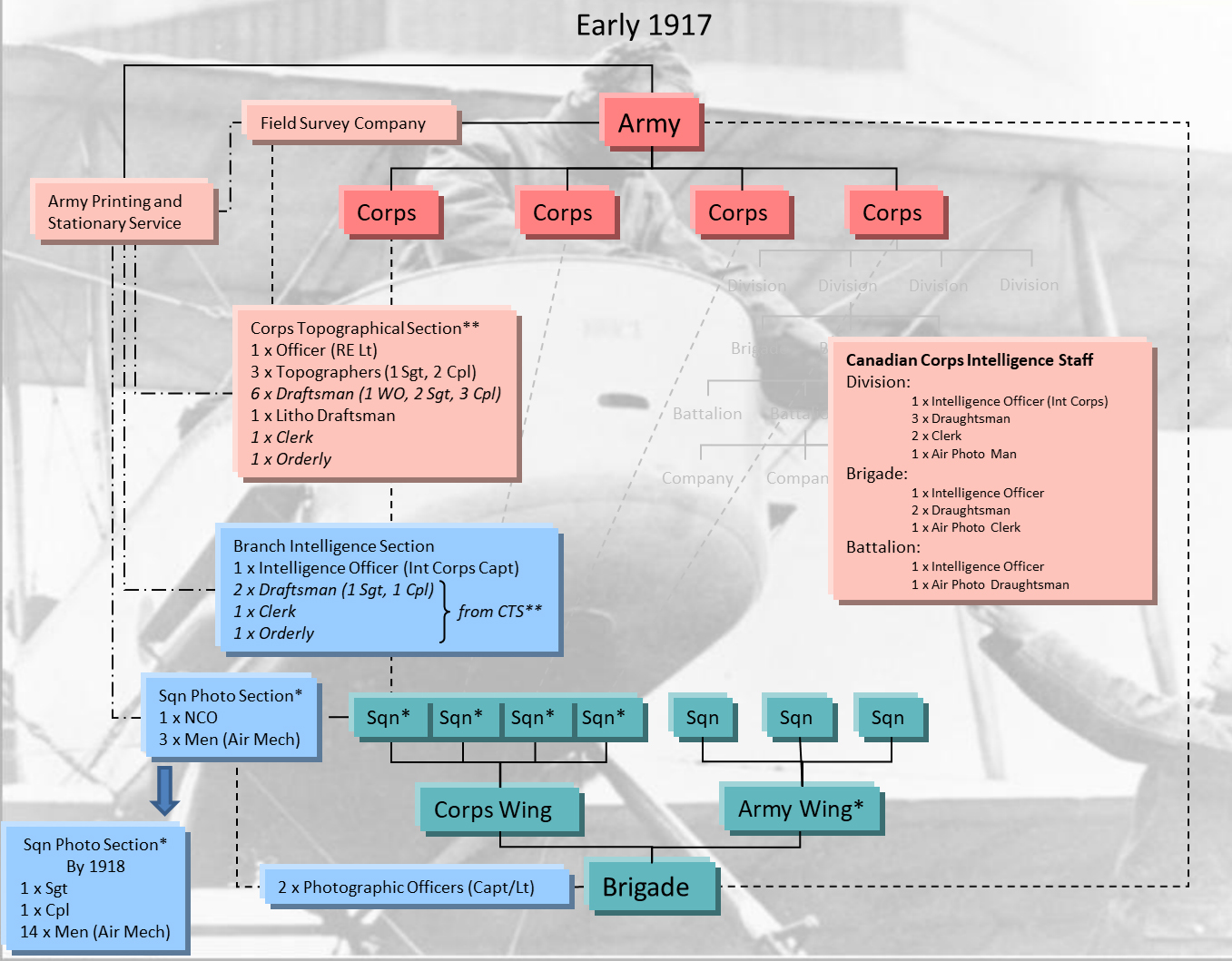

By the end of 1915 aerial photography had polarised into three separate but operationally interrelated areas (Figure 9). The RFC had shifted its focus onto the engineering element; camera development and operation, photograph processing, printing, dissemination and archiving. Laws now a Second Lieutenant had returned to Britain in September 1915 to establish the RFC’s School of Photography at Farnborough. The RE’s under the guise of Topographical Sections were combining survey and photographic interpretation to support cartography. Intelligence sections at all levels, whilst largely dependent on the RE’s maps for context, had continued to develop their own indigenous photographic interpretation skills.

Figure 9. Aerial photography had polarised into three separate but operationally interrelated areas.

Aerial Photography comes of age

Kitchener’s Volunteers – a new RFC Structure

The arrival late 1915 and early 1916 of Kitchener’s volunteers changed the BEF into a mass army forcing another change on the growing RFC. A new command structure was required to cater for a planned 60 service and 20 reserve Squadrons. This was outlined in two Army Council letters dated 25 August and 10 December 1915:

‘The RFC in the Field, currently divided into three wings, each attached to an army headquarters, was to be reconstituted as a brigade. As fresh units became available, new brigades were to be formed until there was one for each of the BEF’s armies. It was originally planned that each brigade would comprise three wings, but in the event there were only two until the middle of 1918. One, designated the Corps Wing, was for general [Corps level] co-operation duties; the other, designated the Army Wing, was for army reconnaissance, bombing and air fighting duties.’. Malcolm Cooper, The Birth of Independent Air Power (London: Allen & Unwin, 1986), p. 33.

The new Brigade formation came into effect on 30 January 1916 and by the start of the Somme there were four RFC brigades, one for each army, and a Headquarters Wing attached directly to GHQ. Under the new organisation each Corps now had an attached RFC squadron under its control and the Corps staffs were responsible for photographic reconnaissance tasking along the Corps front up to a depth of 5,000 yards. Beyond this aerial photography was the responsibility of the Army Wing.

Decentralisation of Photograph Reproduction

By the spring of 1916 the demand for photographs was overstretching the capabilities of the Wing photographic sections causing unacceptable delays in print delivery to demanding units. The solution enacted in April 1916 was to decentralise and establish a small photographic section, comprising a non-commissioned officer (NCO) and three men, at each of the Corps squadrons and in each Army reconnaissance squadron. Additionally each RFC Brigade was established with two RFC Photographic Officers, one notionally located at the Corps Wing the other at the Army Wing.

The training for the new photographic sections was carried out at Farnborough and included; the use and maintenance of aerial cameras, developing and printing plates, print titling and enlargement, the production of photograph mosaics, map reading and plotting. The role of these new sections was therefore camera maintenance, photographic processing and print production. As Laws describes:

‘ [On landing] . . . the plates where rushed into a darkroom on the squadron, processed and printed. . . . the first prints went to the local army headquarters, brigades, and sometimes down to company commanders. Then the negative would go back to the wing. They would make a distribution to the higher armed formations.’. Frederick Laws, quoted in: Joshua Levine, On a Wing and a Prayer, (London, Collins, 2008), p. 136.

Continued Uneven Development of Photographic Interpretation Skills

The interpretation of the photographs was being done elsewhere in intelligence sections by the recipients of the prints, many of whom had limited or no photographic interpretation experience. The Army Topographical sections had expanded and were subsumed within newly created Field Survey Companies (FSC) in February 1916. Each Army had its own Field Survey Company that was responsible for; fixing the position of British artillery batteries, Map drawing and distribution, Observation and flash spotting, sound ranging, and counter battery intelligence compilation. Within the organisation of a FSC was a Compilation section that had the role of synthesising the artillery counter-battery intelligence at army level. By this stage of the war each Army had a Staff Officer designated to study air photographs, within Third Army the officer was a Lieutenant Goldsmith. Goldsmith described as ‘one of the pioneers in the scientific study of air photographs’ was a compiling officer in Third Army’s Compilation Section (H. H. Hemming, Private Papers of H H Hemming, IWM Catalogue Number 12230 PP/MCR/155.). One of his stated duties was:

‘To study the interpretation of air photographs, and to that end the system and type of enemy works.’. H. Winterbotham, Survey on the Western Front (Provisional Report), (Maps, GHQ, 20 Dec 1918) p. 42.

By comparison in August 1916 Francis Law, an Irish Guards infantry officer being given a rest from the front, reported to Headquarters IXth Corps. His role for two months was as the Corps artillery intelligence officer where one of his jobs was the interpretation of aerial photographs. He was one of many officers with no photographic interpretation or intelligence experience assigned temporarily by Charteris to intelligence duties during 1916 (Francis Law, A Man at Arms (Collins, London, 1983) pp. 73-75.). Both the BEF and its intelligence requirements had expanded exponentially leaving Charteris with little choice.

Aerial photography over the Somme

Aerial photography over the Somme area had begun well before July. By the end of May 1916 the German first, second and third line defensive system had been photographed to a depth of more than 20 miles, and during the preliminary bombardment the first and second German lines were photographed again to determine how effective the British bombardment was. Throughout the Somme aerial photography was continuously asked for. The GSO 2 Intelligence of the First ANZAC Corps stated in his diary that he:

‘. . . was kept very busy [along with his other intelligence officers] interrogating prisoners, studying air photo’s, map making, issuing daily Intelligence Reports and so on.’. S. S. Butler, Private Papers of S S Butler, IWM Catalogue Number 9793 PP/MCR/107.

Photographic Intelligence Reporting

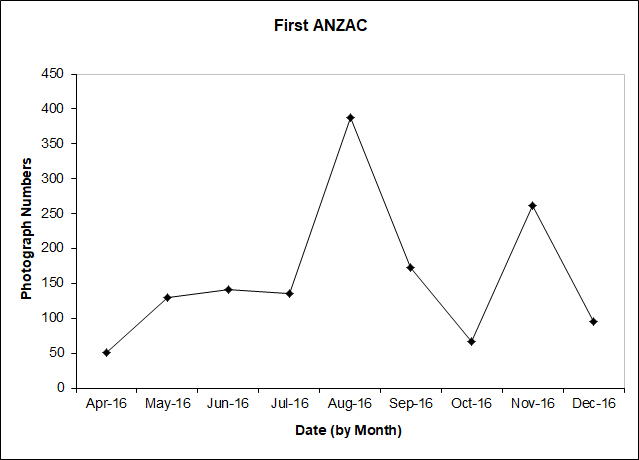

The increase in availability of aerial photography can be clearly discerned in the First ANZAC Corps intelligence summaries (INTSUMS) written during 1916.

Figure 10. Numbers of aerial photographs available to First ANZAC Corps 1916. (source: AWM4-1-30)

Figure 10 provides a monthly summary of the number of aerial photographs listed as available to the Corps in the Corps daily INTSUMS. The obvious peak in photograph numbers, August 1916, correlates to the battle of Pozières (23 Jul - 3 Sep 1916) in which First ANZAC Corps were heavily engaged whilst the second peak in November correlates with the First ANZAC Corps attacks at the close of the Somme battle in the area near Gueudecourt and Flers. In addition to the quantitative increase in the availability of aerial photography during the Somme campaign, what could also be discerned from the INTSUMS was a qualitative increase in the extraction of the photographic intelligence.

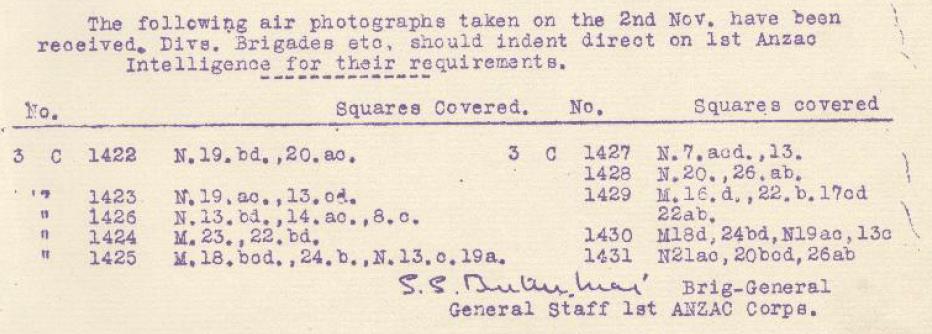

Figure 11. Photograph ‘Shopping List’. (source: AWM4-1-30)

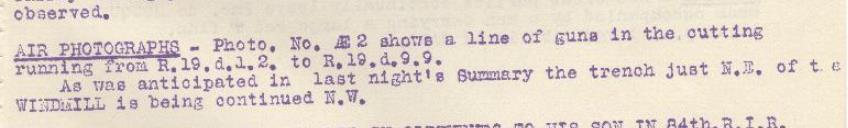

During April and May 1916 the INTSUMS provided little more than ‘shopping lists’ of available photographs that could be ordered by subordinate units from First ANZAC Corps intelligence (Figure 11). From June onwards every two or three days the INTUMS started to contain textual summaries outlining the activity observed on the photographs taken in the intervening period. Between June and early November the fidelity of the reporting also changed, simple trench construction updates changed to include summaries of track usage, resupply choke points worthy of artillery attention, and the location of possible German headquarters elements.

Figure 12. Textual summaries outlining the activity observed on the photographs. (source: AWM4-1-30)

From late November the textual summaries were provided alongside the list of photographs they related to, usually in the INTSUM the day after the photograph was taken (Figure 12).

By the close of the Somme intelligence updates based on aerial photography were provided down to Brigade level in First ANZAC Corps. At the top of each INTSUM it stated ‘NOT TO BE TAKEN FURTHER FORWARD THAN BRIGADE HEADQUARTERS’. Further downward dissemination relied on the developing intelligence structures at Brigade and Battalion level. In comparison the daily INTSUMS issued by Second ANZAC Corps during the Somme period contained ‘shopping lists’ of available photographs and at the end of each month a textual summary of the German trench construction noted on aerial photography during the preceding month. Second ANZAC had arrived in France during July 1916 and held a quiet section of the line near Armentières north of the Somme area by the Belgian border. The lack of detail in their intelligence reporting is more likely a reflection of the operational tempo being experience by the Corps rather than an indictment on the skills of the Corps photographic interpretation specialist.

TCPED Incoherence and Duplication

From July to November 1916 the RFC took over 19,000 aerial photographs from which approximately 430,000 prints were made (Eaton, APIS Soldiers with Stereo, p. 6). In general terms this equated to approximately 22 copies of each photograph being produced and distributed.). The ever increasing volume of aerial photography exposed incoherence and duplication in the BEF’s aerial photography Tasking Collection Processing Exploitation and Dissemination (TCPED) processes.

Intelligence Specialists at Squadron Level

Early in 1916 the RFC had realised that it was not making full use of the intelligence collected or assimilated by its aircrew. From mid 1916 Recording Officers (RO’s), of Captain/Lieutenant rank, began to be appointed in RFC squadrons. The RO’s acted as intelligence officers and the squadron Adjutant and were tasked with debriefing aircrew collating the information gathered and forwarding anything of value to headquarters. In addition the RO’s in the Corps squadrons took on the artillery and infantry liaison role to reduce the burden on the Squadron Commanders (Hughes, ‘Diary’ of T McK Hughes.). The appointment of RO’s was recognition of the need for an intelligence function at squadron level. Despite this initiative the sheer volume of information generated during 1916 coupled with a parochial view taken by many squadron RO’s, largely caused by a lack of formal intelligence training, meant that a wealth of intelligence information was just carefully filed. The RFC had wanted to call its RO’s ‘Intelligence Officers’ but GHQ Intelligence had refused to sanction the name or the role and was adamant that such a role would fall under the purview of the intelligence staffs.

A British study of the French intelligence system published in September 1916 highlighted the advantages of integrating an intelligence specialist at squadron level (The National Archives, WO 158/983, Notes on the French system of intelligence during the battle of the Somme (September 1916).). With this study in mind in October 1916 Trenchard, now the Major General in command of the RFC in France, proposed that intelligence sections be established at squadrons and wings with reconnaissance and photographic responsibilities ‘where the Intelligence Officer could be in intimate touch with the flying and photographic personnel’ (H. A. Jones, TheWar in the Air Volume 3 (Oxford, Clarenden Press, 1931) p.315.). From late October an experimental intelligence section commanded by Captain G. T. Tait, an attached Intelligence Corps officer, was established at 3 Squadron RFC, the squadron subordinated to First ANZAC Corps during the latter stages of the Somme (Australian War Memorial, Honors and Awards - Gerald Trevredyn Tait, (25 Dec 1917)). The experiment was deemed a success, and during December 1916 instructions were issued to form Branch Intelligence Sections (BIS’s) at the headquarters of each corps squadron and each army wing. The BIS’s, commanded by an Intelligence Corps Officer called a Branch Intelligence Officer (BIO), comprised; two draughtsmen, one clerk and an orderly. The sections role was clearly defined:

‘To interrogate every observer and ensure that full advantage be taken of such information as he might possess.

To disseminate to all concerned with the least possible delay information obtained by the Royal Flying Corps which required immediate action.

To examine and, where necessary, to mark all photographs and to issue both photographs and sketch maps illustrating the photographs.’. Jones, The War in the Air Volume 3. p.315.

The Official History states that: ‘Although the sections formed part of the Army or Corps Intelligence they were placed under the direct orders of the officer commanding the wing or squadron . . .’. Jones, The War in theAir Volume 3. p.316.

The reality may have been different. Lieutenant Thomas Hughes, the BIO attached to 53 Squadron in 1917, shows clear animosity towards his Squadron Commander in his diary. His refusal to comply with his Squadron Commander’s order relating to situation maps and his deference to Corps Intelligence guidance would suggest that the BIS’s came under the purview of GS Intelligence (Hughes, ‘Diary’ of T McK Hughes.). During 1917 there was a trend in some Corps to publish a daily situation map as part of their daily INTSUM. The situation maps were an RFC driven initiative and in the participating corps were produced by the BIS. Hughes an experienced photographic interpreter was sceptical about the value of these maps, his scepticism centred on accuracy and production time. Produced at 1:20,000 scale and annotated with activity derived from aerial observation and photography they presented a quick visual update unsuitable for determining accurate positional data. In Hughes’ opinion the intelligence content also suffered. A review of the II ANZAC Corps INTSUMS during 1917 supports this view, INTSUMS issued with a situation map contained limited aerial photograph derived textual updates.

Corps Topographical Sections

Much to the chagrin of the RE’s, with the exception of the Intelligence Corps Officer, the manpower for the BIS’s came from the newly forming Corps Topographical Sections. Raised as an integral part of the FSC’s they were subsequently detached to Corps Headquarters where they worked under the immediate direction of the GS Intelligence. During the Somme the need for rapid dissemination of information about the constantly changing tactical situation had led to the devolution of certain aspects of map production from Army to ad-hoc topographical sections at corps level (Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers. p. 224.). Although not officially authorised until January 1917 the first Corps Topographical Sections appeared in Fourth Army in December 1916. The RE’s had their own view on the role of the BIS’s:

‘Branch Intelligence Sections had been formed about the same epoch [as Corps Topographical Sections], and for some time there was considerable overlapping of work, and doubt as to their exact relative spheres. The Branch Intelligence Section was instituted for the information of the Royal Flying Corps Pilots themselves, rather than for the reproduction and sketches for Corps and Divisional Troops. The latter duty falls to the Topo Section.’. Winterbotham, Survey on the Western Front. p. 50.

In direct contradiction to the RE’s perception the Canadian Corps viewed the utility of the BIS’s differently:

‘One of the most important functions [of the BIS] is the examination of aeroplane photographs, interpreting them with respect to topography in the enemy’s country, as well as annotating works and defences prior to their issue.’ Hahn, The Intelligence Service within the Canadian Corps 1914-1918. p. 260.

The ‘Branch Intelligence Officer is a Canadian Corps Officer who lives with the Squadron of the R.A.F. covering the Corps front, and with whom the Intelligence Branch communicates if they wish any particular mission carried out by the R.A.F. This officer is further an expert in Aeroplane Photographs, and transmits any information he may glean at the Squadron Headquarters to Intelligence Branch at Corps Headquarters.’ REPORT of the MINISTRY, Overseas Military Forces of Canada 1918. p. 217

Synergy between BIS and Corps Topographical Section

In reality the functions of the BIS’s and Corps Topographical Sections complemented each other. The BIO at the BIS was the conduit through which all the Corps aerial reconnaissance and photography tasking flowed. His unique position gave him oversight of the Corps operation intelligence requirements thus enabling him to quickly prioritise intelligence gleaned from aircrew debriefs, reconnaissance reports and his section’s photographic interpretation efforts. Time critical intelligence was disseminated immediately by telephone and when necessary followed up with annotated photographs and/or photograph derived sketches. A textual summary of activity derived from any photographic interpretation would subsequently be included in the Corps INTSUM, at the latest the day after the photograph was taken. Corps Topographical Sections, although not empowered to produce formal background maps, this role remained at Army level, were responsible for the production of ‘hasty’ maps and sketches at short notice to support on-going Corps operations. The nature of the work, which included producing trench map overlays showing the latest changes and Barrage and Counter Battery overlay maps, resulted in these sections taking a more considered view of the aerial photographs taken. The results of their photographic interpretation were incorporated on the maps and sketches they produced. In addition textual summaries of activity derived from any photographic interpretation that complemented the BIS reporting would be included in the Corps INTSUM up to two to three days after the photographs were taken. Immediate ‘first phase’ reporting was being carried out by the BIS’s, whereas considered ‘second phase’ reporting was being conducted by the Corps Topographical Sections. The birth of these two sections streamlined aerial photography’s TCPED process making it both coherent and efficient, thus enabling it to support both superior and subordinate units. The positive impact of these two sections serves to support and reinforce the view presented by Andy Simpson that:

‘From being a post box in 1914, the corps was becoming a vital clearing house for information by late 1916. Andy Simpson, Directing Operations (Brinscombe, Spellmount, 2006) p. 53.

Expansion of Photographic Interpretation Expertise

With the increase in demand for, and the wider distribution of, aerial photography came a corresponding need for more specialist intelligence staff in subordinate units to carry out the photographic interpretation. From late 1916 Intelligence Corps officers, trained to interpret aerial photographs, began to be attached to Divisional Intelligence sections (F M Cutlack, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914–1918, Volume VIII – The Australian Flying Corps in the Western and Eastern Theatres of War, 1914–1918 (11th edition, 1941), pp. 206 - 207.). These officers were supported by an office staff of an aeroplane photo man, three draughtsmen and two clerks (Hahn, The Intelligence Service within the Canadian Corps 1914-1918. pp.113 & 119.). By the end of 1916 photographic interpretation skills had permeated down to divisional level. Structured training was required to push the skills down further.

Photographic Interpretation Guides

The first photographic interpretation practitioners, who included Romer (First Army’s Maps and Printing Section early 1915), Lloyd (First Corps Intelligence Officer 1915) and Goldsmith (Third Army’s Compilation Section 1916), all learnt their skills ‘on the job’. Photographic interpretation was so new that no training formal or informal was available. Slowly a body of experience was built up and was translated into guides and training courses. The first guides developed in an ad-hoc fashion and were genuine attempts by the early pioneers to share their new found knowledge. As already mentioned, Lloyd probably produced the first British photographic interpretation manual that was published in November 1916. Although early in July 1916 Moore-Brabazon, dissatisfied with the use being made of the RFC photography by the BEF’s intelligence elements, produced and circulated six copies of a photographic interpretation guide called Photographs taken by the Royal Flying Corps: (Moore-Brabazon, The Brabazon Story, (London, William Heinemann Ltd, 1956), p.96. Medmenham Collection DFG 1471, J.T.C. Moore-Brabazon, Letter to Squadron Leader Mayle, School of Photography RAF, 25 November 1959.). The covering note to the guide stated:

‘These photographs taken by the R.F.C. are put together in book form, in the hope that they may be of use in furthering the closer study of aerial photographs as an aid to reconnaissance.

I am indebted to the 3rd Brigade for most of the Photographs, and to Lieut St B Goldsmith of the 3rd Field Survey Company in including his observations of points of interest in them. J.T.C. Moore-Brabazon, Major R.F.C., R.F.C. G.H.Q., 8/9/16’. (Copy owned by Mr Barry Jobling)

In early 1917 Rory Macleod, who had been the liaison officer between Fourth Brigade RFC and Fourth Army’s Counter Battery Intelligence Staff in 1916, produced a book on the interpretation of aerial photographs for Fourth Army’s Artillery School. (Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers. p. 195.). By March 1917 the Intelligence Staff at GHQ had taken ownership of the photographic interpretation manuals and had issued S.S. 550 Notes on the Interpretation of Aeroplane Photographs which was distributed down to Battalion, Machine Gun Company and Trench Mortar Battery level (Finnegan, Shooting the Front. p.150.). This manual was updated in February 1918 S.S. 631 Notes on the Interpretation of Aeroplane Photographs (The National Archives, Notes on the Interpretation of Aeroplane Photographs, AIR 10/320.).

Photographic Interpretation Training

Photographic interpretation training developed in parallel with the interpretation guides. From early 1915, the RE’s were being trained to use aerial photography to support cartography. Also during 1915, Lloyd probably provided the first photographic intelligence related training classes, although they were arguably more capability awareness lectures rather than specialist practitioner training. Not until late 1916 was photographic interpretation incorporated into the syllabus of the 10 week Intelligence Corps Officer training course run in London near Wellington Barracks (Anthony Clayton, Forearmed – A History of the Intelligence Corps, (London, Brassey’s, 1993). p. 54.). By 1918 the photographic interpretation element of the Intelligence Corps Officer training course had matured significantly and focused on the uses of aeroplane photographs within intelligence sections at Division, Corps, and Army level. Exercises on the course required students, using aerial photographs, to make maps to plot onto and record information on machine-gun emplacements, artillery batteries, trench-mortars, and airfields, in a way that replicated what the BIO’s were doing in the field (Photogrammetric Engineering & Remote Sensing Vol. 74, No. 1, January 2008, pp. 81-82). For most of 1916 therefore photographic interpretation skills continued to be learnt on the job. As Francis Law (IXth Corps artillery intelligence officer) stated:

‘At first I found interpretation of aeial photographs difficult but did better with practice.’. Law, A Man at Arms. p. 74.

From late 1916 the newly appointed Intelligence Corps officers at both Division and the BIS’s had either been trained at the Intelligence Corps training school in London or in the case of reassigned officers, had attended the newly established eight day course on aerial photography run at Army level in France. Whenever possible post training familiarisation visits were provided to intelligence officers prior to them taking up their posts:

‘Saturday 24 February 1917 - Captains Bruce G.S.O. 3 of the 36th Division and one Barker who is Intelligence Officer to No 46 Squadron have been sent to spend the day with me as the culminating treat after an 8 day course of aerial photography.’. Hughes, ‘Diary’ of T McK Hughes.

Evolution of Photographic Interpretation Awareness Training

Following the formal establishment of the photographic interpretation practitioner training in late 1916, 1917 witnessed the formalisation of awareness training. By June 1917 the following courses, all of which contained aerial photography in their syllabus, were advertised in S.S. 152 Instructions for the training of the British Armies in France (Provisional) (S.S. 152, Instructions for the training of the British Armies in France (Provisional), (HMSO June 1917).):

* The Army Infantry School, training Company Commanders, Company Sergeant Majors and Sergeants.

* The Army Scouting, Observation and Sniping School training officers intended to become Brigade or Battalion Intelligence Officers.

* The Army Artillery School training Artillery Officers.

* Corps Infantry School training Platoon Commanders and Platoon Sergeants.

The success of the awareness training is evident in an anecdote provided by a British company commander. In 1917 C. J. Lambert with his Company of Royal Scots were occupying a sector of trenches near the Sencee River. Their lives were being made miserable by a German Mortar which defied all attempts to pinpoint its location using the routine aerial photographs available as it was too well hidden. In a further attempt to locate the mortar Lambert requested a dawn photograph in the hope that any tracks made by the mortar crew in the grass moistened by the early morning dew would reveal the mortar’s precise location. In his own words Lambert describes the result:

‘In due course I was handed a composite photograph which told me everything I wanted to know. It was a poor day for the trench mortar crew, . . . for the mortar ceased to trouble us following a call to our supporting artillery.’. Medmenham Collection DFG 3410, Letter Lambert to Babingdon-Smith, 23 Dec 1957.

A key success that justified the organisational changes and the efforts being put into photographic interpretation training came during Third Ypres. Haig in his diary entry for the 28 August 1917 recorded:

‘Trenchard reported on the work of the Flying Corps. Our photographs now show distinctly the ‘shell holes’ which the Enemy has formed turned into a position. The paths made by men walking in rear of those occupied, first caught our attention. After a most careful examination of the photo, it would seem that system of defence was exactly on the lines directed in General Sixt von Armin’s pamphlet on ‘The Construction of Defensive Positions’ . . .’. Gary Sheffield and John Bourne eds, Douglas Haig War Diaries and Letters1914-1918, (London, Phoenix, 2006) p. 320.

The II ANZAC Corps INTSUMS had begun to highlight the use of shell holes in late July:

‘. . . tracks lead to the river bank just north of the village, C 11 a 55.50 opposite the farms on the western bank; these run to shell holes or places where machine guns could be fired from (42B 1693).’ Australian War Memorial, II ANZAC INTELLIGENCE SUMMARY to 6 p.m. 23rd July 1917, AWM4/1/33/15 Part 2.

Following this discovery of what was the German defence-in-depth system the weight of British artillery barrages was switched onto the shell holes. This change increased German casualties and dislocated their defensive system.

By the end of 1917 personnel with a remit to carry out photographic interpretation were located on the Intelligence Staff at Infantry Brigade and Battalion level. The Brigade and Battalion Intelligence officers would have attended the ‘The Army Scouting, Observation and Sniping School’ whilst the support staff were trained at Division or Corps level by an aerial photograph expert. During early 1918 Hughes (BIO 53 Squadron) conducted a number of these training sessions:

‘Thursday 17 January 1918 - I went to Corps to give my famous lantern lecture to a new group of would be Intelligence Officers from the trenches. Hughes, ‘Diary’ of T McK Hughes.

The BEF of 1918 had succeeded in placing photographic interpretation personnel, trained to the appropriate standard, in intelligence sections at all levels.

Figure 13. Intelligence and Photographic Organisation c1917.

The Uses for Aerial Photography

Foundation Material

During the retreat from Mons in 1914 the scale of the movement involved meant that there was no requirement for detailed large scale maps to support the BEF. The first demand for large scale detailed mapping came after the battle of the Aisne as the front line began to stabilise. At this time with no trained surveyors available the BEF had to make do with the inaccurate 1:80,000 French mapping enlarged and redrawn at the Ordnance Survey Office Southampton. These enlargements were completely unsatisfactory, reproducing and magnifying the errors on the original that introduced gross positional errors. What was needed was a new field survey of the BEF operational area. In November 1914 two trained surveyors arrived in France as part of the First Ranging Section RE’s. These two surveyors were tasked with completing a survey that would enable a more accurate map to be produced in as short a time as possible. Their field work started on the 25 January 1915 and by the 28 February all the field sheets were passed to the Ordnance Survey for reproduction. The resulting 1:20,000 scale map was a vast improvement on the previous 1:80,000 enlargement (Winterbotham, Survey on the Western Front. pp. 6-7.). Its comparative accuracy improved the targeting accuracy of the British artillery and led to demands for accurate mapping of the German held territory.

As mentioned previously, the responsibility for mapping the German-held territory rested with the GS Intelligence. However, the success of the Neuve Chapelle battle map ultimately led to the formation of Army Topographical Sections that became responsible for all map production in their Army’s area of interest. By the end of 1915 a newly created series of 1:10,000 base map sheets overprinted with the tactical detail of the German defensive positions had been produced. Aerial photography was the primary source used to derive both the topographical and intelligence detail displayed on the mapping.

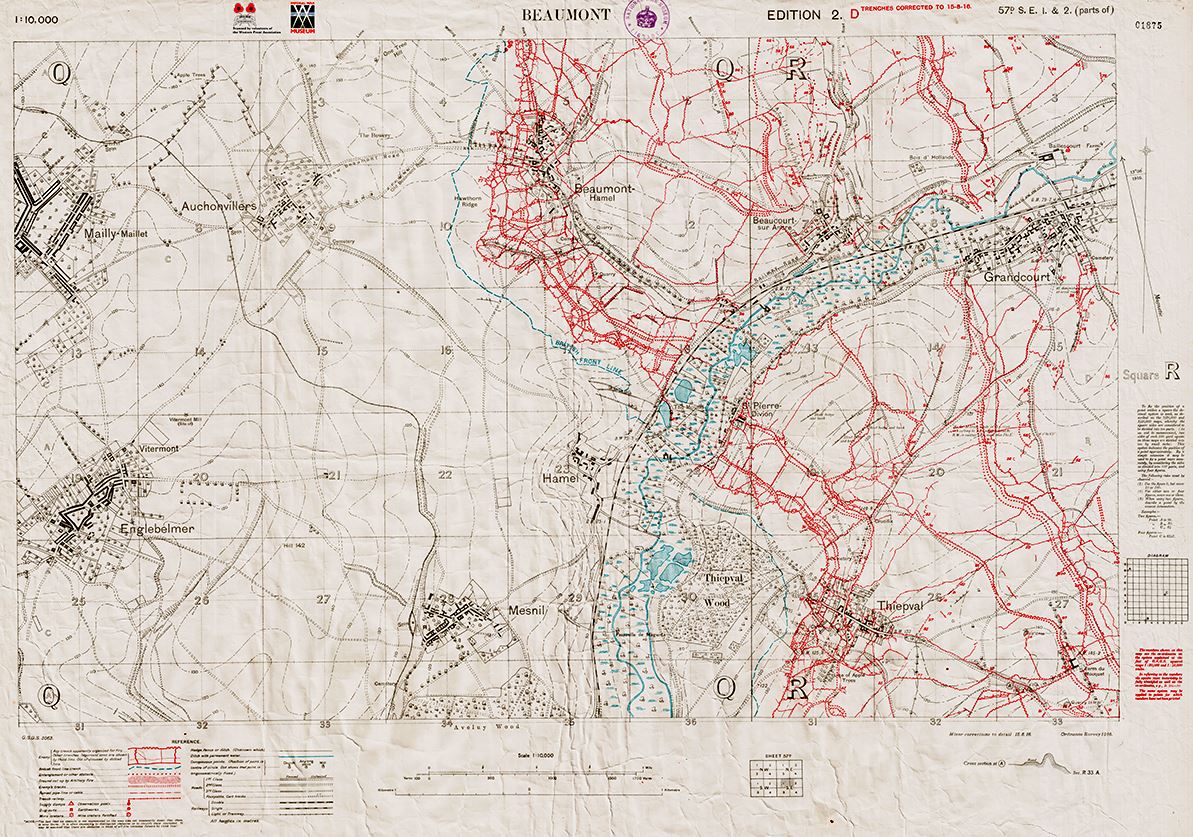

Figure 14. 1:10,000 scale trench map dated 15.8.16 (source: WFA TrenchMapper).

Illustrated above (Figure 14) is a standard British 1:10,000 scale trench map overprinted in red with the German defensive positions. From 1916 maps of this type would be found adorning the walls in HQ’s and Intelligence sections throughout the BEF. The BEF now had a coherent framework on which to build a COP. The real challenge was to maintain the pictures currency to ensure a high level of situational awareness at all levels of the BEF.

Situation Awareness

During 1915, map production and map revision time, from the start of drawing to receipt of the map ready for use, took about two weeks. By 1916 the pressure of work at the Ordnance Survey had extended the production timescale out to four weeks (Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers. p. 87.). As a consequence by the time a map was received at the front it was already out of date. This issue of currency was appreciated as early as the battle of Loos in 1915 when copies of aerial photographs were circulated so that staff and regimental officers could make hand written amendments to their maps (Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers. p. 108.). During Loos, Romer (First Army Maps and Printing Section 1915) had his section working through the night producing and printing special map sheets showing the new detail derived from that day’s aerial photographs; these sheets were sent by dispatch rider to the affected units (Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers. p. 110.).

Aerial Photography Limitations

Aerial photography was proving central to maintaining situation awareness, although it was not a panacea but had marked limitations which included; a lack of persistence, weather dependency, and a slow (relatively) response time. Aerial photography lacked the persistence of visual reconnaissance; it was after all ‘a snap shot in time’. But to counter this it did provide a permanent record not prone to memory failings, in addition the ability to revisit an area of interest through a collection of photographs, the HOC, gathered over time proved invaluable for change detection. Weather played a key role in the successful collection of aerial photography. The poor weather at the end of Third Ypres is probably one of the reasons why II ANZAC Corps’ photograph availability was so low during the period (Figure 15). Response time proved problematic during the war. Much has been made of the ‘speed tests’ demonstrated during the Somme where from aircraft landing to processed prints arriving at Headquarters took as little as 30 minutes (Finnegan, Shooting the Front. p. 75.). It should be noted that photograph processing, printing and delivery was not the whole picture. Including tasking and flying time, plus time for interpretation and product dissemination; any response would have be extended to several hours or even longer as illustrated by the Lambert (Royal Scots Company Commander 1917) anecdote above (part 3). In the static warfare of the Western Front this was less of an issue, which was tempered further through regular pre-planned photograph collection. The intent, weather permitting was to photograph the German trench system up to a depth of 3,000 yards every five days, and the counter-battery area every 10 days (B.E. Sutton, ‘Some Aspects of the Work of the Royal Air Force with the B.E.F. in 1918’, RUSI Journal, 67 (1922:Feb./Nov). p. 339.). During operations this tempo would obviously change. At Messines in 1917, aerial photographs of the German defences were taken every day during the preliminary bombardment, and the known artillery positions every two days (Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers. p. 304.). This meant that even outside of operations a regular supply of photographs was available and distributed.

Access to Aerial Photography

As has been outlined, access to aerial photography and intelligence derived from it expanded down through the echelons of the BEF throughout the war. Figure 15 illustrates the availability of aerial photography to the Australian forces in France from April 1916 to October 1918 based on a review of I and II ANZAC Corps and the Australian Corps daily INTSUMS over the period. Bearing in mind that the Dominion forces were fully integrated and supported within the BEF, it is probably fair to assume that the availability illustrated is representative for all the Corps in the BEF from 1916.

Figure 15. Aerial Photograph availability derived from I and II ANZAC Corps and the Australian Corps daily Intelligence Summaries.

The Distribution of Photographic Prints

The distribution of photographic prints came in three forms, raw, annotated or as part of a specialist product for example a mosaic or stereo pair of photographs. During 1915, with the RFC Wing photographic sections managing the distribution of prints, the majority went out raw with the recipients expected to carry out their own interpretation and build their own specialist products. In 1916, following the establishment of squadron photographic sections, an initial proof distribution to the demanding unit/s was handled by the squadron. A full distribution would be made by the RFC Wing following the transfer of the negatives. Again, the majority of the prints went out raw. With aerial photographs now being seen as a direct source of intelligence by the artillery and the infantry, the demand for prints and specialist products soured. While the print distribution process struggled to cope with the new demand the print production process failed; resulting in frequent delays in the delivery of prints to the subordinate units. The BEF’s response was twofold, to fill the gap with text reporting and find an organisation that could carry out the necessary bulk printing. The qualitative improvement in the text reporting noted previously in the First ANZAC Corps INTSUMS during 1916 illustrates the success of the text reporting approach. The text reporting was structured around the map grid referencing system to facilitate hand written updating of the available mapping:

‘(A). A well defined track evidently considerably used, leading from the communication trench at R.35.a.6.2 ½ . and proceeding in a N.E. direction to R.35.b.4 ¼ .8. where it meets the new trench dug to protect COURCELETTE from the South.’. (Australian War Memorial, FIRST ANZAC CORPS INTELLIGENCE SUMMARY to 6 p.m. on 31st July to 6 p.m. on 1st August ‘17, AWM4/1/30/7 Part 1.)

Text reporting also had an unforeseen corollary; not only did it widen the availability of photograph derived intelligence but it also increased the demand for it. From October 1916 the Army Printing and Stationary Service (AP&SS) had set up a section in Amiens that could produce 5,000 prints a day. Initially only print production runs greater the 100 were authorised. By the end of the Somme each army had its own AP&SS section bulk reproducing prints and specialist products (Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers. p. 227.). With the printing problem solved by the end of 1916, a corresponding reduction in the text report could have been expected. This was not the case, text reporting via the updated map was able to reach a wider audience than the distributed print.

The establishment of the BIS’s in 1917 changed the print distribution dynamics and made the RFC squadron the coordinating unit (Figure 16). With a photographic interpretation function now co-located at the RFC squadron, the form of the distribution changed. When a photograph reconnaissance aircraft landed, proof copies were printed as soon as the photographic plates were developed. These copies would be annotated, by the BIO or his staff, showing any changes in the German defences disclosed by comparison with previous HOC photographs and then distributed as a priority, within 30 minutes, to the GS Intelligence officers at Army HQ, Corps HQ and Heavy Artillery, and Division HQ and Artillery.

Figure 16. Corps Squadron – Aerial Photograph Tasking and Distribution from 1917.

A second issue that expanded the distribution down to Company level when required followed approximately six hours later. (Hahn, The Intelligence Service within the Canadian Corps 1914-1918. pp. 118-119.). Figure 17 illustrates a BIS annotated proof vertical photograph.

Figure 17. Vertical annotated proof print. (Source: Mapping the Front; The Western Front Association Ypres – British Mapping 1914 – 1918 DVD )

All down the distribution chain, the photographs would on arrival be re-examined and used from the perspective of the receiving unit. From 1917 on, a soldier at platoon level could expect to carry out trench raid mission rehearsals behind the British line in an exact replica, derived from aerial photography, of the German trench system he was going to raid. Although preparations did not always go smoothly:

‘Thursday 15 February 1917 - Considerable panic over photographs. Everyone who is going to have a raid naturally wants photographs of the trenches they propose to enter, but as a rule they let us know about a day before the raid when it is probably quite cloudy. (Hughes, ‘Diary’of T McK Hughes IWM).

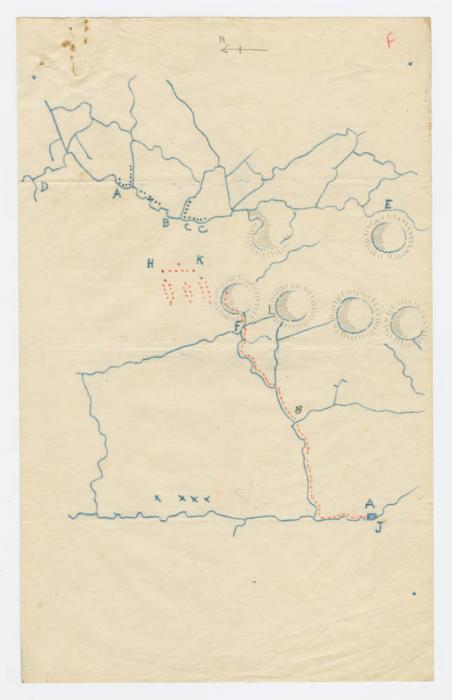

The photographs would also have been used by the officer commanding the raid to generate a sketch map that could be used by the other members of the raiding party. Figure 18 illustrates an aerial photograph derived sketch map used in the Roclincourt area by members of the 2/14th Battalion London Regiment who conducted a trench raid on 19 September 1916.

Figure 18. Aerial photograph derived sketch map. "The Body Snatchers": Trench Raid at Roclincourt https://digitalcollections.mcmaster.ca/pw20c/case-study/body-snatchers-trench-raid-roclincourt

Battle rehearsal also benefited; prior to their assault on Vimy Ridge in 1917 the Canadians built a scale model of their assault area based on aerial photographs (Figure 19). Whole divisions were taken to view the model as part of their battle training and preparation.

‘In an area well behind the lines, a large model of the Ridge, showing every phase of the German defence positions as gleaned from aerial photographs was laid out. In turns our battalions were taken back to this model, where, on a simulated pattern, they were shown exactly what they had to do and where they had to go on the day of the assault.’ (Bloody April p 119-120)

Figure 19. Vimy Ridge trench model 1917. (Source: Wikipedia)

Amiens in 1918 saw a proliferation in aerial photographs being made available at company level for study before the attack. In addition the following products and photographs were issued to the attacking troops:

(a) A Mosaic of each Divisional front, squared and contoured and freely annotated, for distribution down to N.C.O’s.

(b) Oblique Photographs of each Divisional front, for distribution to all officers. Australian Corps Battle Instructions for 8th August 1918, quoted in: Chasseaud, Artillery’s Astrologers. p. 447.

Ultimately situational awareness was facilitated at every level through the availability and local exploitation of aerial photography.

Actionable Intelligence

The trench map and the processes used to maintain the map’s intelligence currency provided a framework onto which could be fused intelligence from other sources. This section will explore the evolution of counter-battery artillery intelligence fusion, a classic example of the operational/intelligence interface where aerial photography fulfilled a crucial role in providing and/or corroborating intelligence that could then be acted upon.

The Artillery Counter Battery Role