Way of Revelation (1921) by Wilfred Ewart

- Home

- World War I Book Reviews

- Way of Revelation (1921) by Wilfred Ewart

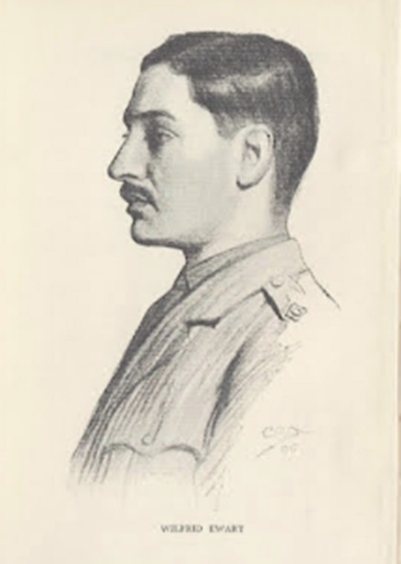

Wilfred Herbert as portrayed in Graham Stephen's 'The Life and Last Words of Wilfred Ewart' (1924)

At the time of his death, the 30 year old Wilfred Ewart was a successful journalist and author who had given five years of his life to the Great War. Composed in notepads and published as reports under various names during the war his fictionalised account 'Way of Revelation. A Novel of Five Years' published in 1921 was an immediate success. His novel used a combination of his experience as a wealthy upper class young man socialising in Belgravia and Mayfair before the war, and as a subaltern in the Scots Guards 1915-1918. 'Way of Revelation' was written in 1919/1920 and published the following year.

Suffering from mental illness, a product of the war on his febrile mind, he was only just starting to give his career some kind of orientation in 1922 when he took up a suggestion by his close friend Stephen Graham to join him and his wife in New Mexico for a break. Ewart had a trunk of notes and documents required to write a history of the Scots Guards in the Great War sent out to him. At the time he was thinking that his career would be more towards journalism than writing more fiction. Just as George Orwell later researched and wrote ‘The Road to Wigan Pier’ in the 1930s having 'been there', in situ, living and breathing it, so Ewart had spent 1920 in Ireland researching and writing about the people, the politics and their circumstances. This was when he was at his best and felt most comfortable and we know that his best writing in 'Way of Revelation' is a document to events. Having made it to New Mexico he was offered the chance to go to Hollywood which had optioned his novel. This and his admiration for the work of Thomas Hardy meant that fiction still had its attractions.

As already mentioned, ‘Way of Revelation’ was closely based on a series of pieces Ewart had written under different names for different publications during the war. For example, he described Ypres for a piece in the Spectator as “The very earth itself, so maimed and scarred, spoke of war’s eternal mystery, of God’s anger and tribulation, of man’s agony and bloody sweat.” (Graham, 1924 p.43) Or the piece written for G.A.B Dewar on the little known about twenty minute Christmas Truce of 25 December 1915 which found soldiers of the Scots Guards and 119th Saxon Regiment “leaping back and forth over a shallow stream that divided them as a friendly game, like schoolboys on a common playground”. (Graham, 1924 p.36)

After the war, according to Graham, Ewart was “persuaded to write a fictional account under his name” in 1919, fiction, rather than non-fiction, to avoid the risk of libelling his fellow officers and London friends, but also allowing him to say "whatever he likes". (Graham, 1924 p.14) In ‘Way of Revelation’, the thinly described Ewart, now the young Sir Adrian Charles Knoyle, is portrayed as a budding artist, sketch pad in hand, rather than Ewart, the journalist, notepad at the ready, which was how Ewart who rose through the ranks from 2nd.Lieut. to Captain, was remembered.

As a boy his character revealed itself at St. Aubyns School, a boys’ boarding prep-school in Rottingdean, East Sussex where he ‘grew introverted and acutely sensitive to criticism’. He was a loner, focused when he wished to be and bright, but also impetuous and emotional. Mental ill health ran in the family - his mother was mentally unwell. Today, a boy with Wilfred Ewart's traits and behaviours might be identified as ‘high achieving autistic’, ‘on the spectrum’ or perhaps ‘ADHD’.What is more, he was blind in one eye, also a hereditary genetic disorder and had poor eyesight in the other, and was sickly. He made only a few close friends at St. Aubyns, such as George Wyndham who was killed on 24 March 1915 -having had his periscope shattered by a shot Wyndham leapt up to shoot back and took a bullet through the head. (Graham, 1924 p.30) Far from the cliché of distant late Victorian upper-middle class parents, his father, knowing his wife’s unstable mental health, was sensitive to his son’s plight. Rather than having Wilfred endure Eton where he was to go after St.Aubyn's, instead he had the 13 year old Wilfred sent to Bournemouth to receive a short secondary education from a tutor. Two years later, age 15, Wilfred was packed off to Cambridgeshire to learn about farming.

Ewart wrote about what he observed and did. His literary skill, eye for detail and confidence developed by writing about farming and the Cambridgeshire countryside in general, and poultry and raising chickens in particular. He earned good money, co-authoring a top-seller on raising chickens and contributing regularly to a variety of magazines.

At this time, Wilfred developed an enduring passion for the works of Thomas Hardy which he read voraciously; he reportedly kept a copy of 'Tess' stuffed into a jacket pocket while in France. He later troubled the reclusive Thomas Hardy with letters, got no reply, and eventually turned up at the great man’s home having travelled to Dorset by motorbike determined to meet his idol. When ‘Way of Revelation’ was published he sent Hardy a copy. Hugh Cecil, who over ten years researched and wrote the highly acclaimed 'The Flower of Battle. British Fiction Writers of the First World War' (Cecil, 1995), a study of some of the fiction that emerged from the Great War is critical, suggesting that Ewart had a tendency to ‘slip into cliché and melodrama’ (Cecil, 1995. p.120). On the contrary, despite or because of his upper class background and his knowledge of Thomas Hardy, he was honing his storytelling skill though likening 'Way of Revelation' to Tolstoy's 'War and Peace' may be stretching it a bit.

In his twenties, early in the new century and before the war, according to Stephen Graham, Ewart’s "life was just one round of pleasure". (Graham, 1924 p.10) He attended multiple balls off Green Park (Belgravia, Mayfair, Piccadilly) often moving on from one party to another through the night and staying up 'til dawn to breakfast in Covent Garden - still in tails and white tie. Ewart had an allowance and also earned additional money from his journalism which allowed him to enjoy a lifestyle becoming of an upper class Briton who still lived at home and would acquaint the top restaurants and private clubs. Whilst he moved in the highest social circles in London (his mother came from an aristocratic family), his temperament meant that Wilfred appeared somewhat standoffish with those he did not know. He kept notes assiduously. The habit, long established, of keeping a notebook to hand explains how he could recall for later use vivid descriptions of people and landscapes, writing about the Wiltshire Downs, the Thames Valley and the Wash across the seasons for publications such as Country Life (launched in 1897) and The Sunday Times or noting conversations, the trivia as well as the important. Graham described Ewart as ‘an onlooker in all society life and to its fringes, a pocket notebook to hand.’ (Graham, 1924, p.107) Ewart described society balls and the relationships between generations and between the young all on the cusp of change with aplomb.

If you are familiar with French and the struggles we British have with the correct use of ‘vous’ for someone with whom you are unfamiliar or ‘tu’ for someone you know well and children, then this in the 1910s would apply to the upper classes in London and whether you referred to someone by their surname or Christian name. This is expressed well in ‘Way of Revelation’ as two young people, he is twenty, she is eighteen, slip from referring to each other by surname and then Christian name - along with a little hand holding and a stolen kiss. It is this, and more, that convinces you that Ewart is providing a credible portrayal of the people of this class, the places and the time. What is more, with the balls across Mayfair and Belgravia before the war and the Victory Ball in 1919, and the muted, changing social scenes in London and Paris in between, you get a vivid idea of how people and behaviours were changing making ‘Way of Revelation’ as much a social history as a military history. Though here too, when reading Ewart’s factual accounts of the 'Scots Guards 1915-1919' (Ewart, 2001) and compared them to his supposedly fictionalised accounts for ‘Way of Revelation’ you find his description of events the same, almost word for the word; if anything the ‘fictionalised’ accounts are more vivid, fluidly expressed and believable - only the names of those around him are changed.

An indication of how Ewart was more a political commentator than a writer of fiction is revealed in the views he puts into the protagonist’s mind on the threat of war. According to Cecil (1995, p.127) Ewart felt that Sir Edward Grey, the Liberal Foreign Secretary, had been right to strengthen his country's links with France and Russia, but wrong not to warn Germany explicitly that Britain would back up her two friends in the crisis of July 1914, for that would have scared the Germans into sense.

I disagree with Cecil’s view that the upper classes, ‘Britain's hereditary ruling class, the aristocracy’ were somehow compelled, more by the stick of the Parliament Act of 1911, than the carrot of adventure to enlist in their droves. (1995, p.127) That the ‘strongest incentives of caste pride and noblesse oblige’ were required ‘to show an example of courage and leadership’. Rather, I would take the view that the ‘public school system’ of education, from the best known public schools of Eton, Haileybury, Winchester and Harrow to the minor public schools of Eastbourne College, Sedbergh and Ampleforth were at their heart, institutions designed to deliver young men into the Army and Navy whether there was a war in Europe or not. There was after all India to run.

Ewart should not have been able to list: he was afterall blind in one eye and had poor eyesight in the other. But where there are connections, there is a way - as Rudyard Kipling got his son into the Irish Guards even though his son John had dreadful eyesight.

“‘What surprised me’, wrote a former private in the Guards many years afterwards, was that no physical standards appeared to be necessary to qualify for a commission in the Guards. The main qualifications seemed to be wealth and social position.” He encountered no problem, Cecil goes on to explain (Cecil, p.127), as Ewart’s first cousin was the Master of Ruthven, who commanded the First Battalion, the Scots Guards. He suggested that he should join his regiment, and the doctor examining him passed him fit for service, as requested. The same might be said of the diminutive Edward, Prince of Wales (a little under 5ft 6 inches) when he joined the Guards even though the height requirement was 6ft.

On 22 Feb 1915 Ewart went out to France

2nd. Lieut. Ewart took a troop ship from Folkestone to Honfleur and then a train that followed the coast through to Calais and on to Estiare. (He describes the scene, the landscape and troops, the locals - mostly women and children). Wilfred went into the line on 25 February 1915 when his battalion relieved the 1st Grenadiers. It was a depressing initiation. Sitting down behind the machine-gun emplacement on a small rise, he surveyed the scene from a safe vantage-point:

“I see a wide and shadowy country. The moon is rising out of the calm night. A little wind whines and whispers among the sandbags. I see dimly a land of poplars and small trees (dwarf oaks), orchards, and plentiful willows. I see flat fields and ditches and plentiful water, and red farms whose roofs are gone, stark skeletons in the moonlight. I see broad flat spaces and then a ridge, the ridge of Aubers. Only the German lines are hidden from sight.”

Ewart went ‘over the top’ on 11 March 1915 and was promptly shot through the leg; others were killed whilst he had received a 'Blight one' - the bullet had passed through the calf muscle of his left leg. This led to six months to recover back in England during which time he took the opportunity to use his notes to write numerous articles about his experiences of just a few weeks for a number of publications. It is these articles that later formed the basis for ‘Way of Revelation’ and the posthumously published ‘Scots Guards’ assembled from his articles by Stephen Graham.

Wilfred fell in love. Once more in London he was another young person ‘desperate to have a crush, someone to think of.’ Wilfred developed a crush on the young, beautiful and naive Dollie Rawson (on whom he based the character Lady Rosemary in ‘Way of Revelation’). His feelings and actions were not reciprocated. "Not a boy or a girl there but has had a 'flutter', some trifling affair de coeur, but cherishes some little one to whom the heart (for a while) returns." (Cecil, 1995, p.139) Ewart described London at the time in ‘a dance macabre, with the ‘boy girl’ parties decidedly more sexual, the younger girls deliberately frivolous, as if to deny the war and unchaperoned - the feeling being that the older generation wanted the young to enjoy themselves untethered given how unsure life had become.

Wilfred, having suffered rejection, a sensitive soul who took criticism and rejection badly, swore never to marry. He became celibate and unlike his fellow officers would have nothing to do with the "halatory of Paris". (Graham, p.57) He milked his feelings and in due course poured these into ‘Way of Revelation’ when the duplicitous ‘Rose’ maintains a male acquaintance, a consort if not a lover, while Wilfred’s persona Lord Adrian is away on the Western Front.

Ewart’s Commanding Officer was the 21 year old 5th Earl of Minto, Victor Gilbert Lasiston Garnet Elliot-Murray-Kynynmound (February 1891–1975). He was the model for Eric in ‘Way of Revelation’. Edmond Elliot was killed in action just as Eric is ‘killed off’ in ‘Way of Revelation’. (Graham, 1924 p.72)

Ewart’s approach when writing factually about events is succinct and descriptive. This for example on the 2nd Scots Guards in Boulon Wood 24 November 1917.

"During the morning of the 24th November the Germans twice attacked, and at the second attempt pressed back British troops in the north-eastern corner of the wood. An immediate counter-attack delivered by the 14th Battalion, Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders, the 15th Hussars, dismounted, and the remnants of the 119th Infantry Brigade (40th Division and 1st Cavalry Division), drove back the enemy in turn, and by noon the British line had been re-established."

When he turned this same passage into fiction, it became more vivid with colours, shapes and details, alive with noise, conservation and more dramatic with men putting their lives in jeopardy, making mistakes, letting others down, being heroic, or not, dying slowly, or not, getting back to their trench … or not.

Ewart return to France, served again, narrowly escaped death in Bourlon Wood, fell ill and spent some time back in England. He may have served for five years in the Army until he left in 1919, but he 'only' spent a little over two years on active service in France.

The Victory Ball of November 1918

Ewart was witness to the Victory Ball of November 1918. This despicably ill-judged flaunting of wealth at a time of national relief that the war was over showed 'society' at its worst, with young people, unchaperoned by their elders, drinking and taking drugs as they pleased. What might have become an annual event stopped to prevent further scandal.

Ewart used the Victory Ball as the climax to 'Way of Revelation' where his relationship with Rose returns to haunt him in the shape of a drug-addled young woman, far from the 18 year old he had fallen for before the outbreak of war. Just as he used an exact retelling of events on the Western Front for the stage where his characters could play out their loves and losses, so he takes a record of the scandalous events of the Victory Ball and weaves them into ‘Way of Revelation’.

Held on 27 November 1918 in the Royal Albert Hall, the popular young actress, Billie Carleton, who had been at the event, died the next day from an overdose of cocaine, and as a result the fashionable couturier, Reggie de Veulle, and other more disreputable figures, were imprisoned for drug-dealing. (Cecil, 1995. p.147)

After travelling to Ireland to write about the situation there, and then having settled down to write and complete ‘Way of Revelation’, Cecil explains (Cecil, 1995, p.150) how in April 1922 Ewart had a breakdown. He could not write. His fingers seemed paralysed. He rambled inconsequentially. He was close to tears. In due course accepted Stephen Graham's invitation to stay with him and recover in Santa Fé, New Mexico.

On New Year’s evening 1922, after attending a review of 1922 at Teatro Lírico and a late dinner at the Hotel Cosmos with his friends Stewart and Angela Graham, Wilfred Ewart retired to his hotel - the Hotel Isabel, Mexico City. (Graham, p.255)

Between 11:30 and shortly after midnight, having changed into a dressing gown and with celebrations involving fireworks and live rounds shot into the night sky, Wilfred stepped out onto his hotel balcony. A stray bullet hit Ewart in the eye and killed him instantly. Later that afternoon, alerted by the hotel maid who had knocked on the door several times and had seen that a light was on, the police broke into the room and found a corpse on the balcony in pyjamas and a dressing gown. A bullet had passed into Ewart’s brain through his eye. One newspaper featured a photograph of the corpse. According to Graham, the expression on the dead face was “puzzled and annoyed”. Ewart was buried in the English cemetery in Mexico City on 3 January 1923. After being obliterated by a motorway bypass, Ewart's bones, and those of hundreds of others, were moved to a nearby chapel.

You have to wonder, had he lived, whether Wilfred Ewart would have emulated or bettered the likes of Ernest Hemingway, Robert Graves, Ernst Junger, Erich Maria Remarque, Blaise Cendrars, Richard Aldington, Vera Brittain, V.M. Yeats, John Buchan, Frederick Manning or J.C. Sheridan. Would Wilfred Ewart have been attracted by writing for Hollywood, or found journalism more appealing?

Wilfred Herbert Gore Ewart from a painting by Miss Nora Cundell

(Wilfred Ewart 19 May 1892- 31 December 1922 / 1 January 1923)

Review by Jonathan Vernon

Second hand hardback copies of 'Way of Revelation' are readily available, as are more recent reprints in paperback.

References

Cecil, H. (1995) The Flower of Battle. British Fiction Writers of the First World War. London. Secker & Warburg.

Graham, S. (1924) The Life and Last Words of Wilfred Ewart. London & New York. G Putnams & Sons.

Ewart, W. (1924) Way of Revelation. A Novel of Five Years. Second Edition. March 1924. London. G Putnams & Sons.

Ewart, W (2001) Scots Guards on the Western Front, 1915-1918. Strong Oak Press. (First published 1934).

Further Links:

Wilfred Ewart : Remember on this Day 1 January 1923

Ernest Hemingway : A Farewell to Arms

Robert Graves : From Great War Poet to Good-bye to All of That

Ernst Junger : Storm of Steel

Frederick Manning : Her Privates We

Erich Maria Remarque : All Quiet on the Western Front

Blaise Cendrars : The Bloody Hand

Vera Brittain : A Testament to Youth

John Buchan : Mr Standfast